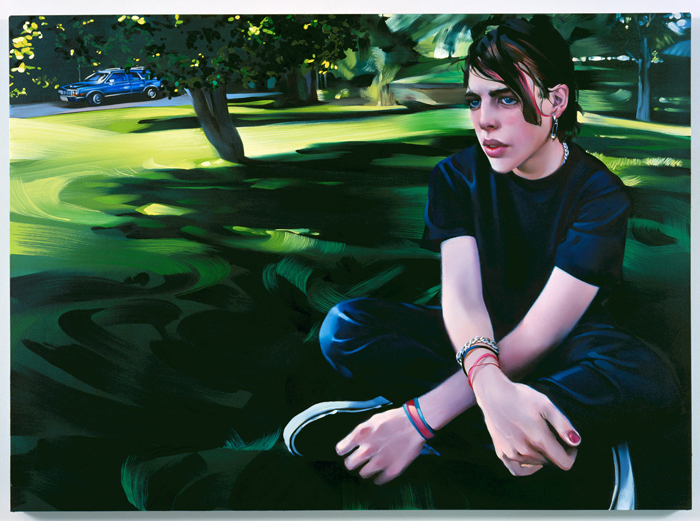

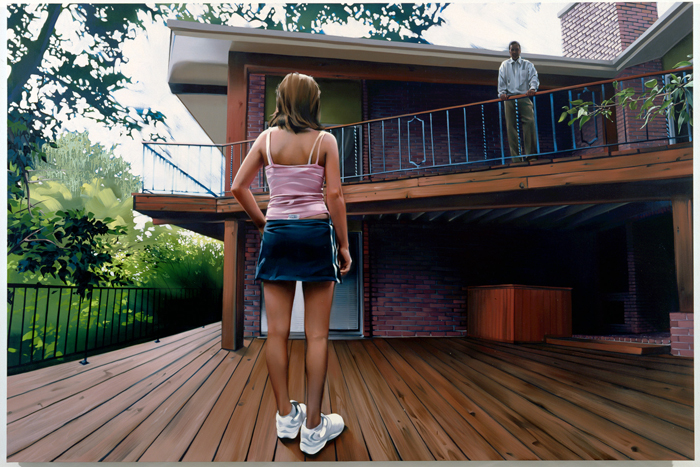

Rebecca Campbell is a woman of letters, with the ability to coolly transform mythological, folkloric, and poetic references into succulent visual allegories that are eminently personal and contemporary. This article considers allegories present in works from Crush as well as in works from some of Campbell’s previous exhibitions.1 Campbell’s fairytale series, for example touches upon the common desire to have a life more like a fairytale, a more dramatic existence. At the same time, her paintings put an ordinary face on mythic stories and characters. In Snow White (2000), for example, a decidedly average black woman stands in plain white underwear in front of a mirror. A woman lies nonchalantly in a bed, her small dog sitting by her side on a ruby red floor in Dorothy (2000). Lewis and Clark (2003), two dogs on a pink bedspread, are more likely to explore a suburban backyard than an uncharted Western frontier. In Snips and Snails and Puppy Dog Tails (2005), a disaffected teenager sits alone in a park, while a station wagon (Mother?) waits in the background. In other works, such as Salt Palace (2005), Campbell evokes her own past, using the title of the painting to draw upon the multifaceted history and metaphors of salt inspired by her home state of Utah.

Campbell’s paintings memorialize everyday moments that may seem dismissible but are ultimately definitive. In discussing her work, the artist invokes Barthes’s notions of punctum — the rupture, the slippage of a moment, image, or memory that trips you into a new place. “It is not the edges,” Campbell says, “but rather the middles where people flounder” that are most intriguing to her. “Nostalgia,” she continues, “is the cut that takes one to a new place, the cut that splits time. The moment of nostalgia is not specific, but seduces you into dealing with your own death, lures you into dissolving yourself.”2 To quote Barthes, “What pleasure wants is the site of a loss, the seam, the cut, the deflation, the dissolve which seizes the subject in the midst of bliss.”3 Campbell’s subjects are almost always figures, rendered in brilliant color with masterful, quintessentially painterly brushstrokes. The monumental size of her canvases connotes a deliberateness—the painting as an event—yet the imagery itself depicts quotidian subjects engaged in pedestrian activities: a woman in her evening bath, a young girl playing in the front yard, an adolescent sitting in a park, a young boy climbing a tree. Her paintings often take place in the impossibly long, lazy afternoons of a summer past. Not a summer that actually existed per se, but a summer as it is now constructed in memory. They have the oneiric quality of memories of your favorite house growing up, your first crush, or of the dream that for a moment makes you think that it is all going to be ok.

Her paintings embody many of the familiar art-world paradigms of opposition: photography and painting, realism and abstraction, public and private, monumental and incidental, documentary and narrative. They are simultaneously “a” and “not a.” This makes for a rich, complex viewing experience.

The volley between the uses of painting and photography in Campbell’s work, which has become increasingly photorealistic over time, alludes to the traditional perceptions of painting as a creative, constructed medium and photography as the objective arbiter of truth. The respective roles of painting and photography have changed considerably in recent years, particularly with the impact of digital media. The ease with which photographs can be manipulated (turned into paintings?) with the use of software has undermined the already shaky conception of the photograph as empirical truth. In making her paintings, Campbell first constructs a posed photograph, then alters it manually and digitally to alter perspective, color and scale. Finally, she paints these images in oil. She readily describes using lenses and photographic manipulation to create impossible viewpoints and compositions. The style of her brushstrokes also embodies this dichotomy, as she fluidly incorporates both photorealistic and intensely abstract and gestural characteristics. The notable inclusion of light as a key element of many of her compositions consciously draws attention to this common element of the two mediums. Campbell’s compositions are constructed “decisive moments,” to use the term that photographer Henri Cartier Bresson popularized in 1952 to describe the precise timing, gesture and composition that epitomize an event as captured by the camera.4 Campbell’s carefully conceived snapshots present the decisive moment not as physical, but as psychological. She posits the decisive moment as one that identifies the place of slippage or rupture, in which the normalcy of daily life seems beautiful and significant. Campbell appropriates cinematic devices through both perspective and sequencing. The viewer’s point of view seems to hover above the subjects as though looking down from heaven, or is slightly below the subjects, as though the viewer has just fallen slightly into the earth. It reminded me of reading Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones—a story narrated from a dead child’s point of view that similarly evokes nostalgia and the site-less places where memory resides. Large sweeping brushstrokes in some of the paintings give the illusion of a motion blur, as if the viewer was following the fast motion of a movie camera as it excitedly leads up to something, then suddenly stops, leaving parts of the world still in motion in the mind’s eye.

Campbell constructs filmic interplay between her paintings by showing the shot-reverse- shot depictions or by suggesting the passage of time between “scenes.” We see the back of a young woman in a romantic embrace in Bloom (2002). Hey Nineteen (2002) shows see the same composition as if seen from behind the young man that she is hugging; this time the shot is pulled back a little. The girl in this picture is perhaps the same one whose loss of innocence is mourned by a contemplative mother in Have You Seen The Most Beautiful Girl in the World (2005). The same, now familiar, girl’s back (clothed in pink tank top and white bra) is presented again in Salt Palace, as a teenager faces her father. A woman sits alone in a swimming pool in Radiate (2002), while another woman (perhaps in the house down the street) sits alone in a tub, like a conscious Ophelia, in Wallflower (2005). A bee floats in a jar in suspended animation (analogous to the act of extending a moment through the act of painting it) in Sugar House (2002) in the same way that the boy floats in the pool in Hover (2002). The boy in Hover is surrounded by gushing splatters of paint that at once evoke Francis Bacon, Lari Pitman, or even David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash (1967). The girl counting innocently, perhaps impatiently, a she waits in front of a birthday cake in Counting (2003) grows up to be the woman who counts (anniversaries? beers? holidays?) with a sparkler in her hand in Bang (2005). In viewing these paintings, one gets the sense that each moment is connected, whether in time, in our personal histories, or in our collective social experience.

As a whole, the body of work provides a collection of moments that can be read in any order to create allegories for the human conditions of wanting, waiting, hoping, asking, thinking. The paintings show us shifts in time — sometimes from one moment to the next, while other instances span years or entire psychological paradigms. While the individual paintings are narrative, the more interesting and complex narrative emerges through the relationship of two or more of the images. The corollaries from one painting to the next begin to reveal those things that are universally connected, those common elements that we all share. They are both moments that once actually existed and moments that Campbell imagined and constructed as hyperbolic summations of memory, imagination, and desire.

We tend to seek comfort in things that are beautiful, stories that are familiar, places and pictures that provide good memories. By poignantly evoking characteristics of nostalgia, Campbell asks us to examine where and how a sense of home is constructed. The word nostalgia comes from the Greek words nostos, or homecoming, and algos meaning pain or distress. Since 9/11, there seems to be renewed interest in the notion of “home.” With the buzzword “homeland” reiterated ad nauseum, it is interesting to observe that many young artists, Campbell included, are making work about missing home, or not being able to find or define home. Campbell’s paintings assure us that, as in The Wizard of Oz, home is in those everyday decisive moments. We just have to know where to look.

Micol Hebron finds home and beauty, but does not paint, in the edges of Los Angeles.