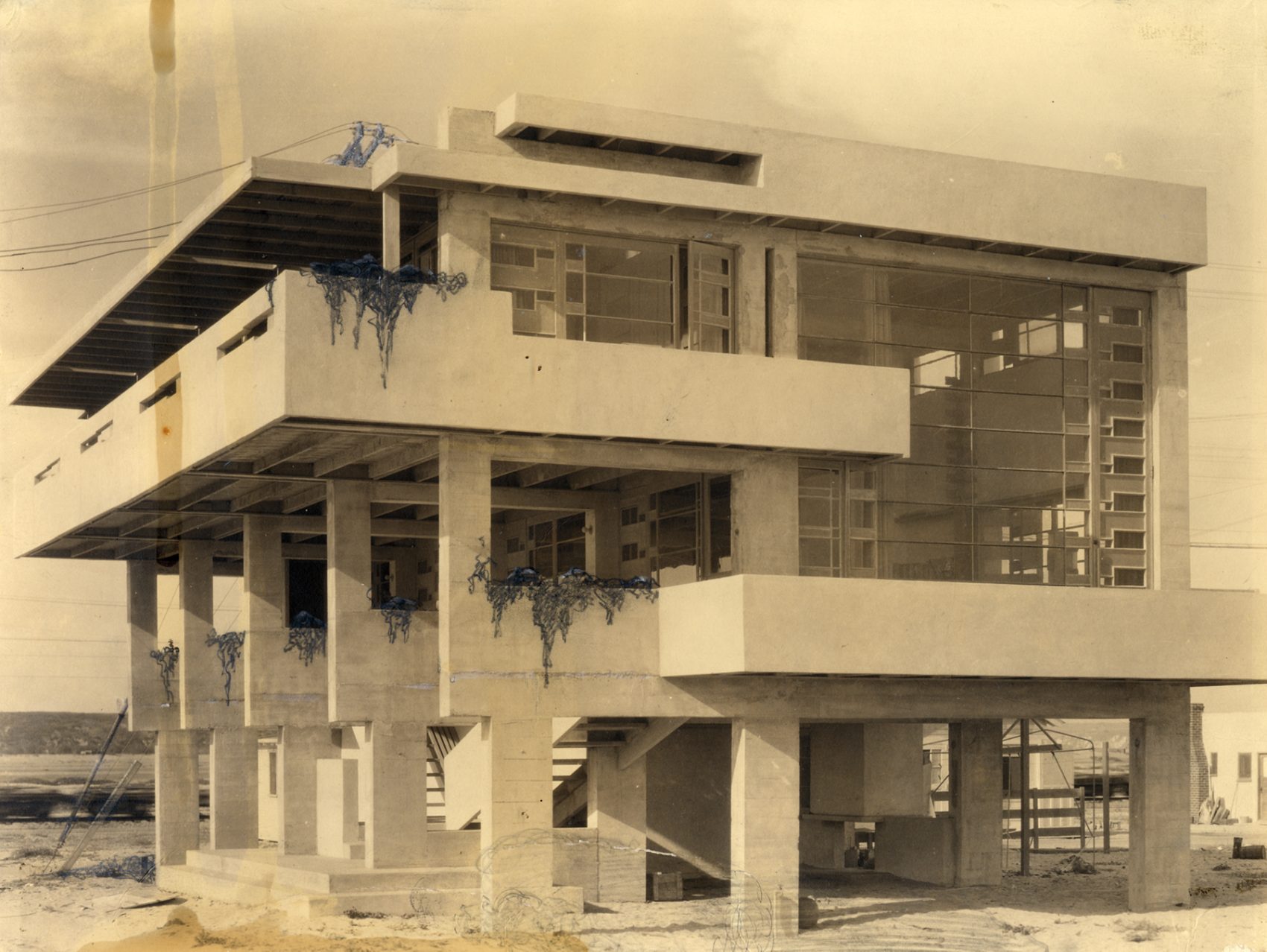

Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler’s Lovell Beach House (1926), 1927. Scan of black-and-white negative, 9 7/8 x 7 3/4 in. R. M. Schindler papers. Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC, Santa Barbara.

I first saw the Lovell Beach House in a book: Esther McCoy’s Five California Architects, one of the most “readable books of architectural history ever written,” as Reyner Banham so enthusiastically observed.1 In McCoy’s landmark publication, the Lovell Beach House (R. M. Schindler, 1926) was a standout featured in a two-page spread that included a wonderfully compelling but uncredited photograph by Edward Weston.

This seaside house, located on the Balboa Peninsula at Newport Beach, was built as a vacation home for the young family of Philip Lovell, a naturopathic physician, and Leah Press Lovell, a progressive educator and founder of “a sort of out-door nursery school.”2 In Schindler’s radical design, the living space floats above the earth, raised up by five free-standing concrete frames, a finely wrought balancing act of open air and industrial heft. When construction was nearing completion, the local newspaper dubbed it the region’s “oddest house” and sourly compared the architecture to “an inverted pyramid.”3 Weston’s photograph, however, provides an illuminating depiction of the newly built house. Looking up from the beach, the picture delivered a wide view of the house’s south elevation with its stout supports reminiscent of marine pilings, a huge patterned window, and cantilevered balconies. Considered from a slight distance, the dramatic outline of the house emerges as a Constructivist silhouette, while the raw concrete skeletal structure seems to anticipate the Brutalist architecture of the 1970s. Surrounding the house, random indicators of contemporary time and place are beautiful but slightly jarring: a Tin Lizzie-style automobile is parked next to a small board-and-batten barn, utility poles intrude across the original ranch lands, and a high-wheeled tricycle has been abandoned on the scruffy sand. Reproduced on the same page is another photograph of the house, a neatly cropped image of the southwest elevation. This is the more familiar type of illustration found in shelter magazines and architectural monographs: a portrait of the architecture as a sculptural object or engineering feat framed only by a hint of sky and the ocean’s surface visible along the low horizon. Along with these photographs, McCoy also included one of Schindler’s hand-drawn floor plans notated, in all capital letters, in his delicate Vienna Secessionist penmanship—“SLEEPING PORCHES,” a stairway “TO SUNBATH,” and “JUNIPER & VINES” along the facade.4

In 1926, while the Beach House was still under construction, Schindler had contributed six articles to “Care of the Body,” Dr. Lovell’s popular advice column in the Los Angeles Times.5 Lovell regularly evangelized about the benefits of teetotaling vegetarianism, nude sunbathing, and open-air sleeping, and Schindler wrote specifically on such topics as ventilation, lighting, and home heating. For his sixth and final contribution, “Shelter or Playground,” he emphasized the importance of fluidity in creating habitable spaces and allowing the distinctions between indoors and out-of-doors to “disappear.”6 Schindler was able to realize the Lovells’ philosophies through his own daring architectural vision for the Beach House, and the project quickly attracted public interest. As Leah Lovell told McCoy, Schindler “succeeded in incorporating every idea Philip suggested” and created a light-filled house that embodied how they wanted to live. “Schindler was like poetry,” she wrote. “Living poetry.”7

In the June 1927 issue of Popular Mechanics, there was an unsigned featurette about the Beach House, headlined “Unusual Home Is Built of Concrete and Glass,” but there was no mention of the architect’s name. Schindler’s highly modernist architecture pops out of the magazine’s Edwardian-looking pages: the accompanying photographs, attributed to Willard D. Morgan and presented in a sort of nineteenth-century carte de visite format, have been retouched into a blurry dreamscape—a watercolor swoosh erases the grubby sand, a shiplap fence has been drawn in as a backdrop, and the spare geometry of the building is emphatically traced out in dark lines and bright highlights.8 The following month, Edward Weston photographed the Beach House. As a longtime friend and patient of Dr. Lovell’s, Weston would trade photography sessions for medical advice from the “Drugless Practitioner.”9 The photographer noted in his daybook that he “responded fully to Schindler’s construction. It was an admirably planned beach home with a purity of form seldom found in contemporary houses . . .”10

In the June 1927 issue of Popular Mechanics, there was an unsigned featurette about the Beach House, headlined “Unusual Home Is Built of Concrete and Glass,” but there was no mention of the architect’s name. Schindler’s highly modernist architecture pops out of the magazine’s Edwardian-looking pages: the accompanying photographs, attributed to Willard D. Morgan and presented in a sort of nineteenth-century carte de visite format, have been retouched into a blurry dreamscape—a watercolor swoosh erases the grubby sand, a shiplap fence has been drawn in as a backdrop, and the spare geometry of the building is emphatically traced out in dark lines and bright highlights.8 The following month, Edward Weston photographed the Beach House. As a longtime friend and patient of Dr. Lovell’s, Weston would trade photography sessions for medical advice from the “Drugless Practitioner.”9 The photographer noted in his daybook that he “responded fully to Schindler’s construction. It was an admirably planned beach home with a purity of form seldom found in contemporary houses . . .”10

In 1928, when Beatrice Judd Ryan, a San Francisco-based supporter of modern art and design, expressed interest in writing about Schindler’s work for the Women’s City Club Magazine, the architect mailed her two of Weston’s photos and asked that she keep them.11 Although Judd Ryan’s proposed article didn’t materialize, the Weston photos were later published, uncredited, in the September 1929 issue of The Architectural Record. Looking at these photographs now, the modern world and untamed beachscape are evident: Weston’s images, including the one featured in Five California Architects, look straight into the twentieth century to capture startlingly new architecture, late-model roadsters, glass telephone insulators, and electrical power lines.

During the 1940s, when McCoy worked as a draftsman in Schindler’s office, she encouraged him to have his current projects professionally photographed and published. “He resisted this, or rather, asserted that his houses were too hard to photograph, and no photographer was able to do them except under his supervision,” she said, adding his claim that “the new work was more important than photography.”12 Filed among Schindler’s archived correspondence are letters so irate they could almost be comical. “Gentlemen,” he barks at the editors of Architectural Forum, “I protest emphatically against your procedure in reproducing my work against my instructions. You should know by this time that modern work can not be adequately shown by a few random photos taken by anybody whose equipment consists of nothing but a camera.”13 An unpaid invoice from Julius Shulman is marked “NONE OF THESE ACCEPTED/BILL NOT DUE.”14 Schindler informs a Mrs. Taylor: “On the whole the photographs do not convey the spirit of a modern home at all. Please give me a chance to have new pictures madam and do not use these for publication purposes.”15 Schindler’s buildings—the astonishing interiors, with their highly calibrated light sources, and the many difficult hillside sites—were, in fact, often difficult to photograph. McCoy eventually regretted her insistence that the new work be documented after witnessing Schindler heap abuse on a photographer delivering a set of prints. “Reshoot, he wrote in india ink over half of the prints,” she recalled. “Others he cropped mercilessly.”16

Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler’s Lovell Beach House (1926), 1927. Gelatin silver print with graphite and ink, 9 1/2 x 7 in. R. M. Schindler papers. Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC, Santa Barbara.

The Lovell Beach House has long been regarded as a masterwork and mentioned in the architectural pantheon of modernist domestic architecture alongside the Rietveld Schröder House (Gerrit Rietveld, 1924) and the Villa Savoye (Le Corbusier, 1929).17 In Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Banham parsed the unwieldy metropolis into quarters: he contrasted the workaday flatlands of the “Plains of the Id” with the more economically ambitious “Foothills”; the elaborate freeway system was dubbed “Autopia”; and “Surfubia” was the socially equalizing Southern California beach stretching from Malibu to the Balboa Peninsula. For Banham, the “epoch-making” Lovell Beach House indicated the southern demarcation point of Surfurbia.18 Throughout the publishing history of Beach House essays and articles, there is one Weston photograph that resurfaces, clearly a favorite among writers and book designers: a 7-by-9-inch reproduction appears in the opening pages of The Architecture of R.M. Schindler, the Museum of Contemporary Art’s splendid 2001 exhibition catalog;19 a smaller version is used to illustrate Gwendolyn Wright’s USA: Modern Architecture in History;20 and most recently, it makes a cameo in Lyra Kilston’s Sun Seekers: The Cure of California (2019).21 What’s curious about this particular image—a close-cropped view of the southwest elevation—is that it’s an especially poor work print with photo chemical spills marring the left-hand side of the picture. Looking at the original print, archived in the Architecture & Design Collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara, other curiosities visible in reproduction become even more obvious: a badly toned photo, unsuitable for publication, has been altered by hand, most likely Schindler’s. Glistening pencil marks, slack lines draped midair, run up to the roof: extra wires, presumably leading to unseen poles, link this modern house to the modern world of telephones and municipal utilities. Power lines and telephone wires rarely show up in architectural photographs, but in the 1920s, when Weston and his contemporaries Alexander Rodchenko and Tina Modotti were producing images of skies inscribed with industrial tracery, their photographs conveyed a different message, with photographs celebrating a brave new world.22 The print has also been altered with inky additions: dark clumps of scribbled vines hang down from the balconies and sleeping porches. At the base of the concrete frames, a lightly penciled swirl suggests tumbleweed or the sprawling juniper shrub indicated in Schindler’s floor plan.23 A version of Weston’s photo of the southwest elevation—the second image featured in McCoy’s book—had appeared earlier in Sheldon Cheney’s The New World Architecture (1930). Although the overall image is exactly the same, pencil-drawn landscaping has been added to the 1930 edition: spindly vines with ivy-like leaves twist upward around the concrete frame and spill off the balconies. A pointy shrub, like the spiky vegetation bordering Schindler’s floor plan, has been penciled in at the corner.24 If Schindler drew on these prints, he knew what he wanted to see even when nobody else was looking.

Over the years, the Lovell Beach House has entered into architectural history, and the world has been deluged with images; photographs of absolutely everything have become ubiquitous.25 As a historic house and a vintage photograph calcify into accepted ideas, taking notice tends to slip away. Philip Yenawine, former education director at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and cofounder of Visual Thinking Strategies, has written about how children initially learn by looking and figuring things out, but that skill, an inherent visual curiosity, tends to fade when eclipsed by language. In outlining how to rekindle visual thinking, Yenawine poses questions for the viewer. “Can you show us what you’re seeing?” he asks. “Can you add more words to help us understand?”26 I take those words to heart and keep looking.

Susan Morgan’s writing about art, design, and cultural biography has been featured in specialist periodicals and mainstream magazines—publications as diverse as Aperture and W. Her research about American modernism has been supported by the Center for Creative Photography, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center, and the Graham Foundation.