Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021. Video still (detail). HD video, color, sound; 12 min. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates.

The title of the 2022 Whitney Biennial, Quiet as It’s Kept, forewarns that the motivations behind this survey of American art will remain oblique. For Whitney curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, “quiet as it’s kept” sets an intention that plays out as a tone poem, annotating the highs and lows of the pandemic life from which we are now gingerly emerging. Like other Whitney Biennials since 2000, this version has expanded its geographic scope to include artists from Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Still, in this iteration, the values and desires of the present moment are primarily symbolized by US-centered movements, like Black Lives Matter and Standing Rock, in addition to the global Covid-19 pandemic and a sense of collective burnout from capitalist exploitation of the past and present. The horrors we have collectively witnessed bring to mind Toni Morrison’s wisdom, from “Quiet as it’s kept,” a story of incest and racial oppression embedded within her novel The Bluest Eye: “There is really nothing more to say—except why. But since why is difficult to handle, one must take refuge in how.”1 Reeling as we all are from these experiences, the curators must walk a line between the disruptive realities of the past two years and the interests of the Whitney’s support base, which includes some of New York’s most comfortable power brokers. As a result, this Biennial keeps its cards tightly pressed to its chest; every curatorial choice is a tacit acknowledgement that their critical work is difficult to do within the framework of a mega-exhibition inside a contemporary mega-museum.

The Biennial is organized into two primary spaces. It begins on the sixth floor, where the galleries are painted black. The artworks are installed within a series of confined spaces, and the tenor alternates between serenade and assault. At the entrance, large black-and-white paintings by the late Trinidadian artist Denyse Thomasos provide a clue to the exhibition’s framing. Titled Jail and Displaced Burial/ Burial at Goree (both 1993), they respond to what Thomasos has described as a concept of Black racial consciousness shaped by the smallness and isolation of the slave ship hold, the prison cell, and the grave. By beginning with Thomasos, the curators suggest that the exhibition design of the sixth floor is a kind of “hold,” an idea central to Afropessimist discourse that I will articulate through the language of its proponents Saidiya Hartman, Frank Wilderson III, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, and Christina Sharpe.

The hold is the realm of logistics, of deep storage, of commodities, “the ones that could speak.”2 Its logic is that of efficiency, moving units of one kind or another across vast distances quickly to extract profit. Wilderson argues that it is the memory of the hold—not the quest for freedom—that defines the Black experience or Black radical consciousness. He prefers “to stay in the hold of the ship, despite my fantasies of flight.”3 Wilderson’s thesis is that citizenship or legal personhood remains a state of being defined and described by white maleness; those who deviate from this norm are always granted subjectivity, not innately in possession of it. As Frantz Fanon would say, “The black man has no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man.”4 Black subjectivity, according to Wilderson, is by necessity a void or absence, because it exists as the negation of a white man’s positive expression. He implores readers to reject that baited gift of subjectivity, what we might call visibility to the dominant culture, with its attendant rewards that serve our vanity at the expense of our autonomy. His advice is hard to swallow, demanding as it does a rejection of social comfort for something more bitter and honest.

Denyse Thomasos, Displaced Burial / Burial at Gorée, 1993. Acrylic on canvas, 108 × 216 in. Courtesy of the Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto.

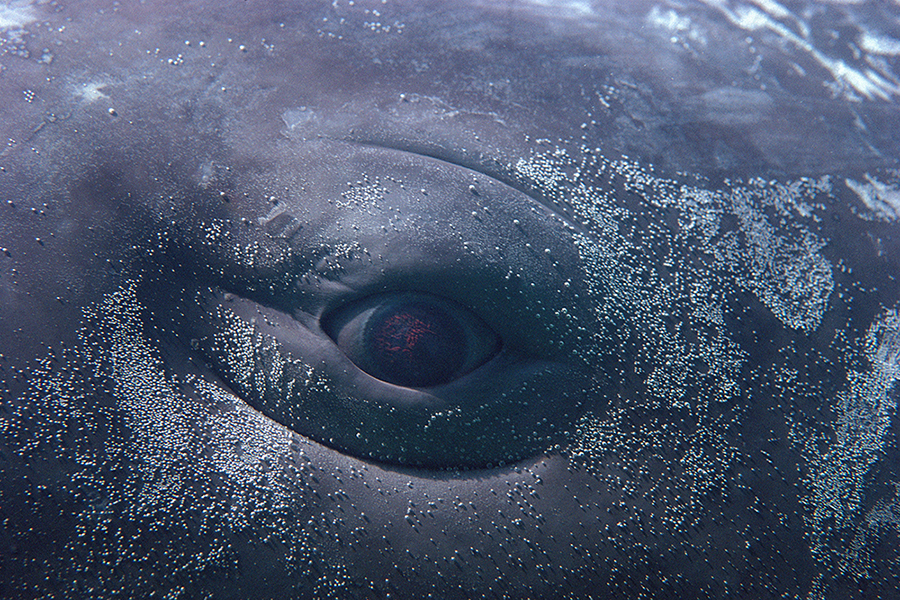

Below the darkened sixth floor, the fifth floor is open, daylit and full of abstract paintings hung on open wooden armatures and works that change or move during the exhibition’s run. It is tempting to see the binary conceit of Quiet as It’s Kept as a reinscription of Wilderson’s admonition, in which the dark void of the sixth floor is cast as the negation of a white institution’s positive expression on the fifth. Moten and Harney describe the hold as a place with “no standpoint,” and this biennial is always shifting, unclear of where to stand. Another reading of the exhibition design is proposed on the ground floor, where the visually enthralling film EXTRACTS (2022), by Moved by the Motion (MbtM), plays on a loop. This film was created using footage and archival material from MbtM member Wu Tsang’s full-length film and staged performance MOBY DICK; or, The Whale (2022), which is an experimental retelling of Herman Melville’s novel of 1851. EXTRACTS is presented on a curved screen that sits atop an angled wooden platform resembling the deck and hull of a ship.

Moved by the Motion, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, 2022. Directed by Wu Tsang, Schauspielhaus. Video still. HD video, color, silent, and performance. Courtesy the artists.

The appearance of the whale occurs well into the EXTRACTS video; up until this point, the crew of the Pequod appears to live a nearly childlike existence without care or forethought. Languid days of quiet intimacy are interrupted only by the occasional drunkard or cleaning task, until the obsessive Captain Ahab drags the whole crew into slaughter and their eventual doom. Pervasive throughout is an affect of exhaustion: bodies hang, fold, and slump. Individual vignettes follow characters played by Boychild and Fred Moten. Moten’s monologue, the only speech heard in the film, resonates with his philosophy of the undercommons as the realm of the undercompensated and disenfranchised. Moten’s character relates capitalist malaise to Wilderson’s concept of an Afropessimist layer below the surface of the water, in the depths that submerge the ship’s hold as it floats along the dark ocean of the mind. MbtM’s multiracial casting is not a revisionist update; Melville’s cast of characters deliberately included North American and Polynesian Indigenous crewmen and several Africans. The author hoped to present his nineteenth-century readers with ennobled representations of people of color that would oppose the racist representations they were likely to encounter elsewhere. MbtM has included several transmasculine performers among the crew, which speaks to a similar interest in countering negative representations. The sailors’ insouciance recalls Hartman’s descriptions of “wayward” queer African Americans, whose lives were lived without ambition or caution and thus were perceived as threatening to the white social order. The whale itself is similarly wayward, as it defies the authority of Ahab to control, capture, and kill it. The crew does manage to harpoon a whale, dutifully processing the meat and blubber. As they do, the ocean opens a massive vortex, sinking the Pequod. The watery death wrought by Moby Dick brings an end to the Fordian machine of colonization into which the crew themselves have been processed. Like a resurrection, the film restarts, and the idyllic pre-colonial life of the Pequod is poetically restored.

Moved by the Motion, MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, 2022. Directed by Wu Tsang, Schauspielhaus. Video still. HD video, color, silent, and performance. Courtesy of the artists and Design Pics Inc/Alamy Stock Footage.

As the ocean bobbed and waved onscreen, I pictured the whole of the Whitney as an inverted ship: bow at the base and hold at the top, like a braincase within the architecture. The open fifth floor, with its emphasis on emotive abstraction, changeability, and labor, might be the deck. In my mind, I read this as an Afropessimist inversion of David Adjaye’s design for the history wing of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), in Washington, DC, which one enters three stories below ground level. The NMAAHC’s optimistic design leads visitors through dark corridors where the history of Black enslavement and oppression is described, then periodically releases its audience upward into light-filled atriums where resistance and freedom are represented. The Whitney Biennial galleries are organized by a similar if inverted logic, which visually and structurally reinforces an Afropessimist reading of the works.

Two video works by African American artists on the sixth floor further drive my framing of the biennial as Afropessimist: Adam Pendleton’s documentary on longtime civil rights activist Ruby Nell Sales and Coco Fusco’s meditation on New York’s Hart Island—where, since 1869, more than a million people who died indigent or whose bodies went unclaimed have been buried in Potter’s Field, many in mass and unmarked graves. In Pendleton’s video, Sales recounts her experiences as a voting rights organizer during the Freedom Summer and the murder of one of her colleagues, a white man, by white supremacists. In the context of Pendleton’s large black-and-white, text-heavy canvases, the theme of testifying—spiritually, legally, or emotively —recurs. In her video, Fusco rows a small boat around the perimeter of Hart Island, home to the graves of many of COVID-19’s poorest victims. She drops white flowers into her wake while a drone films her boat drifting through the water where the East River meets the Long Island Sound. Fusco never mentions HIV/AIDS, but the afterimage of that prior pandemic is everywhere in a post-pandemic landscape that renewed the demand for mass, unmarked burials on Hart Island. Pendleton’s and Fusco’s works ask a question, outright or implied: How far, really, have we come?

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021. Production still. HD video, color, sound; 12 min. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York. Photo: Geandy Pavón.

The installation of works on the fifth floor presents a deceptively simple meditation on curating as an action and a job. What do curators do? In the most basic sense, they move pictures around, and this process of storing, selecting, moving, and framing provides a curatorial conceit. The fifth floor is characterized by an instability that creates a buoyant sense of change. Though the exhibition begins on the sixth floor, moving in reverse on my second visit revealed certain curatorial choices more fully. Visually, the fifth floor recalls a “visible storage” gallery, such as those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Broad, in Los Angeles, where vitrines and racks store artworks in the collection that are not on display in the public galleries. Most objects in museum collections are confined to the depths of storage (a kind of hold usually located in a basement or sub-level); the Whitney’s gesture toward this relatively recent trend in museum design advances the sense that the artworks have been released from some invisible constraint. Visible storage reflects the inability of institutions to display more than a part of their collections at a time, and they can serve as an impetus for artists to mine collections for evidence of underrepresented cultures in study collections, ephemera, and archaeological object collections, as well as fine art galleries. Artists who practice institutional critique, including Fred Wilson andJames Luna, helped to force the rewriting of cultural mandates in modern museums by intervening in historical collections, as did scholars and curators seeking to make cultural heritage more accessible to the Indigenous and formerly colonized or enslaved communities from which collection objects often originated.

Quiet as It’s Kept includes a smattering of works that treat the archive as a subject as well as material, including Renée Green’s multi-panel installation and a documentary film by Trinh T. Minh-ha, but they lack the kind of clearly stated throughline that one might expect in a traditional art or history museum display. The exhibition includes historical material, a methodology derived from decolonial politics applied to anthropological practices, as another way that “personal narratives sifted through political, literary, and pop cultures can address larger social frameworks.”5 This is a missed opportunity to address the tremendous changes occurring in the form and treatment of historical archives due to the advent of digital technologies. I am unable to determine whether Quiet as It’s Kept reflects curatorial resistance to explicitly political and decolonial framings of artworks in favor of personal narratives as a response to our oversharing internet culture, as a defensive posture to protect the curators from institutional backlash, or because the curators are resistant to an “identity politics” narrative that would link their show too closely with the controversial 1993 Biennial that ushered in that framing.

Renée Green, Excerpts, 2020. Double-sided banners of polyester, nylon, and thread, 42 × 32 in. each. Installation view, Bortolami Gallery, New York, 2020. Courtesy of the artist, Free Agent Media, and Bortolami Gallery. Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

The fifth floor is laden with objects, including a few large sculptural works and a lot of abstract painting. “Abstraction,” the curators write, “demonstrates a tremendous capacity to create, share, and sometimes withhold meaning.”6 Much of the painting on view is by artists of color, including Indigenous artists. Contemplating Canadian Omaskêko Ininiwak artist Duane Linklater’s large abstractions, which he creates using the canvas and linen pattern forms used in making animal-skin teepee covers, I questioned the ways that the works’ framing here implies that they are contiguous with the American tradition of abstraction in which the narrative of American art—and the Whitney collection— are heavily invested. Linklater, who uses traditional pigments, such as sumac, charcoal, and cochineal, informs his work with spiritual meaning, which western critics of painting in the twentieth century have often discouraged. Nearby, Lisa Alvarado invokes Indigenous feminism and decolonial cartography in her colorful, fractal-like works using acrylic, ink, gouache, canvas, burlap, fringe, polyester, and wood. Dyani White Hawk uses glass beads on aluminum to create “Lakota abstraction,”7 which shares the geometric repetition and the modular format of Minimalist art but comes from a distinctly different place of origin conceptually. In contrast, Pendleton is one of several artists at the Whitney who reference the canon of western Modernism explicitly in order to rework it. Also in this latter vein are MbtM’s EXTRACTS, a meditation on idleness, natural forces, and posthuman embodiment, and Alex Da Corte’s high camp contribution on the fifth floor, ROY G BIV (2022), an installation and a film that features the artist as Marcel Duchamp.

Alex Da Corte, ROY G BIV, 2022. Video, color, sound; 60min.; wood box with back-projected screen, paint, performance, and powder-coated chairs. Installation view, Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022. Courtesy the artist; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles; and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

In ROY G BIV, which plays as a rear projection contained within a large colorful wooden box, Da Corte’s Duchamp takes several guises in addition to appearing as himself, including as Rrose Sélavy and as the Joker from Batman comics. Each version of Duchamp gallivants through a replica of a Philadelphia Museum of Art gallery that contains his and other artists’ key works of early twentieth-century Modernism. Comically, Duchamp’s signature chess board rests atop the head of Constantin Brancusi’s The Kiss (1916). The artist enlisted his brother, Americo Da Corte, a house painter, to periodically repaint the box in which the film is screened in an homage to John Baldessari, who tapped his own house-painting roots in Six Colorful Inside Jobs (1977). Da Corte the artist and Da Corte the housepainter manifest very different valuations of aesthetic labor. The film is funny and odd, with frequently changing elements, yet the affect of the Duchamp character is hollow, like a mask, with an exaggerated expression that resembles what a pantomime or a drag artist might wear.

Near Da Corte’s art historical gender roleplay, Leidy Churchman’s painting Mountains Walking (2022) filters Claude Monet’s Water Lilies series through a reading of the Zen Buddhist Mountains and Waters Sutra. Both of Churchman’s sources emphasize presence in the here and now. The landscape in three panels is installed on wheeled easels that imply an endlessly mobile configuration; the easels’ claw feet suggest a wildness behind the illusory picturesque surface. In contrast to Da Corte’s performative representation of identity and gender, Churchman’s work proposes a version of transgendered self-construction that is more integrated and simultaneously less stable in its presentation.

Lisa Alvarado, Vibratory Cartography: Nepantla (detail), 2021–22. Acrylic, ink, gouache, canvas, burlap, fringe, polyester, and wood, 82 × 90 in. Courtesy of the artist; Bridget Donahue, New York; LC Queisser, Tbilisi; and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow.

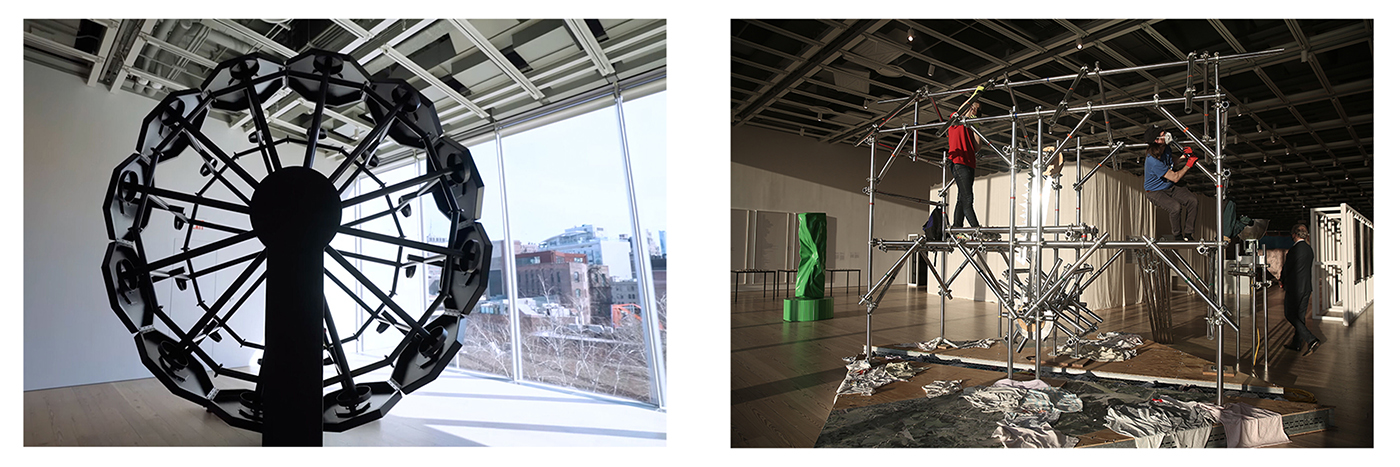

The exhibition establishes a contrast between two moving sculptures, Sable Elyse Smith’s A Clockwork (2021) and Jason Rhoades’s Sutter’s Mill (2000), which are installed on opposite ends of the fifth floor. Smith’s sculpture is a slowly turning wheel assembled from tables and stools repurposed from prison visiting rooms and painted black. Invoking both a Ferris wheel and a millwheel, the installation is a testament to the labor that fuels leisure, sustenance, and incarceration. Sutter’s Mill is a performance in which hired workers assemble and disassemble platforms constructed from components of Rhoades’s sculpture Perfect World (1999). “The installation,” the curators claim of Sutter’s Mill, “brings the conditions of manual working-class labor into dialogue with the United States’ history of wealth accumulation and financial speculation.”8 The work is staffed throughout the exhibition by art handlers—working-class if MFA-credentialed, below-the-line artists, working for minimum wage inside galleries that were built by financial and geographical speculation. The curators continue, “It also symbolizes the constant tension between order and disorder, creation and destruction, that is involved in the process of making art.” Making art may involve surplus labor, but generally speaking, both an outcome and a measure of success are tangible within a studio practice. Cyclical surplus labor is less the province of art than of institutional presentations of art, in which installation mounts and walls are perennially built and torn down; objects go up and come back down; shipments of artworks come in and out. Art handlers and other museum workers are among the 96% of artists who compete for 53% of shows at major museums,9 and they rarely, if ever, have their work shown within the institutions where they work. As this data suggests, Moten and Harney’s undercommons is populated with disenfranchised, surplus academic labor, of whom museum workers—including curators—are a subset.

The mechanism of expansionist development within museum culture that drives speculation on the basis of surplus labor reflects a larger shift toward speculative economies, which, Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, has fueled a boom in prison labor since the 1980s. Gilmore contends that the decline of industries like manufacturing and small-scale agriculture has resulted in making available large sections of land that investors can repurpose into prisons (and other institutions, such as museums, universities, and sports complexes). These operations create the appearance of an economy where there is none, harnessing civic, private, and labor power to create jobs by warehousing people10— convicts, but also audiences, in the spirit of what Hito Steyerl calls “the terror of total Dasein,” which translates as a demand for constant presence in the era of “live art.”11 To connect back to Smith’s massive A Clockwork, the prison system eliminates any pretense to a purpose beyond crisis capitalism; nonetheless the parallel suggests that another reading of the tight spaces upstairs and the open space below could be that of the prison and the yard.

Left: Sable Elyse Smith, A Clockwork, 2021. Aluminum, steel, and motor. Installation view, Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022. Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist; JTT, New York; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Sable Elyse Smith.

Right: Jason Rhoades, Sutter’s Mill, 2000. Polished aluminum pipes, polished aluminum, wood, metal profiles, metal clamps, blue plastic barrels, wood trestle, cleaning rags, clothing, backpacks, construction helmets, lamp, laminated color prints (from Perfect World, 1999). Installation and performance view, Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022. Photo: Paula Court.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s prints and videos, on loan from the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, are set apart from the rest of the open fifth floor by hanging curtains in an effort to create the quiet and contemplative atmosphere that her subtle, intellectual objects demand. Several of Cha’s videos are presented, including Permutations (1976), in which the Korean American artist intercuts shots of her face with the back of her head, and Secret Spill (1974), a twenty-seven-minute video involving a train and other cryptic imagery that is shown on a small monitor inserted between two walls, in a location where it is difficult to stand for more than a minute. Artist books and performance photographs show Cha’s innovative approach to language, the charged racial and sexual politics of her work, and her prescient interest in embodiment.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Permutations, 1976. Film still. 16mm film, black and white, silent; 10 min. Courtesy of the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Archive.

Cha, a groundbreaking conceptual artist working with language and immigrant identity in the 1970s, was sexually assaulted and murdered inside the Puck Building in New York in 1982.12 This crime has eerie resonance in today’s hateful climate, particularly with the recent murder of Christina Yuna Lee on Chrystie Street in Chinatown, in February 2022,13 less than a mile away from where Cha died. Cha’s work is quietly earnest, without the ironic gestures that made some other artists of her era, for example the Pictures Generation, marketable. Her cerebral work feels like tension and conveys the sense of being out of place—feelings that are characteristic of the 1970s immigrant experience, when cultural authenticity and difference were not widely appreciated in the newly arrived. Cha remains intensely relevant and woefully under-recognized outside of the Bay Area, where she studied and emerged as an artist in the 1970s. The absence of a proper gallery installation for her work and the “visible storage” motif in the way her works are displayed are unlike other presentations of artists’ work in the biennial, and they frame the work as an archival find rather than an important artist’s work belatedly acknowledged by a New York museum. I wondered if visitors who didn’t know about her work already would be able to recognize her significance to the history of Asian American feminist art, conceptual language art, and performance art.

Breslin and Edwards include objects with no stated maker and no explanatory wall text: a vial containing “Thomas Edison’s last breath” is attributed to employees of Henry Ford, and an unidentified object that may be made of wood and iron and date back to the colonial period is mounted on a wall in the same sixth-floor gallery, too high to see clearly and without a tombstone label indicating the year, material, and country of origin. Is it an item in the Whitney’s collection with a connection to the slave past, mined from the museum? Is it an object whose maker is no longer known? The curators installed these objects in a darkened space with a sound work by Raven Chacon, creating an intervention that privileges intuition and sensation over visual information. The interrelation between forms in this gallery is evocative because it is mysterious. Elsewhere, the interactions between Chacon’s work and other artworks aren’t as generous to artworks or viewers. Most egregious is the treatment of songs about cultural genocide sung by Indigenous women and documented in a video by Chacon, For Zitkála-Šá, which is part of a body of work for which the artist was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. These songs of resistance, displayed as a multi-channel projection, are periodically drowned out by the sounds of police helicopters bleeding from a work by Alfredo Jaar across the way. One assumes this juxtaposition reflects a desire to recreate the dynamics of protest on the part of the curators, but the effect on this viewer was to reinscribe—rather than comment on—the violence directed against Indigenous Americans and their sovereignty.

Daniel Joseph Martinez, Three Critiques* #3 The Post-Human Manifesto for the Future; On the Origin of Species or E=hνÓ (+) We are here to hold humans accountable for crimes agains humanity OR In the twilight of the empire, in the spider hole where the masters of the earth have gone to ground with their simulacral weapons, reality gives way to a violent Technological Phantasmagoria Celestial Event or Homo Sapiens are the Ultimate Invasive Species on the Earth or MODERNISM has failed us, the EMPIRE is collapsing, humans are MORALLY indefensible or A world between what we know and what we fear or Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is an absurd one Or Homines corruptissimi Condememant quod non intellegunt (detail). Five photographs, 59 1/8 × 73 3/16 × 3 5/8 in. each. Collection of the artist.

Visitors queue and wait to enter Jaar’s space, a dozen at a time, roughly every five minutes. Once inside, we are shown night-vision video footage from a Black Lives Matter protest with marching peaceful people holding signs. Soon, police aggressively kettle the protestors, calling in air support from helicopters that fly closer and closer to the people. Massive fans drive air into the gallery, pummeling viewers with force to mimic the effect of the helicopter blades. Once we have felt the full pressure of the state’s paramilitary subjugation, we are released back into the fifth floor, slightly stunned and deafened (ear plugs are available, but you have to ask for them). For anyone who has experienced state violence, this experience could be retraumatizing. As with Jordan Wolfson’s violent VR installation in the last biennial, the Whitney doesn’t seem too concerned with comforting the afflicted so much as afflicting the comfortable. At this scale of resources, institutions could potentially do more public good if these values were reversed.

Adjacent to this simulation of ongoing neocolonial violence is a disturbing installation of photographs by Daniel Joseph Martinez. The artist who shocked 1993 Whitney Biennial audiences with his declaration “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white” here presents lurid, media-informed, prosthetic distortions of himself suffering facial disfigurement that prompt weak gasps of surprise from a public that is well versed in computer-generated special effects. The extensive title posits that these works address the condition of the “posthuman” to “hold humans accountable for crimes against humanity OR in the twilight of the empire.” Martinez’s distortions are meant to invoke science-fiction archetypes from literature and recent film and television, such as Frankenstein and Westworld, but the use of his own body as performer adds little to the discourse that his sources already engage. Like Jaar, Martinez assumes that museum visitors understand who the “we” are who will “hold humans accountable,”14 with a tone that assumes a clear delineation between the purveyors and the victims of colonization. But when you work in the art world, the good guys and the bad guys are not always so easy to tell apart.

Alfredo Jaar, 06.01.2020 18.39, 2022. Video still. Video projection, sound, and fans; 5:20 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York and Paris.

The aggressively antagonistic artworks of Jaar and Martinez say out loud what Quiet as It’s Kept otherwise keeps quiet, which is that the anticipated audience for this exhibition is one for whom the horrors of the present moment must be made acutely perceptible in order for them to register. In comparison with these works the elegies of pain that resound through works such as James Little’s black-on-black paintings, the textures of which shimmer elegantly; Adam Pendleton’s forthright portrait of Ruby Sales; Chacon’s recordings of Indigenous women performing songs of resistance; Guadalupe Rosales’s luminous nightscapes of Los Angeles sites where people close to her were killed; and Rebecca Belmore’s haunting blanket-wrapped figure surrounded by spent shell casings say more to this viewer about the tragedy of contemporary existence than Jaar’s and Martinez’s more obvious gestures, the inclusion of which suggests that the public must also be slapped and shaken into understanding.

Is this it? On the heels of unprecedented (if reversible) gains in representation and leadership by people of color in museums in the last five years, have we already given up on shifting the values of these institutions toward public access and resigned ourselves to throwing smoke bombs at limousine liberals? Is this what institutions like the Whitney are truly capable of doing best, the cultural conversation they are best equipped to drive? Breslin and Edwards invoke David Hammons with the subtitle of their exhibition. Hammons curated the original Quiet as It’s Kept at Vienna’s Christine König Galerie in 2002. His exhibition featured Ed Clark, Stanley Whitney, and Denyse Thomasos, three African American painters then based in New York. Today, Clark and Whitney are represented by major galleries, such as Hauser and Wirth, Gagosian, and Lisson. Thomasos, the sole woman in the group, remains overlooked enough for her to be considered a “discovery” twenty years later—a decade after her death. While Hammons is not in the biennial himself, his massive sculpture Day’s End (2014–21), which is part of the Whitney’s collection, is prominently installed on the Hudson River directly across from the museum. That skeletal steel structure marks the city’s transformation from the 1970s to now—the conversion of a wild and creative space of outlaws into a monumentalized landscape of luxury. Art that commemorates the passing of a formerly vibrant cultural presence takes on a funereal quality, whereas the biennial is supposed to be about the pulse of the present moment. This suggests that we are still in a period of collective mourning and grief.

Raven Chacon, Three Songs, 2021. Video still. Three-channel video installation, 6:51 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Fighting erasure is exhausting, and perhaps the most honest artwork in the 2022 biennial does not appear in the galleries at all. EJ Hill’s pink monochrome is an intervention into the exhibition’s print catalog. Hill’s immense performative presence has made him a rising star and cast him as an artist who will call out institutions from within—a popular mode of political positioning for institutions that rarely look outward. For the Hammer Museum’s Made in LA 2018, Hill stood on a plinth in the gallery all day every day while the exhibition was open. His durational works of this nature opened doors to his pick of high-profile offers, such as Prospect 5 New Orleans. But the art world doesn’t replenish what it takes from bodies of color. Every gesture Hill has expressed since Made in LA has been one of unbearable lightness underpinned by deep darkness. Moreover, his move here is pragmatic: a catalog intervention is a way to participate without investing time and resources that American museums frequently don’t provide to artists, especially BIPOC ones. Perhaps most importantly, Hill’s gesture, while performative, is explicitly material and minimal in an exhibition that, for the most part, favors allegory and theatrical gestures.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Hill puts a playful spin on the trope of Black conceptual artists painting conceptual art black to please the market (see Pendleton’s Black Dada book of 2017), but Aria Dean makes the point more explicitly with her chroma-key green sculpture Little Island/Gut Punch (2022). The sculpture was designed in a 3D modeling environment to be a monolith, which the artist then ran through a collision simulation. Unlike black, which is fixed and weighted, chroma-key green is both in your face and functionally neutral, since it can easily be rotoscoped into invisibility in the video editing process. Dean’s work formally recalls a work in the Whitney collection—Tony Smith’s Die (1962), which has the relative scale of a human (72 × 72 × 72 inches) rendered as a cube. Dean has elongated, evacuated, exhausted, and impacted the form here. Whereas Cor-Ten steel was the industrial surface that shifted the terms of artistic practice for artists of the 1960s, Dean’s airbrushed green is the color of post-internet creativity as commodity.

Danielle Dean, Long Low Line (Fordland), 2019. Video still. HD video, color, sound; 18:01 min. Collection of the artist; image courtesy of the artist; 47 Canal, New York; and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles.

This biennial includes more digitally rendered video art than prior iterations, reflecting the increasing availability of technology that allows artists to visualize and model an idea without having to make a physical artwork. Video game aesthetics inform works by Jacky Connolly, Danielle Dean, and Andrew Roberts, all installed on the fifth floor. The decision to show video animations in the large open space rather than in the closed cubes upstairs is a risky one that ultimately adds to the carnival-like atmosphere, making prolonged viewing difficult and creating ample light and sound conflicts. Here, as in every museum exhibition, the unsung heroes are the installation team who attempted to give the curators and artists what they wanted, despite impractical parameters.

Kandis Williams, Death of A, 2021. Video still. Four-channel video installation, color, sound, 26:51 min. Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán.

Quiet as It’s Kept is a thoughtful exhibition with many more worthy inclusions than I have addressed here. As a museum survey, it has gravitas, it’s clever, and it makes compelling use of the architecture with its contrasting exhibition dynamics across the two main floors. It’s not very cohesive—I still can’t explain how the curators’ inclusion of a GAN-generated, evolving LED artwork and paintings on aluminum by WangShui and the machine vision installation by Na Mira fit their curatorial thesis. But each work is deserving of inclusion on its merits, and Mira’s work includes a ritual marking the site of Cha’s 1982 murder, which connects with Cha’s work on the floor below. For my part, I wanted a more in-depth discussion of how broad parodic gestures, such as Andrew Roberts’s digital zombies and disembodied forearm bearing a tattoo of the Amazon.com logo might conceptually integrate with paintings on teepee canvas by Linklater or Awilda Sterling-Duprey’s vibrant dance-paintings, which the artist created onsite. Kandis Williams’s work best embodies the aesthetic of the exhibition, with her cut-up zines of philosophy and pop culture for Cassandra Press. Several of the biennial’s motifs can be seen in her four-channel video installation Death of A (2022), including performance art translations of classic American literature, footage culled from the US military-industrial complex, and testimonials of the Black American experience, which turn out to be from Arthur Miller’s play, Death of a Salesman. In Williams’s multi-channel installation, a nonstop non sequitur of capitalist media and midcentury saber-rattling plays on the left two screens, while a Black cast enacts the rigid gender roles of Miller’s 1950s America on the two screens on the right. As with the biennial as a whole, the implications of the re-framings and re-cuttings in Williams’s work are underdeveloped.

Jane Dickson, 99¢ Dreams, 2020. Acrylic on linen, 39 × 73 in. Collection of the artist.

A surprising and satisfying approach to the archival impulse that runs through this biennial can be found in Jane Dickson’s quirky paintings of commercial storefronts. Made from an archive of photos she found in the 1980s, when she was living and working near Times Square, these images show a less sanitized Manhattan but also a distinctive and haunting beauty that has since been lost. “Everyone lives in a double helix of then and now,” Dickson states. “Now is mostly unrecognizable as it’s unfolding.”15 Abandoned by the Federal government, New York in the 1980s was lawless and, in many ways, a crucible of culture that is hard to replicate under today’s high-pressure conditions.

Dickson’s rear view seems like a fitting one to end on in considering this cacophonous, overstuffed biennial, through which another viewer could find a completely different throughline. Breslin and Edwards, with their firmly binaristic approach (closed/open, dark/light), which mirrors the dualistic pairing of their identities (male/female, Black/white), seem at every step to be constructing a grand narrative but not always revealing their intentions. Ultimately, both the artists and the curators are framed within a discourse of what is manageable—emotions, logistics, labor, materials—which feels fitting if lacking in ambition for a biennial born of our era of poorly managed crises.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and cultural organizer based in Los Angeles. She is the author of Decolonizing Culture (2017) and a member of the editorial board of X-TRA.