Meanwhile, in Baghdad… and Black Is, Black Ain’t are two recent curatorial projects crafted by Renaissance Society curator Hamza Walker. Of the five exhibitions hosted by the Renaissance Society during the 2007-08 season, these two politically charged enterprises welcomingly distinguish themselves from the profusion of contemporary group shows and biennials that are organized to boost individual curator’s self-importance within the contemporary avant-garde. Walker’s curatorial undertakings opt instead for investigations into pressing, hard-hitting cultural debates such as the Iraq war or the paradox of race.

Walker uses his institution, an esteemed contemporary arts society founded in 1915 and situated on the 4th floor of Cobb Hall on the University of Chicago campus, as a platform for risky political postulates and prominent display of powerful, first-rate artworks. Modestly, Walker says that he is “taking the temperature of a discourse” when he organizes group shows. But his projects are unique in curatorial practice because he does so with an apparently egoless dedication to contemporary art and a conviction for examining uneasy truths.

Walker also organizes parallel exhibition programming that takes advantage of The Society’s affiliation with the University of Chicago and its built-in audience that is loyal to formidable cultural events. Take for example the public curriculum accompanying Black Is, Black Ain’t. The exhibition kicked off with a conversation between the Menil Collection’s Frank Sirmans and Walker, two dynamic curators who are responsible for shaping critical and curatorial discourse on the sticky issues surrounding race in the visual arts. Lectures titled “Race: Effects and Intents,” “An all new CHA?,” “The Black Eclectic…Revisited,” and “From the Moynihan Report to Obama’s Candidacy” graced the following weeks of the exhibition as did poetry readings and panel discussions comprised of distinguished artists and art historians such as Kerry James Marshall, Tyehimba Jess, Darby English, and Kym Pinder.

These events are correlative to the exhibition and not didactic or explanatory, functioning in a manner similar to Walker’s pithy essays that accompany every exhibition and are only analogous to the selection and configuration of artwork. The concurrent programming allows the curator to keep the relationship between art and curatorial practice neat and uncompromised. As a consummate steward of artistic practice and a committed cultural critic, Walker takes on projects that are bigger than curators and art institutions but never bigger than art itself. This puts him at odds with the ranks of contemporary curators who, infatuated with their own imaginations, regularly employ art as props. It also distinguishes him from the curatorial tastemakers who trade exclusively in reputations and commercial appeal.

Meanwhile, in Baghdad… included work by Adel Abidin, Walead Beshty, Matt Davis, Kenneth Goldsmith, Daniel Heyman, Jenny Holzer, Maryam Jafri, Jannis Kounellis, Ann Messner and Jonathan Monk. Comprised of a smaller group of artists than the breathier Black Is, Black Ain’t, this show was more equivocal toward its political thesis. Here Walker selected artist’s who represent very different conceptual and stylistic tracts for navigating the thematics of war. This imbued the exhibition with a welcome additional drift–that of examining the inherent qualities of rigorous contemporary political art.

The exhibition gets its title from Kenneth Goldsmith’s epic poem “The Weather.” At the opening reception, Goldsmith sat at an unadorned desk with a microphone in the corner of the Renaissance Society’s single-volume gallery reading from his poem. “The Weather” is culled from transcribing one-minute weather reports from an all-news radio station out of New York City for the course of one year—2003. In the spring of 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq. In response to the invasion the weathercasters presented their listening public with fifteen days of duel geographic weather updates: New York and Baghdad. “Battle field forecast: poor visibility.” “Sunshine and forty-four degrees in mid-town.” “Windstorms and sandstorms in the southern portion of the country.” “Favorable for military operations.” After the opening, the desk and microphone remained. A recording of Goldsmith’s poem played continuously, filling the exhibition space with the mundane backdrop of AM radio broadcasting. When pulled from their context and recited ceaselessly, Goldsmith’s appropriated one-minute weather reports evoke media perversions, brainwashing, and governmental propaganda. Yet “The Weather” in all of its political subtexts is foremost a poem. Its loyalties are directed at the vagaries of language.

Ann Messner’s offset tabloid was available free for gallery viewers. Displayed in boxes stacked high on a wooden palette, the black and white broadsheet anthologized professional dissenting voices published during the first three years of the war. Titled The Disasters of War (2005) it included photographs of flag draped coffins, soldiers with prosthetic legs, and iconic images of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. It also included a full bibliography and links to websites. Like Goldsmith, Messner’s appropriation derived project compressed streams of public information. It was a collection of voices by powerful political dissenters yet, unlike Goldsmith’s poem, it was artless. Only its title kept it on the literary side of journalism. This is the only work in the show that sat awkwardly between artwork and artifact, political activism and political art.

Matt Davis’ large Lambda print titled Trooper (2003) is a painterly composition depicting a fully outfitted combat trooper. Centrally located, the figure is repeated and enlarged several times creating a visual effect that communicated both physical and psychological intensity. Its collage appearance and faux painterly surface combined with a telescoping compositional device located it between Rauschenberg and psychedelia. Unsettling in its evocation of a detonating soldier, Davis’ trooper also echoed the political and military quagmire in Iraq.

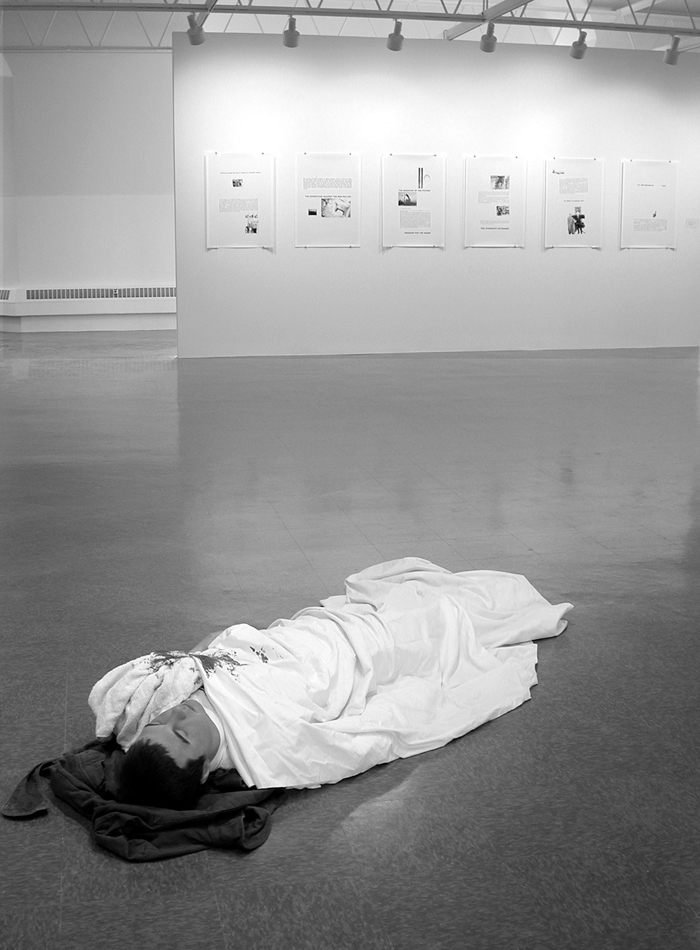

The most iconic and literal piece in the exhibition was Jonathan Monk’s Deadman (2006) with its convincing nod to classical sculpture. This life-size figure of a young man was laid out on the floor in the middle of the gallery. Draped with a bloodstained sheet, the figure’s verisimilitude was uncanny, not because of its realism to death but due to its reference to art. The principled largeness of portraying a fallen war hero and Western art’s fictional depictions of Socrates and Marat come to mind before the political rhetoric of “These Stripes Don’t Run,” or “Support Our Troops.”

Walead Beshty’s photographs are culled from the abandoned Iraq embassy in Berlin that was vacated during the first Gulf War. These large-scale, chromogenic prints document the embassy’s interior disarray. The negatives from which these prints originate were exposed to airport security x-ray machines, resulting in an overexposed, bleached appearance. These decolorized images are specters of transition and hauntingly prefigure the media images coming out of Iraq on a daily basis.

A more abstract image by Beshty titled Political Abstracts 1 (Library, Tschaikowskistrasse 17 Relative Color) (2006) documented a washy red liquid surface dripping with the pull of gravity. A darkroom experiment, a riff on colorfield painting or a photograph of the Embassy’s bloodied library wall; these are all potential readings of this image. Beshty’s practice is promiscuous and his photographs are arrogant and cynical, political and ridiculous, allegorical and formal. When asked about the exposed film during a panel discussion moderated by Walker, Beshty suggested that “the film continues to see,” a metaphysical response that thoroughly negates the military strategy of reconnaissance imaging.

Daniel Heyman’s eight dry point portraits depicting clumsy likenesses of tortured men from Abu Ghraib humanized these victims the way press reports and photographs cannot. Heyman also included these men’s date of birth and the date of their arrest in the background of his portraits. Scrawled around these figures are detailed statements describing their captivity and torture. For example, one print titled Our eyes were covered… (2005) states, “Our eyes were covered with plastic wrap and goggles…We were asked to undress and stay under the hot sun for hours, handcuffed…”

Maryam Jafri and Jenny Holzer’s projects expounded on the slippery employment of language, redaction, and official and unofficial statements in politics and warfare. In their work the fictitiousness of political conflict was made frightfully clear. Conversely, Jannis Kounellis’ three bed frames wrapped in strips of canvas soaked in red paint elicited visceral horrors that words cannot convey.

Unlike the metaphorical potential inherent in the majority of the artwork comprising Meanwhile, in Baghdad…,Walker’s exhibition essay “Mo Ri Xon” is specific, timely, and debatable. He contextualizes the work in the exhibition without explaining it and sometimes that means sounding like a political pundit. For example he writes in the concluding paragraph:

The much anticipated report from General Petreus did little to quell the suspicion that Iraq may have become a “quagmire,” a description inextricably linked to the war in Vietnam. Although Colin Powell early on called such comparisons “bizarre historical illusions,” given that there is no time frame for troop withdrawal, those “illusions” are probably looking a little too real. If anything, such a comparison has only gained in detail now that the rhetoric of “shock and awe” and “the winning hearts and minds” has been exposed as having been hopelessly naive.

Walker’s Black Is, Black Ain’t is titled after a phrase borrowed from Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man. The exhibition examined the negotiated positions of race since the mid ’90s. Debated positions such as inclusion, representationalism, and the exhausted rhetoric of diversity are volleyed about in this loquacious exhibition that sported the work of twenty-six black and non-black artists. Walker writes, “…This exhibition surveys a moment in which race is retained yet is simultaneously rejected.” Manifesting a paradox that maintains the cultural production of “blackness” and the idea that race is irrelevant is yet another risky proposition for a curator. But Walker once again takes on a weighty subject and succeeds because of his dedication to critical matters and his commitment to exhibiting strong works of art.

In his exhibition essay for Black Is, Black Ain’t, Walker unabashedly marches readers through a recent history to further confound the cultural conundrum of race:

With respect to African-Americans, the public discourse on race is hardly suffering for want of incidence. A constellation of arbitrary events from recent memory includes the Don Imus affair; the trial of the Jena Six; the NAACP’s staged of the “N” word; the questionable distribution of hurricane Katrina relief funds; “Straight Thuggin’ Ghetto Parties” at The University of Chicago (where fun purportedly comes to die, a 187, no doubt); the ironic revelation that Barack Obama and Dick Cheney are eighth cousins; the not so ironic revelation that Al Sharpton is the descendant of slaves owned by the family of the late senator Strom Thurmond; the Supreme Court’s striking down of school integration plans in Louisville and Seattle; and last but not least, Obama’s presidential candidacy. Our so-called “obsession” with race reflects an anxious optimism insofar as race relations are a monitor of social progress. The dream bequeathed us by the Civil Rights Movement of being able to disregard an individual’s race entirely is as cherished as any constitutional ideal. As Obama eloquently noted in what is now referred to simply as “The Speech,” this dream makes the pursuit of a more perfect union anything but an abstraction. Transcending race, however, has proven a somewhat paradoxical task, one fraught with contention as our efforts to become less race conscious serve to make us more race conscious.

Black Is, Black Ain’t could be broken down into several political arcs: artwork that examined the history of civil rights, artwork that employed black aesthetics (Walker characterizes this work as “soulful”), artwork that confounded skin color, artwork that addressed race and its connection to class, and finally artwork that engaged in the reification of race. Unlike the equivocal contributions to Meanwhile, in Baghdad… the work comprising Black Is, Black Ain’t was particular, argumentative, and contentious. Juxtapositions of works got raunchy. Alliances between pieces were established. It was a tension-filled exhibition complete with pitfalls and dangerous political fissures.

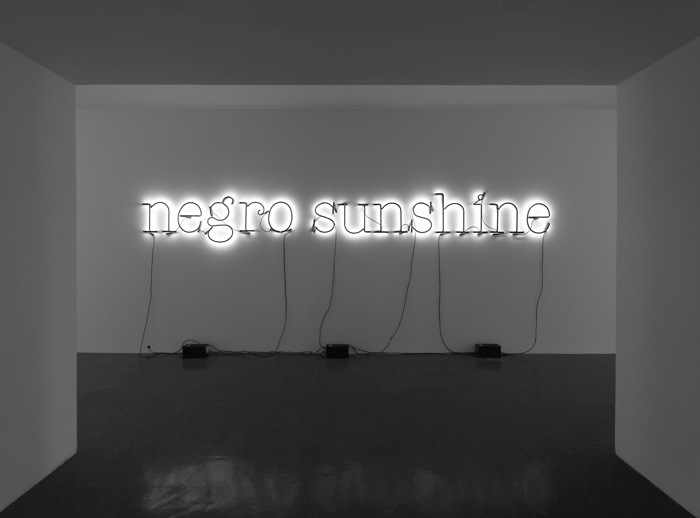

Glenn Ligon’s neon sign titled Warm Broad Glow (2005) illuminates the idiom Negro Sunshine. It was the ironical keynote that welcomed viewers at the entrance to The Renaissance Society’s vaulted exhibition space. It also stood in anxious opposition to David Levinthal’s series of Polaroids portraying single, black-face figurines. Uncomfortably familiar to Levinthal’s photographs was Hank Willis Thomas’s The Johnson Family (from the Unbranded series) (1981), an altered advertising image of an idealized black family–mother, father, and daughter–each beautiful, young, and smiling for the camera.

Paul D’Amato’s archival inkjet prints documenting Chicago’s notorious Robert Taylor homes and the Cabrini Green high-rise housing project, Rodney McMillian’s found overstuffed chair that is pathetically abject, and Robert Pruitt’s swags of gold chains all convincingly intertwine race and class. These obsequious objects and images also forcefully contrasted arresting photographic portraits by Andres Serrano. Serrano’s monumental picture titled Woman with Infant (1996) was awe-inspiring in its depiction of maternal affection. A studio portrait of a nude black woman cradling a white naked infant trumped all racial configurations with its depiction of human devotion and touch.

Black Is, Black Ain’t was a thorny collection of works that explored the cultural paradox of race while still being a collection of significant contemporary drawings, videos, sculptures, and photographs. This is what Walker does exceptionally well, making a curatorial practice out of exhibiting important art and exploring the cultural issues of the day. “Taking the temperature of discourse,”means that he is not fabricating a debate or inventing a quirky poetical framework to be illustrated by artworks. Unfortunately this kind of dedication to art and idea is unusual in contemporary curatorial practice. Curatorial practice has careened away from the platforming of art and ideas to become its own type of relational art practice. In many cases, the curator has become the artist.

The mean-spirited squabbling sponsored by Artforum this past year between Robert Storr and his foes, Okwui Enwezor, Francesco Bonami, and Jessica Morgan, is a perfect illustration of this curatorial incertitude. Storr wrote in a rebuttal letter to his critics in the January 2008 issue “In truth, the problem for those who have been the most categorical in their attacks is that the 52nd Biennale actually took a position, or an interconnected combination of positions, that disputed their own.” There can be no dispute in Walker’s curatorial efforts regarding the Iraq War or the contradictions of race because these issues are not his positions. They are our truths.

Michelle Grabner is an artist and writer living in Oak Park, IL, where she runs The Suburban, an artist project space, with her husband Brad Killam. She is a Professor in the Painting and Drawing Department at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.