One of the most anticipated exhibitions of the spring is Marina Abramović’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Marina Abramović : The Artist is Present surveys the entirety of Abramović’s four-decade career as a performance artist from her early Rhythm series in the 1970s to her video installation/ performance Balkan Baroque (1997) at the Venice Biennale, to her most recent projects. The works all address duration, physical stamina, myth, and intensive states of mind such as attentiveness and focus. Abramović frequently discusses her work as ritual, as attempts to purify her actions and to become attentive to her own state of mind, which she believes can change the “energy field” (her phrase) of the space her viewers collectively occupy. It is towards this point that she conceives of her work as a whole: “All my work is about emptying the mind, to come to a state of nonthinking.”1 However, many of Abramović’s works are also bound up in her own biography, so that even as she was studying the nomadic and spiritual aspects of Tibetan and Australian Aboriginal cultures, for example, she conducted The Great Wall Walk (1998/2008). In The Great Wall Walk, she and her partner and collaborator of twelve-years Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysipen) each began at separate ends of the Great Wall of China, a “metaphysical structure” in Abramović’s mind, and walked over 2000 kilometers until they met in the middle, only to dissolve their relationship and go their separate ways.

Marina Abramović, installation view of Balkan Baroque at the Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo by Jason Mandella. Balkan Baroque was originally performed in 1997 for four days, six hours each day at the 47th Venice Biennale. Three-channel video (color, sound), cow bones, copper sinks and tub filled with black water, bucket, soap, metal brush, dress stained with blood. 24:47 min. © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy Marina Abramović and Sean Kelly Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

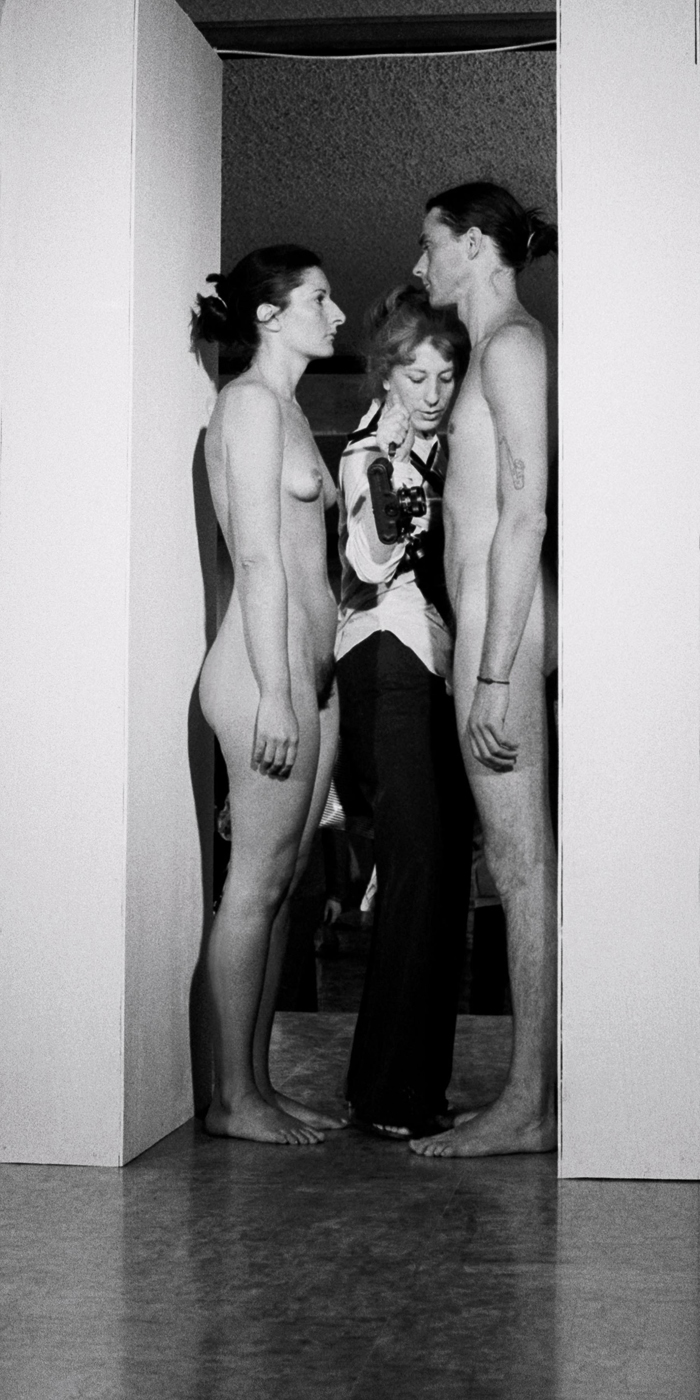

At MoMA, the galleries are nearly overfilled with all types of notes and documentation of her performances: films, objects, photographs, written matter and, most notably, “reperformances” by other artists of five of Abramović’s now canonical works–two completed with Ulay and three done by her alone. One example, which immediately heightened the spectacle of the entire event, was the reperformance of Imponderabilia (1977), in which audience members passed between the impassive nude bodies of two artists who stand facing each other in the frame of a door, indifferent to passing visitors. In addition, Abramovic’ performs a “new” work entitled The Artist is Present, which she enacts for the entirety of the retrospective’s run. This “new” work is actually a “reperformance” of Nightsea Crossing (1981-1987), which she and Ulay performed twenty-two times over that period of time. Rather than sitting across a table staring at one individual (as she did in Nightsea Crossing), in The Artist is Present (2010) Abramovic’ sits at a minimal wooden table with two chairs awaiting museum visitors, one at a time, who sit opposite her so that they can blankly stare at each other for however long the visitor can endure. (Abramovic’ does not flinch or smile. Even unplanned interruptions by other artists who have tried to commandeer the event have not broken her.2

Marina Abramović and Ulay, Imponderabilia. Originally performed in 1977 for 90 min. Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna. Still from 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound). 52:16 min. © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy Marina Abramović and Sean Kelly Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Reperformed continuously in shifts throughout the exhibition Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present at MoMA, 2010.

The concept of “reperformance” has generated much discussion in the art world, especially when one considers the current reassessment of the discipline, including its prominence at the 2009 Venice Biennale and the interest generated by Tino Sehgal, whose “constructed situations” have done much to reinvest the discourse of performance art. Sehgal’s approach has been to sell the rights to his performances to art institutions such as MoMA, which purchased Kiss (2004). In Kiss performers slowly move through choreography specified by Sehgal, embracing each other in poses that occasionally resemble couples in historical paintings. In interviews and discussions coinciding with the opening of the retrospective, Abramović argues that reperformance is the best way to deal with the history of performance art and the accompanying demands of institutions. She contends that it is a way to take responsibility, or, in her words, “to take charge of the history of performance.”3 Abramović asserts that it is necessary for these works to be “reperformed” not to recreate or negate their initial historical, cultural, or political context, but rather as a way to keep the gesture of the work vital for practicing artists and not just for art institutions.

Installation view of Marina Abramović’s performance The Artist Is Present at the Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo: Scott Rudd. For her longest solo piece to date, Abramović sat in silence at a table in the museum’s Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium during public hours, passively inviting visitors to take the seat across from her for as long as they chose within the timeframe of the museum’s hours of operation. Although she did not respond, participation by museum visitors completed the piece and allowed them to have a personal experience with the artist and the artwork. © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy Marina Abramović and Sean Kelly Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It is important to note that Abramović is not alone in supporting this idea, but neither is she without opponents. The concept of reperformance is attractive to galleries and museum curators who see how reperformance can offer a more compelling experience than photo documentation or props. However, this concept is not simply an institutional ploy. For example, in 2003, Yoko Ono recreated her famous performance Cut Piece in Paris as a way to foreground the correspondence she saw between the geopolitical situation in the mid 1960s and the first years of the reassertion of American global hegemony in the aftermath of 9/11. Joan Jonas, however, takes the opposite position. She adamantly contends that “there’s never a way that you could repeat the original thing; it just can’t be done.”4 Jonas is keen to remind us of the socio-cultural context in which performance art arose in the 1960s and 1970s, wherein a dominant aspect of the discourse was to challenge commodity-status of the artwork and its institutional, economic structure. It is true that the sharpness of this critical position has become dull and blunted as performance art has become an accepted form of artistic practice. Nonetheless, it does not follow that protecting the subjective memory or the supposed integrity of the original intention of these performance pieces either heightens their politics or encourages any form of contemporary critical practice. The question remains: What are artists and historians to do with this history? What relations must we construct between this disparate, contentious history and future art practice? It is clear that for both Ono and Abramović it is not simply a question of repeating “the original thing,” an assertion that misses how and why a repetition is not a limitation but a creative possibility. In theater this is obviously the case. No one claims that a reperformance of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, for instance, is an attempt to recapture the “original thing,” which never existed anyhow except as a script, as a potentiality. Each reperformance is a repetition; each repetition is not simply different, but it is difference as such. Difference and repetition involve tension and risk, but also offer new possibilities, new combinations, and new affects.

A willingness to make this wager is what sets Abramović apart on this front. It began with her reperformances of iconic works by other artists in 2005 with Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim Museum, in which she reperformed Vito Acconci’s Seedbed (1972) and Joseph Beuys’s How To Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), as well as other works by Gina Pane, Valie Export, and Bruce Nauman. The performances also included Abramović repeating her own Lips of Thomas (1975) and creating a new piece Entering the Other Side (2005). This set of reperformances was neither simply a process of excising the referent piece from its originary context; nor was it only a means to appropriate these earlier performances as Abramović’s own. The referent works are not authorities to be cited. Instead, they are paradigms, literally things beside themselves, doubled, caught in a process of becoming other in order to survive. Each work, including Abramović’s own, is a repetition, an encore, that is always different and thus part of an infinite series to come.

Marina Abramović, Seven Easy Pieces. Performed in 2005 for seven consecutive days for seven hours each day at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Seven-channel video (color, sound), seven hours. Day six: Marina Abramović Lips of Thomas, originally performed for two hours in 1975 at Galerie Krinzinger, Innsbruck. Photo: Attilio Maranzano. © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy Marina Abramović and Sean Kelly Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Instances of the strength of reperformance are evident in the retrospective itself. The actual performances taking place throughout the exhibition are certainly the focus of attention. To discern the subtleties of animate and inanimate in works such as Nude with Skeleton (2002/2005) and Point of Contact (1980) requires an intensity of focus that the sheer size of the gallery rooms and the number of people make almost impossible to accomplish. Nevertheless, the acts of concentration and stamina exhibited by the artists reperforming Abramović’s works demonstrate precisely how each individual artist undergoes a transformation and, in that particular duration, becomes the work, until she or he is replaced by another performer. In the reperformances, Abramović seems simultaneously present and absent. It is no longer simply her work, as now she is only part of a series of performers and performances. In contrast, some works that were compelling in their initial presentation have lost much in their retrospective afterlives. Abramović’s House with an Ocean View (2002), a brilliant ascetic ritualization of the everyday conducted by her for twelve days in three rooms built in the Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, has been reduced to the three spaces and the objects in them. What is missing here is a performer, though not necessarily Abramović . The work is not specifically about her as much as it is about habits, ritual, deprivation, purification, and privacy. The strength of the work is not the set design alone, even though Abramović did leave it on display after her living installation ended in 2002; instead, it is the situation and the transient images made by the performer’s actions, tasks, and changing physical appearance. To see the stage set without the performer–any performer–is like being a voyeur of an empty apartment.

My experience of the exhibition as a whole reminded me that performance, even in its subtlest forms, concerns intimacy and time. The challenge Abramović’s work consistently offers, from violent, sadomasochistic pieces like Rhythm 0 (1974) to the oddly sublime, such as Nude with Skeleton, is intimacy–the ways in which it is avoided and denied, the ways in which it becomes possible only when one is exhausted. Abramović’s physical presence at the retrospective is undoubtedly a highlight. In fact, with her being situated on the floor below the galleries housing the retrospective, most people witness, and in some cases participate in, the “reperformance” with Abramović herself before venturing upstairs to see the exhibition. On one hand, the title The Artist is Present leads one to suspect that this work, and perhaps each and every work, is just another narcissistic piece of an elaborately constructed artistic biography. But the experience of the work counters this suspicion. People who have sat across from Abramović and experienced the work have generated a steady stream of comments on blogs and in various articles. These accounts repeat certain responses, such as not having the stamina or desire to stare stonily at Abramović as hundreds of spectators observe and comment. Aside from these expected responses, another, more interesting, observation centers on intimacy and the sense of time. The most poetic comment that I’ve read comes from a thirty-two year old man named Dan Visel, who explained: “Time was passing, but I couldn’t tell. The overwhelming feeling I had was that you think you can understand a person just by looking at them, but when you look at them over a long period of time, you understand how impossible that is. I felt connected, but I don’t know how far the connection goes.”5 Losing all perception of the passage of time as it relates to the (un-) knowability of another person, especially if only by looking at his or her face, suggests that to understand fully Abramović’s best pieces such as Relation in Time (1977) or Rest Energy (1980) is to comprehend that performance is the becoming-image of a body. This becoming-image, however, happens only when one passes through tiredness and becomes exhausted.6

Marina Abramović and Ulay, Relation in Time. Originally performed at 1977 for 17 hours at Studio G7, Bologna. Still from 16 mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 50:33 min. © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy Marina Abramović and Sean Kelly Gallery / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Reperformed continuously in shifts throughout the exhibition Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present at MoMA, 2010.

Exhaustion is an event, a becoming-other than runs the risk of presence not for oneself, but for another. Exhaustion reveals the transformative potentiality of an image, which is a fortuitous and precarious opening to alterity, to another temporality, another becoming. Each and every image transmits an opening that is always an encore that re-presents the face of the Other as a radical intimacy. Near the end of his life Gilles Deleuze wrote an essay entitled “The Exhausted,” in which he said, “the exhausted is the exhaustive, the dried up, the extenuated, and the dissipated…it maintains a relationship with language in its entirety, but rises up or stretches out in its holes, its gaps, or its silences.”7 This outside of language is the exhausted, which is a domain of the image because an image is “not defined by the sublimity of its content but by…the force it mobilizes to create a void or to bore holes, to loosen the grip of words…a small, alogical, amnesiac, and almost aphasic image, sometimes standing in the void, sometimes shivering in the open.”8 To create such an image is to open a space in which a sensation of time slows, dissipating the image, revealing its power to trace a boundary between said and seen, self and other, to open an immanent presence:

An image, inasmuch as it stands in the void outside space, and also apart from words, stories, and memories, accumulates a fantastic potential energy, which it detonates by dissipating itself. What counts in the image is not its meager content, but the energy–mad and ready to explode–that it has harnessed, which is why images never last very long.9

Images dissipate, but in doing so they leave a sonorous line that resonates. To create a single image, one that resonates, is to reperform, to repeat, to echo, to go on, but with an intimate difference. Time and again.

Jae Emerling teaches art history at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. He is the author of Theory for Art History and is currently at work on a book about photography and critical theory to be published by Routledge in 2011.