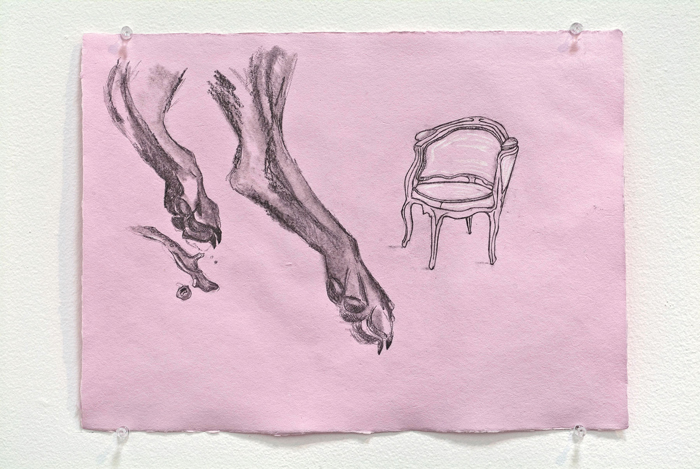

Nicole Cohen, French Connection 4, 2009. Graphite, pastel on paper; 11 ½ x 16 ½ ins. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

If you type the word “home” into an Internet search engine as I just did, you will garner more than four billion, eight hundred and thirty million hits.

This week, as I prepare for a large invasion of family, I find myself composing my home to an excruciatingly detailed turn. This is a kind of home work I learned from my mother, as she must have learned it from hers. The labor is this: clean and arrange the furniture, bedding, books, dishes—all the stuff of domestic comfort—for the pleasure of my visitors in an ideal tableau of welcome. My labor is only fleetingly productive, as I only see the house as a scene, a picture. (I am amazed at those who understand the home as a machine.) And my illusion is doomed as soon as a real body enters the room, with her own pleasures, ennui, and desires rampant, not to mention her stuff. But as I do this work of composition using all the concrete matter of my home, the imagined visitor is here, in this space, perhaps seeing this view while sitting in this chair, a kind of tableau vivant.

This home work carries a pleasure deeply familiar to me as far back as I can remember. I have found it playing “dress-up,” reading fiction, seeing palaces in tree houses and back yards, and imagining myself in a “little black dress,” or in the arms of —, and on and on. The distinct pleasure of shelter magazines—browsed in the banal delay of market checkout lines—is of the same order, as are catalogs, the viewing of period rooms in museums, and the visiting of “living museums” like Sturbridge village and Williamsburg. These last destinations are sanctified as historical preservation—a kind of domestic primping covered in academic laurels—made popular and approachable by historical reenactments and docent tours conducted in period costume, a kind of work that smacks distinctly of “dress up” and fantasy.

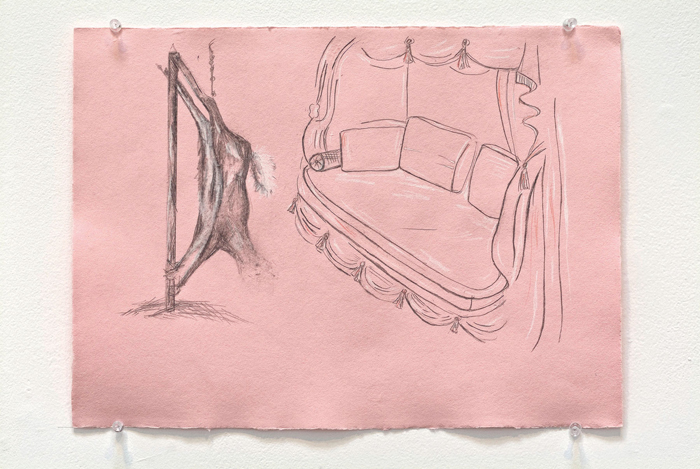

Nicole Cohen, French Connection 10, 2009. Graphite, pastel on paper; 11 ½ x 16 ½ ins. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

I think of all this when visiting Nicole Cohen’s show French Connection. In the gallery, a kind of space deliberately neither homey nor homely, Cohen stages a particular historical drama about home as a safe harbor, the anticipation of a longed for safe arrival, and the still palpable yearning of those who prepared for it and those who, even now, remember it. It is a labor of deep imagining, evident in both Cohen’s work on view here as well as that of the historical subject matter upon which she draws.

The show consists of four video loops and 16 drawings ruminating on the imagined arrival of Marie Antoinette, miraculously saved from the guillotine and living out a rusticated life in the Pennsylvania countryside in the 1790s. Cohen’s work defers the failure of the fantasy, as well as the grisly and very real historical outcome (as does Sofia Coppola’s cinematic treatment of Lady Antonia Fraser’s biography, both titled Marie Antoinette), to suspend us in an eternity of the home maker’s waiting, shot through with a sadness the seer Cassandra might have felt, as well as some wry laughter at the patent absurdity of the whole idea.

Nicole Cohen, French Connection 7, 2009. Graphite, pastel on paper; 11 ½ x 16 ½ ins. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

French Azilum is the site of a failed township on a bend of the Susquehanna river in what is now north central Pennsylvania. In the 1790s, french refugees from Europe and the island colony of Haiti, then known as Santo Domingo, converged on this spot to build a town. Now, this is a peculiar frontier idea. If you go out beyond the far edge of where anybody you know lives, claim a few thousand seemingly empty acres, lay out a town site with half acre plots and start a-building, then surely you will live happily ever after. U.S. geography is littered with these imaginative ventures, which are based on an assumption that the North American continent is an inexhaustible reserve of land in an Edenic state of nature, without human history or natural ecology to muddy up new purposes. The history evident in the name Susquehanna need not be of concern, for it adds just a soupçon of the picturesque to these tumbling, wooded hills, waiting patiently for the improving plow and the domesticating hearth. on this blank slate, anything is possible, even an asylum for a deposed and rescued Queen.

The insistent formal device in Cohen’s interrogation of this history, seen in both the drawings and videos she presents here, is pairing—sometimes confrontational, oppositional, or canceling, and sometimes relaying, complimentary, and revealing. In 16 pencil and pastel drawings on delicately colored paper, the binary at play in each work produces tension. After all, it is only on the level playing field of the sketchbook page (or the imagination) that you can have a bald confrontation between a Louis xv drawing room settee and a spitted deer, or the disembodied legs of a wolf and a rococo corner chair. I found myself thinking of Cohen sitting in her Berlin studio, herself a woman making a new home in a far away place, conjuring piecemeal the bits of incongruity that might have made up a frontier life for Marie Antoinette. Surely the Queen, playing pastoral “dress up” in Le Hameau, a farm folly constructed for her amusement in the gardens of Versailles, could never have been prepared for the crude frankness of life in frontier America.

The pastel paper fields of Cohen’s imaginings often map a chair, a stool, or a settee opposite a fire, an axe, or a spit, as if Marie Antoinette might alight, with proper 18th century decorum, to watch a flayed deer hide season in the sterilizing sun. Looking at these, I think of the organic inspiration for furniture design—legs, claw feet—as well as the crudeness of pragmatic camp lean-tos and roasting spits compared with the breathtaking sophistication of rococo and neoclassical furniture craftsmanship. The pastel shades of the paper—pinks, blues, and fawns—suggest the delicate feminine palette of a court lady’s wardrobe. These colors are emblematic of leisure not labor, like wearing a pristine white shirt on a farm. The white pastel over pencil and the fancifully bloated forms of the furniture in the renderings are reminiscent of book illustration. They remind this viewer of Kay Thompson’s famous Eloise books from the 1950s about a six-year-old girl living in that pastiche of a french chateau, the Plaza hotel—yet another American princess fantasy.

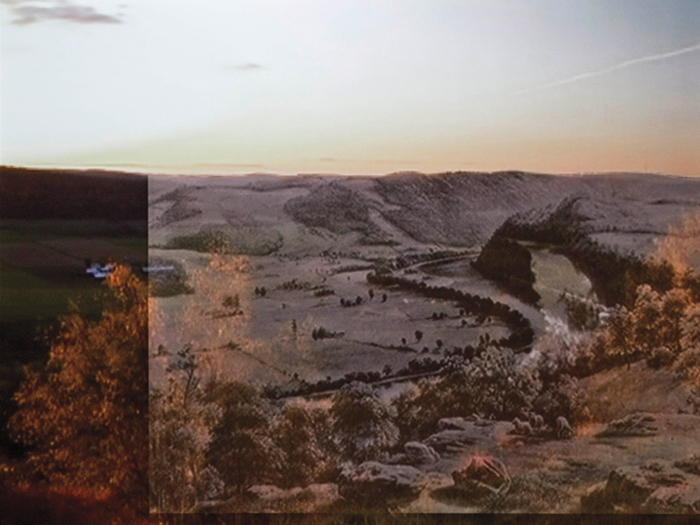

Nicole Cohen, Marie Antoinette’s Lookout, 2009. Video installation, 4:00, looped. Edition of 3, 2 Aps. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

In the videos the doubling appears as a double exposure—one scene pierced, interrupted, or simply obscured by another. They are austerely presented in a large, darkened gallery suffused with quiet music. elegant, melancholy John Fahey guitar plays a tune called Poor Boy a Long Ways from Home, which blends and alternates with Vladimir Ashkenazy’s rendition of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 8, known as the “Pathetique” for its mournful tonalities. Again, we find an odd couple, in a confrontation between the folk music of frontier necessity and the music of an extremely sophisticated European cultural system, the same system that produces both aristocratic patronage and the aristocrat.

Marie Antoinette’s Lookout (2009) shows a pastoral view of verdant rolling hills with a bend in a river framed comfortably in the right-hand corner of the scene. There is a farmhouse in the middle distance; the horizon occupies the upper third of the frame. It is a classically pleasing landscape observing all the compositional rules of the golden section. As I watch the scene, still except for the autumnal foliage stirring gently in the foreground on the left, the frame to the right and below the horizon is gradually obscured by a slow fade up of a drawing in the pastoral manner of Claude Lorraine. It is of exactly the same view—the horizon lines match up—but disturbingly different: the river occupies a different channel, the frame widths don’t correspond, and the drawing is a reductive black and gray that represses the lovely autumnal light in the video footage. who’s view is this, and when? How do these different technologies of rendering approximate the act of anyone sitting and looking—Marie Antoinette, Cohen, me, or the unnamed home maker waiting for her honored guest? Cohen brings us so close, but only to the brink of an unrecoverable gap—a gap between past and present, and between perception and representation. It is also the unrecoverable gap between your subjective experiences and mine, or anyone else’s we might speculate about. Only the land remains as a reference point, but even its landmarks have changed.

Nicole Cohen, Driving, 2009. Video installation, 4:00 min. looped. Edition of 3, 2 Aps. Photo: Gene Ogami. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

Not one of the original structures of french Azilum remains; the whole enterprise survived only 10 years. The house purportedly built for Marie Antoinette, the grand Maison (the subject and title of yet another video on view here), boasted eight chimneys and a raft of aristocratic guests, but of course, not the Queen. If you go there now, you can apparently see a foundation, a few reconstructed out buildings and a museum containing some period artifacts, from whence come the drawings in Marie Antoinette’s Lookout and in another video, River Bank (2009). A fourth video, Driving (2009), shows the sunlit interior of what is perhaps the LaPorte house, built nearby in the 1830s by one of the children of the original french settlers. The room is furnished in neoclassical style in the Louis XVII manner; in the video, this shot alternates with an interior filmed at Versailles. In both of these views the camera is fixed, as if offering a full and leisurely inspection of these spaces as one might find in the pages of Architectural Digest or a tourist brochure. However, the pleasure of studying the details is denied us because both scenes are overlaid by an anxious tracking shot down a long country road at what can only be internal combustion speed. These waiting interiors are here charged with the anxiety of the chase, or the flight of the pursued without the balm of surcease, much less safe arrival.

Whatever her faults, Marie Antoinette never did say, “Let them eat cake,” nor did she survive to appear in real pearls to slop her own backyard swine. Home is an amorphous idea that continues to evolve along with our technologies—from firelight to light bulb to pixel to data spreading through the ether, miraculously liberated from the material encumbrance of bodies, spaces and stuff. Who waits, and where exactly? Do they worry over late arrivals? Do they keep the home fires burning and the linens fresh? And for whom do they wait?

Ellen Birrell is an artist and lemon farmer. She lives in Santa Paula, California.