If it is dangerous to make man see too much how he is like the beasts without showing him enough of his grandeur, just as it is to make him see his grandeur without showing him enough of his beast-like qualities, so it is even more dangerous to let him ignore one or the other.

-Blaise Pascal1

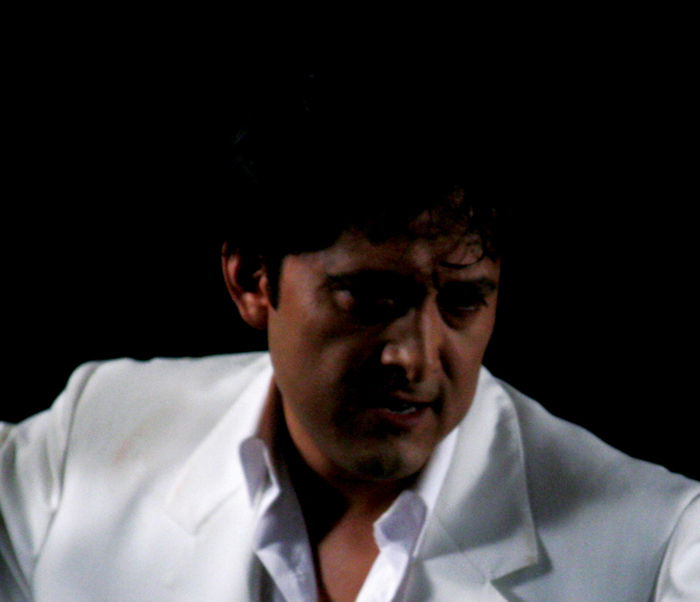

With sparkling elan, tap dancing feet break the silence of a blackened space. Within a few beats, a male figure stands revealed in all his culture’s refinements–graceful in dance, sophisticated in his well-cut, white suit–as he performs the Malamba Sureno. Mere frames later, our gaze follows arcing chunks of meat leashed to his wrists, carnal boleadores accompanying the steps of the Argentine cowboy dance.2next, a dog barks, a pack is revealed, and the fight is on. This is Miguel Angel Rios’s compact new video piece, Crudo (2008), presented by guest curator Gilbert Vicario at LAXART. It is an immensely satisfying work.

Bloody meat in movement can incite, thrill, and tame–all at once. Here, it embodies what is perhaps at the core of what it means to be human and just might be the very trick of civilization itself: to emerge from beasts through artifice. There is no sense in Rios’s work of alienation from our cruder selves, unlike the kind of fashionable moral cleanliness we find expressed in a passage on bear baiting in Erica Fudge’s Perceiving Animals:

There was a Bear Garden in early modern London. In it the spectators watched a pack of mastiffs attack an ape on horseback and assault bears whose teeth and claws had been removed. People enjoyed the entertainment. We know this from the numerous reports of baiting which have survived. What we don’t understand is the nature of their enjoyment.3

If we consider how the brave and noble dancer in Rios’s work steps in place of the bear for our delight, what is the nature of our enjoyment in Crudo? The most incredible element of the dance is how clean the white suit of the dancer remains throughout the piece. By his surefootedness and masterful handling of the boleadores, he succeeds in keeping the meat, and thus the dogs, away from his pristine self. It is the struggle to define the grandeur and bestiality of the human via the raw contact of bodies–of animal with culture, of spectator with spectacle–that distinguishes this addition to the lineage of artworks that feature live animals.4But our joy and understanding of the piece derive not only from following the dancer’s refined legwork, the snarling dogs and the whirling balls of meat. It is in the use of meat, a crude signifier of raw needs, and how it joins the dancer and the dogs in an encounter that is unnatural and unusual.

What makes the choice of animal particularly vivid is our Westernized cultural perception of the domesticated dog. As a pet, the dog loses the right to be fully animal. But within a pack, a dog regains its wildness and loses its individuality, as humanly experienced. Indeed, Deleuze and Guattari would have us consider the human individual as an isolated phenomenon of natural history, since “every animal is fundamentally a band, a pack.”5In Rios’s video, the lone dancer never loses his composure. The dogs might attack and attach themselves to his suit, but at no time do they appear to threaten his cool. They are, thus, domestic dogs, existing precariously in the no-man’s land between human and non-human worlds. From his dance with dogs and meat, the man emerges as pristinely superhuman. Crudo shows us Animal in the house of Culture, and Culture in the house of Animal.

Shaped to a range of sizes from large chunks to mere morsels, the meat is never shown being eaten or held in the animals’ mouths. All we see are the grabbing attempts by a gang of dogs, individually making their forays into the orbit of the dancing man. This is the starkest reminder that the meat is a transactional device, a means to pit the animal against the man. The dogs’ desire is clear: to consume gobs of flesh. It is the dancer’s intent that requires closer study. His only protection is his stainless suit. And underneath this fine outer skin is his own meat. Surely he does not do this to exercise the dogs, but rather to teach us all a lesson about passions and mastery. Its discursive arcs and feints demonstrate a way to master those bodies of meat, the dogs, and our flesh-clad selves. There is nothing truly frightening in the interaction, since the dancer appears in complete control. There are only hints of mortal danger, of the dogs threatening to overwhelm, to eat raw flesh.

What does make the interaction feel threatening is being forcefully and somatically put in front of the living flesh and the death of flesh. Similar to that progenitor of inverted still lives, Pieter Aertsen’s seminal Meat Stall (1551), the subject of Crudo is of impolite and questionable appropriateness. It proposes neither a joke nor a meditation on mortality. It is neither someone’s bottom being pinched nor a war scene suppurating with flesh. Unlike in Meat Stall, where the flesh has been made ready and displayed for ultimate consumption at our tables, in Crudo the flesh is formed into balls and bound into a tool typically used for hunting and here used for dancing (and for securing an elevated place in the natural order). It is neither the flesh of a recognizable body nor of an everyman; it is not of a hero, a partisan, nor a patriarch. unlike its still-life precedents, Rios’s scene caters neither to the narcissistic elite nor the mercantile class with a vague memory of religious subjects. Crudo features workaday meat as a workaday reminder; it is neither heroic, epic, martial, nor religious. It reminds us of our physical frailty, that we too become crude meat, and that it is through our cultural artifacts that we order ourselves and the world for our preservation.

The camera angles of Crudo set one up to wonder: Am I dog, meat, or dancer? Who is in control? Figure and ground shift with each swift change of camera angle, establishing equivalence between the three points of view. Rios is animalizing humans and reminds us vividly, proactively, and with all the gravitas of a still life that, in the words of Francis Bacon, “we are meat, we are potential carcasses.”6 All are potential flesh, even those of us watching on the sides.

In presenting visual metaphors, 16th and 17th century northern European artists sought to examine via a spiritual lens the vanity of human attachment to worldly pleasures and the brevity of life. In foregrounding meat, that which sustains us and of which we are, we can trace a direct line from Aertsen’s Meat Stall to Carolee Schneemann’s performance Meat Joy (1964). Yet, this tradition depends on meat’s ability to evoke nourishment and death, and on art’s ability to preserve or facilitate the rotting.8 What is unique about Rios’s use of meat is how it is neither preserved nor rotting, it neither decays nor causes decay. We do not even see the meat being eaten by the dogs. Instead, it is blurred in motion and disappears in the visual dance. It is as if to say that, magically, nothing truly uncivilized can happen within the frames of this work, for it would surely be choreographed away. Nothing compromising would ever make the cut of this virtuoso artwork.

Neha Choksi lives and works in Mumbai and Los Angeles.