At the Miami art fairs in December, a gallery owner at New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA) told me that there was a certain place on one wall of his booth that he and his assistant dubbed “the money spot,” because easel paintings inexplicably sold more quickly when hung there.

Anyone paying attention to contemporary art and its market knows the significant effect of art fairs. In my research, I discovered that, regardless of a gallery’s market niche (established artists, emerging artists, secondary sales, etc.), roughly one-third of participating galleries’ yearly net revenue comes from fair sales, and that’s not including residual sales after each event. Art fairs impact artists’ practices as well. Dealers ask for artworks to ship to fairs constantly and artists must adjust their studio practice to meet that pressure. In addition, two big industry announcements — the artist list for the 2006 Whitney Biennial, and the shortlist for the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss prize—were announced during Art Basel Miami Beach.

While art fairs do a lot to validate the contemporary art market, they also do a lot to de-value most of their attendees. Navigating the tiers of art fair exhibitions in Miami during the first weekend in December 2005 was overwhelming, though socially intoxicating. Centered on the main fair — Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) — this aggregate event is invigorating, but its scale defeats one’s ability to evaluate the artwork it contains. ABMB organizers filled the city’s 500,000 square foot convention center with booths occupied by 190 art dealers. Walking down the wide boulevards that channel 35,000 attendees between gallery-cubicles, I found myself swinging my head from side to side to catch glimpses in motion of each gallery’s showcase. Every time my eyes rested on an object, I was distracted by something else or urged to keep walking and looking.

As a critic, I go to as many fairs and venues as I can, but always feel there is probably some key exhibition I didn’t know about; I look at an ungodly amount of artwork, but I always feel I missed the best pieces; I attend parties, but always feel there was one I was not invited to; I stay in a hotel I can afford, yet always feel a more expensive one would lead to better art and social experiences. Even the collectors who can easily afford airfare, the best hotels, and the artwork price-tags face the same hierarchical game: receiving the “wrong” invitations or no invitations at all, staying at the wrong hotel, missing the insider tips on the good deals. All attendees attempt to distinguish the value of artwork in a spectacle that constantly diverts one’s critical focus.

The art fairs hosted in Miami include ABMB, NADA, scope and — new for 2005 — Aqua, Pulse and Pool. They are all high-end tradeshows designed to sell artwork and accelerate the business of exhibiting, dealing, and collecting art objects. Integral to that market activity is evaluation of the artworks on display (what is worth looking at, what is worthy of being collected, which artists are worthy of our limited attention, etc). This evaluation function at art fairs contrasts with biennial exhibitions, where curators and other professionals in the field evaluate artists and artworks. Biennial audiences view what has already been evaluated. A 200-member committee for ABMB selects galleries and some specific artists for projects, but ultimately it is dealers and consumers who perform the evaluation at the Miami art fairs.

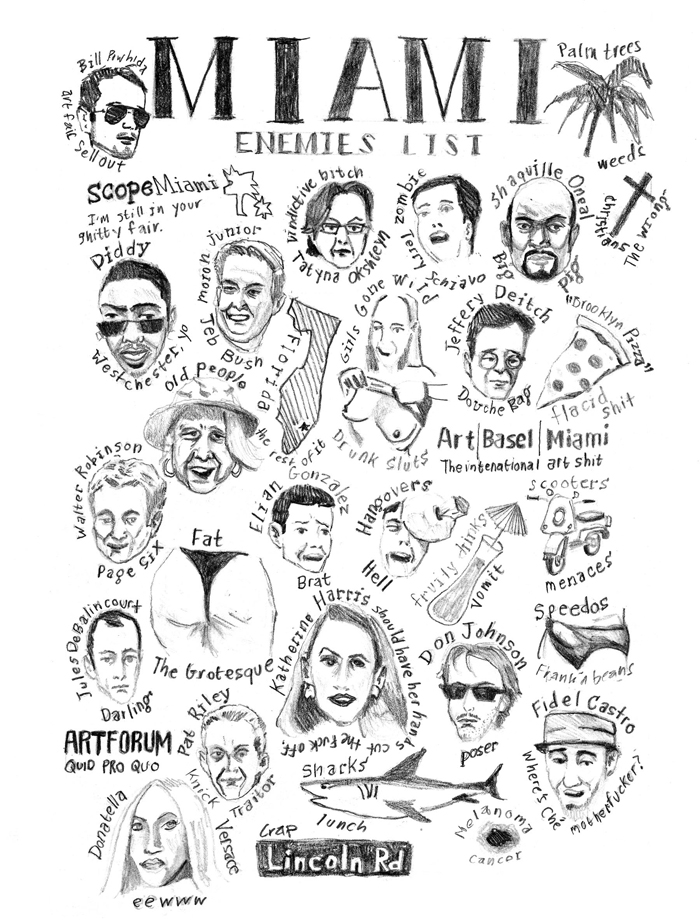

William Powhida, Miami Enemies List, 2005. Shown and sold to private collection at Aqua. Photo courtesy of the artist and Platform Gallery. 11” x 14”, graphite on paper.

Evaluating anything requires that one apprehend the whole to which it belongs in order to measure it against the other constituents in the field. However, these fairs coalesce to form a citywide event that is impossible to master for two reasons. First, there is simply too much to see, and often the most viewers can muster is to measure artworks that catch the eye against other standouts or to use a whole fair as a typified stand-in for the individual objects it contextualizes. Secondly, ABMB is a theatrical manifestation of the art market. While it has always been true that the value of artwork is based on social agreement, and that this condition means the standards by which an artwork is measured can seem elusive, art fairs introduce a new complication into this fluid system. ABMB is such a powerful social ritual that it becomes an illusion of objectivity, legitimizing all the artwork (and galleries, and people) it touches. The minor fairs surrounding ABMB also benefit, gaining more clout than they would on their own, and passing this social power down to the objects they contain. Through its overwhelming congestion and high social stakes, ABMB takes the power of evaluation away from the viewer and puts it in the hands of the market and its consensus system. An individual is perhaps more encouraged to purchase art in this environment, but he is less able to judge it. Objects that stand out or are more spectacular in this context are more desirable and more valuable. As a result, the art market itself is the most celebrated and valuable form here, trumping the artworks.

Before the art fair boom, value was bestowed on artwork through conventions such as the white cube — the pristine gallery atmosphere that both created value for objects and separated them from the market — and by the art critic. Besides increasing the value of artworks by discussing them, critics distanced art from the crass reality of the market by sealing off its function as a conceptual symbol from its function as a financial symbol. For the critic, an artwork’s function is based in its display — artworks are written about when they are shown. The production of a piece is often only considered when it contributes to the form of the work, and a work’s function as property or currency is rarely addressed in writing — just as it is rarely addressed in its display.

Currently, criticism concerning art fairs is comparatively weak and inconsequential, usually falling into one of two categories: beat journalism or lamentations over the mega-mall atmosphere of art fairs. The same topical coverage of art fairs appears in newspapers and art journals alike, the latter lacking the in-depth analysis for which one would hope. Part of the problem is that criticism’s distancing function was best served by addressing artworks as galleries did — individually, in their own universes, autonomous unto themselves.

In the age of the art fair, criticism should be venue-driven or institution-driven, rather than object-driven; it should reflect the overwhelming, overarching social relativism in which the artwork is displayed. Not in an effort to create value for institutions (physical and ideological), but so that we can unearth the possibilities we create and obstruct through that value. Otherwise, the art critic as we know him may drift toward obsolescence, like the white cube. (Most gallery owners I speak with report attendance down in their galleries and up in their booths.) Or the art critic may become the art guide, helping spectators navigate impossibly overstuffed art fair environments, writing indispensable primers before the big weekends in Basel, New York, Cologne, Paris, Madrid, and Miami.

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (current art world favorite or foil, depending on the camp) provides a theoretical lens through which we can begin to examine some critical questions about the art fair phenomenon. What kind of value do art fairs create? What kind of artwork does an art fair produce? Using Bourdieu’s concept of the Field of Cultural Production from his essay of the same title and concepts from his book Distinction, I want to examine the 2005 Art Basel Miami Beach and concurrent fairs as a unique circumstance responsible for artworks and other cultural products specifically made for and evaluated in that environment. Besides these texts, my method includes visiting the site, interviews, fair catalogs and promotional literature, and the exhibitions and artworks themselves.

Aqua Fair, Aqua Hotel in Miami. Photo courtesy of Alice Wheeler.

In applying a Bourdieuian framework to the Miami art fairs, we must first define the theorist’s terms. Any abstract-able, autonomous form of competence can be a “field,” according to Bourdieu. This means that there can be a field of contemporary art, of art fairs, and of Miami as an art community. Miami during the art fair week is also a field. These are all areas — geographical, economic, and social — where constituents engage in activities that advance, suppress, value, and dismiss elements within the field. The art fair is a social construction, a “field of forces and struggles” in Bourdieu’s terms, because on the one hand we engage in the intricacies of the event without thinking about them, and on the other hand we struggle to identify the complex dynamics of, and get close to, the centers of power and meaning, whether they are people, booths, events, or objects. It feels as though we are constantly searching for something while at the fair, even though the artworks, the alleged purpose of the event, are right in front of us.

In Bourdieu’s field of cultural production, autonomous constituents like music, literature and art can be abstracted, identified, and examined as unique disciplines—each is a field in its own right. Subcategories exist whose categorization is based solely on the other possible positions within the field (contemporary art, Renaissance art, High Renaissance art, etc). These positions are dynamic ones, dependent on the other positions within the field for their legitimization and definition, which is always changing relative to the other positions. Each Bourdieuian field maintains a unique set of forces and struggles between positions in a hierarchy.

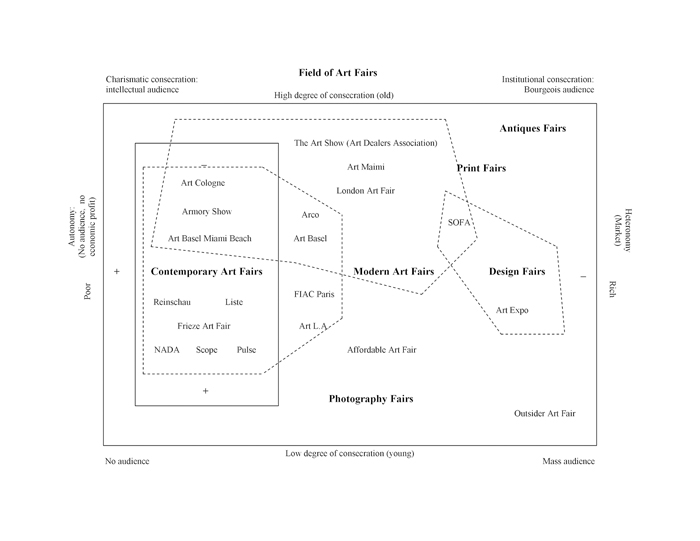

In examining the field of art fairs as a whole, Bourdieu’s principle of “hierarchization” demystifies the popularity of Art Basel Miami Beach as a position, compared to the other fairs (positions), and other “possibles” in the field. To understand the relationships between positions in the field of art fair possibles and between positions in the field of Miami possibles, I found it helpful to make a diagram similar to the one Bourdieu constructs for the French literary field in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Bourdieu’s construction consists of a rectangle delineating the field as a whole and a smaller interior rectangle delineating the position of power, with positive and negative poles indicating dominant and dominated elements, respectively. There are also poles related to power in society [the heteronymous market and autonomous high art, consecrated (old) art and unconsecrated (young) art, rich and poor] with corresponding audiences for the cultural products plotted between extremes. Bourdieu’s principle of reverse hierarchization explains that while works of drama might find a richer audience, it is works like poetry that dominate the field because they have more social power (cultural capital). The smaller rectangle contains those cultural products that have a more educated (initiated) audience and advance the entire field.

Figure 1, Field of Art Fairs, 2005.

In order to apprehend the slippery field that is art fair Miami, I have mapped the current field of art fairs as I understand it onto Bourdieu’s diagram (Figure 1). Types of fairs appear in larger, boldface type along with examples of types. Design fairs like Art Expo and SOFA have the least cultural thrust and are as validated (“consecrated”) as modern art fairs. Antiques and print fairs have been around the longest and their objects have been thoroughly consecrated by the field. International contemporary art fairs appear in the power position, in descending, negative (dominated) to positive (dominant) order. The criteria I considered for which dominate and which are dominated includes number of applicants to number accepted, attendance, coverage in art magazines, and the amount and quality of spin-off activities and events. In other words, I considered intra-industry forms of validation. I have only included a few examples of types for simplicity, but more could be added for greater specificity.

In keeping with Bourdieu’s model, the dominant area of fairs includes the newer, more speculative ones and the dominated include older fairs with more conservative artwork like the Art Dealers Association event. As the space of possibles is populated with exciting and glamorous new art fairs with edgy programming and young galleries showing young art (in other words, fairs with greater social capital), these new positions push the field of art fairs into new directions by defining with their existence what art fairs are and what they can be.

Since the positions are always dynamic, we can reconstruct a past year and find a different field. Switzerland-based Art Basel initiated the Miami Beach version of their fair in 2003, and this new fair in the field affected the positions of the other international fairs. For instance, Art Cologne had been in the socially dominant position in terms of young (less consecrated), less expensive, more experimental contemporary art. Miami Beach was Art Basel’s answer to the burgeoning contemporary art market and its inception pushed Art Cologne into a relatively dominated position, as the newer fair was more appealing to collectors of new artwork.

Organizers and publicists invent and exploit Art Basel Miami Beach’s geographic position, highlighting Miami itself as a hot city — in terms of temperature and titillation — one that has the exoticism of Latin America with all the creature comforts of the United States. As a “position-taking,” Art Basel Miami Beach shifted the position of Miami in the field of contemporary art. In addition, Miami’s own field of cultural production is different than it was before ABMB took position in 2003.

ABMB is organized into four subcategories, re-enforcing each with specific social capital. Art Galleries is the largest section made of booths occupying the center majority of the convention center. Art Kabinett, a new section for 2005, consists of smaller booths specially curated and inter- spersed among the Galleries and Art Nova booths. Twenty Art Nova booths line the outer edge of the exhibition hall as a section reserved for young galleries featuring artworks that are less than two years old. Art Positions is a section set a few blocks away from the convention center. It consists of 20 galleries, each in a 10-by-30 foot shipping container cum art fair booth. In a way, organizers construct this main art fair as they see the larger art market operating: Blue chip galleries selling mature artists at the center; progressively younger galleries with more experimental, newer art on the fringes; and Art Positions placed figuratively and literally “on the edge.”

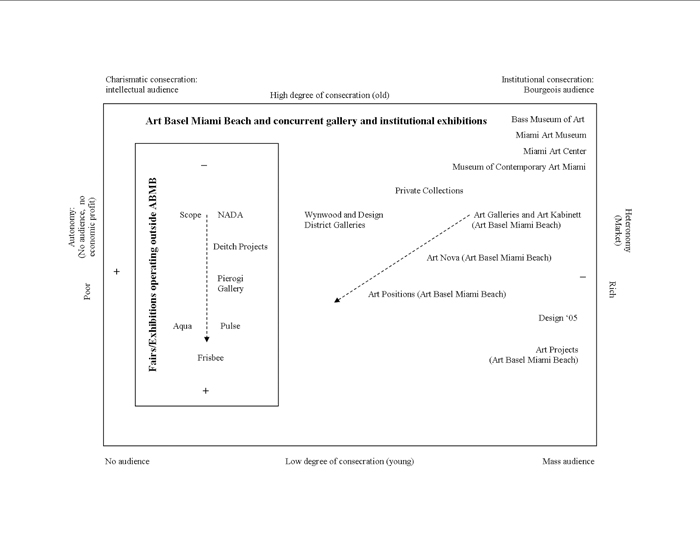

Figure 2, Field of Art Fair Miami, 2005.

I mapped my vision of Miami as a field of cultural production during the art fairs of December 2005 in Figure 2. I observed that the art fairs attempted to position themselves via public relations language, marketing, location, and selection process. Each conscientiously characterized itself through catalogs, guides and pamphlets. Guides, for example, position the guide-maker more than they orient the viewer. Pulse, a satellite fair orbiting ABMB, explains its purpose on the first page of their pamphlet: “PULSE, an invitational contemporary art fair, has been created to bridge the gap between established and alternative art fairs.”While the first half of the booklet includes a map of the booths and exhibitor contact information, the latter half includes an “Around the Town” section listing other fairs, museums, collections, galleries, and alternative spaces in Miami and Miami Beach. Pulse announces itself as an equal partner to the big fair and other fringe fairs, and proclaims art fairs as being on par with museums, collections and galleries.

Aqua, another new satellite fair for 2005, sites a lack of representation of Northwest and West Coast galleries in Art Basel Miami Beach and NADA, and brought a number of these regional galleries together to make exhibitions in almost every room of the Aqua Hotel on Collins Avenue. This fair employed an older style of hotel room display, a resourceful precedent set at the Armory Show art fair in New York’s Gramercy Hotel in 1994. At Aqua, galleries set up shop in one or two hotel rooms surrounding a palm-treed courtyard with a fountain and refreshments. Organizers explained they liked the Aqua Hotel for this courtyard structure and because the rooms featured white walls, overheard lighting, and cool cement floors — much like a contemporary gallery setting.

Scope, another ancillary fair situated on five floors of the Townhouse Hotel in Miami, positioned itself art historically with the Gramercy Hotel pioneers and geographically between the Miami Convention Center and the beach display of Art Positions. Scope has a strict policy that each participating gallery curate 85% of its room as a solo show. This is a move to retain the integrity of a white cube gallery, but most dealers reluctantly complied with this policy. Dealers don’t make as much money with solo displays and most seemed annoyed that scope organizers were trying to hold an ideological line that was never part of the art fair business in the first place.

The most interesting position-takings performed in Miami in 2005 belonged to Deitch Projects and Pierogi gallery, both of which occupied warehouse-sized spaces in the Wynwood art district. Geographically near Miami’s art galleries yet bigger than any of them, these dealers bypassed Art Basel Miami Beach’s cubicle architecture, overwhelm- ing environment, and evaluation system. Here, artworks appeared more like they would in a big group show. Pierogi gallerists said they turned down a booth at the main fair in order to show their artists in a bigger space that they could maintain control over and that their sales had not suffered in the least with this decision. In addition to the two-story warehouse blowout Deitch created, he also had one of the larger booths at ABMB in the art galleries section. I noticed other dealers doubling up at the fairs that would allow it. Byron Cohen Gallery, for instance, exercised two position- takings, one at scope and one at Pulse.

It is important to note the fair’s trickle down effect on permanent galleries in Wynwood and the greater Miami area. Since the audience (consumers) for art has increased in Miami, more dealers opt to open galleries there; but because the art at the fair is so specific, the kind of galleries opening occupy similar specificity — younger, emerging artists making stylized and experimental works. Emmanuel Perrotin, a contemporary art dealer based in Paris, opened a gallery in Miami recently that held its first exhibition and opening reception during the art fair weekend. Bas Fischer, also a Wynwood gallery, represents another aspect of Miami’s cultural production: artists and real estate. Its directors, Hernon Bas and Naomi Fischer, are both Miami artists who attended the New World High School, an art school in Miami. After college, both artists returned to Miami; real estate mogul Craig Robins gave them a studio and gallery space in the heart of the Wynwood district, where he owns many of the buildings. Robins is a contemporary art collector and powerful advocate, along with other collectors like the de la Cruz, Marguilies, and Rubell families, for Art Basel to establish a contemporary fair in Miami. The resulting increase in social capital for these patrons, in economic capital for their collections and in the Wynwood property holdings, defines their positions in the field.

In Figure 2, Miami institutions are the most consecrated and above regular market activity. Private collections, like Marguilies’s and Rubells’s are younger and have relatively more autonomy. The Wynwood and design district galleries, among which Bas Fischer and Emmanuel Perrotin have the most cultural capital as they feature the most cutting edge art, follow after that, closer to the socially dominant position than the institutions and collections. In Figure 1, Art Basel Miami Beach appears in the dominant rectangle, but in Figure 2 it is dominated by the fringe fairs that orbit the main event. This is because in terms of the Miami fair field specifically, there are many reasons to consider Art Basel Miami Beach a legitimate and legitimizing institution now, and as such it is consecrated out of the reverse dominant position. Anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon can be seen in the fact that most visitors came to ABMB on opening night; on other days the fair was noticeably less crowded. The action shifted to the alternative fairs, as collectors, curators, and other artists sought new artists and styles.

What kind of artwork does an art fair produce? The conditions of the art fair exclude certain types of artwork such as most video, sound, installation, and some types of sculpture because shipping and/or installing them is economically or physically prohibitive or they don’t show well in the environment. Contrarily, these conditions seem to support forms like drawing and easel paintings. At the Aqua fair, I saw a lot of works on paper, a lot of saturated color and attention to line, pattern and flatness. Perhaps this is a survey of current art trends in the region that Aqua represents or perhaps these works are merely the easiest to transport and have visual qualities that attract consumers in the art fair environment. It follows that artists who make work that shows well in the fair environment may rise in prominence over others who do not.

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, DOWNLOAD, 2005. Crushed sea-to-land container, 2 x 12 x 40 feet. Courtesy of the artists and Punto Gris, Puerto Rico.

Some booth-bound artworks were self-aware, sardonically addressing their own circumstance at the art fair. Although they may fit Bourdieu’s dominance criterion in that other producers will find them intriguing, they were primarily produced for sale at the fair. William Powhida’s Miami Enemies List (2005) and Dear Rich Art Collector (2005), for example, depend on a high level of art-market competence for meaning. Artworks that challenge the consumerism of the fair may have an important role for the artists and critics who see them. They are memorable in their subversion, also separating them from the mass. For example, artists Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla completely flattened the orange Art Positions shipping container allotted to their gallery Punto Gris, making a questionable consumer object out of the sales structure. On the flip-side, Container W, also one of the Art Positions spaces on the beach, held sleek white sofas and potted grasses with brochures and sales people pitching a new hotel and condominiums coming to South Beach.

As consumers of art we are constantly engaged in a process of distinction and the artwork we see in Miami’s fair environments become part and parcel of that sorting process that defines and validates personal taste. So, how do these events produce taste in artwork? Education is a key component of Bourdieu’s theory of taste development. He looks specifically at traditional tiers of schooling — including primary, secondary, and higher education—and their corresponding effect on taste in cultural goods. While this is certainly a factor in who is aware of and attends art fairs, there is also an education process (“competence”) specific to contemporary art collectors, and art fairs are increasingly integral to that competence. Magazines, accurately or not, often use art fairs as a gauge for the field, and I’ve met many curators who do too, for that matter. Websites developed to aid new art collectors often direct them toward art fairs as a method of contemporary art education. Since the business and architectural conditions of the art fair direct the art that is displayed, collectors, curators, and other artists’ educations are likewise directed. Perhaps the heralded “return to drawing” became critically important only after art fairs made it a market necessity.

The growth of a dynamic art center, as it appears Miami is becoming, is exciting; I do not mean to denigrate it here. This growth necessarily comes from financial investment in contemporary art. But Miami, ABMB, and art fairs in general are part of a new phenomenon that requires new criticism. Artworks and artists are not randomly successful here; pieces that are apprehended in a glance and the young artists who make them garner value in a market driven by speculation rather than validation of art. Their success is shaped by the art fair environment, where more art is seen and sold now than in traditional galleries, and for which much of our current artwork is expressly made. Bourdieu’s theories are merely one tool for the body of criticism that is needed to address this new social context of art production, circulation, and valuation. Objects and texts that interrogate this phenomenon are necessary in order to advance the entire field.

Meredith Goldsmith earned her MA in Visual Criticism from California College of the Arts in 2005. She is currently a visiting lecturer in art history at University of Texas, Tyler.