And the cuckoo is cuckooing, the magpies are chattering, roes are running. Will they reproduce—who knows? One morning I looked out in the garden, the boars were digging. They were wild. You can resettle people, but the elk and the boar, you can’t. And water doesn’t listen to borders, it goes along the earth, and under the earth.

—Svetlana Alexievich, Voices of Chernobyl , 19971

This brief fragment comes from Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich’s account of a nuclearized landscape: the exclusion zone created around the area in Ukraine where an atomic catastrophe wreaked havoc in April 1986. Alexievich’s book is an exhaustive and haunting collection of memories from people who experienced the devastating accident and its aftermaths. Yet no dramatic image or feeling is delivered in this particular passage. Humbly, the witness describes their home garden through the trope of a nature that . . . goes on. The birds are chirping, the deer are loping—the animal world continues its course without the visible presence of humans but with the invisible presence of toxicity. Following the nuclear meltdown, the disaster-stricken human populations of Chernobyl were relocated to areas far removed from the reactors. The question of how to deal with disaster-stricken animals was more complex.2

My interest in animals, especially boars and horses, populating exclusion zones following nuclear accidents stems from an encounter with the work of literary scholar Alison Sperling, whom I interviewed along with Ruby de Vos.3 The depiction of the animal world as oblivious of borders in Alexievich’s succinct yet forceful statement got me thinking. The elk and the boar indeed cannot be resettled because they have their own established paths in the forest and their own social relations that help shape the natural environments they live in and move through. Essentially, the elk and the boar convey a sort of stubbornness by staying in the zone that humans have left and encourage us to consider radioactivity’s notoriously uncontainable nature. Through their everyday movements in the forest and the deserted city, the animals challenged the wishful thinking of the then-Soviet Ukrainian state regarding toxic containment.

The French artist Elsa Brès has also been looking at wild boars as border transgressors, though in a different geographical context. I first came across her film Notes for Les Sanglières (2021) on my screen during the pandemic, while scrolling forlornly through Transmediale’s edition online.4 While my body and visual field were restricted to the indoors, her images of boars rambling free where humans were prevented from walking appeared emancipatory, a bit like my own walks in the locked-down city where I lived at the time; walks that felt like brief suspensions of an unceasing lockdown enclosure. In its depiction of intruding boars, her piece unexpectedly resonated with the impossibility articulated in Alexievich’s account of Chernobyl’s more-than-human life: its animals, plants, insects.5

More-Than-Human Filmmaking

Brès’s short film Notes for Les Sanglières is a preparatory sketch for a longer film in the making that the artist intends to release in the spring of 2024. Both films focus on the boar, an animal that has enjoyed many media appearances as of late through videos and photographs. From bustling cities—parks in Berlin, Roman suburbs, even the streets of Hong Kong—to barren exclusion zones around sites of nuclear disasters, packs of boars are routinely depicted as unwanted interlopers: peeping into trash bins, looting abandoned homes, attacking people on beaches. Such incidents have led to them being classified, in many places in Europe, as an invasive species. Notes for Les Sanglières suggests a possible alliance between boars and humans, troubling narratives of human exceptionalism and forging an image of how humans could live socially, even politically, with wild pigs. The title riffs on an attempt toward redress, a desire for change: les sanglières means “female boars” in French, feminizing the male term les sangliers, yet the term technically does not exist in the French language. The word sanglières is also inspired by the title of Monique Wittig’s 1969 feminist novel Les Guérillères, which imagines an attack on androcentric language and bodies by a community of women. Translated excerpts of the novel appear throughout the film. Brès’s own motives for creating new lexical entities start from the purely scientific: female boars lead their wild boar packs.

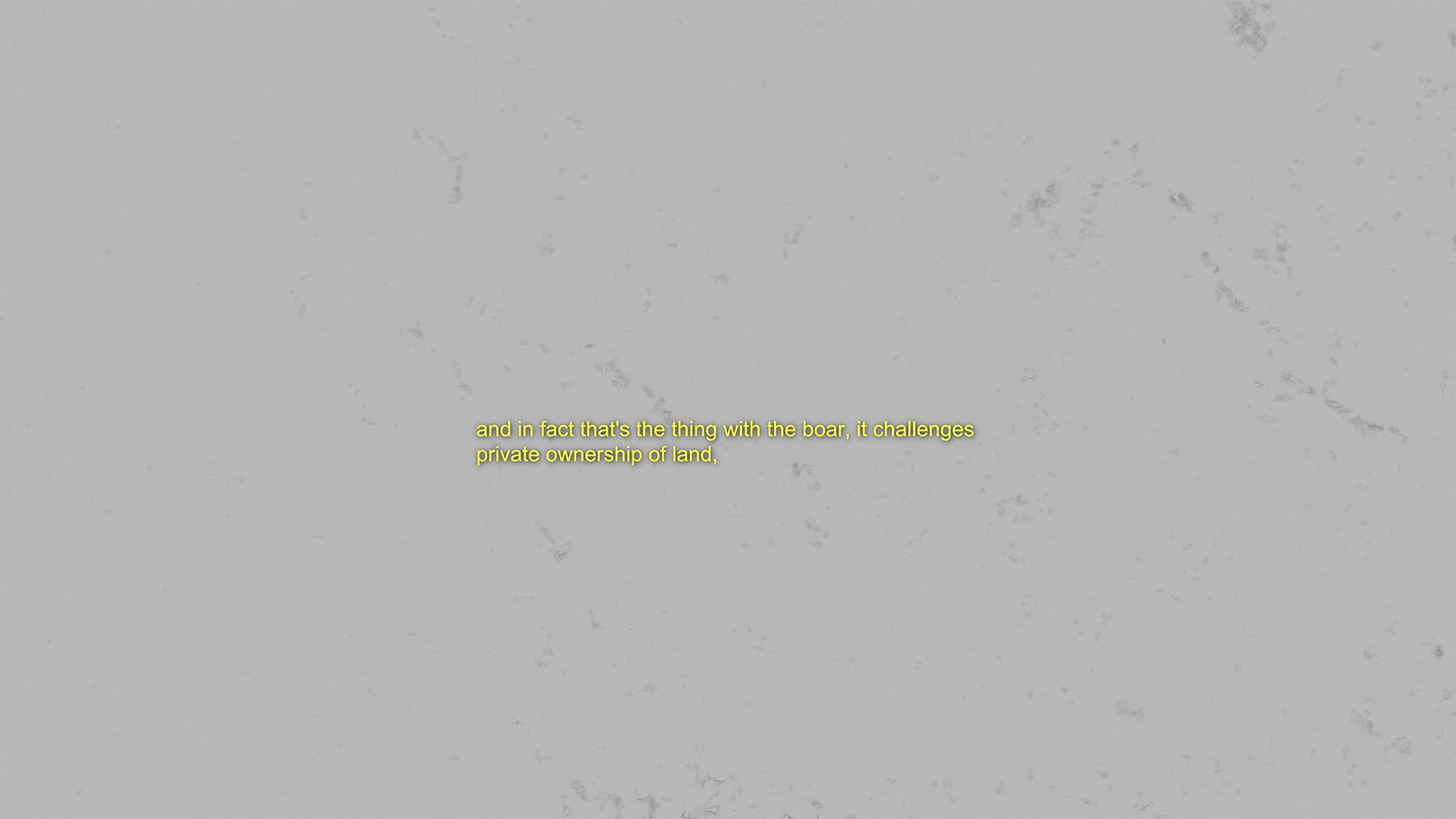

Brès’s video is enthralled by the more-than-human protagonist it obliquely depicts. To pursue this improbable subject, Brès works her way through different representations and significations of the wild boar, including text overlaid on image, animal sounds, and conversational dialogue layered onto images of maps mixed with grainy infrared shots of boars in a forest. Yet the artist retains a certain distance from the animal itself. The animal scenes are set in the Cévennes, a rural mountainous region in the south of France where the artist lives and where wild boar invasions have wreaked havoc in recent years. The film starts on a non-image—a blank screen. Someone (human? animal?) can be heard walking over dry vegetation and making rasping sounds with each step. Birds are chirping, and a male voice slowly, shyly emerges. A few minutes in, yellow letters pop up on the blank screen, transcribing a dialogue between the artist and Paul Guillibert, an environmental philosopher, in which the latter tenaciously contends that certain species, particularly boars, “refuse to be controlled by private property.” These initial minutes make us witnesses to a dialogue about the boar as a figure of invasion, of savagery, of intrusion into private property. Society draws strict confines to keep the interlopers out, from concrete to metal (and even electric) fences. And this sense of exclusion is precisely where the central concern for Brès’s bigger film project hails from: Might we position ourselves on the boars’ side? On the side of the excluded?

Elsa Brès, Notes for les Sanglières, 2021. Video still. Single-channel video, 17 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Humans (Not) Looking at Boars

Filmmaking is a practice modeled on the human gaze, and this is why being on the boars’ side surely requires novel cinematographic methods, a shifting of perspective. Fittingly, the visual perspective is mostly forestalled throughout the video. Following the dialogue with Guillibert, Notes for Les Sanglières gives us more sound. Faint landforms, reminiscent of dense foliage, are barely visible on the white-grayish screen. A plurality of sensory presences manifest as we hear the gasping breaths of the walker entangled with an animal’s breathing, presumably a boar’s. Five minutes in, the screen still shows a blurry, non-decipherable blankness. It speaks not to voyeurs but rather to listeners to a yet-unknown creature that we impatiently wait to see. The forestalling of cinematic vision could be read through gendered readings of spectatorship, whereby the camera’s gaze voyeuristically turns the depicted subject into an object of pleasure, creating a clear split between the active (usually male) gaze and the passive (usually female) subject of representation. This is precisely what does not happen in the film: boars are not mere objects of representation but are approached as creatures with agency, their own thoughts and desires (and who, as we will see, interfere with the very medium of representation). Understood in feminist terms, delaying delivery of an image of the feral protagonist reads like a refusal to claim or seize the filmic subject so as to propose ways of relating to it that don’t involve domination.

Speaking of animal observation in critical ethology work, the Belgian philosopher Vinciane Despret admonishes us for desiring to take the animal’s perspective. “It involves a dangerous flirtation with anthropomorphism,” says Despret. “Is one putting himself in the animal’s shoes or, on the contrary, does one actually put the animal in human shoes?”6 In other words, is it even possible to apprehend the boar without objectifying or humanizing it? The video’s reluctant, nonvisual introductory minutes sketch another possible mode of relating to animals. Through the merged sounds of human and animal breaths, Brès enacts empathy not through “experiencing with one’s own body what the other experiences” but rather by “creating the possibilities of an embodied communication,” as Despret puts it.7 Brès’s sonic montage points to a sensible and indirect, rather than disembodied and positivist, approach to animals. Importantly, such embodied communication does not, as Notes pour Les Sanglières shows us, always entail direct bodily presence.

The graphically arresting images of maps that come next devise another ancillary way of fathoming the animal. The artist created these maps, which fan out in a fluorescent palette of purples, blues, and reds, in consultation with a data scientist specializing in forest inventory and geomatics. The multicolored relief images are essentially representations of the boars’ movements through the forest, taking into account various parameters such as distance to water sources.

Connivéncia, installation view, La Loge, Brussels, Belgium, September 6–December 3, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and La Loge. Photo: Lola Pertsowsky.

When the artist presents the video in an exhibition, like the one at Transmediale in Berlin or more recently in the artist’s solo show at La Loge in Brussels (Connivéncia, September 6–December 3, 2023), the display apparatuses migrate. While the main video is projected onto a wall, a screen on the floor, facing the ceiling, sporadically beams maps. This separation stages a multi-windowed cinematic experience that ontologically sets cartographic tracking in vertical perspective, apart from auditory perception. It results in a viewing experience that is fractured, almost dysfunctional: the verticalization of the screen forces a fleeting gaze at the maps. Brès’s background as an architect shows here. The artist has long been interested in different ways of making and claiming space, yet is cognizant that cartographic renderings of the world are, inadvertently, tacit representations of a gaze that instrumentalizes that same world.

These abstracted images of space retrace the boars’ paths as well as the ways the packs design their passages in the Cévennes forests by rendering what the animal leaves in the landscape. The boars are approached via their footprints—via their traces—rather than their image. Proximity to the animal, but not direct encounter, becomes a filmic tool. Tracking here is a common strategy redirected: it is deployed not to capture the animal but rather in an attempt to understand it—how it makes its way across the shared space of the forest near Brès’s home, how it uses it, and how human intervention in the forest might disturb it. Brès’s deployment of cartographic strategies of tracking to produce evidence recalls Forensic Architecture’s approach to violence. In the case of Forensic Architecture, the evidence they produce is so exacting it can even enter courtrooms. Brès’s tracking methods, however, yield only indirect evidence, and not of violence but of a more-than-human lifeway.

Brès’s indirect filmic encounters with the boars summon a sense of humility, recalling the ecofeminist philosopher Val Plumwood’s chilling account of becoming prey. While canoeing in Australia’s Northern Territory in 1985, Plumwood was almost eaten alive by a crocodile. This experience became for her an orienting force for new thinking.8 In coming too close to the animal, she herself became an object. A crocodile death-roll, an admittedly violent incident of self-objectification, led her to recognize that we, as humans, not only eat; we are also eaten. Understanding ourselves as fundamentally edible might help us to recognize at the core of our relationship to the natural world our own vulnerability as a species—something Western views on nature try to forget.

Boars Looking at Humans

Elsa Brès, Notes for les Sanglières, 2021. Video still. Single-channel video, 17 min. Courtesy of the artist.

In Notes for Les Sanglières, boars eventually do make brief appearances. Interspersed with prose from Wittig’s Les Guérillères—for instance “they refuse to pronounce the nouns of possession and non-possession”—grainy, black-and-white shots slowly reveal the animal. Eyes seeming to glow in the dark, they appear unhurriedly in the dark space of the forest. The artist had installed a motion-activated, thermal video camera, like those used by hunters, for a few days at that point. Initially developed for surveillance and military operations, thermal cameras register heat (not visible light, like a regular camera) and then translate the data into imagery.

Elsa Brès, Notes for les Sanglières, 2021. Video still. Single-channel video, 17 min. Courtesy of the artist.

The boars seem to notice the camera, to be aware of this technological infiltration of their habitual trail, but they do not interact with it. At least not at first. For a few minutes, they inquisitively whirl around it. At some point, one of them gazes straight into the lens. Its glare is uncannily reminiscent of the filmic breakage of the fourth wall, as when Ingmar Bergman’s Monika (Summer with Monika, 1953) looked at me in my early twenties in the student cinema in Athens, and the space of film and the space of the movie theater briefly converged. What are we to do with that eerie animal look? What exactly is attacked in that Brechtian encounter between human as viewer and nonhuman animal as actor? The boar’s piercing gaze meets mine, asserting its agency. It reminds me of a unity that I know is impossible yet whose very possibility is unexpectedly appealing. By looking at me, the boar is afforded a status usually reserved for humans, and it is that troubling realization that casts doubt upon my own voyeurism. Brès keeps with the contradictions of her technical apparatus—it is, after all, a hunting camera—and reminds us that humans may look at animals, and animals may return the gaze. Like Plumwood’s reciprocity: I eat, and I am also eaten. I look, and I am also looked at.

Ingmar Bergman, Summer with Monika, 1953. Film still, 35mm, 96 min.

Despite its force, the look is brief. Boars have poor eyesight and rely heavily on smell to orient themselves. When one of them comes a bit too close to the camera to smell it, the image clouds into tints of white and gray. Sound becomes prevalent again, the animal retreating from sight to reinhabit the terrain of invisibility—what we see is a bleary screen. What we hear, however, is (presumably) an act of revenge: suddenly, one of them decides to eat the camera. The boar’s bodily acoustics are enmeshed in a sonic montage with a blaring soundtrack by Méryll Ampe, a longtime collaborator of Brès. Ampe’s soundscape in this scene is palpable, at once carnal and wild, stark and melodic, the camera throbbing in the animal’s mouth. The saliva sound is the sound of impurity whereby hunting technology cements in the animal’s body and boundaries between nature and culture collapse.

In brief, the camera, that tool of representation and domination, is forced into an embodied perspective. It becomes prey. By dismantling the device on which the artist relied to approach them, the boars turned an object of representation into an edible proposition, and in that, Notes for Les Sanglières becomes a film and a non-film, both scopic and anti-scopic, looking at animals but also rejecting that very possibility. Brès taps at the heart of that coming together between human and nonhuman animal, gesturing, perhaps, not to a unity but to an equality of sorts. If we are to think of a possible alliance between human and nonhuman animals, then the look has to go both ways. It might require an uneasy confrontation.

Swiny Encounters

Brès explained to me in conversation that one impetus for the work is her sense of unease in front of paradisiac painterly scenes of boar hunts, which usually display slaughtered prey. Such cherished tableaux of an untamed nature stake a claim to the land by proffering a view of nature as a treasure that some have entitled access to while others, human and more-than-human, are left out or forcibly removed. In some ways, the archetypal representations of boars have evolved into their present-day media depictions as intruders rummaging through garbage. Long considered the dirtiest animals in Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions, pigs are the incarnate of abjection, in Julia Kristeva’s sense of disturbing identities and rules and ignoring humanly established boundaries.9

Brès is not alone in her wild bovine engagements; other art of recent decades has encouraged critical reconsiderations of pigs and other “dirty” critters. In the 1990s, Rosemarie Trockel and Carsten Höller created Ein Haus für Schweine und Menschen (A House for Pigs and People, 1997), a modernist structure that housed a pig family in one half and human visitors in the other. Visitors could see the pigs but not hear, touch, or smell them; all senses but sight were bracketed. More recently, the curatorial collective Don’t Follow the Wind has been initiating collaborations with the more-than-human residents of the irradiated Fukushima exclusion zone, including boars. Similar to Notes for Les Sanglières, the collective uses thermal cameras to explore how the boars adapt to this new environment and what that might entail for future cohabitation with returning residents. Julian Charrière and Julius von Bismarck, in their Objects in Mirror Might Be Closer Than They Appear (2016), attempt to see the world through the eyes of a horse in the Chernobyl exclusion zone by installing a camera in front of its eye. The resulting video of the horse’s world—a dizzying mirror image of the zone on the animal’s pupil—is also a spinning take on our contaminated world. Seeing with and through animals will be vertiginous. These projects, and many others, offer pointers for the elaboration of the impossible. As with Brès, it requires venturing (and failing) to see through the animal’s eyes, and thus testing the limits of sight itself. As with Brès, it’s about the exploration of boundary conditions: “toxic zones,” which represent a vain pursuit of purity and strict divisions between human and more-than-human realms. Brès dares to pose the perennial question: What if those lines were crossed?

Elsa Brès, Les Sanglières, forthcoming, 2024. Film still, 75 min. © the artist. Courtesy of Elinka films.

The last scene in Notes for Les Sanglières is a shaky and silent shot. A pack of boars bounds across a country road. A sense of liberation is in the air; but also indifference. The boars are not looking back, or at us anymore. Just forward. The longer, final film, to be released in spring 2024, intersperses this scene with an emancipatory fiction of women who, through action and animated footage, ally with boars in an imaginary revolution. Women and boars march together in a dim, nocturnal forest, calmly but with fervor, like in a collective, reclaiming space. Brès collaborated with local women for this part of the film. These nonprofessional actors linger in ambiguity and resist assimilation. Quietly, human and more-than-human bodies come together, resisting boundaries or control over each other’s bodies or any separateness from the world. Yet Notes for Les Sanglières’ concluding, solo take on the animal’s indifference toward us, the viewers, strikes at the heart of the artist’s interrogation of anthropocentrism. The boars are, after all, not returning the gaze. They embody a resistance to human exceptionalism, spatial containment, and bodily control, just like the wild boars of Chernobyl’s exclusion zone. x

Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou is an art historian and research fellow and lecturer at VU University, Amsterdam. She is currently working on her first book, which tells a transnational history of uranium through art and activism.