When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss art. When artists get together for dinner, they discuss money.

–Oscar Wilde

The dust jacket of Art of the Deal is a marketing deception. It attempts to glamorize an emerging air fair in the Gulf States by visually underscoring the fad and fashion of contemporary art. One might expect this book by Noah Horowitz, recently minted Courtauld Institute PhD and newly appointed Managing Director of The Armory Show, to be another exposé of the contemporary “art world.” But it offers none of the bombastic art market reportage that has become so familiar. Instead, Art of the Deal is a dense and erudite tome that offers a sober (and sobering) analysis of contemporary art market economics with the aim of bringing clarity and transparency to the market’s murkier reaches.

Noah Horowitz, Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market, Princeton University Press, 2011.

While critical analysis of and about operations and economics of the contemporary art market is a growing academic endeavor, the most visible and popular books are quasi-sociological, for example Sara Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World (Norton, 2008) and Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). What make these books so beguiling are their juicy “in the know” anecdotes of and about artists, collectors, auctioneers, dealers, and curators who have achieved celebrity status in the cozy corners of the global art world. Hyperbole is a familiar device in art market reportage, and books such as these provide a weird comfort in an increasingly uncertain trophy market.

Some excellent examples of recent books that investigate the symbolic and commercial polarities of the art market include Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art by Olav Velthuis (Princeton, 2007) and Isabelle Graw’s High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (Sternberg, 2009). The value of these works, missing from most MFA syllabuses, is enormous. They offer insight into the complexities and realities of the art business, a subject typically avoided in graduate degree programs, which seem to fear discouraging their art students with harsh, post-graduation financial realities.

Art of the Deal appears after the economic “reset” (to use a term popular in the private banking industry) following the global economic crisis of 2008 and ensuing doldrums in the art market, which many dealers and collectors had believed was immune to recessionary effects. Critically, the book examines the post-2008 art market via an objective, thorough assessment of art investment funds, few of which remain operational and even fewer of which are successful.

Horowitz offers a tight discussion of the evolution of the contemporary art economy, neatly distinguishing it from the “art world.” He goes well beyond Velthuis’s sociologically driven assessments of the symbolic and cultural. Horowitz restates the conceptual models of the art market posited by activist-artists Martha Rosler and Gregory Sholette, as well as Pierre Bourdieu, Nicolas Bourriaud, and William Grammp. This is difficult territory to navigate, owing not just to the intellectual complexities of theory, but also to the inherent cultural “sensitivities” of market participants to notions of art’s “mystic truths” (to borrow from Bruce Nauman).

Art of the Deal offers an erudite assessment of art market values and prices viewed specifically through the emerging markets for time-based media works (video) and experiential (post-conceptual installation and performance) art. Horowitz provides insightful, albeit narrow, histories of their development and marketability. He specifically addresses these media because they challenge traditional notions of art market content and structure and represent new entrants into a market heretofore eclipsed by painting. He raises the necessary and difficult questions of how one values, collects, and maintains these art forms after their purchase.

Video art’s slow entrance into the art canon in the late 1960s and early 1970s was fraught with technical difficulties and commercial road bumps. It was not until the 1980s that video became accepted by curators; in the 1990s video as an art form flourished because of technological improvements. Horowitz asserts that video’s extension into the market then became more robust, leading to commercial success for numerous, previously neglected artists. This assertion can easily be disputed by scanning the rosters of New York’s and Los Angeles’s market-leading galleries. Video’s place in the art-product hierarchy remains small, and its cost and value are even smaller, despite the relative ease of commoditizing and distributing it.

Horowitz’s discussion of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle is a cogent and illuminating example of a successful artist’s commercial strategy, which leverages the production of physical objects to finance, produce and ultimately sell his media works. The author describes how Barney entered the contemporary art market, the complexities of and relationships between his production costs and art “products,” and the challenges of valuing and collecting the work. Horowitz neatly describes the relationships between Barney’s films and his drawings, sculpture, books, and other related pre- and post-products of film production. Barney’s production allows the author to address “chicken or egg” questions about how an artist’s work and by-products fuel one another and, in turn, feed a brand-conscious art market.

Sylvie Fleury, Serie ELA 75/K (Plumpity…Plump), 2000. Gold-plated shopping cart, plexiglas handle with vinyl text, rotating pedestal (aluminum, mirror, motor); 44 7/8 X 39 3/8 X 39 3/8 inches. © Sylvie Fleury. Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich.

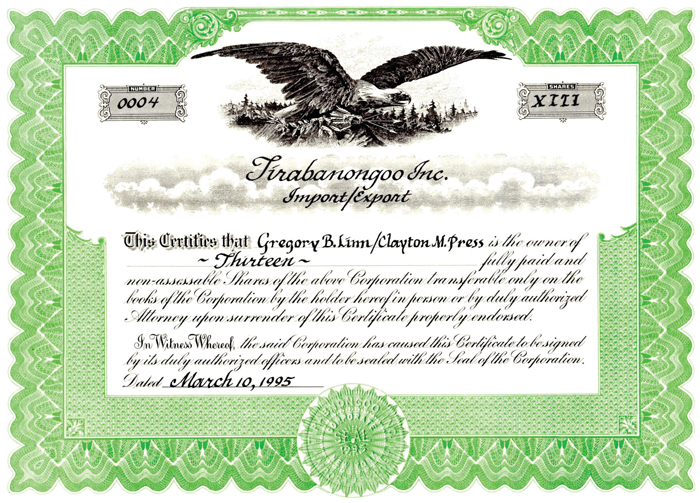

In his consideration of the market values for conceptual and experiential (largely installation) art, Horowitz falters somewhat. He considers at length the works of Rirkrit Tiravanija and Jason Rhoades through a scrim of Actor-Network Theory, which provokes challenging questions about the relationships between art experience and art product, the ephemeral and concrete, and value and price. Instead of speaking clearly to these economic concerns, Art of the Deal more effectively addresses the more symbolic value of the art lifestyle and experience, evidenced by museums, biennales, and art fairs, where the social-cultural theatrics of an event–“social marathons,” to use his term—can overshadow commerce. While Horowitz provides a sound history of the evolution of experiential art, his thesis would have been better served by looking closely (or more closely) at the products and prices of Marina Abromović, Joseph Beuys, Thomas Hirschhorn, Mike Kelley, and Paul McCarthy, to name just a few artists whose careers and production were slow to gain international market acceptance. (In fact, Art of the Deal often reads peculiarly U.S.-centric, given the book’s “global” emphasis.)

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Tirabanongoo Inc. Import/Export, 1995. Printed and embossed share certificate with hand calligraphy; No. 4, Shares XIII; 7 13/16 X 11 inches. © Rirkrit Tiravanija. Collection of Gregory Linn and Clayton Press, New Jersey.

The book’s penultimate chapter, “Art Investment Funds,” could almost be a stand-alone study of art investment portfolios, which emerged in the mid-2000s as vehicles to produce capital gains and income for wealthy investors using art and antiquities. It excels in comparing and contrasting this very small segment of the art market to hedge funds, private equities, and other alternative financial instruments and asset classes. Horowitz expertly assesses the relative roles and limited success of these funds compared to other art market channels. Moreover, his appendix of art investment funds is almost encyclopedic.

Horowitz (or Princeton University Press) has created a cumbersome read, familiar in dissertations turned into books. He states the problem, elucidates the approach, develops his thesis, populates it with arguments, restates the problem, but barely draws any conclusions. It is easy to get lost in the thicket. Moreover, the reader can come to the conclusion that there is no conclusion.

Horowitz’s strength lies in his thorough mining of the literature, which is demonstrated in sixty-five pages of tables and appendices, forty-eight pages of annotated footnotes, and a fourteen-page bibliography. These bibliographic resources are rich and invaluable for anyone seriously studying the history and economics of the art market, and this should include any MFA student. Most art graduate programs neglect–intentionally or not–the foundations, theoretics, and mechanics of art market economics and dynamics. Art of the Deal effectively and clearly reveals the “commercial truths” of three segments of the contemporary art market without hyperbole, which is refreshing.

Clayton Press is an arts advisor, curator, and management consultant, located near Princeton, New Jersey. Formerly adjunct faculty in the Art Market: Principles and Practices master’s degree program at FIT/SUNY, he is a frequent speaker about art economics and markets for financial service providers and a resource about art-related matters for such business publications such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Observer, and Alternative Latin Investor.