NIC Kay, [GET WELL SOON] you black + bluised, 2018. Live performance, 60 mins. Performed at Abrons Arts Center, New York, May 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

My conversation with Kay, which took place via WhatsApp video call and email between March and June of 2020, stems from an introduction to their work by Nana Adusei-Poku (Kay’s partner), in 2016, and was more recently prompted by the February 2020 publication of Kay’s first book, Cotton Dreams. This handmade scrapbook of sorts uses collaged texts and images to unpack the history of cotton and the American slave trade while connecting it to cotton’s use and distribution today. Our conversation delves into their interest in exploring the nuances of Black lived experiences, asking urgent questions about the invisible mechanisms at play in oppressive histories and how that relates to architecture and movement. We have edited the interview for length and clarity.

JAREH DAS: You trained as an actor. When did you arrive at performance focused on movement?

NIC KAY: I’ve made the most of the positions I’ve found myself in, and I think it’s important to understand what your skills are and not miss where there’s an opportunity to grow. I initially wanted to act in plays, but I soon realized that auditions weren’t going to get me the kind of work I needed to grow as a performer. So, I started to develop ideas for one-person shows and became what some might consider obsessed. I persistently chased these ideas from various angles based on the skills and resources that I had at the time, which included styling and collage making. Seeing as I was never someone who could work fast, this one-person show process took me longer than I could have imagined. I began working with clothing in relation to the body to explore how to create a character physically, and then I started making collages as a way to visualize scenes and to determine settings. I must mention that I don’t make clothes, but I approach how the performer is dressed as an integral part of performance making. Style choices reveal dimensions of a person or place that words often omit.

When I was invited to perform solo in New York City for the first time, I did what was most comfortable, which was dancing, despite my other explorations. And I continued to do all the other things, interacting with clothing, collaging, scrapbook making, and of course moving. This was and is the scale of my practice.

Later on, when I lived in Chicago, I became more concerned with the theatrical aspects of the process, and I figured out how to choreograph by looking at videos of myself freestyling, which I had been sharing online. I am not a trained dancer, so I didn’t feel that I had the skills or the techniques to choreograph and remember movement for an hour-long performance. I used the computer and these videos to choreograph, which became an experimental performance script that fluctuated between coherence and incoherence. This way of documenting what were improvisations allowed me to remember where I needed to be. I believe the final performance was theater (although people from the theater world might not be consider it so), in the sense that it could be thought of as singular and unified, originating from a distinct set of social practices aimed at portraying aspects of human life.

DAS: I’m struck by how difficult it is to neatly package what you do. It’s about Black lives, performance, dance, movement, site-specificity, inviolable oppressive forces, and much more. It’s easy to label what you do as dance, but is this something you accept? What are your thoughts on categorizing what you do?

NIC Kay freestyling on video, 2013–14. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.

KAY: I have had a lot of reservations about being called a dancer, because I know dance history and have a lot of respect for the work and sacrifices of dancers. Often my interests are far away from traditional dance making but may later manifest as rhythmic movement. My entry into movement exploration is more of a conceptual exercise than an attempt to master form. I went to the Professional Performing Arts School, a public school in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City, for acting, where the standard of artistry was rigorous. Many of my classmates were already performing professionally as actors, musical theater actors, ballet dancers, modern dancers, singers, and musicians. We supported each other, but there was no interdisciplinary study. These strictly delineated lines between disciplines shaped how I saw a future career. After school, I tried auditioning for theater and film. Quickly, I began to understand and accept that my interests and abilities were a bit off-kilter. I was interested in being in plays and films that were experimental and challenging, maybe even hard to watch. I dreamt of playing characters free of the ridiculous constraints of race and gender-based casting. When I began to be cast in plays, it was as a cat, mouse, drag queen, zombie—some sort of creature or outsider character. It was great! I stumbled by chance into performance art auditioning for visual artists’ performance projects. At the time, acting auditions were listed in a newspaper called Backstage, and I just turned up to these strange auditions where I, the performer, was approached as a body—as material. In the visual art world, the boundaries and lines between disciplines that I had believed to be opaque were more transparent. I was able to weave in and out of different ways of working based on different projects and new skills. All of that is to say that I am now at a place where I feel very honored when people speak of my work as dance or of me as a dancer. I am an amalgamation of all the places I have been and the lessons I’ve learned.

DAS: You coined the term movement explorations as a way to describe how you move, with repetitions and slow movements. In pushit!!, for example, your body interacts with the rise and fall of helium balloons, and in some iterations, you lead an audience in an unconventional, improvised procession through streets named after prominent Black figures or through historically Black neighborhoods in the United States. Could you describe this term as it relates to your practice?

NIC Kay, pushit!! [an exercise in getting well soon], 2018–ongoing. Live performance at Pomona College Museum of Art, February 29, 2020. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

KAY: I wouldn’t say I coined the term movement explorations, but I use it often. These explorations are basically a way to get at the core of what is happening when moving the body is used as a tool to make liberation tangible, when movement becomes a chisel to deconstruct one’s environment. I have been exploring the limits of my body and the potential of the collective body. I am interested in how Black people, in particular, have utilized dance/movement to do these things. In most of the Americas, including the United States, enslaved Africans were denied the ability to assemble together for fear of revolt. When these Black people were able to congregate, they utilized the sounds and movements remembered from their homes to grapple with the reality of their new lives. They often also infused the movement from their labor into the new cultural movement vocabulary. Their polyrhythms and call-and-response techniques traveled from West Africa to New Orleans, New York, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Brazil, and the list goes on. The anthropologist, choreographer, and dancer Katherine Dunham traveled to the Caribbean to study folk dances and documented their forms and music. She saw the African roots of Black dance in these countries and made connections to her own culture as a Black American. From 1930 to her death in 2006, Dunham developed a technique that distilled these diasporas into American concert dance and dance history. I am deeply invested in Black Lives, the Black diaspora, and, as someone who grew up in New York City, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing and experiencing Black people from many countries and cultures. My friends and I created dances together mimicking our parents’ behaviors, sharing cultural traditions, and responding to the vibes of our neighborhood. This is my foundation—to think of movement in terms of anthropology and dance.

DAS: Do you look back even further to earlier histories of dance?

KAY: Due to my age, I am greatly influenced by the choreography of 1990s and early 2000s—reggae, dancehall, and hip-hop. The attitude, the fullbodiedness of the moves, the clothing silhouettes—all these elements shape the choreography. But I also look at a spectrum of dance histories, because you come to realize that, although there are new ways to move, you aren’t necessarily creating anything new but more building upon or alongside what has come before. I don’t mean to say that as a performer what you do isn’t unique, but after a while, you begin to understand the connections between the past and present. A year ago, I watched The Spirit Moves: A History of Black Social Dance on Film, 1900–1986 (1987), The Best of Soul Train, and binged #blackpeopledancing on the internet (via YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok), and the similarities between the movements [across media and time periods] were startling. There are, of course, differences, mostly relating to the wide range of music that dates each style, from early swing to blues to disco to R&B to hip-hop to trap, but the accompanying dances follow a clear lineage.

DAS: Site-specificity informs a lot of what you do. This is evident, for example, in some of the iterations you have done of pushit!!, where the performance has unfolded as a procession that begins with an audience in streets and then, at times, moves indoors. Some of the iterations also interact with architecture. How does your interest in site-specificity translate into a white cube or within the institutional framework of a museum?

NIC Kay performs Bruce Nauman’s Wall-Floor Positions (1968) at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2018–February 17, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

KAY: I haven’t worked with museums very much as a solo artist. Yet, I have performed in museums and galleries in the support of other artists’ works. I tend to work on multiple projects simultaneously, and works stem from the practicalities of what is available to me at a given time. My practice has shifted at times depending on my proximity to museum and gallery spaces. In the fall/winter of 2018, I spent hours each week in the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] and MoMA PS1 performing Bruce Nauman’s Wall-Floor Positions (1968) in twenty-eight-minute intervals. I was in a gallery balancing myself between a floor and wall for months. There was definitely a shift in my thinking in terms of how one responds to different sites and the challenges that ensue. I am self-taught, working mostly outside of these institutions and utilizing my own capital to fund my work. I work in a manner that is audience-facing, so it’s often easier to reach viewers with a low cost video that I can post on the internet than to wait to be commissioned by an institution. I am invited to perform the work pushit!! because it’s a great performance and because the budget is smaller than that of lil BLK (2015–ongoing). (lil BLK is a live solo performance influenced by New York City gay/queer ballroom culture, live punk shows, butoh, and praise dance that tells the autobiographical story of a fairy boi, child of god, little black girl, performer, and activist.)

NIC Kay rehearsing lil BLK (2015–ongoing). Performed at Hamilton Park, Chicago, March 16–18, 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Nana Adusei-Poku.

For pushit!!, I don’t have a team of people traveling with me, there is no group choreography, and no stage manager or lighting designer. I have begun many conversations with programmers and curators about touring lil BLK and then, after sending the proposal and budget, the conversation shifts to pushit!!. That said, I don’t necessarily make art for the museum-going (white and middle-class) audience that has a dominant presence at performance venues, galleries, and museums, although these audiences are welcome to the work. So much of the work has to consider that reality, but I am cautious of looking to these spaces and audiences for validation. I mean, whether or not they clap, the work persists; whether or not I’m commissioned, the work will be made.

DAS: I am also interested in how you converse with space: architectural space, public space, other bodies, and audiences. How do you navigate the production of both physical and metaphorical space?

KAY: There are external forces beyond my control that have influenced the choreography of some of my movements. These choreographies dictate how I orient and navigate spaces and people. This is not a contemporary phenomenon. For a long time, I didn’t know what or who was controlling my choreography, but I had an embodied understanding that certain configurations and materials allowed a particular type of potentiality, intimacy, and forgiveness that others didn’t offer. This is the difference between grass and concrete. Sharp or rounded edges. Sun-facing windows or windows that get no direct natural light. This is the reality between tenement living, public housing, low-income housing, and choice. The choice to determine the width and dimensions of one’s living spaces. The choice to determine who you want to build community with and what your surroundings should be and the power to make it happen. New York City’s urban planning history is riddled with records of betrayal by design. The city has for hundreds of years favored the mobility and imagination of those with power, influence, and proximity to whiteness. This [history] manifests in structures that have moved Black people in particular from margin to margin across the five boroughs. This displacement choreography acts as the equivalent of what could be bodies being pushed and dragged across the city. The two modes or tempos of movement Black people have impressed upon them are a sort of motionlessness and fast-paced jolts. This city has been a place for Black people and other oppressed populations to stake a claim on space and direction. Put simply, I spend a considerable amount of time researching who planned what, who was the architect, why certain designs were made, and what were the consequences, in tandem with what are the realities of grappling with the lived reality of these choices. I have recently started rereading Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (2012), by Mabel Wilson, and Dark Space (2016), by Mario Gooden, both of whom are architects and Black scholars at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University, New York City.

DAS: So, walking around these sites in real time became a way to relive and probe these contested histories of place?

KAY: Yes, walking is a way for me to explore some of the sites in places I’ve located on maps but haven’t experienced physically. Often, in the United States, when I’ve been invited to present pushit!!, I look for a neighborhood that has a visible sign of being a Black neighborhood, a street named after Martin Luther King or a local civil rights leader, for example, is a big clue. I usually start from such markers and research further about the area. I physically create the pathway for the performance based on a set of questions I intend to probe with the work. Usually, these questions are: What is my relationship to this space? How is my body framed and potentially viewed in this space? Is the environment conducive to movement and forgiving of mistakes of the body? What are the emotional memories of the path I’ve chosen? How have Black people come to be in or not be in this space? And the list goes on.

NIC Kay, pushit!! [an exercise in getting well soon], 2018–ongoing. Live performance at Pomona College Museum of Art, February 29, 2020. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

DAS: You’ve explored the book as a medium for over a decade, culminating in the recently published Cotton Dreams. It is also a subject you intend to examine during your residency at the Center for Book Arts, New York (which is on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic). What does publishing mean to your practice?

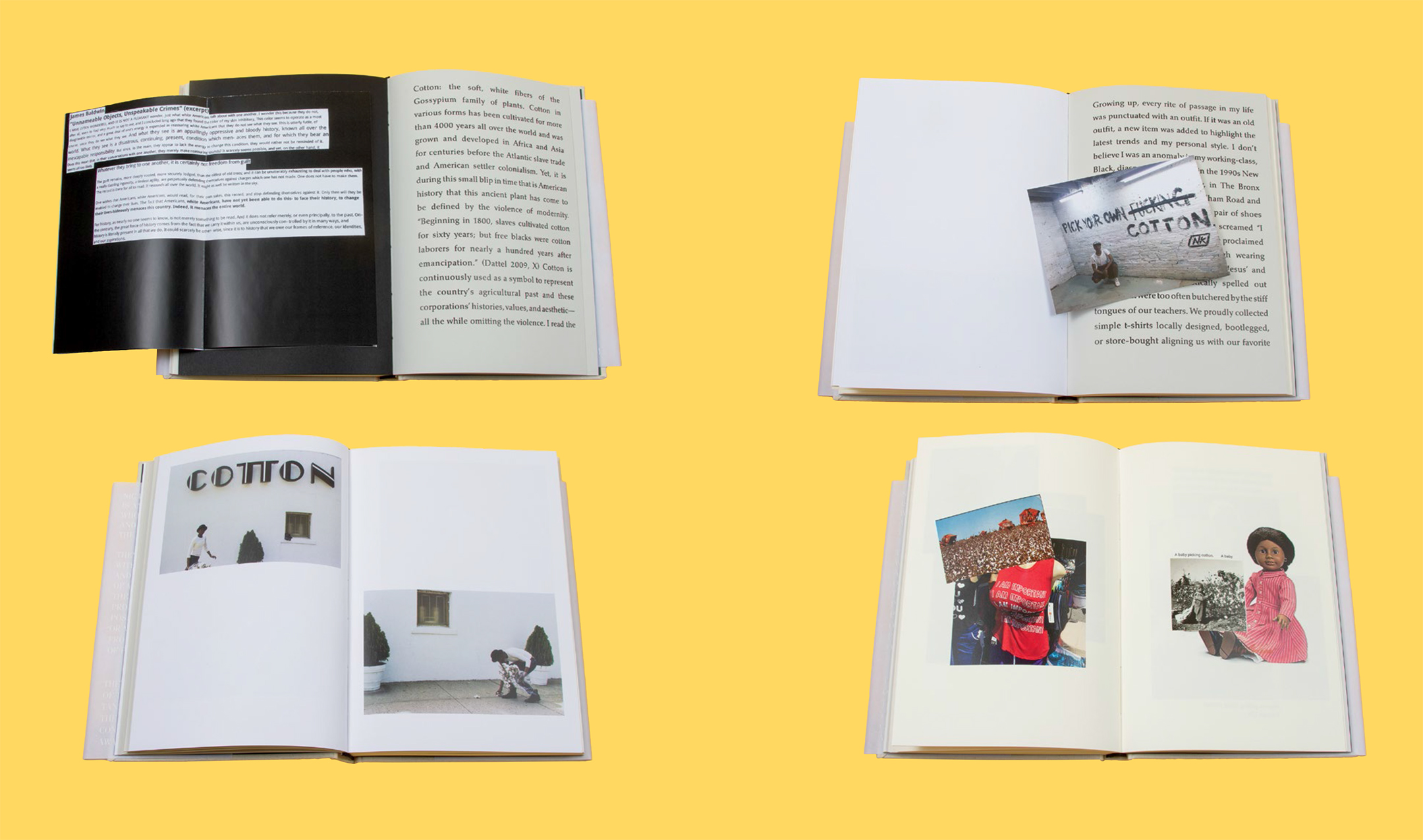

KAY: The idea for Cotton Dreams came out of an experience where I was given a bouquet of cotton by a white woman I did not know, in New York, in 2008. That event spurred an avalanche of shifts in my life. My approach to knowing and the truth was altered. I became consumed with questions of lineage and responsibility to Black people other than myself, including those who are no longer alive. I started thinking a lot about American history in relation to the history of enslavement and the diaspora, and I began reading about race and representation.

At various points while working on this project, I had to face the reality that Cotton Dreams wasn’t a one-person show, despite the time I spent trying to make it into one. I realized that I wanted to work in two dimensions with the material that I had been slowly gathering since 2008, via writing, photography, and collages, rather than trying to bring it to life onstage. In tandem, I began performing short pieces about my body, femininity, and Blackness, which felt more pressing at the time, whilst Cotton Dreams continued to develop in my sketchbook. Making Cotton Dreams [which eventually took the form of a published book], took a long time and was a slow and at times painful process.

The physical labor of the printing process that went into making the book has been exciting to witness and surprisingly has sparked a performative interest [for me] in relation to bookmaking. Although my workspace residency at the Center for Book Arts in New York is currently on hold, I am presently thinking through what the obscuring and making invisible of labor in manufacturing does to the ways we value objects. All of this has made this edition of one hundred handmade books even more special. This has been a four-year journey for me working with the publisher, Matt Austin, at Candor Arts. We carefully put this whole thing together with a lot of consideration for the material connections to the topic, the haptic experience of the object, and ways to develop a book form that could perform my voice. It’s a mix of visuals and textures brought together to explore the history of slavery in relation to the clothes we wear today and to ourselves as modern consumers. I want people to engage with the book actively and to sense shifts in the narrative with their hands.

Spreads from NIC Kay, Cotton Dreams (Chicago: Candor Arts, 2020). Courtesy of Candor Arts.

The last thing I would say is that I was very interested in narratives of freedom and enslavement of the late 1800s and 1900s, and how that was an important part of Black people’s assertions of the self, pushing the abolitionist project, and speaking to the horrors of slavery. A lot of this was done through book form, and that was how people were able to appeal to what you could call “sympathetic white folk.” What could happen onstage at that time in the late 1800s to 1900s was in stark contrast to the first-person narratives shared in these books. There were the performative speech acts of Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, amongst others, but speechmaking was not the dominant form of performance at the time, minstrelsy was.

When writing the text for Cotton Dreams, I kept Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) in my mind’s eye. I was moved by the claim in this and other narratives for personhood and freedom to determine one’s humanity by using words in ways that were kept from the enslaved, words that made them fugitive, free, and remembered. I hold these histories inside of me. I am encouraged by the work of these early Black American artists in moments where it feels impossible and dangerous to say the hard but necessary things. Could I have made pushit!! or Cotton Dreams at any other time? I don’t know, probably not in the same ways they appear now. Many have come before me, and many will come behind. But I am of this particular moment in time.

Jareh Das is a curator, writer, and researcher based in London and Lagos. She holds a PhD in Curating Art and Science from Royal Holloway, University of London, for her thesis Bearing Witness: On Pain in Performance (2018).

NIC Kay is from the Bronx. They are a person who makes performances and creates/organizes performative spaces. Their work choreographically highlights and meditates on Black life in relation ship to space, social structures, and architecture through centering embodied practices.