This conversation is the first in a series in which pairs of artists who work closely together are asked to meditate on “medium.”

The idea came out of my own frustration with the oft-asked question, “What kind of work do you make?” As we are now mired in a field of fragmented and ever elusive art practices, and accepting that there may never be another defining movement of this generation or any other one, the difficulty that some of us have in answering that question becomes sort of interesting. Naively perhaps, I imagine in Modern times the answer was simple (“I Paint.” “I Sculpt.” “I make Photographs.”) And although there are many new terms floating about to describe new approaches to making art, none of them seem to help with answering of the question. (“I make Relational Aesthetics.” “I New Genre.”) So I started to think about how we think about the work that we make, and what makes up that work.

The more one investigates the word “medium,” the more elusive it becomes. A quick Google of its definitions further mucks it up. Medium is “a means or instrumentality for storing or communicating information,” “a state that is intermediate between extremes; a middle position,” “someone who serves as an intermediary between the living and the dead,” and/or “the surrounding environment.” I might settle for the somewhat satisfying “an intervening substance through which something is achieved,” but it is not always easy to name that which intervenes.

In a recent essay entitled “Two Moments from the Post-Medium Condition,” Rosalind Krauss suggests that medium is more accurately described as a “technical support.” She defers to this term “as a way of warding off the unwanted positivism of the term medium’ which, in most readers’ minds, refers to the specific material support for a traditional aesthetic genre.”1 (This leads her to surmise that Ed Ruscha’s medium is cars and that Sophie Calle’s is the “journalist’s report.”) But what if we need to take back medium, as a refuge from the “strategies” or “movements” that now seem to condemn or confine work? How might the term medium, with all its history and baggage, be useful today?

The artists contributing to this series all work in substances that lie somewhere in between or outside of an easy definition: the stuff of their work is always already an investigation of its own material while resisting identification with any one particular genre, movement, support, subject, strategy, impulse, or medium.

The following conversation took place between Althea Thauberger, Kerry Tribe and Melanie O’Brian. Althea Thauberger is an artist based primarily in Vancouver, BC. Kerry Tribe is an artist who splits her time between Los Angeles and Berlin. Melanie O’Brian is a curator, writer and is currently the director of Artspeak, a nonprofit gallery in Vancouver, BC. The three are friends and have been in conversation about their practices since 2003. In addition, Thauberger and Tribe have worked closely on one another’s projects since that time. Tribe will have a solo exhibition at Artspeak in December of 2007.

-Shana Lutker

Kerry Tribe, Production stills from Episode, 2006. Color video with sound, 30:00 minutes.

Kerry Tribe, Production stills from Episode, 2006. Color video with sound, 30:00 minutes.

Melanie O’Brian: In the hopes of instigating a lively conversation about the notion of “medium,” I might start with a shorthand definition of the term. Medium could mean an interface, a means of communication, a substance, a platform, or a tool of cultivation. Medium is often an easy way for a practice to be approached; a practice can be simply defined through its mode of communication such as photography or sculpture. There are limitations to what the notion of medium can tell us about a practice but this presents the opportunity to widen the discussion.

Both of you have been described as video artists. Althea, your work might be also be described as performance, community collaboration, music, and photography. Kerry, your work has been categorized as collaborative, photographic, and installation-based. Your use of a variety of media might prompt someone to categorize your practices as interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, or under the rubric of “relational aesthetics.” However, there seems to be an inherent inadequacy in these terms with regards to the specificity of process (which is often in the case of your practices crucial to the work’s subject). In Kerry’s work the use of video (and film) implicates its own histories and structures, and that becomes part of the subject matter–for example the repeated “retakes” in Near Miss (2005).

Maybe we can begin by taking the notion of medium and turning it toward a discussion of process. Kerry, could you discuss the way you work with the structural elements of media?

Kerry Tribe: I’ve never really felt comfortable applying the term “video artist” to myself, in part simply because it doesn’t account for projects that aren’t video-based (I’ve made a couple of films, a book, some sound works among other things.) But also, frankly, because I’ve always had this image in my mind of what video art looks like and I kind of hate it. I’d like to think I’m more sophisticated than such wholesale dismissals, but the truth is, when I hear “video art” I either think of art students mutilating themselves in front of cameras set up in their studios, or of pretty but meaningless shapes drifting across the wall to ambient audio tones, or of watchable little shorts that have all the production values of a Hollywood movie with none of the narrative or cathartic pay-off. That probably sounds incredibly cynical, and of course there’s good work being made in the medium, but I still harbor stereotypes. Actually, when you think about it, it’s not surprising that a great deal of the “video art” out there can be categorized into one of those three models, each of which, in its own way, continues a major strain in the history of the medium. The history of video art includes lots of works that capitalized on the ability of the video camera to (instantaneously) index bodies and events, formal experiments that pushed the medium’s imaging capacity, and projects that appropriated the language of film and television.

I think that’s where your question of structure comes in: what are some of the inherent structural qualities of, say, film, video and installation, and how can they best be mined? In my case, when I have an idea for a project it usually starts with a simultaneous notion of some formal structure as a kind of container for what you might call the “content,” though of course to separate form and content is only useful semantically. As the project evolves, the demands of one inevitably shape the choices available for the other. For example, when I got the idea for Here & Elsewhere (2002), I knew I wanted to use moving camera shots and two side-by-side projections to create particular phenomenological effects around the vertical seam where the two images would meet. And I knew that those effects, in turn, could serve as a kind of analog for ideas that could arise in the interview around which the project’s narrative revolved. With Episode (2006), which I made after living in Berlin for nine months, I was thinking about how in Germany there’s this tradition of the news and culture talk show that provides a way of rationally “getting to the bottom” of controversial contemporary events. I was curious to see what might happen if I were to plug radically different “content” into that pre-existing formulaic structure.

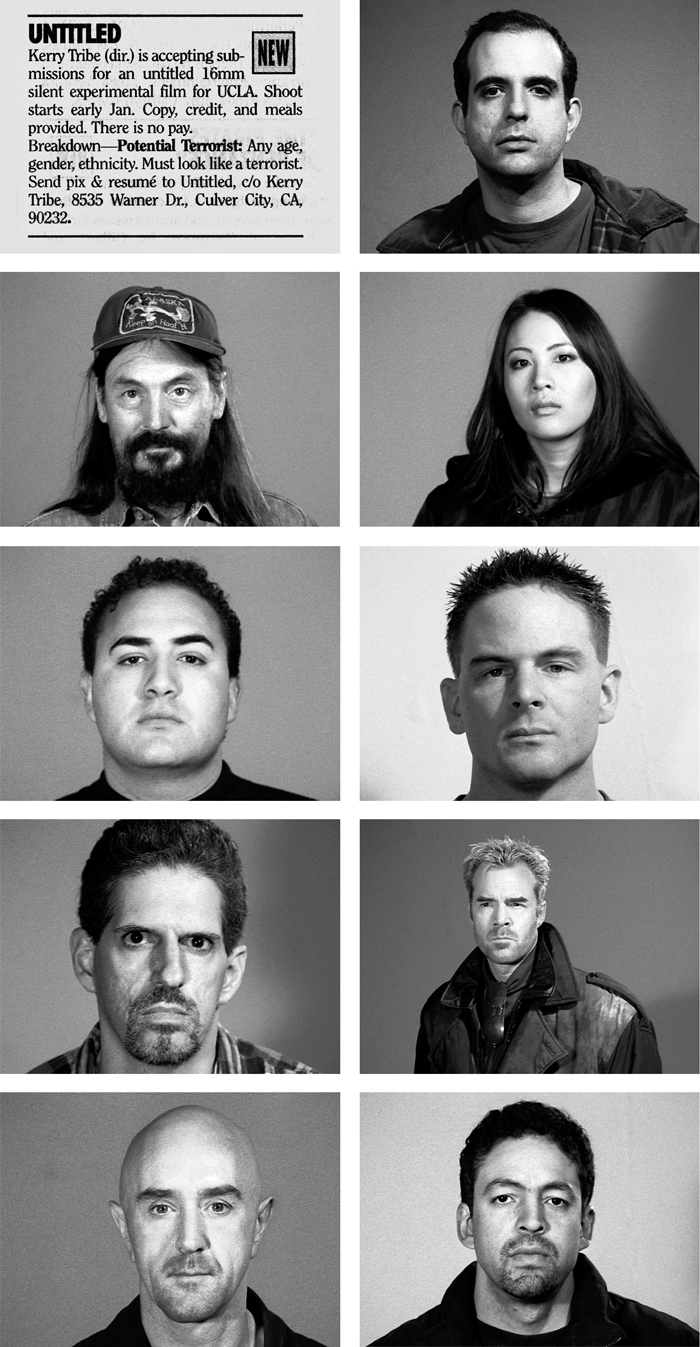

Which gets to the second part of your question. In terms of process, I think of myself as an editor or director more than as an author. In most, though certainly not all, of my work, the artist basically functions as the springboard and the glue. (I think this holds true for Althea as well.) Other people do all the hard work! Even with this article, I was sure I couldn’t think of anything to say about “medium” until you came along and started a conversation. I also think of it as a propositional practice: most of the projects start out with the idea “what would happen if…” What would happen if I were to try to find actors to play me? What would happen if I ran a casting call and shot screen tests for the role of a terrorist? How do people imagine LA and how would they draw it if you gave them a pen and paper? What would happen if I hired a film and special effects crew to try to re-make a memory?

MO: Althea, how would you describe how you work with media, not in particular media? For example, Songstress (2001/02), not afraid to die (2001) and Northern (2005) are works structured around the physical and durational lengths of the rolls of film used to make them.

Althea Thauberger: It’s difficult for me to separate media from subject matter, from concept, or from form. My projects usually begin with an image or sense of something that feels important. Then the way of bringing it into being implicates its various dimensions (media, subject matter(s), etc.) that overlap upon each other and can’t be understood separately. These “pre-images” are always transformed by the processes of coming into being–by what could be called media, by the people I work with, by how I plan their display. But I think something of their initial sense usually remains. Before I made Songstress, for instance, I imagined a number of young women, all singing simultaneously (but in isolation) about their subjectivities as if they were the only people in the world, and as if the only thing that ever happened in the world was that young women sing out about their subjectivities. The women were all of us, and all of us were young women. When we made the films, single 100-foot rolls of 16mm film became a kind of isolating container–each performance had to fit within the 3-minute duration of a single take. Through their actions, some of the performers (perhaps inadvertently) challenge the containment. These awkward moments are the powerful ones.

MO: Your responses prompted me to revisit the catalogue for Video Acts: Single Channel Works from the Collections of Pamela and Richard Kramlick and New Art Trust (PS1, 2001). The focus for the show was the relationship between video and performance, especially the body caught on camera, and how this has evolved over the last three to four decades.

You don’t use yourselves in your works (except for in a few rare cases such as Kerry’s Episode [2006] or Althea’s Oh Canada [2001]), but the subject of performance is undeniable. Maybe we should further discuss performance as a medium, which might make you cringe as much as “video art” does. Historically, video made the (temporally and spatially distant) viewer a witness to a performance. In a way, this forces us right back to a primary discussion of the legacy of conceptualism (1960s on) and its use of performance, language, photography, film. Its recognition of its own physical context and substance presented a critique of the institutions or institutional ideas that condition experience in the process of signification. This self-criticality, questioning of authorship, audience, etc. is still entirely relevant to a discussion of medium and both your practices.

KT: I don’t appear in my work because I hate seeing myself on film, couldn’t act my way out of a bag, and I don’t think I could handle being both sides of the camera at once. When I get friends or strangers to participate in projects, they’re usually being asked to do things they’re not especially well-equipped to do (like draw maps or make bird-calls) and I think it’s actually the “flaws” in their performances–the extent to which what they do diverges from our expectations–that give the work room to breath. Whenever I work with actors, they’re playing themselves (actors acting) as much as they’re playing whomever they’ve been hired to play (my mother, or a terrorist, or whatever). My desire to keep these two positions (actor / character) ping pong-ing stems in part from the way performance artists have traditionally used film and video, and the way narrative filmmakers have traditionally used performers. In the former, there’s an expectation of authenticity and immediacy that would seem to suggest that the mediating substrate just gets in the way. (Think Chris Burden’s Documentation of Selected Works, 1971-1974, a tape introduced by an extreme close up of Burden explaining why the documentation doesn’t do the works justice.) In the latter, it’s the performer who is expected to become transparent so viewers can identify exclusively with their character. For some reason, I’ve never been particularly good at that. My husband says I have an over-active empathy drive, meaning that I always end up identifying where I’m not supposed to (like with the actor). This makes it very hard for me to watch bad performances or go to the theatre. I worry about the people on stage when there’s no way to yell, “Cut!” Anyway, what minimalism, conceptualism, and certain avant-garde film practices added to the picture was the Brechtian possibility of turning the viewer’s awareness towards the context around the action, the negative space of the gallery, and especially towards their own subjective viewing position.

One of the things I love about Althea’s work is the way she uses conceptual armatures as starting points but allows a lot of room for interpretation by the people she enlists. It’s a welcome relief from the airless perfection of strict conceptualists. She invites singing, and emotion, and mistakes into the work. This is another form of the breathing room I mentioned before.

MO: When Klaus Biesenbach asked Joan Jonas how the medium itself informed and influenced the work, she replied: “I never saw a major difference between a poem, a sculpture, a film, or a dance. A gesture has the same weight as a drawing: draw erase, draw erase–memory.”2

Althea, how did you come to performance as a medium in your work? Has your understanding of it changed as your work has developed?

AT: When I was a tree-planter, long before I started art school, I started a yearly performance event (rather unremarkably) called Poetry Night. It was held during a party in the camp. Each planter had to take a turn presenting a poem, song, speech or skit of his or her own invention. After living and working for a season in severe wilderness conditions, people were often a little nutty and knew each other more intimately than they would have preferred. Imagine an abject scene with a group of scruffy twenty-somethings drinking heavily and entertaining themselves with performances about themselves and each other. These events were painful and hilarious and transformational in the way that the best art is transformational. They were totally site and community specific and changed my ideas of what a performance could be.

I appreciate the way Joan Jonas speaks of the temporality of gesture. Giorgio Agamben identifies gesture as making visible the human state of “being-in-a-medium,” opening up an “ethical dimension.”3 We now can’t understand art as separate from the gesture of bringing it into being. Although that might seem overly obvious, it could relate to the way we work with others, for example Kerry’s gesture of asking artists to make bird calls or my gesture of working with strangers to spell words with their bodies.

KT: Do you think you could call “collaboration” a medium?

AT: No.

KT: Right…I guess it’s what you’d call a “strategy.” And “Relational Aesthetics” is more a “set of practices,” or maybe a “movement.” Or just an essay.

AT: Ha, ha. Though for me, “collaboration” is more a process than a “strategy.” I associate the latter with a calculatedness that I don’t identify with. Although they can be discursively useful, I’m wary of terms like “Relational Aesthetics” and “Community Collaboration.” They can limit work and put it in the past.

KT: Thinking more literally about the notion of medium per se, I do think it’s significant that we both work pretty much exclusively with indexical media. Inevitably all our works offer some evidentiary truth about the world outside, regardless of how scripted the projects are. Would you agree? I also think it’s worth noting that a lot our projects effectively produce what you might provisionally call “ethnographic archives,” albeit ones that are pretty wonky…an archive of tree planters, of old people living in Florida, of young German social servants, of actors who think they look like terrorists…

Kerry Tribe, Casting notice and film stills from Untitled (Potential Terrorist), 2002. 16mm silent black and white film, 30:00 minutes.

AT: …Or of artists who make birdcalls, or military wives who live in a San Diego military housing complex… We both know that ethnographic impulses are totally implicated in the history of photography, but what about the impulse, as artists, to take this up again and again? I do agree with Kerry’s point about proposing truth value. Using ethnography together with theatre and fiction reminds me of the writing of Michael Taussig. Although he is an anthropologist, I think his way of working is also like an artist’s. My understanding of index in my work includes not just photographic images that are physically connected to their referent though light, but also the way participants mark projects with their experiences and ideas and bodies. I have come to think that it’s like working with direct experience itself, ironically, through its mediation. The way we–the big “we” who inhabit this moment and place–are dissociated from “that which presents itself to our experience” makes an urgency that I think you and I are responding to by working in this way…perhaps through some combination of defining the shape of that distance and trying to overcome it.

MO: Why do you choose to present some works as primarily experiential performances, or primarily as video, etc.?

AT: I don’t think of them as being so different. The works take the form that they need to. The performances may more intensely bring viewers and subjects into contact with one another (and also give the subjects the opportunity to also be viewers) but they do privilege “the image” as part of the experience of spectatorship.

MO: Indexical media including photography, film, and video have a special relationship to individual and collective memory. Personal and cultural memory can be identified as central themes in your work (along with their inverse: the lack of memory, or historical amnesia). How do you understand your choices of media with respect to these themes?

KT: Photographic media (including video) and the captioning or voice-over that accompanies it are how we know that things actually happen in the world. Of course, images can create memories (and make histories), and can certainly over-write the memories that might otherwise exist. Ask anyone outside New York City what they remember of September 11 and they’re bound to describe an experience with a television. I’ve become increasingly interested in things that don’t get caught on film (or tape) and how we know those have happened, and also in the ways that photographic media can undermine our linear understanding of time. To return to the example of September 11, I remember seeing Chantal Akerman’s “News From Home” (1976) a few months after the World Trade Center collapsed. The final, very long shot of that film was made from a camera stationed on the Staten Island Ferry as it pulls away from lower Manhattan. If I remember correctly, it’s raining lightly, and the city is a desolate blur of gray steel and concrete. It’s only after several minutes of pulling out from the city that we realize what we’ve been looking at all along: the World Trade Center, decades before anyone had imagined its destruction. For me, this was the best example I’d encountered yet of the “future perfect tense” that photography manifests, and that Roland Barthes so beautifully describes: the past as an event in the future, the presence of a future absence.

MO: Memory is actually a theme in both of your practices–specifically through reenactment. In both Kerry’s Near Miss (2005) and Althea’s A Memory Lasts Forever (2004), the medium is deployed to investigate a memory, albeit through different methods and avenues. Film and video is used in the construction of linear/narrative time –and creates a complexity and tension around the temporality of the memory, the viewer’s experience, the notions of “authentic” and fictional or scripted.

KT: This relationship between subjective memory and how it might be objectively represented is at the core of most of my recent work. Near Miss for example, is essentially an attempt to re-enact on film a relatively insignificant event that happened to me about fifteen years ago (essentially I lost control of a car during a nighttime blizzard). To make the film, I had to describe the choreography of that original event countless times to roughly a dozen members of the film’s crew. In the end, three similar “takes” separated by pauses of black constitute the 35mm film–none is ultimately privileged, and a lot of viewers walk out before they’ve seen them all. When the work is exhibited, I also include a textual description of the event as recollected by a member of the crew. Each crew member’s “take” on the memory inevitably diverges from the way I remember it (and my version is never included), and with each exhibition, a different crew member’s version is included. So a viewer who saw the work in two different shows would likely come away with two slightly different understandings of what took place. To be perfectly honest, I don’t think I remember what originally took place…the memory of making the film is much stronger. It’s wiped out the past.

AT: But you did have a strong sense of the original experience during the production of the work. I will always remember when you described to the crew the phenomenological effect you were trying to accomplish. They almost became conceptual conspirators in the work.

When I think about memory in a broad way, I think that we educated Westerners are in a unique position to learn from histories (leisure time, access to information in unprecedented ways) but in general the opposite seems to be happening. Instead of reflecting, we are ignoring histories and the marks we are putting on the world that will determine the future–our roles in a “future perfect” if you will. Personal mythology trumps cultural memory.

Kerry, I think your recent projects reflect this. In Near Miss, when the car spins out, all physical and spatial points of reference disappear. I think you wanted us to feel what you felt: that total disorientation. Or perhaps you wanted to represent what it feels like to be outside representation. You mythologize not yourself, but a poetic and metaphorically significant experience–of perhaps being “free” for a moment

A Memory Lasts Forever is also a collaborative, serial re-enactment of a personal memory. I didn’t expect viewers to feel what I felt as such, but I think the “authenticity” is conveyed through the performers, and how they occasionally puncture the project’s structure. The basic story was that four teenaged girlfriends have to confront the death of a family pet when they are “illicitly” drunk. They then pray together. The performances were shot poolside, in a suburban back yard, by a video crew who were accustomed to taping amateur stage performances. It was recorded in real time, so that the video has a 1:1 temporal relationship with the performance. In personal terms I was interested in the pain of the memory and its absurdity. In broader terms, I was sort of awkwardly imagining the story as a post 9-11 allegory of North American culture (responding to large scale tragedy for the first time, the turns towards religiosity or fundamentalism).

Althea Thauberger, Production still from Zivildienst ≠ Kunstprojekt (Social Service ≠ Artproject), 2006. Collaborative performance and video, 18:00 minutes. Courtesy John Connelly Presents, New York.

MO: Althea, you have commented that social contexts could also be considered media. What do you mean?

AT: In this case, I was thinking of media as “stuff the work is made of,” but maybe it’s not the best word. As we all know, standing in a gallery with some other people while considering an artwork is a social context. What if how a viewer decides to position him/herself critically and emotionally with regards to the work is social and tangibly part of “the stuff of the work?” To me, these questions have implications in how we choose to be spectators of others and the world. This is what I meant.

MO: Perhaps this is a good place to readdress performance, audience and the experiential, particularly the emotional, in your work. For me, as a viewer, there is identification with the subjects that could be described off-handedly as poignant and excruciating. Althea, I’m thinking of Songstress and A Memory Lasts Forever. I am wary to go too far here because it’s personal, but my reaction is then watched by other viewers who may, or more importantly, may not identify the same way. I feel self-conscious getting drawn into the work, abandoning myself to it, and it’s the other viewers and the gallery context that pulls me back into a state of self-awareness. Indeed, a live performance would function in the same way.

AT: It’s great that you describe this. People have told me in private of similar reactions, but critics have been reluctant to write about it, I guess because as you say, the reactions are personal. Or maybe make them feel vulnerable.

MO: Maybe the uncertainty this injects into the gallery experience could be understood as a kind of institutional critique. What are your thoughts about how institutional critique might operate in your work?

AT: I’d say a critical awareness of contexts around art is a given, and is one of a mesh of considerations. I would guess that the same is true for many artists working now. The thing is, at their best, contemporary art galleries are some of the few places we have left in the world to be presented with radical meaning. I believe in galleries, even when I am discouraged about what I often see in them.

KT: I think good artists are sensitive to the power dynamics surrounding the production and exhibition of contemporary art, so I don’t have a lot of use for the term anymore.

MO: If the term “institutional critique” is already anachronistic, what about “site specificity?” Your practices consider site beyond physical location and understand it more as a “discursive vector” (in Miwon Kwon’s terms.) Do you think this idea of a discursive site might offer a way around the limitations imposed by notions of medium?

AT: Absolutely, but I’m also still attached to the physical site of production. For example, a clearcut in the northern Rockies, or an auditorium in a military complex. These bring up conflicts: personal, economic, historical, imaginative.

KT: You know, when you think about the various “sites” involved in a production–the location or set, the editing suite, the architecture of the installation in whatever museum or gallery ends up showing the work–you like to think you have a certain degree of control. But in the end, meaning only gets made at the moment when the work is encountered by a living person. And that unique experience is ultimately beyond anyone’s control.