The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America, Installation at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2006. Photo: Joshua White. Courtesy of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Walking through the Hammer Museum’s recent Société Anonyme exhibition, I was struck by the collection’s broad scope. The subtitle of the exhibition, “Modernism for America,” refers to the original goal of the Société’s artist-founders, Katherine Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray. They aimed explicitly to educate the American public about contemporary art through exhibitions and related programs beginning in 1920. What is elided by the subtitle is the fact that their vision of Modernism seems to be very different from what is generally understood by the term in North America today. Already in about 1940, Chilean artist Robert Matta Echaurren called the collection “one of the most important” precisely because it contained not only works by well-known artists but also good examples of works by “little known star artist [sic] of Germany France…and America.”1 Curator Jennifer Gross shows that this role of the Société was deliberate and important to Dreier.2

Gross suggests a couple of reasons why so many of the artists presented here have not made it into the survey text or even into the popular memory of Modernism as constructed by American museums. “Many of these artists have been lost to art history,” she surmises, “whether because of the peripatetic lifestyle that many of them shared during the economically and politically tumultuous period of 1920-40 or, in some cases, because of early deaths due to illness, persecution, or military service.”3 I don’t think these individual fates can account for the amnesia this show suggests. Franz Marc died early on the battlefields of the First World War, but his work and reputation have been preserved, championed and researched thanks to collections and lasting institutions in Germany and the United States—in the Lenbachhaus in Munich and the Norton Simon in Pasadena, to name only a few. László Moholy-Nagy served and was wounded in the First World War. His trajectory is representative of many of the Hungarian artists who participated in the MA (Today) group in Budapest and in exile in Vienna after the overthrow of the brief Hungarian Soviet regime in 1919.4 Moholy-Nagy moved from Szeged to Budapest within Hungary, and on to Vienna and then Berlin, Paris, and Amsterdam, before being invited to Chicago to head the New Bauhaus. This exiled outpost of experimental education developed into the Institute of Design, one of the most important schools of photography in twentieth-century America.5 Moholy-Nagy was clearly a peripatetic artist, but his institutional affiliations preserved his work and legacy. I would offer a less romantic image of the effect of interwar tumult and exile, war and politics. Many of the artists in this exhibition have been forgotten due to a lack of something as mundane as institutional memory. An artist is not wholly defined or remembered by institutions, but nor should the loss to art history of so many of the artists in this exhibition be cast as random or even wholly accidental.

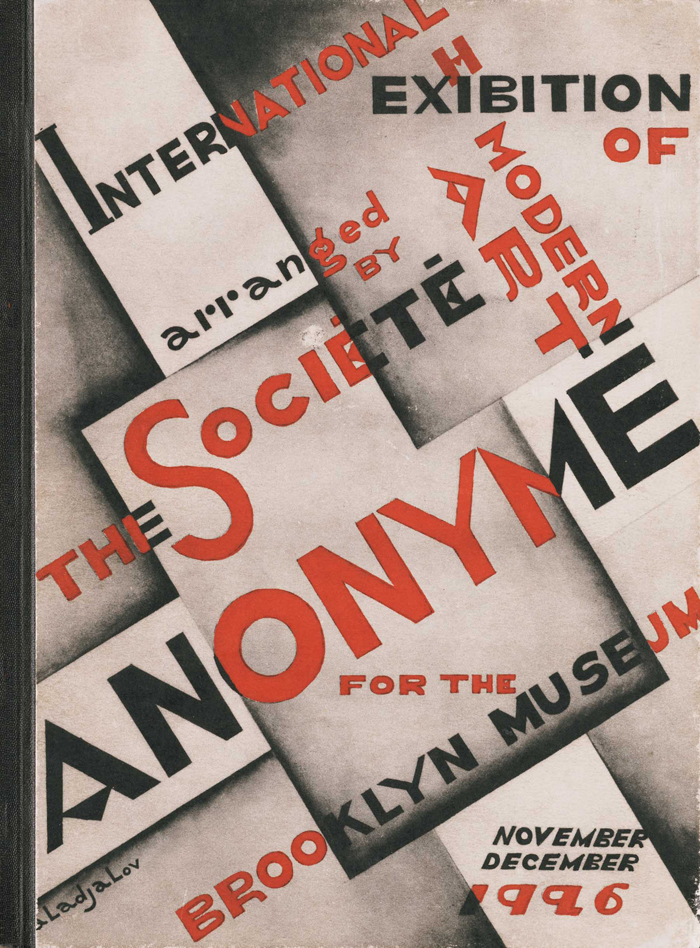

Constantin Alajálov and Katherine S. Dreier. Cover of Modern Art, 1926. Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Société Anonyme Archive. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

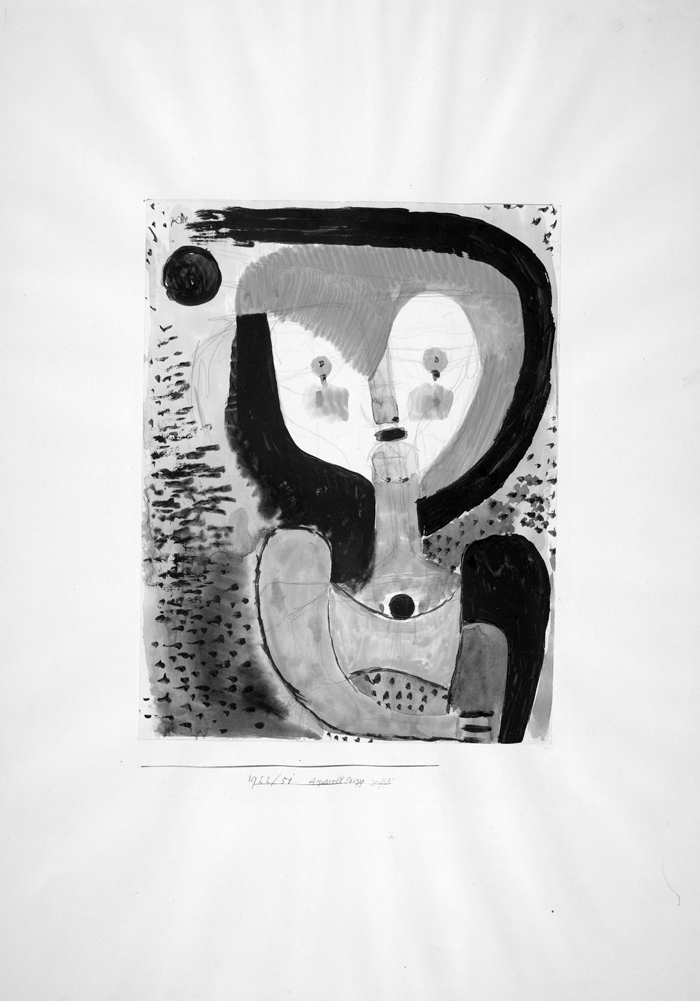

Our current understanding of Modernism, developed by a variety of scholars over the last five decades, is heavily imprinted by the Cold-War view of Europe as a space divided into West and East. This exhibition goes a long way towards demonstrating the artificial and misleading nature of the gulf we now perceive between the modern cultural contributions of Eastern and Western Europe. The exhibition presents side by side the ideas of well-known artists who are not generally discussed together, such that we see Paul Klee and Moholy-Nagy as engaged in a conversation, rather than consumed by separate, introverted self-examinations. Klee’s 1922 watercolor sketch for the cover of the Hungarian journal MA (then published in Vienna) depicts a schematized figure in bright orange and green whose whimsical expression contrasts with the almost geometric solids of hair or hat, arms and clothing that frame it. Klee’s contribution to the exiled Hungarian artists’ journal is a concrete reminder that the relationship between East and West was not unidirectional. This is not only a story of rehabilitating forgotten artists and lost works of obscure origins (to the West). Western artists engaged with a far broader spectrum of journals, dealers, galleries, and exhibitions than the canonical art historical narrative of Modern Art acknowledges.

Beyond preserving surprising reminders of the interconnectedness of well-known moderns, the Société Anonyme exhibition includes along with them, taking part in the discussion, the understudied works of such artists as Louis Marcoussis, László Péri and David Kakabadzé. Péri’s Room (Space Construction) (1920-21) uses a constructivist strategy of contradictory signs for (and against) flatness and dimensionality. He contradicts the flattening effect of repeated bright orange, green and black geometric shapes by interrupting the left side of the painting with a perspectival receding diagonal edge. The shaped canvas works to create space on the left, but seems arbitrary on the right. An undecipherable yet seemingly three-dimensional shape looms incomprehensibly in the painting’s lower right half, denying the viewer a simple identification of the “room” in the work’s title.

László Peri, Room (Space Construction) (Zimmer), 1920–21. Tempera on composition board, 39 x 30 in. Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of Collection Société Anonyme.

Marcoussis’s remarkable Fish (1926) also plays with flattening geometry and enlivening diagonals. Pierre Legrain’s angled wooden frame confronts the cubist vocabulary of the painted island of a still-life with actual wood grain, and contradicts the flatness of painting in general with the aggressive three dimensions of sharp angled prisms that recede and jut behind and around the dwarfed painted surface. This work embodies the Société’s idea of dialogue: between three dimensions and two, painting and sculpture, figure and ground, illusion and reality, Polish painter and French frame-maker. Kakabadzé’s almost comical Z (The Speared Fish) (c. 1925) seems to continue the conversation in a large, painted wood, metal and glass free-standing sculpture.

Péri, Marcoussis and Kakabadzé confound categories by crossing from one medium to another but also by clearly responding to and transforming Moholy-Nagy’s or Malevich’s constructivisms, Braque’s later cubism, or Brancusi’s organic abstractions. They also challenge the curators’ task of identifying artists by nationality. Many of these designations, required by art historical convention, create more confusion than clarity. A few representative examples can demonstrate: Alexander Archipenko is listed as “Russian, lived France and United States,” while David Burliuk is listed as “American, born Ukraine.” Archipenko was born in Kiev in 1887, and Burliuk was born in Kharkov in 1882. Both cities were then part of the Russian Empire, but are now within the boundaries of contemporary Ukraine. I would be curious to know what criteria were used to determine the identification of many of these artists as American. Louis Lozowick is listed as “American, born Russia,” though the first line of his short biography in the catalogue begins “Born in Ludvinovka, Ukraine, in 1892…” These are minor quibbles of consistency, but they indicate a larger issue. Many of the Eastern European artists discussed here hail from areas that have undergone numerous changes in government and national boundaries over the last century. The seemingly straightforward task of indicating their national origins already problematizes the notion that Modern Art history is a narrative of progressive competition between clearly defined national cultures.6

Paul Klee, Watercolor Sketch for “MA” (Aquarelleskizze zu “MA”), 1922. Pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, 11 5/16 x 8 5/8 in. Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of Collection Société Anonyme © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

In a review of Steven Mansbach’s Modern Art in Eastern Europe: From the Baltic to the Balkans, the only general study of Modern Art in Central and Eastern Europe written in English, James Elkins reflects that such a book, focusing on works outside the accepted canon, raises several important questions about Modernism in general: “What is the global nature of Modernism? What should be counted as the essential moments of Modernism, East or West? What can be ignored, and why? What is regional art, as opposed to art of the center? What was avant-garde at any given moment, and what else beside it counted?”7 He follows this list of questions with the statement: “ I cannot think of more important questions when the subject is twentieth-century painting: they are essential for any firm understanding of the shape of the century.”8

In any discussion of avant-garde art of the early twentieth century, one of the more complex notions to illustrate is the impact and embrace of the international. Many artists professed a utopian search for a visual language that could transcend national boundaries. One of the artists Dreier most admired, Wassily Kandinsky, was an energetic proponent of leading the rest of society toward the kind of universal enlightenment he sought in the language of abstraction. His work was the focus of one of the first solo exhibitions mounted by the Société. But Kandinsky’s goals are as abstract as his paintings and they remained theoretical. What is striking about this exhibition is the concrete evidence it provides of the fertile cross-pollinations and mutual interests of Modern artists from an enormous variety of artistic centers.

Naomi Hume is Assistant Professor of Modern Art History at Seattle University.