More than a few viewers commented on the diminutive scale of the New Topographics re-run at LACMA this past fall. Sidestepping the finer points of what got left out, added in, rearranged, or wholly changed (all of which have been taken up in detail elsewhere), this perception of lack has to be measured against the lavish space that this exhibition has been afforded in the cultural memory banks. Even bearing in mind the succession of MoMA exhibitions that sought to put photography on the art-world map–from Edward Steichen’s jingoistic reformulations of Soviet agitprop strategies for homeland purposes during the war years to John Szarkowski’s postwar attempts to fix the specific attributes of the medium in properly Modernist terms–there really is no other show that has had a comparable reciprocal impact on the development of contemporary art.1 From Conceptual Art to “Identity Politics” to the return of the tableau picture form in current German art photography, all can be described as variations on a theme established here. The LACMA re-hanging is timely, to say the least, and it is perhaps due to the expectation of a seamless overlap between then and now that every irregularity comes to stand out so sharply.

If this exhibition now strikes a slightly underwhelming note, it is because we expect more, and this expectation responds as much to what photography once was, as a form of artistic practice, as to what it is now. In 1975, when these artists and works were initially assembled under the banner of a new movement, the question could still be asked: just what kind of movement is it? In 1975, that is, this “primary question,” as Walter Benjamin famously put it in his essay on “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” had not yet been settled.2 Although it may well be uppermost in the minds of producers and recipients alike, “the question of whether photography is an art” is, in Benjamin’s estimation, secondary to that of “whether the very invention of photography had not transformed the very nature of art.”3This “primary question,” still latent in 1936 when his essay was written, could at last be articulated, and this is exactly what the New Topographics exhibition did when it was first shown at the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, in Rochester, New York, in 1975. What it does the second time around is to commemorate the event as a collision between two still very separate disciplines, discourses and institutional contexts, while providing the opportunity to revisit, with diagnostic hindsight, the as yet uncertain prognosis of its fallout.

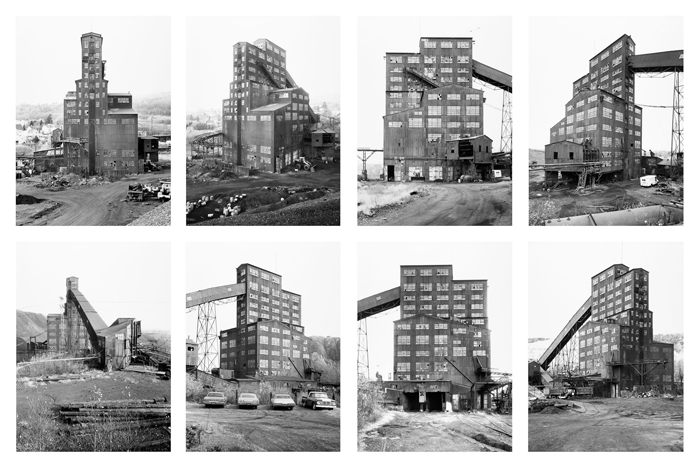

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Harry E. Colliery Coal Breaker, Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, 1974. Eight gelatin silver prints; each 16 x 12 in. Lent by Hilla Becher in association with die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur,

For those who had taken up the cause of New Topographics, the artistic potential of photography was found to reside in most quotidian applications of the medium as a means of observation and analysis, but taken up a notch technically. Submitting the journalistic photo-document to a finely tuned aesthetic makeover, their works still appear to conform most closely to the program set by Szarkowski where, again, it is painting that sets the agenda for postwar modernism in the reductive pursuit of ontological essence. Paring away every extraneous element, art could be remade, as if from scratch, from the elementary properties of its medium. To make “art for art’s sake” is to make art from, and about, art, which is somewhat more easily imagined in the case of painting, where the thing that is made really is made of the thing. In the case of photography, however, something else always intrudes.

This something else would have to be the world, and with it, those “ideas which,” as Clement Greenberg wrote in his 1940 essay “Toward a Newer Laocoon,” “were infecting the arts with the ideological struggles of society.”4“As the first and most important item upon its agenda, the avant-garde saw the necessity of an escape from ideas,” he declares, this being the one thing photography just cannot do, although not for lack of trying.5 The challenge to transform the photograph into a painting of sorts had already been met in various ways: in the choice of painterly subject matter (clouds, water, reflections, distortions), painterly views (over- and under-exposed, off-kilter, blurred, trailing), and painterly printing (through gauzy fabrics, “sandwiched” negatives, the obstructions and openings of “dodging” and “burning”). Adherents to the mode of New Topographics largely dismissed these pictorial tactics as wrong-headed in favor of a more uninflected aesthetic that might best be compared to that of the Neue Sachlichkeit in interwar Weimar Germany (sachlichkeit: clear-sightedness, sobriety). Much like August Sander, Germaine Krull, Karl Blossfeldt, and Albert Renger-Patzsch, these American photographers seized upon the objectivity that is inherent to the function of their apparatus as a medium-specific command, thereby fulfilling photography’s Modernist promise, while at the same time advancing a critique of subjectivism as an element equally integral to the medium of painting.

Joe Deal, Untitled View (Albuquerque), 1974, printed 1975. Gelatin silver print, 12 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. George Eastman House collections. © Joe Deal.

The perception of smallness that pervades the New Topographics exhibition overall is caused not by the number of works on offer–there are more than enough; if they were paintings, there would be too many– but by their diminutive scale. These tend to adhere to the then-standard format of the eight-by-ten-inch print, enfolded in a narrow matte and thin frame. With presentation set on the default mode, the “choice of no choice,” as Uta Barth likes to say, these pictures make a point of seeming generic. Of course, they are anything but–especially in the space of the art museum. Now, as then, one might want to step back for a moment of pause, for couched in the very sense of disappointment that is provoked by this adamantly “minor” art is a subversive charge, and it is aimed squarely at the “majors.” As one would expect, New Topographics enacts its modernity as a form of self-critique but, this being photography, it is a critique that necessarily oversteps its territorial bounds. Whereas, by the sixties, Greenberg was reformulating the already isolationist agenda of Modernist painting in terms of “entrenchment,” that of photography would open ever further outward, annexing all the remaining provinces of art–after painting, sculpture, installation art, earthworks–and then exceeding them.6 The very modesty of its presentation disclosed immense ambitions.

Almost a half-century later, photography and painting no longer vie for the keys to the kingdom of the art-world, but rather a fair share of real estate on the wall. In Germany, the students of Bernd and Hilla Becher, the legitimate (blood) heirs to the Neue Sachlichkeit, have since gone on to explore the possibilities of color printing, while simultaneously super-sizing their pictures to the scale of New York School Abstract Expressionism. The fact that pictorialist largess is now the lingua franca of art-photography speaks to the intrinsic futility of politicizing questions of form, and yet… The very reticence of these earlier works to provide the sort of aesthetic thrills that gallery-goers expect may now be seen as their strongest suit. Above all, New Topographics represents an exercise in stylistic restraint, keeping authorial input to the minimum condition of choosing one part of the world over another. Choosing, as Duchamp had already demonstrated, is all that the artist ever does anyway, but rarely is it done so emphatically. It is therefore an acutely Duchampian, Conceptual path that unfolds before these artists as they set about to align the art-function of photography with the model of the ready-made. “Found” is exactly what the world becomes in the lens of the camera, which is of course a kind of “found object” itself.

John Schott, Untitled, from the series Route 66 Motels, 1973. Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 in. George Eastman House collections. © John Schott.

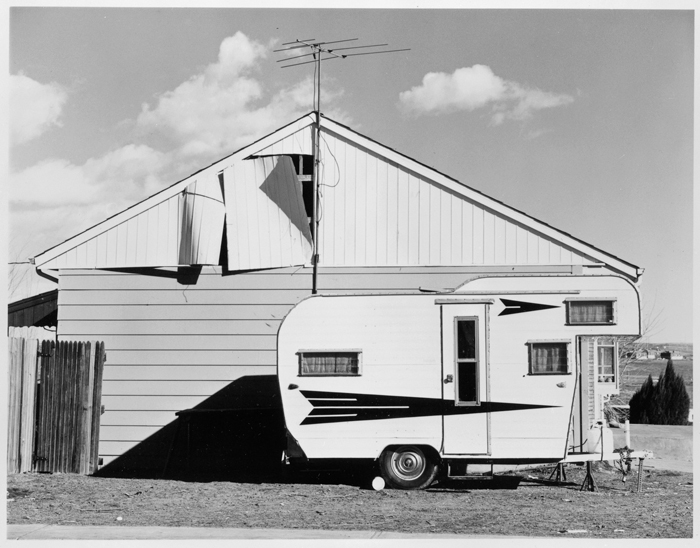

The inclusion of the Bechers’s ongoing typographic inventory of early industrial forms, caught in the process of transition into the period of “post-Fordism,” serves as the literal nexus between New Topographics and Neue Sachlichkeit. As the only “non-indigenous” practice in the show, it also serves to connect the fates of two countries, Germany and the U.S., at a time when the latter first came to shoulder some of the guilt of the former. The period of the Pax Americana had just been revealed to be only nominally “postwar,” as the Vietnam imbroglio stood to confirm. The misuse of Power in the Pacific, to quote the title of one of Steichen’s most hawkish curatorial efforts from 1945, hangs over these photographs like a dark cloud; even those that might be dismissed elsewhere as folksy Americana, like John Schott’s Route 66 series, are touched by its shadow. Accordingly, the black and white picture overwhelmingly favored by the champions of New Topographics is purged of any errant trace of “old-timey” nostalgia. Now more than ever, its tone is noir through and through, and once again, this is due to the sinister convergence between what these photographs show us and when. After Iraq, the prospect of a “New American Century,” here shown in full swing, has never seemed dimmer.

One can easily imagine how color would have given these photographs a more celebratory, Pop-ish aspect. Accordingly, its absence may be seen as largely rhetorical. But there is also a more pragmatic explanation, as color is by nature seductive and distracting, and thereby fundamentally unsuited to the sort of strict topographic description that is the whole raison d’etre of these works. The goal, especially evident in the pictures of Joe Deal, Robert Adams, and Lewis Baltz, is to document our social incursion into a landscape still partly wild, and to do so critically, under the negative sign of domination. This, at least, is the political rationale that these photographers append to their subject matter, which reflects the dismal sprawl of standard-plan suburbia and industrial parks into the furthest reaches of the American outback. Following the precedent of the Neue Sachlichkeit, their vistas are depopulated as a matter of course, since here as well the principle of objectivity is one that consigns the picture from and to objects. The very absence of human subjects within these “neighborhoods” still under construction gives to the cloudless skies above them an apocalyptic, radioactive glow. They might as well be ruins already.

Robert Adams, Tract House, Westminster, Colorado, 1974. Gelatin silver print 8 x 10 in. Gift of the photographer. George Eastman House collections. © Robert Adams, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

I want to suggest that there is a consistent tone to New Topographics photography, and while it can be traced to the choice of subject matter as much as the innate operations of the medium, it cannot be confined to them. In the case of the Neue Sachlichkeit, questions of form and style were elided via an ethos of straightforwardness, or “matter-of-factness,” as Benjamin described it.7 The core principles of centrality, frontality and neutrality, still evident in the work of the Bechers, are subtly readjusted by their American colleagues in pursuit of increased compositional leeway. If Baltz’s pictures constitute the representative acme of the New Topographics exhibition, then this would have to do as much with their proposed objectivity as their diffident aestheticism. The truth-telling mandate of the photo-document, its doxa, is here blurred ever so slightly, in a way that invites comparison between the politicized picture-form and the sorts of hard-edged geometrical abstractions that one might imagine as its very antithesis. Certainly, such confusions supplied the movement’s original critics with a damning argument, but today, when the lines between aesthetics and politics are no longer so clearly drawn, they appear undeniably forward-looking.

Lewis Baltz, South Corner, Riccar America Company, 3184 Pullman, Costa Mesa, from the series New Industrial Parks, 1974. Gelatin silver print, 6 x 9 in. Gift of the photographer. George Eastman House collections. © Lewis Baltz.

As opposed to the “broad-brush gestures” favored by what could be called the Neue Neue Sachlichkeit—Thomas Struth, Candida Hoefer, Thomas Ruff, et al.—the New Topographics photographers re-pictorialized the photo-document in minute, exacting increments. In between their two moments, the “art concept of photo-journalism,” as Jeff Wall describes it in his position paper, “Marks of Indifference,” gives way to the emergence of art-photography proper at the hands of the Conceptual generation.8 This transition is acknowledged in the LACMA exhibition through the inclusion of two key works of Conceptualism, Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) and Dan Graham’s Homes for America (1966), which are presented face-up in a vitrine alongside their non-art counterpart, Robert Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas (1972). Here, as well, one may observe the reformulation of a Neue Sachlichkeit-style typographic model for specifically American purposes, but now in a blatantly amateurish manner. It is by way of “de-skilling”—as per Wall, an all-out rejection of photo-specific formalism right along with the tradition of the fine print–that the medium finally clears the art-world hurdle.9 Ruscha and Graham seized upon photography as an authentically popular art, or more to the point, a middling one (“un art moyen” in the words of Pierre Bourdieu), and treated it accordingly. By making their work as lightweight and disposable as possible, they raised a range of object-adjacent questions pertaining to authorship, context, and art’s social function. These same questions were no less central to those in the New Topographics movement, but they instead tried to provide answers in their works.

The contributions of Ruscha and Venturi, whose working relationship is a matter of record (Venturi was a self-proclaimed “student” of The Sunset Strip), play up the Western orientation of New Topographics. As with Sander and company, these photographers were drawn to the archival mode by a sense that the landscape was changing too rapidly for human perception and memory to keep pace, and nowhere was this truer than in the West. The aggressively uprooting and displacing character of this change is emphasized in the works of the Conceptual generation, which routinely take the form of the travelogue, but it is in New Topographics that it first comes to be recognized. The Neue Sachlichkeit were likewise mobilized by intimations of crisis; they took up the cause of preservation on foot, as if determined to remain connected to the land and its people–those so-called “first men” of Sander’s first portfolio. In contrast, the pictures of the New Topographics are fully motorized. Documenting the transfiguration of the landscape by car-culture, they are simultaneously records of a new way of being, as it were, “on the road.”

Elsewhere, this fleeting, transient view of life was celebrated as part and parcel of the postwar American experience, but not here. Viewed through the lens of New Topographics, the world appears forlorn and utterly uninviting. At LACMA, these alienationeffects were given a pointedly literal spin by way of one last addendum: a new film by the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI), set on repeat play in a partly sealed-off space at the very center of the exhibition, that submits the local landscape to sweeping probe-like observation in search of oil fields. The inhuman height of the camera’s overview combined with its dead-smooth tracking of the land below is inarguably off-putting, but the clincher in this regard is the bone-rattling drone of the film’s soundtrack. Ominous in the extreme, its insistent, low-end thrum permeated the surrounding galleries and every photograph inside them in its doomsday atmosphere.

Installation view, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, October 25, 2009–January 3, 2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo © 2010 Museum Associates / LACMA.

Installation view, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, October 25, 2009–January 3, 2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo © 2010 Museum Associates / LACMA.

Certainly this was the boldest curatorial intervention on the original plan of New Topographics, and on the proposal of an accurate, archival reprise of the exhibition as time capsule. To say that the CLUI contribution divided the audience would be generous; most found it overbearing. But what if this was exactly as it was meant to be? The value of overstatement tends to be underestimated, especially in the museum, where one might prefer a gentler sort of provocation. In this context, the all-out assault of the film seemed to be all the more out of place, which is not necessarily such a bad thing. As such, it may help to remind us that the New Topographics movement was never quite integrated to begin with, neither in art nor photography. The awe-inspiring rumble of that soundtrack, which channels the “voice of god” one moment and B-grade sci-fi the next, exerted a preemptive strike on the very notion of historical aura that certainly would have graced these pictures in its absence. Here instead they were set on a precarious knife-edge of under- and overreaching, their smallest details trembling with epic foreboding.

Now that petrochemical intrigue is no longer a subcategory of conspiracy theory, but a simple fact of life, the outsider postures of New Topographics seem perfectly appropriate. It is not only American society that is taken to task, but American art. Moreover, it is the secret collusion, in America, between Modernism and modernity–the first, under the cover of autonomy, and the second, populism–that these photographers seek to expose at the very moment when they appear furthest apart. Apartness is here understood as one more symptom of the modern process of compartmentalization in which everyone participates equally, “advanced” artists and real estate developers alike. At its best, the New Topographics picture would catch these two parties in the midst of their ongoing negotiation, as the ostensibly “purified” logic of hard-edged abstraction gets laid like a prescriptive map over a territory soon to yield a grid-work succession of master planned communities and malls. Those who would still dismiss this as a “wannabe” mimicry of art, Modernism carved into bite-sized chunks, have simply confused the work with its referent. Instead, I suggest the analogy of the bitter pill.

Jan Tumlir is a member of the X-TRA editorial board. His articles and reviews appear regularly in Artforum and Flash Art. His last book, Desertshore, was published in 2008 by 2nd Cannons Press. Tumlir teaches classes in art history and theory at UCLA and Art Center.