Dust carries within it multiple places and times. It is “a disguised unity of minute contagions and pollutants” from “milieus so distant from one another that they can operate for each other only as outsiders.”1 Even as dust is the return to oneness with God (from dust to dust), dust is always legion; it is a host of other bodies that were once under this possessive, coherent illusion of your body, your self.

In Miljohn Ruperto and Rini Yun Keagy’s 45-minute video Ordinal (SW/ NE) (2017), which I first encountered in Ruperto’s Geomancies exhibition at REDCAT, we see aerial views of Central California’s parched and devastated environment and our alienation from it, as shots cut between drought-stricken landscapes and suburban homes with swimming pools and manicured lawns. In the opening intertitles, Ruperto and Keagy connect this contemporary landscape to the history of the American Dust Bowl, a site that witnessed a series of dust storms due to the destruction of the Midwestern agrarian landscape in the 1930s from overfarming, overgrazing, and subsequent droughts. During the “dirty thirties,” the depleted soil from the Midwest formed vast, billowing clouds of dust that were seen as far as the East Coast and were known as “black blizzards” or “black rollers.” The invocation of blackness or darkness for that which is foreboding, evil, ominous, and contaminating is an association that is racialized, whether or not it is acknowledged as such. In their film, Ruperto and Keagy employ many such racialized assemblages of the demonic, including dark stormy clouds, Pazuzu (an Assyrian demon), a black spinning square, and a possessed, dancing black body. But they do so in order to destabilize the logic that links blackness to evil and non-being.

The film begins with a black sprinkler head emerging from a well-watered, suburban lawn, lit by the artificial sun of a garage security light. The banality of the black sprinkler head becomes eerie and at the same time absurd, in its reference to the mysterious black monoliths in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Like Kubrick’s monoliths, which arguably represent extraterrestrial consciousness in a non-anthromorphic form—beings so evolved they are “immortal machine entities” of “pure energy and spirit” with “limitless capabilities and ungraspable intelligence,”2 the demonic in Ordinal (SW/NE) is also often represented by abstract black shapes. Like global warming or any other hyperobject,”3 the demonic in Ordinal (SW/NE) is that which cannot be encompassed and fully understood. The demon appears only rarely in human-like form, as Pazuzu or the possessed dancer, but is present throughout the film as a collection of effects—the devastated environment, a chronic and persistent cough, the sick baby—that withdraw from any totalizing understanding.

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

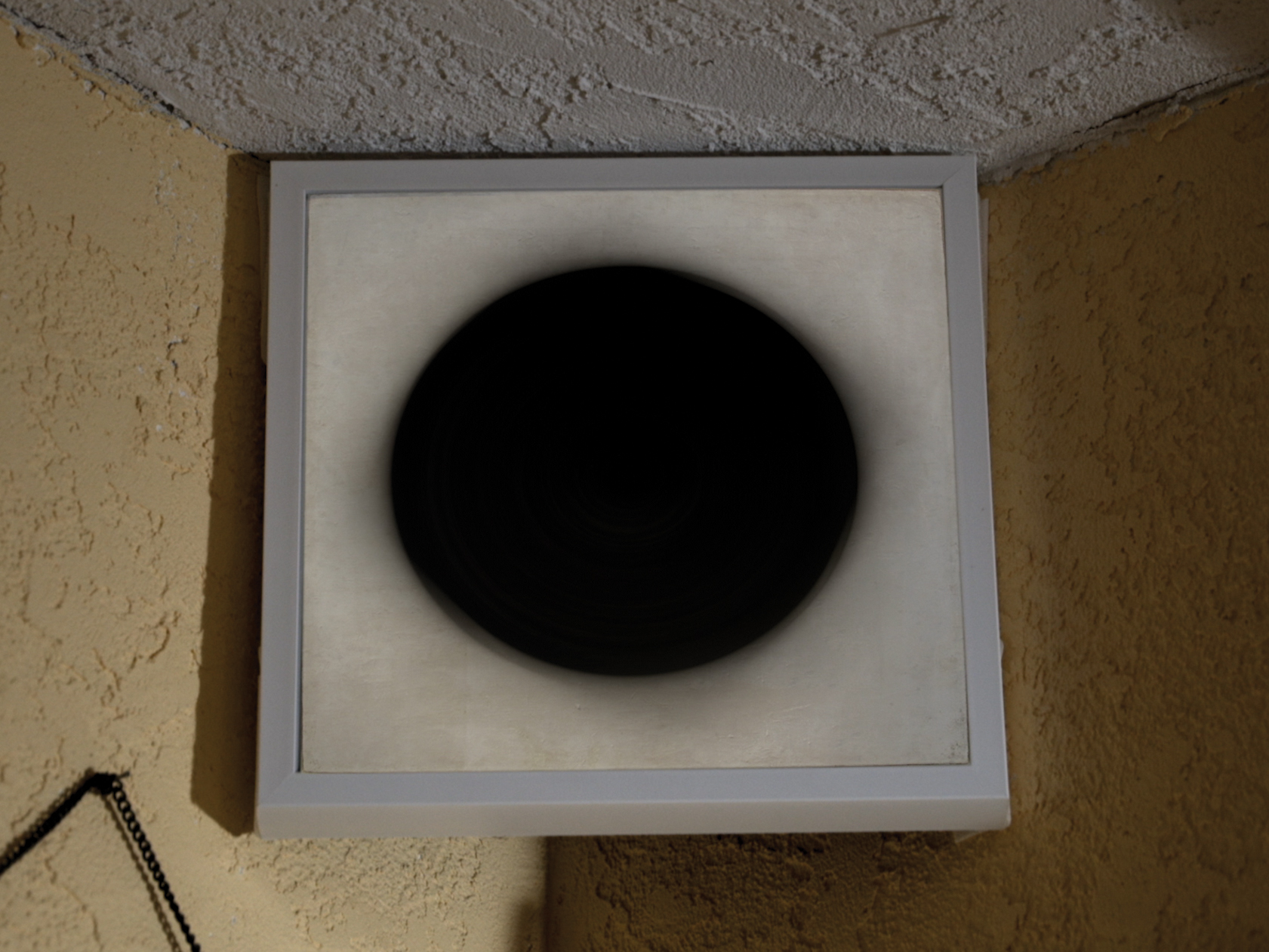

Philosopher Eugene Thacker uses the phrase “horror of philosophy” to address the existential dread and void that yawns when “the answer to the philosophical question ‘why is there something rather than nothing?’ could quite possibly result in the response ‘there is nothing,’” rendering philosophy’s endeavor futile and absurd.4 For Thacker, this horror of nothing has a tradition of being described by its blackness, its darkness, its negation of whiteness and light. Thacker uses descriptions of black sentient oil, black metal music, and black abstract artworks to show how darkness points to a limit that brings us “to a philosophical dyad…the distinction between presence and absence, being and non-being. Darkness is at once something negative and yet, presenting itself as such, is also something positive.”5 In these philosophical dyads of good/evil, human/inhuman, light/dark, and white/black, we see the seeds of racialized horror. Blackness becomes the visible mark of the impossible-to-imagine ontological opposite, but it seems separate from issues of race or black bodies because it is represented through abstraction, often appearing as an amorphous cloud or a “self-negating form of representation,” such as a primary shape. Thacker writes about the black square as an early representation of cosmic nothingness, first with Robert Fludd’s Utriusque Cosmi, of 1617, and later with Kazimir Malevich, in 1915: “Black is less a color and more the withdrawal of every relation between self and world.”6

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

Arthur Jafa, writing about European Surrealists and Cubists encountering traditional African artifacts, explains how such artifacts were seen as stylized and abstract because of “the inconceivability of the black body to the white imagination.” Cubism arose as a European response to the way African art and the radical ontology these objects embodied broke open Western conceptions of space and time. But this rupture to the white imagination could not be followed out politically or socially; it could not actually tear the fabric of European hegemony beyond a nod to cultural relativism or, worse, as exemplar of a primitive, symbolic state. African artworks that challenged a European conception of reality were seen as artistic interpretations, as “creative distortions,” as fetishes. In their difficulty in grappling with the equal reality of beings radically different from them, both physically and culturally, in their conception and representation of bodies, time, and space, Europeans turned to abstraction, claiming that these African objects did not refer to a real “radically different (alien) ontology” but rather to an earlier symbolic state. This aestheticization allowed for the preservation of “Eurocentric belief in itself as the defining model of humanity. This, in turn, has provoked the ongoing struggle against the acceptance of the ‘other,’ and its full humanity.”7

In “Necropolitics,” Achille Mbembe argues that some subjects are alienated from full humanity. He distinguishes between those who possess zoe, mere biological life, which aligns them in proximity with death and instrumentalization, and bios, those who possess full human existence. Mbembe and other scholars—including Paul Gilroy and Alexander Weheliye—have linked this necropolitical view of “bare life” (the wounded, expendable destroyed remainder of political bios that lies in a “zone of indistinction and continuous transition between man and beast,” between zoe and bios)8 to race. Mbembe traces the genesis of “bare life” not to the Nazi death camp, as the philosopher Giorgio Agamben does, but to the plantation and the colony. It is in the plantation and the colony where a philosophical understanding of the void/demonic/ inhuman as blackness becomes attached to flesh. The phenotypical darkness of certain bodies marks and justifies their lesser humanity, their closeness to supernatural evil, the demonic, and the subhuman beast. The darkness, philosophically and as attached to human bodies, exists merely to foreground, through contrast, the light—the fully human white subject.

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

In all his writings on darkness and the inhuman, Thacker is in collusion with Agamben in the avoidance (or transcendence—“the biopolitics of racism so to speak transcends race”9) of the language of race through examples that abstract the use of blackness from the human body. One example Thacker uses is the sci-fi writings of H. P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft’s writing is important to the film Ordinal (SW/NE) as well, which makes reference to the Necronomicon, the imaginary book that appears in Lovecraft’s writing. Graham Harman, another philosopher influential on Ruperto’s thought, speculates that Lovecraft’s success in portraying the inhuman comes not from a detailed precise description but rather its opposite, a “vertical” or “allusive aspect” in his writing that creates a gap “between an ungraspable thing and the vaguely relevant descriptions that the narrator is able to attempt.”10 Lovecraft, like Thacker, also uses metaphors of darkness to describe the inhuman, the void, but in the context of the overtly racist language in Lovecraft’s writings, blackness cannot maintain the illusion of neutral abstraction.11

The demonic can only be seen through blackness, through obfuscation, through oblique, peripheral attention. Ordinal (SW/NE) layers various histories and stories hypnotically, and seemingly disparate references to The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Assyrian demons, and valley fever all circle around a fleeting and ungraspable horror. The references point across each other, creating oblique lines of attention, allowing for flickering glimpses of what usually remains beyond understanding. This methodology to locate the demonic is evident in the layout of the works in Ruperto’s exhibition Geomancies, where Ordinal (SW/NE) is one of five works on display and the only work made in collaboration. In the gallery, the entrance to the room where Ordinal (SW/NE) is projected points southwest and is directly across from Demonology: Pazuzu (2017). Ruperto’s lenticular print of the blackclothed demon Pazuzu is a visual “trick of the eye” that uses low-brow reproduction techniques to echo a stereoscopic illusion of three-dimensionality. From different angles, the lenticular print shifts slightly, echoing the parallax shift in your left and right eye, moving the demon into an illusionistic space shared with our bodies. With this momentary entering into our space, it operates as a memento mori, like the hidden, anamorphic skull in Hans Holbein the Younger’s famous painting The Ambassadors (1533). Originally hung in a stairwell, Holbein’s painting could only be seen in passing, out of the peripheral vision of the person descending or ascending the stairs—a sobering, daily reminder of death. Because Demonology: Pazuzu is placed in the narrow space between the wall of the gallery and the room containing the video Ordinal (SW/NE), one cannot ever see the lenticular print at appropriate art-viewing distance. Instead, like the Holbein skull, viewers only see it out of the sides of their eyes, while entering or exiting the video room, brushed with death.

In the eastern corner of Geomancies is a short video that also spatializes the oblique. Driving South at Sunset. The Camera Faces East (2007) depicts a South Asian woman driving south on Interstate 5 near San Diego. In Geomancies, Ruperto recontextualizes this older work within the contemporary political landscape, at a time when the United States / Mexico border is particularly fraught with demonizing rhetoric. As the woman drives, the camera captures her image from an oblique angle, and she sings a phrase from a country song intermittently under her breath, “You were always on my mind.” The viewer echoes the cameraperson’s axis of attention, which points east, while the driver focuses her attention south, creating an X between lines of sight, a target that is constantly shifting because it was filmed as the car moved steadily closer to the politically charged, southern national border. The oblique angles and lines of sight explored in this short work point to the exhibition’s formal uses of the X in other works, such as its appearance in the video Ordinal (SW/NE), where the X is referenced in the shape of the demon Pazuzu’s wings and is the name of the invisible, female character whom we do not see but who is marked with sickness and contamination. We also see the main character sitting below a poster with the symbol X as he struggles through fits of coughing. Both videos use X as a formal symbol and as recurrent intersection of the gaze to ask larger questions of the shiftiness and uncertainty in marking what or whom is considered demonic, monstrous, contaminating, and possessing.

Miljohn Ruperto, Driving South at Sunset. The Camera Faces East, 2007. Video still. Digital video, 15:20 min. Courtesy of the artist.

But if the X marks the impossibility of pinning evil to one fixed site or body, the dust that swirls around in Ordinal (SW/NE) reiterates this failure. Dust complicates philosophical dyads of good/evil, self/other, and light/dark, which are predicated on clear boundaries between who is stranger and who is kin, who has a legal right to be within a nation and who does not, and who is designated for death and who for life. Reza Negarestani writes, “The release of these multiplicities disguised as one within each dust particle is equal to the arrival of the alien not from without but from within.”12 In its fragmentation and dispersal, dust holds a multiplicity of geographies and histories; it blows across the boundaries of nations and property lines, including the propertied sense of one’s self as an individual discreet from one’s environment. The dust in Ordinal (SW/NE) complicates this blurring of the boundaries as dust is breathed in and takes on a life of its own.

The dust of the Central California Valley carries within it living fungal spores, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii, which cause valley fever, coccidioidomycosis, or “cocci” for short. Valley fever causes respiratory infections, tiredness, fever, cough, skin lesions, and muscle and joint pain. “In the nineteen-fifties, both the U.S. and the Russians had bio-warfare programs using cocci,” said scientist John Galgiani in a 2014 interview with The New Yorker.13 The history of biological warfare extends from the US government’s purposeful dissemination of small-pox ridden blankets as “gifts” to Native Americans to the weaponization of inhalational Anthrax, a powdered form of living bacterial spores. But biological warfare can be slippery to trace—accountability can be denied, weaponized biological agents escape standardization, and purposeful contagion cannot always be contained to the intended victims. Galgiani explains that cocci spores were not easy to control because they relied “on air currents to disperse them, and it was difficult to use the vector precisely, so it fell out of favor. But terrorists don’t care about that stuff—all they care about is perception. A single cell can cause disease, and you can genetically modify it to make it more powerful.”14 The weaponization of living beings finds expression in terrorism, whether in the use of one’s own body (suicide bomber) or through other living bodies (anthrax). Like the fungal or bacterial spores that can parasitically lodge and grow within our bodies, taking over our will and health from the inside out, the terrorist, too, is spoken of as being already within our national borders. A threat from within must be surveilled within the national body, marked and rooted out.

Valley fever operates as a spectral character in Keagy and Ruperto’s film. Invisible but present through menace, it reminds us of its power through the persistent asthmatic cough of one character and repeated scenes of possibly contaminated engulfing dust storms. From the lungs, valley fever can spread through the blood to the spine and brain, sometimes resulting in osteomyelitis, meningitis, and death. This is the fever’s most damaging form—disseminated coccidioidomycosis—where the fungus spreads all over the person’s body, and this specific fatal form disproportionately affects Filipinos and African-Americans.15 Those who work with disturbed soil or spend a lot of time outside in dusty environments are particularly susceptible—migrant farm workers, construction workers, oil field workers, and prisoners.16 During the internment of Japanese-Americans in camps in Central California and Arizona, many of those interred left with lifelong health issues related to this fungi. “For African-American and Filipino prisoners, and those with suppressed immune systems due to HIV or diabetes, incarceration in the endemic area can be a death sentence. Between 2006 and 2011, thirty-six prisoners died from cocci, twenty-five of them black.”17

In Ordinal (SW/NE), two gloved hands carefully examine Sam Chase’s historical photograph of a 1977 dust storm taken from above Weedpatch, a Central Californian camp in which the FSA housed the influx of migrant workers from the Midwest. The image is subtly animated to depict the dust storm slowly advancing in an incessant loop, which destabilizes the photograph’s function as material from a historical archive. The film’s primary narrator, a female character named X in the script, tells us the photo is taken from a height of 5000 feet. (According to Omer Fast’s video 5000 feet is the Best (2011), that height is ideal for military drones.)18 The photo also appears as an individual work in Geomancies. Re-animating “Valley Turbulence” by Sam Chase (2016) is a sculptural “lightbox” with the same seemingly still illuminated image that is actually a gif-like animation. But in this sculpture, the looping image takes on the weighty proportions of the large wooden cube it is housed within, a cube that references the Minimalist sculptures of Donald Judd and Tony Smith and, by extension, the human body. But here the square, the cube that stands in for the body, is obscured by the perpetual moving dust of its image, which is constantly, ineffectively surveilled from above.

Miljohn Ruperto, Re-animating “Valley Turbulence” by Sam Chase, 2016. Installation view, Geomancies, REDCAT, Los Angeles, January 14–March 12, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Military technologies of surveillance also figure heavily in the filmic style of Ordinal (SW/NE). Between aerial views of landscapes, we see a herd of pigs in low-resolution black and white. This aesthetic looks the same as the infrared-sensitive, thermal imaging technology used in drone surveillance, where whiteness marks what is alive and warm in a dark landscape. In this cinematic recreation of a biblical scene of demonic possession, the demon announces, “My name is Legion for we are many,” and leaps into the bodies of the pigs. A close-up of a squealing pig reveals the animals to be CGI. As the pigs stampede off the cliff, their death is a simulation. In the Bible and in Ordinal (SW/NE), demons occupy a human body before Jesus moves them into the bodies of pigs. The possessed man is human and worthy of saving by virtue of his unsuitability to enslavement: “For he had often been restrained with shackles and chains, but chains he wrenched apart and the shackles he broke in pieces and no one had the strength to subdue him.”19 Full humanity (bios) then is granted to those people who can reject enslavement, and who can distance themselves from the animality of mere life (zoe), refusing to be mere livestock or tools possessed by others. The death of the swine, that which is demonically marked by coordinates (SW/NE), makes possible the life of the human. The demon spirit its between these two physical forms—swine and human, zoe and bios—and creates between these poles the realm of “bare life”—an animalized, barely human existence that Mbembe argues finds its form in the figure of the racialized slave.

The history of possession can be traced to the plantation and the colony as sites in which bodies are instrumentalized to carry out the will of others. Historically, on the plantation, the enslaved refused to be subdued through uprisings and the literal breaking of shackles, but also through subtler means. In the New World, slaves commonly took on the habit of eating dust, and this “Cachexia Africana” was one of the leading causes of slave death in the American South, second only to yellow fever. Some speculated that perhaps slaves ate the dirt to supplement their constant malnutrition and meager diet, a deficiency of B vitamins, or an infestation of parasites. But, in 1835, the physician F. W. Cragin surmised that slaves “willfully” and“craftily” chose slow suicide through a “desired repast…of charcoal, chalk, dried mortar, mud, clay, [and]…other unnatural substance[s].”20

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

Indigenous and African slaves also used their knowledge of plant poisons and abortifacients to threaten abortion or suicide as a form of bargaining in the “crevices of power,” where the only power to be had in a powerless situation was the elimination of one’s own life and ability to give life.21 This acted coercively on the master not through a valuation of the slave in terms of his or her equality or humanity, but solely through the economic value of the slave’s body as property.22 Many notable slave uprisings, such as the Haitian Revolution, relied heavily on an interspecies confusion of bodily boundaries. Slaves infiltrated the water and food supply with biological poisons, introducing the sap of plants, the spores of fungi, and the venom of other animals into the bodies of their white masters, who sickened and died. Biological warfare causes a confusion of hierarchies. The term host undergoes a revision of meaning, revealing the breadth of its original Latin eponym hospes which contains the seemingly contradictory meanings of guest, host, and stranger within one word.23 The body of the white master, who previously thought of himself as a host—as in a subject providing largess and hospitality for his guests—becomes himself estranged by the new parasitical relationship to host and is no longer a subject but an object for the parasite: a house, tool, or food.

Consider the parasitic wasps of the genus Glyptapanteles, who inject their eggs into the soft flesh of living caterpillars. Inside the caterpillar’s body, the wasp eggs hatch into larvae and slowly feed on the caterpillar’s innards before eating through its skin to be born. Strangely, after the wasp larvae emerge, they turn around and patch the wounds they just made in the caterpillar’s body. The caterpillar survives and uses the energy and resources it would have used to spin the cocoon for its own transformation to weave instead a protective cocoon around the wasp larvae. It guards them against predators for the rest of its short life. Thus it replaces its commitment to propagate its own kind and takes on the wasp’s desire.24

Many popular science articles use the figure of the zombie to talk about these parasitic relationships between insects. The sensational figure of the zombie in American cinema emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, during the United States’ occupation of Haiti.25 Hollywood inverted the folklore of the zombie—originally an expression of the horrors of slavery—to be a mindless body controlled by others and used the figure to speak of white fears of miscegenation.26 When Ruperto and Keagy raise the specter of the fungal spores that cause valley fever, they are activating the parasite as a demonic relation. The parasite possesses the body of the host and changes its subjectivity, its place in the hierarchy. It works from the inside out, hollowing the body and making it a slave to a foreign will, a non-being, a zombie, a void.

For Geomancies, the southern corner of the REDCAT gallery is painted black. When Kazimir Malevich showed Black Square at The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 in Petrograd, in December 1915, he positioned the painting high on the wall in the corner of the room, taking the same spot that the icon of a saint would normally occupy in a traditional Russian home. The first Black Square (there were four versions between 1915 and 1930) was painted in 1915, though Malevich dated it 1913, the year he used it as a design for a stage curtain in the futurist opera Victory over the Sun. The black-painted corner of the REDCAT gallery can be read as a multivalent sign. On the one hand, it is an extension of Malevich’s Black Square— a supposedly non-referential thing in itself that replaces the icon and does not point to any future event or object in the world. On the other hand, it could be read as the opposite—an empty stage or backdrop waiting for the bi-monthly performance Possession (2017), in which Ruperto has choreographed a work for two dancers, who re-enact a mirrored version of the formal movements of possession, based on the infamous scene from Andrzej Zulawski’s 1981 film Possession, which features the actress Isabel Adjani.

The performers of Possession have a curiously evacuated affect. They take Adjani’s bodily movements and facial gestures from a cinematic scene that is charged with emotion and replicate them with the feeling drained out. What we are left with is a twice-removed representation of flesh animated by a demonic force—a robotic, opaque husk of movements and twitches. The deadpan style of the actors in Ordinal (SW/NE) also embodies this evacuation of emotion, and this hollowed-out body is articulated in the glaringly white scene at the doctor’s office, where the film’s main character Josiah, a young African-American man with an asthmatic cough, is told by the female Asian doctor, “You have nothing inside of you.”

Miljohn Ruperto, Possession, 2017. Performance at REDCAT, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

In summarizing different Aristotelian views of “the void,” Eugene Thacker writes, “Ambiguity ensues, as philosophers attempt to render the nothing as something; the void is not the container itself, but the nothing that ‘is’ in the container, at best negatively demonstrated by displaced space (e.g. water poured into an empty vessel). In this plenist view, the void is simply that which is not-yet-full, or that which is not-X, where X denotes an existent, actual body and the void simply marks the interval or relation between one body and another, the space in-between.”27 In considering the Aristotelian void as the space of relation between X and not-X, I think about Frantz Fanon’s psychological construction of race. Fanon writes, “Not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man.”28Conceptualizing the void and its horrific otherness, like the construction of race, is a fluid space constantly in the making, a poetics of relation. The moral values or affective qualities of the other, not-X, become inextricably bound to one’s own meaning and being, even as that meaning is made through alienation. But the objective is no longer to determine the nature of X and not-X but to question the very ether they supposedly float around in. “No longer are my intimate impressions ‘personal’ in the sense that they are ‘merely mine’ or ‘subjective only’: they are footprints of hyperobjects, distorted as they always must be by the entity in which they make their mark—that is, me. I become (and so do you) a litmus test of the time of hyperobjects. I am scooped out from the inside.”29

Ordinal (SW/NE) is primarily narrated by a young Filipino woman whom we hear but do not see in the film.30 She plays the character of X, who has recently given birth and, as we learn at the end of the film, has contracted valley fever. We understand her illness as the result of a dark bargain with Pazuzu because the narration announces “evil for evil” and goes on to describe how protective mothers invoke the evil of Pazuzu to ward off the evil of Lamashtu, a Mesopotamian goddess whose furies are oriented towards the destruction of human children, while nurturing non-human animals. The sacrificial mother is a well-known trope, as is the use of the cis-female body and its reproductive potential to metaphorically reference the fertile, agrarian, and productive potential of land.31 Anthropologist Anna Tsing writes of how the state’s promotion of cereal agriculture supported a patriarchal realignment of power: “The pater familias was the state’s representative at the level of the working household…who ensured that taxes and tithes would be drawn off the harvest for the subsistence of the elites. It is within this political configuration that both women and grain were confined and managed to maximize fertility… This obsession with reproduction in turn limited women’s mobility and opportunities outside of childcare… [I]t seems fair to call this [rise of cereal agriculture], …echoing Frederick Engels, ‘the world historical defeat of the female sex.’”32

At the end of Ordinal (SW/NE), after giving birth to a human child, the character of X becomes pregnant with spores. Like the fetus, the spores of coccidioidomycosis, incubated in the warm bronchioles of her lungs, feed parasitically off of the mother’s nutrients. The birth of one is celebrated and protected—a future productive citizen—whereas the other, as it grows into a multitude, temporarily or permanently takes away the productive potential of the mother or the prisoner working in the field. The parasite, like Lamashtu and her breast-fed puppies, troubles the idea of proper maternal relations, as it also disrupts the hierarchies and clear boundaries of host and guest, master and slave, X and not-X.

The disembodied character X is complemented by the main character that we do see: Josiah. We first see him sitting on his bed with his inhaler, reading off the vital signs of his body and of the environment. As Josiah is overcome with a fit of coughing, a poster of Malevich’s Black Cross (1915) that hangs above his bed swings loose from one corner, forming an X and deepening the connection between him and the disembodied character named X. In many religious traditions, the cross signifies life and death: the crossroads. Transformed by a possessed wind that blows through the bedroom—a wind potentially laden with dusty spores—the cross becomes an X.

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

After the end of slavery in the New World, X took on specific meanings. X became the naming device for that which cannot be named, the symbol that stands in for the signature of an illiterate slave, the signifier of a lost name, homeland, lineage, and family. Without being a name in itself, X is a device, a sign that points to irrecoverable and unknowable loss. Because of literary discourse and actual history that associates blackness with dispossession (of homeland and self-possession of one’s own body), “black geographies are often unimaginable because we assume they do not really have any valuable material referents, that they are words rather than places, or that their materiality is always already fraught with discourses of dispossession.”33 X stands for irrevocable loss but also X marks the spot: the hypervisible, marked, racialized body. This is also the body on display, the body that performs and for whom the performance never ends. In Ordinal (SW/NE), Josiah’s encounters with the demonic are punctuated by other moments in which he is dressed as a mascot, dancing in an empty gym. Because the mascot has no cartoon head, just Josiah’s head emerging from the overly padded and enlarged costume, we understand that the mascot is Josiah himself, endlessly performing, with or without a visible audience; we are always watching him. X can never exit the stage.

Toward the end of Ordinal (SW/NE), Josiah and a circle of friends take turns freestyling dance moves for each other. The dancing body becomes robotic and zombie or puppet-like, angular in its movements. During Josiah’s dance, his hand takes his shirt and moves him around as if it is the hand of another person. Each spasm ripples like a fit of coughing through the body, like the rupture of an inner demonic state working its way to the surface. Superimposed on this dance scene, Josiah’s voice speculates,

I once heard that the word influenza had two possible etymologies. The first is the more accepted one where in an alchemical cosmology the stars influence our bodies through an invisible cosmic fluid… The second theory is about uncontrollable mimetic contagion… The disease influences my body to copy the cough and mime the symptoms of the sickness that I see… I sometimes wonder about the difference between choreography and freestyle. If choreography is influence imposed upon you by outside bodies (like stars, or other humans), what is freestyle? It radiates from the inside out. Is my evil star inside?

Timothy Morton writes that the word disaster comes from dis-astron, a dangerous or evil star that takes place against a relatively stable outside horizon, in order for its deviance to be seen. In the Ptolemaic-Aristotelian world view, the earth was stationary and central, surrounded by a machinery of the spheres, a series of concentric circles made of a glass-like, transparent material—“quintessence”—which literally held the stars and other planets in place so that they appeared to move while the earth remained still. This was the common system of belief in the Middle Ages among Christian, Muslim, and Jewish religions alike.

Geomancies, installation view, REDCAT, Los Angeles, January 14–March 12, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

So what, then, does it mean if disaster is repositioned as internal, imploding? If choreography is the organization of a body imposed from outside that body, like the master’s orders to the slave or the surveillance drone that controls one’s actions and mobility from above, freestyle is assumed to be a space of internal freedom. Arthur Jafa’s description of jazz could apply here. Jafa writes, “Jazz improvisation is first and foremost signified self-determination. This actually precedes its function as musical gesture. For the black artist to stand before an audience, often white, and to publicly demonstrate her decision-making capacity, her agency, rather than the replication of another’s agency, i.e. the composers, was a profoundly radical and dissonant gesture.”34

Freestyle and jazz improvisation in this context speak of self-possession, imagining black geography within a language of dispossession from one’s agency, one’s homeland, one’s own body. This imagined geography is not based in colonial narratives of conquest and possession but rather is a “landscape of relation,” of ever-moving, ever-shifting “demonic grounds.”35 Drawing from mathematics, physics, and computer science, “the demonic connotes a working system that cannot have a determined, or knowable outcome. The demonic, then, is a non-deterministic schema.”36 We find it so difficult to think of X and not-X, evil and good, parasite and host, outside of a relation of enmity, colonization, or assimilation to the other’s desires. But in Ordinal (SW/NE), X is a shifting thing: it is a woman’s voice cracking with illness, it is a black square spinning into a circle, it is the tetra winged shape of Pazuzu the demon in flight.

Rini Yun Keagy and Miljohn Ruperto, Ordinal (SW/NE), 2017. Video still. Digital video, 43:44 min. Courtesy of the artist and REDCAT.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at Gasworks, London; Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles; Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles; 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica; and CAAA, Guimarães, Portugal.