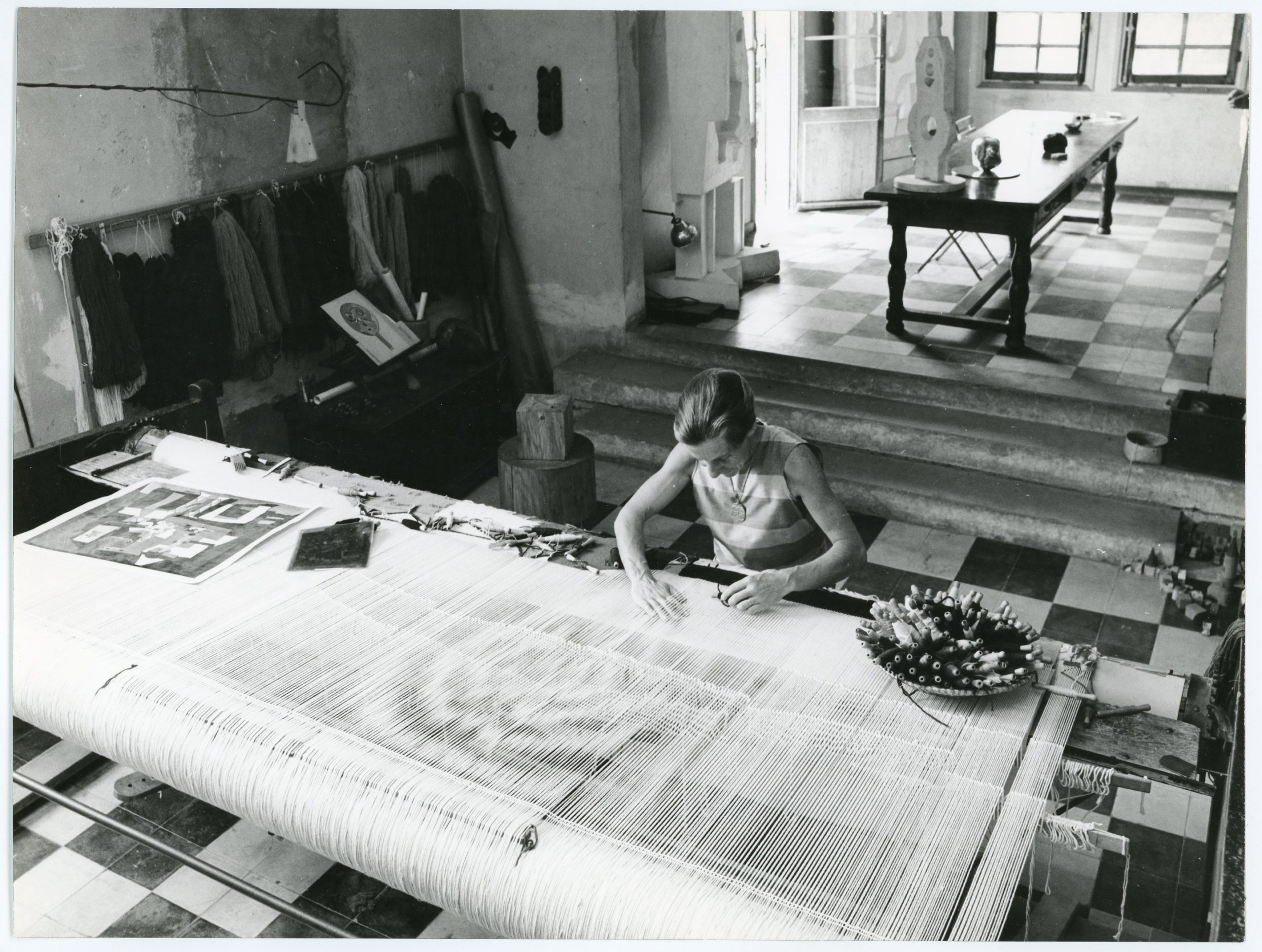

Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach, Guernica tapestry, 1973. Archives de Marseille, 82 Fi. Photo: Marcel Coen.

In February 2021, a tapestry inspired by Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which the artist made in response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Gernika in 1937, was removed from the entryway of the United Nations Security Council in New York City.1 The artwork was created by Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach in the Var region of Southern France in 1955 and purchased by Nelson A. Rockefeller that same year. Picasso had refused to sell his original painting to the Rockefeller family, instead instructing that the work be gifted to the National Museum after Spain’s liberation from Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. With Guernica unavailable, Rockefeller decided instead to purchase Dürrbach’s Guernica, which was meticulously woven with eleven colors of wool yarn across nearly one-thousand skeins of cotton warp.

In 1959, the Guernica tapestry followed Nelson Rockefeller to the governor’s mansion in Albany, New York. It later traveled to exhibitions throughout the United States and Japan, and was lent to the UN Headquarters in 1985, where it stayed until 2009. While the UN Headquarters was undergoing renovation, the tapestry traveled to London and San Antonio, returning to the UN in 2015.2 To date, no official reason has been given for the termination of the tapestry loan in February 2021.3

I am interested in unraveling the public life of Dürrbach’s Guernica for myriad reasons. Leaning on Jorge Luis Borges’s fable about a map that was so precise as to cover the land that it was tasked with mapping, I want to ask whether the Guernica tapestry operates as a stand-in for the original—indeed, as a surrogate for the painting that it is tasked with representing. Unlike Picasso’s Guernica, which due to the fragility of the stretcher bars may no longer leave Madrid, Dürrbach’s Guernica, which is woven at a size that nearly matches the scale of Picasso’s painting, can be rolled up, packed, and sent around the world.4

Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach and Pablo Picasso in Mougins, France, 1967. Archives de Marseille, 82 Fi. Photo: Marcel Coen.

For the Guernica tapestry and all subsequent tapestries commissioned by the Rockefeller family, permission was granted to weave three identical versions—the first for the Rockefeller collection, the second for Picasso, and the third remaining at Dürrbach’s manufactory, Atelier Cavalaire.5 The verified reproducibility of Dürrbach’s handiwork coupled with the painstaking mechanization of fine, low-warp point (each tapestry took six months to produce) contrasts with the material conditions of Picasso’s frenetic markings of monochromatic housepaint on machine-woven canvas over the course of thirty-five days.6

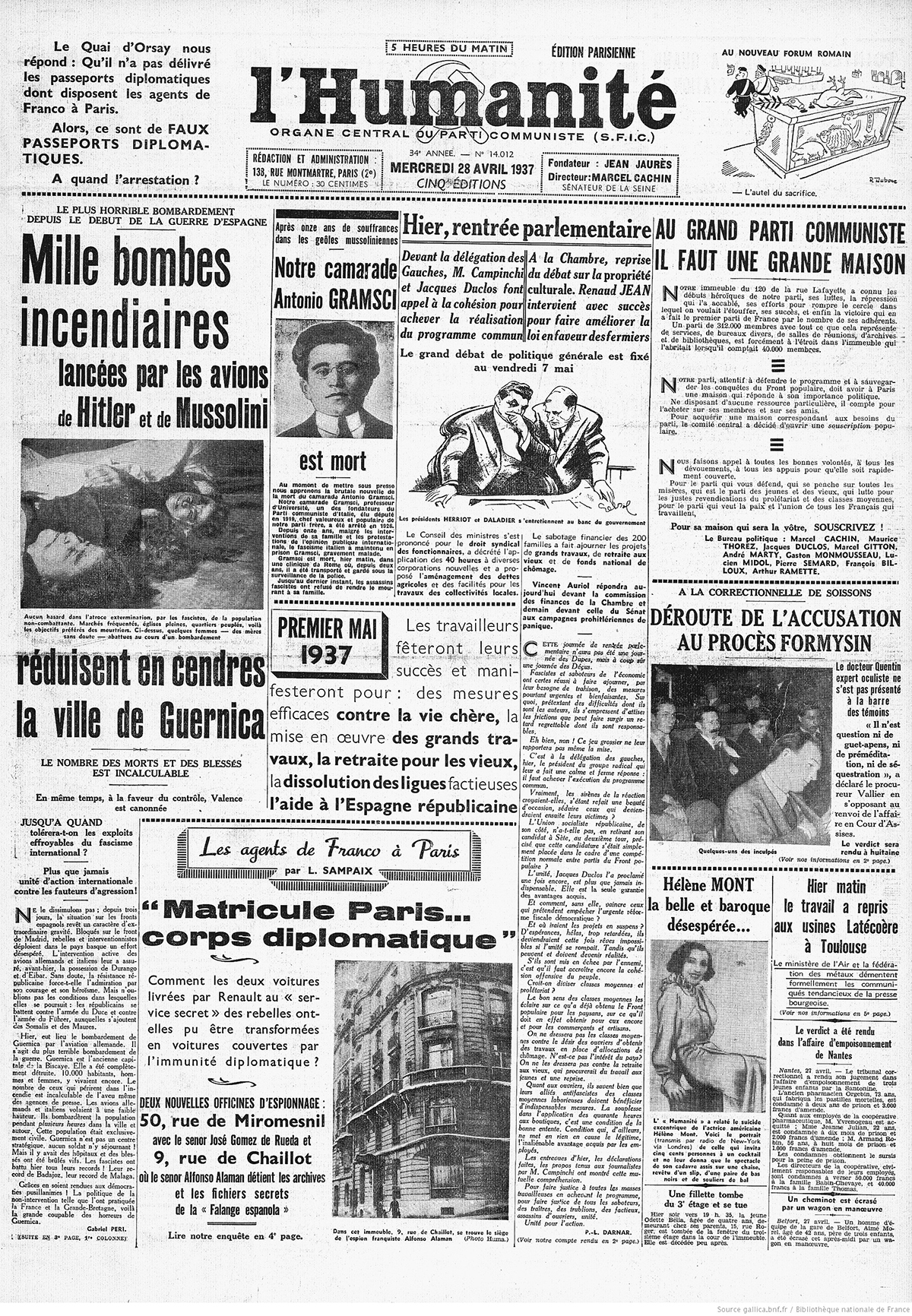

When Picasso’s Guernica debuted in Paris in July of 1937, mere weeks after it had been completed, paint and wounds were still fresh. Not yet history painting, Guernica performed the role of the daily news, bearing witness and responding to civil conflict in the present tense.7 In contrast, when Dürrbach began her first Guernica tapestry in April of 1955, although the Spanish Civil War would not end for another two decades, Guernica would largely be perceived as allegory—no longer the marker of a precise node within the larger fascist project but rather a testament to the violence and death wrought by any military occupation.8 Picasso’s Guernica was painted in colors and striations that mirror the black-and-white Ben-Day dot photographic reproductions printed in the French Communist newspaper L’Humanité—vistas of the aftermath that comprised the artist’s most authentic encounter with the massacre. But Dürrbach wove her Guernica in browns, taupe, and sepia, colors that recall an aging broadsheet bearing yesterday’s news. Viewers of the Guernica tapestry are invited to imagine a time before the formation of the United Nations, when the West was in a state of profound disorder—a clever mythology that permits both the UN coalition and the Rockefeller family, self-proclaimed peacekeepers, to frame evidence of military violence as a historical fact while rebuffing their own culpability to contemporaneous manifestations of this very violence.

Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach weaving Picasso’s Three Musicians, Cavalaire-sur-Mer, France, c. 1966. Archives de Marseille, 84 Fi. Photo: Marcel Coen, © Succession Picasso, 2022.

A letter sent to the Museum of Modern Art’s Board of Trustees on November 10, 1969, confronted the Rockefeller Foundation’s culpability head-on, drawing a straight line from David and Nelson Rockefeller and their corporate trust, Standard Oil (of which the Rockefellers held majority ownership), to arms manufacturers and chemical warfare, most strikingly their contribution to the development of napalm.9 After the Rockefellers refused to comply with the letter’s insistence that they step down from the MoMA Board, the signatories—members of the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC) and the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG)—staged a now-famous protest. Holding posters bearing a graphic depiction from the My Lai massacre, Tom Lloyd, Jean Toche, Joyce Kozloff, and others demonstrated in front of Picasso’s Guernica at MoMA, calling on the Board of Trustees to revoke the Rockefellers’ membership and calling on Picasso to withhold Guernica from public view until the conclusion of the Vietnam War. Picasso ultimately rejected their demands.10

The Art Workers’ Coalition’s appropriation of Ron Haeberle’s 1968 color photograph of countless slain Vietnamese civilians, pulled from Life magazine and emblazoned with blood-red type that reads “Q: And babies? A: And babies” is of particular interest.11 Unlike the massacre on Gernika, a blitzkrieg that Picasso was compelled to imagine rather than witness due to a dearth of embedded photojournalists, the entirety of the Vietnam War appeared to have unfolded in front of Nikon cameras eager to capture its most devastating consequences. Guernica could stand in for any war precisely because the people and animals depicted are fixed neither in time nor place. Rather than being grounded on the land that constitutes the theater of war, stylized depictions of women, children, and animals drift, flail, and agonize on a deep grey void. Haeberle’s graphic depiction of My Lai, on the other hand, indexes specific women, children, and indeed, babies in a specific landscape, largely evading allegorical framing.12

On February 28, 1974, AWC member Tony Shafrazi spray-painted “KILL LIES ALL” on Guernica at MoMA to protest Nixon’s pardoning of Lieutenant William Calley Jr., who commanded the My Lai ambush and was the only participant to be convicted of a crime. The impulse to obfuscate and thus clarify Guernica with instantiations of present-day conflict, evidenced in performative actions by members of the AWC, attests to the painting’s lasting transmutability. To these art workers, Guernica is a palimpsest onto which the citizenry is obliged to contribute periodic updates and revisions. And although it may be true that security at the Reina Sofía has taken extraordinary measures to ensure that future accretions never reach the surface of the antiwar allegory par excellence, the invitation for appraisal nonetheless remains permanently open.

Members of the Art Workers Coalition in front of Picasso’s Guernica at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, January 3, 1970. Photo: Jan Van Raay.

One such appraisal, or should I say redaction, embellished the Guernica tapestry at the UN Security Council on February 5, 2003. On this day, a blue curtain was hung in front of Guernica, covering it entirely from view, on the occasion of US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to UN member states.13 No official reason was given for the cover-up, although New York Newsday reported that, “Diplomats at the United Nations, speaking on condition they not be named, have been quoted in recent days telling journalists that they believe the United States leaned on UN officials to cover the tapestry, rather than have it in the background while Powell and other US diplomats argued for the war on Iraq.”14 Conservative news source Washington Times reported, “Television cameras routinely pan the tapestry as diplomats enter and leave the council chambers, and its muted browns and taupes lend a poignant backdrop to the talking heads. So it was a surprise for many of the envoys to arrive at the U.N. headquarters last Monday for a Security Council briefing by chief weapons inspectors, only to find the searing work covered with a baby-blue banner and the U.N. logo.”15

Powell, the first Black Secretary of State, born in Harlem to Jamaican immigrants and raised in the Bronx, a four-star general who had no truck with the global oil market or private-sector defense contracting, was handpicked by President George W. Bush to deliver a speech that was engineered in the office of Vice President Dick Cheney. As if to deflect impending doubt, Powell affirmed, “My colleagues, every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are not assertions. What we are giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.”16 As Powell proceeded to spin a tale replete with CAD-rendered semitrucks hiding depleted uranium and a small glass vial filled with anthrax, a message that the American news was more than willing to embrace wholesale, anti-war activists demonstrated outside the United Nations brandishing photo reproductions of Guernica.17

In warning the international community about acts of terror that had not yet been fulfilled and would never come to be, at least not in the way that Bush and Cheney had promised, I want to argue that Powell’s approach to brokering lies to the American public owes its success in part to the media campaign that followed the bombing of Gernika. Whether to wash the blood from their hands or to provoke bewilderment, state-sponsored news in Germany and Spain placed the blame for the Gernika massacre squarely on the Basque Communist Party—a propaganda technique that gained traction after a similar strategy was used effectively following the Berlin Reichstag Fire of 1933. In London, columnists for the conservative Times doubted the firsthand testimony of their own correspondent, George Steer. Steer’s breaking news report, which was published in the London Times and New York Times on April 27, 1937, described the ammunition rounds that ripped indiscriminately through the bodies of villagers and livestock. Picasso first read Steer’s report in L’Humanité two days later, and it inspired the painting that would come to symbolize the entirety of this tragedy.

Colin Powell addresses UN member states, February 5, 2003. Photo: Executive Office of the President of the United States. Public domain.

Instead of striking first and denying later, the Bush Administration struck after scattering the seeds of justification. Provoked by the events of September 11, 2001, George W. Bush’s presidency represented the last time that the corporate media apparatus would stand in lockstep behind the words and wishes of an American president. In the forty-three days between Powell’s presentation at the United Nations and the US military’s first strike on Baghdad without declaration of war, MSNBC, a left-leaning cable network owned by military defense contractor General Electric, summarily fired Phil Donahue, their only correspondent to openly interrogate the invasion of Iraq. If one opened a newspaper or turned on the news in early 2003, one would be led to believe that every American heeded Colin Powell’s austere warning. One would need to go out into the streets of college towns and American cities to find evidence of resistance. Not coincidentally, many of these protestors also held signs bearing the likeness of the Gernika ambush that was redacted from Powell’s presentation.

“Twenty-four-hour news networks are built for one thing, and that’s 9/11. There are very few events that would justify being covered 24 hours a day, seven days a week. So in the absence of urgency, they have to create it. You create urgency through conflict.”18 These words from Jon Stewart are instructive to better understand the colonization of real time prompted by the twenty-four-hour news cycle, particularly in the months and years leading up to Web 2.0. After September 11, George W. Bush told Americans that their civic duty was no longer to conserve, to volunteer, or to enlist, but to shop. Exempt from engaging in now-antiquated modes of patriotic exercise, many turned on their televisions.

Front page of L’Humanité, April 28, 1937.

Less than two hours after the attacks on the World Trade Center, Fox News became the first network to run a news ticker at the bottom of their screen 24/7—an on-screen graphic that is both mirrored and materialized with a red-on-black LED ribbon that circumscribes the façade of their corporate headquarters at the Rockefeller Center, one mile west of the UN Headquarters. The ticker’s resemblance to the endless linear glide of the stock market marquee made the objectives of the news media crystal clear. Consumers no longer needed to pull the wool back from their eyes or wear special glasses, like the ones featured in John Carpenter’s film They Live, to learn that civic awareness and market capitalism are cut from the same machine-woven cloth.

At the turn of this century, the speed at which the separation between work and leisure dissolved for middle-class Americans was matched only by the speed at which the separation between news and entertainment became increasingly blurred on their television screens. Titles, graphics, split-screens, and screens within screens conditioned viewers to receive multiple layers of information simultaneously—a skill that would be vital to consuming the news on smartphones in the latter half of the decade. Like Dürrbach’s tapestry, which became a surrogate for Picasso’s painting—a didactic stand-in that would fulfill the role of the diplomat, travelling from place to place to attest to the barbaric consequences of war—the twenty-four-hour news cycle became a surrogate for time itself. Suddenly, one’s entire worldview could be constructed from information gleaned from a single unremitting frequency.

But what could such a frequency tell us about the world? In advance of the Gulf War, President George H. W. Bush ordered a press ban on images of flag-draped coffins—a moratorium that would not be lifted until after Bush’s son left office nearly two decades later. On CNN, Operation Desert Storm was showcased as a five-week spectacle of targeted bombings—dust-clouds and murky green explosions that appeared to spare both Iraq soldiers and Kuwaiti civilians from their worst consequences.19 Five weeks into his own war on Iraq, George W. Bush famously addressed soldiers in front of a banner reading “Mission Accomplished.” Between his speech in May of 2003 and the leak of photographs of the torture of Abu Ghraib prisoners one year later, images of suffering were relatively difficult to come by. War became tolerable.

Screenshot from Fox News coverage, September 11, 2001.

Although images of suffering will eventually cause most viewers to turn away, as Susan Sontag observed in Regarding the Pain of Others, the histories examined above make clear that, when consumed in modest doses, these images routinely compel leaders to think twice about perpetrating war, while compelling the masses to think twice about supporting them. Correspondingly, the absence of such imagery nurtures complacency. So why remove Guernica from the UN Headquarters now? Because the Rockefeller family has offered no reason for the termination of their loan, I can only speculate.

Guernica was removed from the walls of the UN Security Council as President Joe Biden was ending America’s longest conflict. If the war in Afghanistan reaffirmed anything for global leaders, it is that violence is better inflicted in the shadows—through sanctions, surveillance, contras, coups, drone strikes, arms sales, IMF-imposed debt, and indirect control over the corporate media apparatus. The vice-grip of neoliberalism on markets, democracies, and global news is telling. Instead of striking first and denying later, as the Luftwaffe did in Gernika, or sowing the seeds of justification before striking, as Bush did in Iraq, today, the rationale, labor, and profit of violence is habitually cloaked in darkness and outsourced to third parties. When evidence of state-sanctioned violence is leaked to the media—which is increasingly rare in a legal environment where whistleblowers are prosecuted brazenly—the dossier surfaces in a specter of confusion and disbelief, quickly gliding past a press corps that is perpetually fixated on the new.

Nowhere can the by-product of state-sanctioned violence be seen in starker relief than at the so-called Calais Jungle. One outcome of the European Migrant Crisis of 2015, the Calais Jungle is the largest relocation of people across the continent since 1945.20 Here, several thousand asylum seekers from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, among other war-torn regions, took residence at a vacant landfill while awaiting refugee status (which for most never arrived) or an opportunity to flee into the United Kingdom.

In the international press, the one and a half square mile encampment was routinely photographed from above, revealing an expanse of blue UN-issued tarps. Like the curtain that shielded UN members from the brutality of the Gernika blitzkrieg in advance of Powell’s appeal to war, the blue-washing of Calais shielded Westerners from viewing the bodies of those most impacted by the violence that had forced them West to begin with. Bearing neither an explanation for nor a solution to the watershed crisis that the Global North had exacerbated, the UN leaned on its humanitarian division to offer relief to its most conspicuous victims. With little doubt, the liberal elite’s failure to address the crisis of migration has left an opening for right wing nationalism to capitalize on fear. The Calais migrant camp was demolished on October 24, 2016, two weeks before Donald Trump’s presidential victory.

Like a photograph of diseased lungs printed on a pack of cigarettes, the Guernica tapestry served as a deterrent, stirring world leaders to reconsider the consequences of war. Now that Guernica no longer greets UN members at the door, visitors are free to project new stories onto this vacant wall—including but not limited to narratives that cast doubt on historical acts of violence while opening a door for contemporaneous strains of violence to fester. To the extent that this outcome is objectionable to UN gatekeepers, and to the extent that they have the authority to change course, the sensible action would be to shroud the tabula rasa with a new work of art. Were this decision to be made by a confederation of global citizens rather than by an oil baron and UN personnel, one outcome might be the arrival of an artwork that reflects on common empowerment rather than historical atrocity. For, while images of violence have long served to forewarn against the proliferation of further violence, it is well known that these very images can be used just as fervently to garner support for retaliation. If, in fact, the UN General Assembly is committed to ending cyclical violence in all forms, both between rival nations and between rival factions within common territories, the need to replace Guernica with an artwork that speaks not only to victimization but to social justice is doubly urgent.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt weighs the inclusionary principles of state-building and its commitment to providing liberty for a plurality within the modern nation-state against the exclusionary principles of nation-building and its commitment to erasing difference in search of a unified polity.21 Because the warp of the state and the weft of the nation can only coexist while held in a kind of “para-logical suspension,” a phrase coined by Rosalind Krauss in her essay “Grids,” it stands to reason that the UN should strive to nurture a system of checks and balances within which a thriving coalition of nation-states can also coexist.22 However, since the conclusion of the Cold War, UN-advised tribunals have used their authority to convict the ruling parties of just four nations (Cambodia, Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Iraq), while not once opening investigations into the military conquests or domestic clampdowns of any UN member with veto power (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, or the United States).23 And so it would appear that the rights of any given citizen under the UN Charter are wholly reliant on the citizenship in question.

Guernica tapestry being rehung outside the United Nations Security Council Chamber, February 5, 2022. Courtesy of UN Photo. Photo: Mark Garten.

Cast in this light, the Rockefeller family’s decision to remove Guernica from the UN might be interpreted as a concession to Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, penned in 1992 as the last vestiges of European totalitarianism were swept off the path of liberal democracy.24 In this scenario, the vacant wall adjoining the entry-point to the Security Council would be reimagined as a twentieth-century avant-garde monochrome painting—albeit, true to Kazimir Malevich’s prophesy, a monochrome that has been fabricated and is maintained by union workers, whose camaraderie aligns with proletariat autonomy above bourgeois hegemony.25 Here, rather than being confronted with the abject horror of the Guernica tapestry, the UN diplomat is invited to draw a blank—indeed, to gaze into a deep void onto which the political imaginaries of the last century can no longer stake claim. In keeping with Clement Greenberg’s proclamations on American abstraction in the early years of UN formation, this diplomat, newly liberated from the baggage of figure-and-ground relations, would no longer be inclined to brush up against historical allegory but instead would be invited to contemplate the corporality of the perceivable—latex housepaint applied with rollers onto drywall.

But alas, I can no more advocate for this neoliberal farce than can Fukuyama, who, after witnessing profuse evidence of geopolitical violence following the dissolution of the USSR, has backpedaled his swan song to modern history. Would it not be more realistic to imagine a scenario in which the global precariat stormed the historical properties of the Rockefeller family—as the Parisian peasantry stormed the Louvre in the throes of the Second Revolution—including the Museum of Modern Art, where the people of New York have never been granted a seat at the board’s table; the Rockefeller Center, where one would no longer be obliged to consume the feckless punditry of Fox News and MSNBC in stereo; and, most importantly, the UN Headquarters, where the insurgents would at long last be in a position to replace Guernica with an artwork nominated through consensus?26

One can only dream. In the meantime, I will turn to art historian James Aulich, who insisted that the Art Workers’ Coalition’s Guernica protest was effective only insofar as it was instantiated against the wishes of the museum—and moreover, that images of war have far greater potency when brought into the streets than they ever will on the walls of MoMA (or the UN, for that matter).27 If this much is true, it is incumbent on those who oppose premeditated acts of violence wielded by global elites to uphold Guernica as an object of sustained protest, lest the horrors depicted therein are coopted by the elites once more or, worse yet, forgotten entirely.

Postscript: Since completing the final draft of this essay in early 2022, a series of developments have surfaced in the news. On January 31, 2022, US Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield met with Russian Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia at the UN Security Council to discuss the prospect of armed conflict in Ukraine, the prospective horrors of which could hardly be fathomed with Guernica in absentia. Six days later, the Guernica tapestry was unexpectedly returned to the UN Headquarters. In a telephone interview with the New York Times, Nelson A. Rockefeller Jr. stated that there had been a miscommunication: Guernica was simply being cleaned, and his intention had always been to return it to the Security Council.28 In a video posted on the United Nations website, art workers clad in black uniforms and white gloves affix the Velcro-backed tapestry to the barren wall it had been torn from, one year earlier. Next, the art workers pose in front of Guernica as an onlooker commemorates the occasion by capturing their likenesses on their iPhones. The video ends with a photomontage of shaky tracking shots showcasing the freshly laundered tapestry set to the indiscreet hum of an industrial vacuum cleaner.29

I will not attempt to predict where the ensuing conversations between American and Russian diplomats will lead, not least because by the time this essay is published, the reader will undoubtedly have a better perspective. Instead, I will speak from the ground. The drumroll of impending war sounds all too familiar. Indeed, in a heated exchange, Ambassador Nebenzia said to Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield, “You are almost calling for this, you want it to happen . . . as if you want to make your words become reality.”30 In addition to evoking the career of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who played the President of Ukraine in a popular television show before being elected the President of Ukraine, Nebenzia’s words, albeit conniving, reveal profound truth regarding the deftness with which American policy makers and the corporate media collaborate in constructing the ends that justify their means.31 One year after ending the War in Afghanistan, the United States will spend a record $770 billion on military defense, $24 billion more than Biden requested from a Congress that cannot agree to allocate taxpayer dollars to much else.

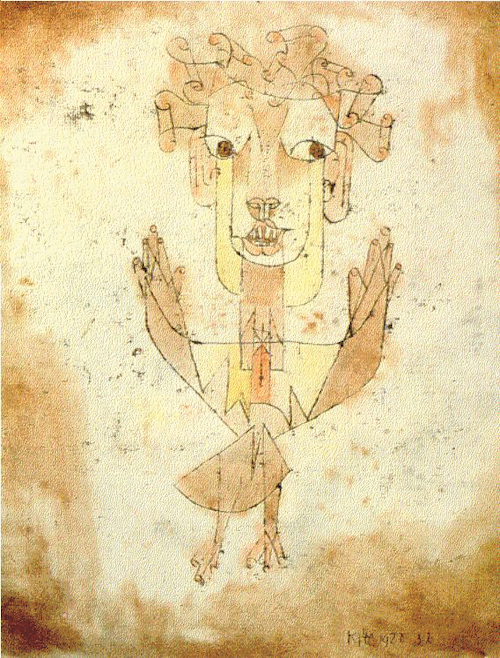

And so, when US and Russian diplomats return to the UN, will they pause in front of Guernica and thus be reminded of their once-shared commitment to defeating European fascism? And will this fleeting moment of comity deter them from utilizing the war materials that bolster their national economies? I have little choice. I must leave space for Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) to illuminate my conjectures.32

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus , 1920. Oil transfer and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Israel Museum.

David Weldzius is an artist based in Los Angeles.