In the fourth and final contribution to a series of conversations between artists on medium and practice, Matt Keegan asks his peer and friend Fia Backström to discuss the structure and content of their work. Using William Greaves’ film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One as an anchor, this conversation investigates the role of power structures, collaboration, and collectivity in the work of the artists. One common thread that is shared here with the previous installments (including conversations between Kerry Tribe and Althea Thauberger with Melanie O’Brian; Dont Rhine and Janna Graham; and Sean Dockray and Hugo Hopping) is a focus on defining and re-defining the roles of artists as individuals, collaborators and collectives in relation to the audience who makes up the work as a reader, participant or in some cases, as content.

Shana Lutker

Matt Keegan: When I was a kid, I used to read this series of books called Choose Your Own Adventure, and when you got to the end of each chapter, you would choose the path you could take to continue the story. This kind of logic is at work in the structure of your interview with New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) that you turned into a web project (www.fiaBackström.com/nyfa) and in your three-part project Herd Instinct 360° (2005-2006). In each, information is presented to the audience to create moments of resonance and disjuncture. Both projects create a feeling that there’s so much more information available than what is presented; there are many side paths that the viewer can choose to take. With the NYFA project this is made explicit with the architecture of the site and the hyperlinks, and with Herd Instinct 3600, the tangents are embedded within one fluid monologue that you present in the beginning of each thematic afternoon..1 In the NYFA site, for example, when you are discussing the Black Panthers, images of the group appear, but so do images of Mac OS 10 panther software, and images of actual panthers. Language and image are both in and out of sync. One of my favorite moments on the site is when the user rolls over an image of the Gagosian gallery facade, and hears: “Gagosian, Gagosian, Gagosian…”

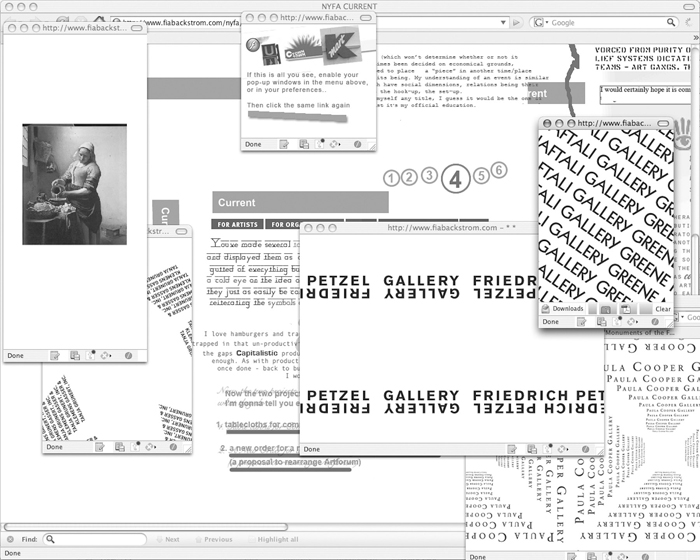

Fia Backström: Like the ocean … (laughs). Yes, the information age, it is very layered and less linear! The main difference is in the delivery and reception. Herd Instinct 3600 addresses the viewer frontally and in a totalitarian way. The viewer is placed on a seat in a group to receive that sermon. In the website, I can introduce hyperlinks to layer the information in another way. The internet gives the “feeling” of free choice—to click or not to click—even though most websites are actually very linear. In the NYFA project I wanted to challenge widely shared concepts of usability and navigation consistency. Take pop-up windows for example; users tend to turn them off because of the porn and the commercials that explode onto our screens. But I depend on them for this site. I made a first pop up which reads “F.U.C.K., you need to allow pop-ups.” And the “F.U.C.K.” uses different brands like C-town for C…It’s very corporate. This project is no doubt guilty of another web sin—“overnavigation.” You can click on almost anything and there’s no hierarchy of information. On a corporate website information for consumers is clearly laid out, and specific details about the company itself are usually hard to find.

Fia Backström, NYFA Current Interview/Project, 2007. Screenshot from website. Courtesy the artist. Fia Backström,

MK: It seems to make sense here to introduce the William Greaves’ film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) that we’ve been discussing. Both your work and his have these programmed parameters and are completely contingent on participatory activation. With the NYFA piece, it is up to the viewers to decide how far to delve in, or how much information they want to extract. The Greaves film’s success was contingent on the crew, cameramen, and sound people fully engaging with the rules that Greaves implemented…2; Even though the crew didn’t understand where it was all going, without their participation, there wouldn’t be this amazing resultant film.

FB: When I saw it I hadn’t read anything about it. I had no idea about the structural set up.

MK: Yeah, same for me.

FB: When the film started, I didn’t know what was going on, and it seemed like nobody did. It was this faux communal concept in Central Park in ’68, a great year. The black guy on the screen couldn’t be the leader—as a viewer and a citizen of this society, we’re programmed not to think so. This guy then tells the cameraman he doesn’t really know what’s going on; “Oh, I don’t know, I have no idea.” Similar interactions happen with the actors. When you realize that he is the director, the film becomes scary. How did he get in charge? This lack of authority was very uncomfortable for me.

MK: In Greaves’ film notes, reprinted with the Criterion DVD, he wrote that he wanted to relay as little as possible to the film crew and actors. And in the film, there are multiple points where he asks the crew and actors, “Well, did you look at the film concept?” But no one seems to understand the film concept, nor does he ever explain the film concept, so he refers to this thing that’s supposed to be the key, but no one really knows it and only half the people have read it. It’s important to note that at this point in his career, Greaves was already very established. He had been in feature films and many Broadway plays. He was a member of the Actor’s Studio. He was very accomplished. So, there’s the understanding that the crew is working with someone who’s very skilled and professional. This is opposite to his positioning himself as someone who doesn’t even know how to load a magazine for a camera.

FB: Yes, by not taking command over the movie, he places himself in a background position so the structural elements of the making of the movie come to the forefront. It could just as well have been a corporation or a nation. Here the crew can’t even inform themselves about the movie they are working on. It’s incredibly tragic and illuminating about human interaction.

MK: And because of that power structure it takes eight days before one of the crewmembers starts to critique the dialogue and say that it’s derivative. But in his critique of Greaves, the crewmember reveals his ideas of gender roles and identity.

FB: Ideology.

MK: And the ideology completely reveals itself. But then it’s interesting because of what you said before— about the rarity at that time of a black filmmaker in charge of a production that does not explicitly deal with race in the making of the film. Race is not touched upon, sexuality is touched upon, gender roles are touched upon, authorship, class—but race is never dealt with head on. And trying to understand the particular time that this film was made and how Greaves is showing the regular people in Central Park to set a social context while working towards the making of a “Hollywood” film, the complexities of it are really amazing.

FB: I found a site where the meaning of the title: Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One is discussed. “Symbiotaxiplasm” is a term that social scientist Arthur Bentley came up with for material created in the social realm for relations between individuals.

MK: And for groups as well, right?

FB: Yes. And Greaves added the term “psycho” to emphasize the psychological and creative part, to fit his situation. One person who wrote on that site was surprised that the term symbiotaxiplasm never had taken off. Someone else had replied it wasn’t surprising at all, as nobody can remember it. You cannot run a marketing campaign for a product with this name. That term for sure helps to stay out of the imprisonment of easy tag lines.

MK: Frustration with language is very relevant to visual art. With your NYFA project, I liked the way you set up a system in which the language and words have no footing or foundation, because when the second users click on them, they kind of pull the rug out from under themselves, and this lead to another thought, another idea.

Have you given up on trying to guide the discourse of how your work is received? Do you expect/anticipate default ways in which people will talk about your work? Or do you find from doing something like this web project—about a slippage of information—that it’s more interesting to perpetually try to complicate the conversation, rather then beating your head and wishing they get it right for once?

FB: In any artist’s work the concerns get clarified over time. Moves might be temporarily misinterpreted, or not visible in the current moment, but over the course of a lifetime the project of an artist becomes legible. For example, my appropriation of other peoples’ artwork could be seen as a way to deflect or play up a refusal of the making, while setting up relations and ways of using images to cut between artworks and other artifacts from image culture, as material moved into another discourses. This is a very different operation than the curator’s, whose primary concern ought to be to care for the work, not to use it.

MK: Yeah, absolutely.

FB: It’s important to be clear about our roles, because once we start collapsing definitions there is a loss of difference between actions; we lose potential for agency and personal responsibility is gone. In New York right now there is an enthusiasm for what people call “collaborations,” which many times look more like strategic positioning of two artists together, like a corporate merger to accrue higher value, layered with a romantic view of the inherent goodness of collaboration itself. The same goes for collectives. Why has it become so attractive to label something a collaboration or someone a curator? It seems many artistic gestures are censored into these options.

MK: Within “Still No Answers,” a short essay that accompanies the dvd of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, Amy Taubin writes, “The tumultuous New York film and theater worlds of the late 1960s oscillated between two opposing ideas: the auteur and the collective.” Taubin briefly states that the “auteur” could eclipse any mere actor, while “the New Left… idealized the collective, the commune and the group…” Also, Greaves “had a connection to all the worlds mentioned above, and a foot in several others as well…” It’s interesting to think of how collaboration functions at Orchard, an exhibition space in the Lower East Side in New York that we have both been involved with. Orchard frames itself within a rigorous practice and stages projects that have an agenda of social engagement. When thinking about late ‘60s film and theatre and its direct connectivity to the civil rights movement, it almost seems impossible to think that the contemporary art world could have a comparably direct relationship to an anti-war movement now.

FB: That would be unfeasible—and maybe this is cynicism—but does art have to join a political cause? Many collaborations might not be socially conscious and are more geared towards branding, but most of the time it’s a messy mixture. The collective is not necessarily liberal, nor is the individual or the singular unit reactionary or right-wing. The focus is always on the power structures—what one can say, who can say what in which role.

MK: And if you are working singularly, it doesn’t mean you’re not interested in collectivity. Not by any means do we have the understanding that those are the only two ways in which people work. Now, over thirty years later, you would think that there would be more slippery ways to approach inter-activity and collaboration, but those parameters seem to get more and more fenced in.

FB: Now, we’re all working in some kind of collective cluster, where exchange is a fluid osmosis in a membrane structure, whether we want to or not, and we’re engaging socially on so many levels. There is always interaction before and after the work. It depends on the kind of fantasy you want to play up or the label you want to publish from—the single vantage point of your own name or a more amorphous one.

MK: The Greaves film mines the psychology and interconnections of a group, and how groups are defined by social relations. It sets up a structure that I’m engaged with and your work seems to be engaged with and involves an investment in the audience and in a peer group, whatever that may be. Although I tend to function as more of a facilitator than you do.

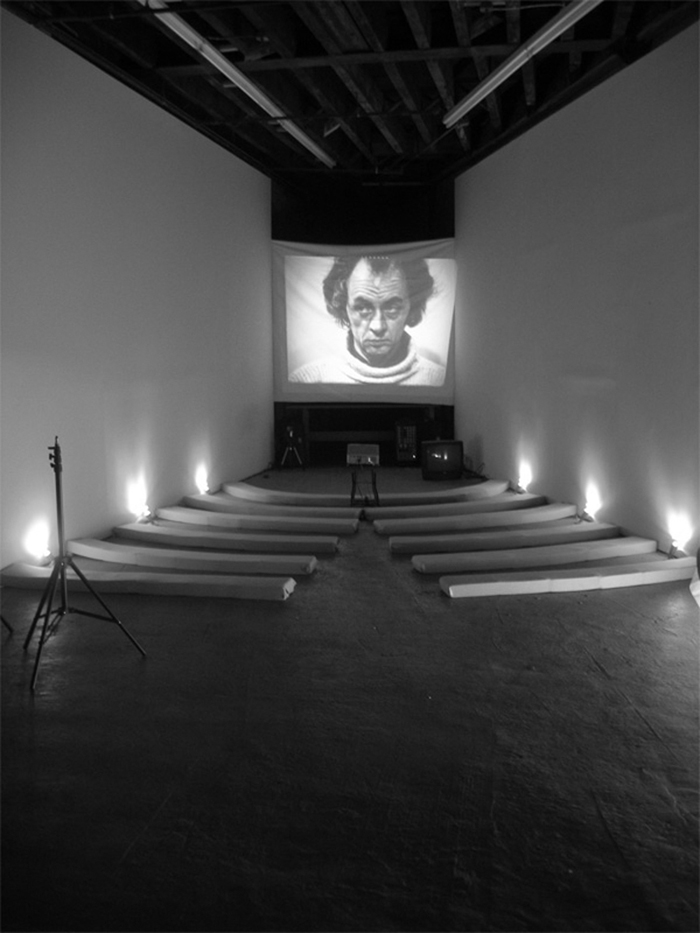

Fia Backström, Herd Instinct 360°, 2005-2006. Performance for event, refreshments, lectures, seats, lights, art at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. Photography: Matt Keegan. Courtesy the artist.

FB: In different ways, yes. I use a group as a signifying shifter depending on the parameters of the work. In Herd Instinct 360°, the act of gathering was the topic, where the audience was turned into the content, continuing this investigation of what an audience can be and do. Each time, different groups of people came, many of whom I had never met before. There was nothing closed or defined as “The Group.” The community fluctuated depending on what was going on; we gathered temporarily, new people joined, others fell off. Once you make clubs there is an exclusion, which is fine, but it needs to be acknowledged.

How do these things play out for you in North Drive Press (NDP)?

MK: The group that North Drive Press is continuously engaged with is made up of visual artists; NDP is made for and by artists. The thing that I like most about NDP is that it functions as a time capsule of sorts. Since there isn’t a predetermined theme, it is always exciting to go through all the interviews and multiples to see where there are natural places of overlap. This provides some insight into what was on people’s minds at the time of each particular issue. I love the moments where different contributors happen to talk about a similar topic and in some cases, completely counter an opinion put forth in another interview or text. This seems much more in keeping with the way a conversation transpires, and it is this exchangeability that is at the core of the project. Although my editorial hand is light, I am very aware of how this project grows and gains momentum over time. I hope that as NDP exists longer, it sets up more open-ended terms for contributors and what they can do with the project’s boxed parameters.

FB: And whereas you set up a firm structure for people to act within, Greaves deflects the responsibility to the extent that the crew and the actors make mutiny and meet in secrecy to question his capacity as a leader, while understanding it as Greaves wishes.

MK: Yeah, but it’s a productive mutiny.

FB: If a mutiny is the wish of the director, is it really a mutiny? It is obviously a problem if the leader wishes you to revolt. In response to relational aesthetics, I’ve set up totalitarian structures as, for example, in lesser new york (2005), which was an installation and a show of ephemera combined, which was up at the same time as Greater New York at PS1. In lesser new york both the system of display and the audience reception address this idea of totalitarianism. Visitors had to stand together and read the walls like a communistic wallpaper, as opposed to a lounge.

MK: And the fact that it was wheat-pasted, as well, added to that feeling.

Fia Backström, Eco Day, 2007. Happening; Materials: toilet paper, boxes, apples, garbage bags, ink-jet printed posters on boards, photocopies, musicians. Marabouparken, Stockholm, Sweden. Photography: Fredrik Holmqvist, Courtesy the artist.

FB: For the structure of the display or the interface I turned the material from the contributors into a seductive, repetitive Rorschach image. There was no mutiny from these participants… In Herd Instinct 3600 the audience was turned into the image and physical incarnation of the project, whether they wanted it or not. Eco Day (2007) was a happening at Marabouparken in Stockholm, where I went in the opposite directorial mode using open parameters more like Greaves. It was an afternoon event set in a sculpture park, where I gave the participants and the audience basic technology to develop. Some children were performing a dance with toilet paper, writing out different words, like “WASTE.” Other people were set to work on creating a fake pond, cutting up black garbage bags making them unusable, then placing them flat on the grass. The only refusals came from the musicians who I had asked to play a perpetual drone. They were not comfortable playing something that wasn’t going anywhere, and started to play songs. Eventually the children and the garbage bag people also felt a lack of purpose and a loss of sense, even though it had been hard work. I guess the problems are similar in the film, only in Eco Day the lack of purpose connects to contemporary life-style marketing rather than a fallen social utopia.

Fia Backström, Eco Day, 2007. Happening; Materials: toilet paper, boxes, apples, garbage bags, ink-jet printed posters on boards, photocopies, musicians, Marabouparken, Stockholm, Sweden. Photography: Fredrik Holmqvist, Courtesy the artist.

MK: It seems that you are trying to create an event that actually doesn’t fulfill any of the expectations of the audience and participants, and also doesn’t fulfill expectations of what a public piece called Eco Day should be. I was thinking about this in relation to scheduling events in commercial galleries, which is something that I have done, and also in relation to, as you mentioned, the unexpected audience or unusual suspects. Something that I’m very interested in, which I think that you do very well, is using the exhibition space itself to show how it can be reconfigured as a site—to function as a space for meetings, for exhibition, for a lecture; it has multiple possibilities in addition to its function as a space for commerce.

FB: Yes, one can twist the function of given structures, or set them out of sync. For example, at Greene Naftali, I showed Forged Community Posters (2006), where I superimposed ‘60s political slogans over images from artists represented by another gallery. When this fake community, which was formed on the posters, was moved into Greene Naftali gallery, it was transformed into something like a marketing campaign. The role of the commercial gallery was highlighted and displaced in this horizontal shift between the galleries.

MK: (laughs) I wish that people could see you mapping your ideas as we talk—I’m more of a rambler.

Fia Backström, Forged Community Posters (SDS slogans superimposed over images by seven artists represented by Andrew Kreps Gallery), 2006.

FB: When we were both asked to do an intrusion into Karin Schneider’s show at Orchard this past fall, I asked two men—the director of the Swiss Institute Gianni Jetzer and a younger artist named Alexandre Singh—to re-enact an interview between Simone de Beauvoir and Alice Schwartz. Gianni was Simone and Alex was the interviewer. You went in drag on Halloween as Karin Schneider, giving candy to the kids. Both of us looked at the idea of the author and our own artist persona. We placed ourselves into these scenarios in different ways; you went in as the artist herself, while I planted an older woman in the form of a man. We couldn’t find chairs, the two men had to sit on pedestals, it became a nice presentation.

MK: It’s interesting, because I wrote a review of Karin’s show for Modern Painters. And I thought very much about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One because her installation at Orchard turned out to be completely contingent on the participants. Although the structure itself was fixed, and the way some of the artists (like Amy Granat, Eileen Quinlan, and Melanie Gilligan) contributed was fixed in the space, everything else was up for grabs. The possibilities for entering into this work were endless. As long as the space was open, someone could be doing something in there. And as the installation changed, the reading of the show changed. When Karin asked me to do a performance, my immediate response was “I don’t do performances.” But I thought it would make sense to perform on the night when everyone was performing—Halloween. I did a very superficial rendition of Karin, which consisted of wearing a long, dark haired wig, and her signature baseball cap. I stood outside of Orchard as a representative of the space. The show spilled into the sneaker store next-door and there was a light that projected out onto Orchard Street. There are ways her show engaged the block surreptitiously, but in some ways the neighborhood was fully aware and willing in its participation. I thought it would be interesting to truly engage the block as a “neighbor.” I know from growing up in the suburbs that on Halloween you open your door. People you don’t know are welcome, and you give and get candy, and there’s this feeling of collectivity, as a neighborhood. In a prior project of Karin’s, she gave out psychotropic drugs to artist friends, and instructed them to make artwork that then was included as part of her solo exhibition. And although I was not giving out any LSD to the children, I thought that it made sense for them to become part of the performance, and they were recorded by both Karin and Amy Granat, who were shooting sixteen millimeter film of the Halloween event.

FB: When you use the word collaboration, what do you think it means? For me it is an exchange of ideas. One person might initiate the collaboration; eventually both would be involved in its development. It is not about equal labor. I see it as an organic exchange that grows, and though there is always a power structure present, there also needs to be some kind of equal consent to be a part of it.

MK: I think that when collaboration is good, it is very equal. And a collaboration is successful when one party contributes something that the other party can’t, and vice versa, and when there’s a rigor to it. The relationship gets synthesized over conversations, meetings, e-mails, phone calls, etc., resulting in something that feels like it’s been filtered through both parties. But the end result is much better than it ever would be with only one brain, voice, pair of hands…

FB: Or at least it would be something else…

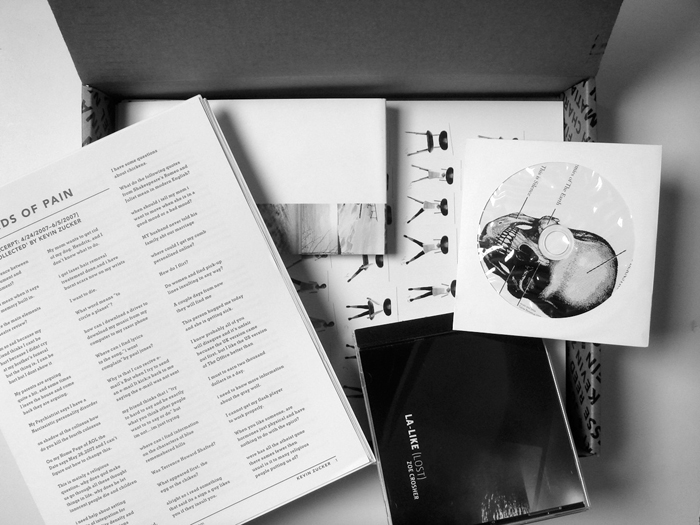

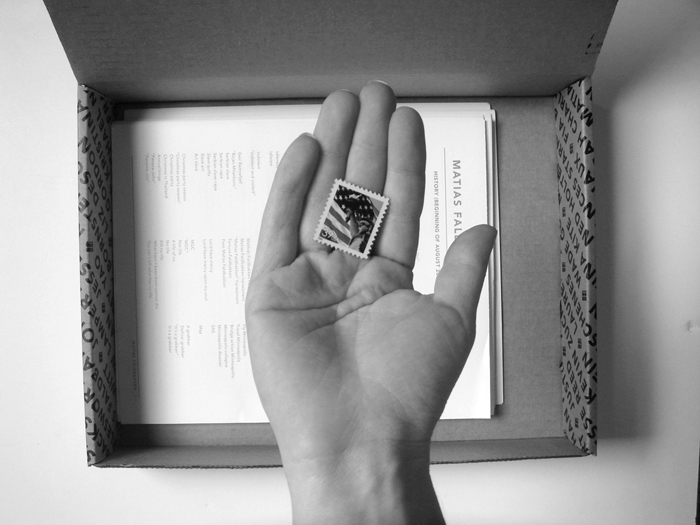

North Drive Press #4, 2007. Photos Courtesy Sara Greenberger Rafferty and Matt Keegan.

MK: It’s like having a great conversation with a friend. North Drive Press and the Etc. project were both driven by this idea of perpetual conversation, where the actual exhibition, project, or publication was something in flux.

FB: It’s not such a great idea to use the word collaboration for almost any relation.

MK: Well, it becomes something that’s used to talk about anything that involves more then one person.

FB: Yes, in the end, even Bush could be said to collaborate with the prisoners on Guantanamo Bay, as if something nice is going on. The word is even used by some curators who say that they are collaborating with artists.

MK: I think about Julie Ault and Martin Beck, and the way in which they’ve worked together over the years. In reading about and seeing some of their projects, it seems like they have a complex collaborative relationship that is not: “I added some red, you added some blue and then we have this new thing.”

FB: There is exchange, a fusion—there’s a new fruit.

North Drive Press #4, 2007. Photos Courtesy Sara Greenberger Rafferty and Matt Keegan.

MK: Yeah, that’s what I was trying to allude to earlier, the new fruit. It’s inherently a hybrid because the “you” and the “me” aren’t discernable. I think that synthesis is crucial. I would never say that North Drive Press is a collaborative project, because the contributors aren’t in dialogue with each other to determine what is produced. I would say that my co-editor for NDP#3 and #4, Sara Greenberger Rafferty, and North Drive Press’s art director Susan Barber and I work collaboratively because we have different ideas of what the project should be, and we interrogate each other in terms of the direction the project should move in. But, I wouldn’t say that there’s any collaborative quality that goes beyond that. Looking again at your NYFA web project, I think that it is as successful as it is because it avoids pigeonholing the multiple ways in which you work.

North Drive Press #4, 2007. Photos Courtesy Sara Greenberger Rafferty and Matt Keegan.

FB: Isn’t it our responsibility to use language precisely, or rather purposefully imprecisely?

MK: At the end of the day, the thing that I’m always certain about, in terms of a notion of collectivity, is the necessity for a full investment in your friends’ and peers’ ways of working. Because in addition to the importance of work being reviewed or exhibited and whatnot, I think that to really, truly be engaged with colleagues’ work, one has to be committed to engaging with that work over time, in a way that isn’t allowed or possible within say, an Artforum review or artist interview. Figuring out ways to work together or to do projects that facilitate that exchange are crucial, especially in New York, which is the place I know best, but where a commercial paradigm definitely hovers.

FB: To write is one of the ways to have exchange.

MK: I don’t know. What did you just write? (laughs)

FB: Nothing, just a thing that I remembered.

Fia Backström is an artist based in New York who is interested in questions of the image: its signification process, its social interrelations and the parameters of a program and an audience.

Matt Keegan is an artist and co-editor of North Drive Press who lives and works in New York.