Tamar Guimarães and Kaspar Akhøj’s film Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter (2017) ends with a close-up of an insect grooming itself on an infamous plant, Caesalpinia pulcherrima. German entomologist and scientific illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian delicately painted this same plant in her 1705 book Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam. Of this plant, commonly known as the peacock flower, Merian notes:

The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds to abort their children, so that their children will not become slaves like they are. The black slaves from Guinea and Angola have demanded to be well treated, threatening to refuse to have children. Indeed they even kill themselves on account of the usual harsh treatment meted out to them; for they consider that they will be born again with their friends in a free state in their own country, they told me this themselves.1

In the film, we see a man beheaded by shadow sitting beneath this plant. The image is repeated twice, at the beginning and in the middle, with two different men sitting in this dappled light and fragmented by the camera frame. Both subjects live in Palmelo, Brazil, the last country in the Western world to abolish slavery, in 1888. I learned about Palmelo from Captain Gervasio’s Family (2013/2014), an earlier film by Guimarães and Akhøj. Palmelo was founded in 1929 by a man named Captain Gervasio. A group of eighteen people, including Gervasio’s descendants, created a Spiritist study group, Luz da Verdade, that later became a Spiritist center with an accompanying sanatorium that healed its patients through energy work known as the Magnetic Chain.2 Most of the inhabitants of Palmelo are practicing Spiritist mediums, and many of them are employed in civil service. Through linking hands, a group of mediums strengthens and heals each other, through channeling the flow of a vital spiritual fluid that washes through them, cleansing blockages, and attempting to settle karmic debt.3 Though the sanatorium was later closed by the Brazilian government, which objected to treatment solely through psychic, energetic forces, the inhabitants of Palmelo continue to heal and nourish each other by magnetic passes. Captain Gervasio’s Family is comprised of counterposed shots of mediums in trance describing “vast spiritual colonies” with images of modern Brazilian cities and architectural details. While Captain Gervasio’s Family focuses on the spirit architecture and Kafkaesque hierarchies of governmental offices, tedious procedures, statistical collections, and data analysis, Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter locates itself within the provincial, queer, and domestic. There are some final scenes of communal gatherings of mediums holding hands and channeling spirits, but most of the film is comprised of the domestic and private lives of two mediums in particular, Divino and Lázaro.

Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter, 2017. Video still. Digital video, color, three-channel sound, 30:28 min. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artists and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel.

One of the opening scenes shows Divino, the first of the shadowed men that we see in Studies, repairing a torn chromolith of Saint Lazarus. This act of healing echoes the significance of St. Lazarus as the representation of illness and recovery; his body is depicted scarred by leprosy, and he is known as the one Jesus raised from the dead. As Divino works with careful fingers, he speaks of how this saint had the power to cure him of childhood sickness. The film cuts to a similar print of St. Lazarus hanging on a wall, but this image is whole, and a different man—Lázaro, who shares the saint’s name—is making coffee. The body is broken here, cut by light, by the fragility of paper, by the frame’s composition. Sunlight filters through the plant’s leaves, marking the sitter’s limbs with golden coins and dark scars like the ulcers of leprosy dotting the body of St. Lazarus.

Tamar Guimarães wrote the book A Man Called Love: Reading Xavier about a Spiritist leader, Francisco Cándido Xavier. Speculating on Xavier’s femininity and queer sexuality, Guimarães writes, “Here I sketch out an argument—a hesitant and half suggested question: Could the notion of a porous body be a remainder of what is not reconciled in the subject’s negotiations with modernity?—An open body rather than the hermetically sealed, autonomous body of the Enlightenment?”4 Divino and Lázaro are porous bodies, open to the shadows of plants and history that flicker across their flesh and the spirits who pass through them, fleetingly palpable as groans, sharp intakes of breath, clucking and brrring of the lips, and descriptions of visions. Both Divino and Lázaro are connected through spiritual tissue and through their shared occupation of space; we see them toward the end of the film together at the Sanatorium, engaged in a communal activation of the Magnetic Chain. There they exchange a long, meaningful glance. They are also mysteriously connected in their affinity for St. Lazarus and are shadowed by the same canopy of peacock flower trees.

Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter, 2017. Video still. Digital video, color, three-channel sound, 30:28 min. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artists and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel.

In many images of St. Lazarus, he is accompanied by a dog or several dogs, who lovingly lick his open wounds. Lázaro, whose voice narrates Guimarães and Akhøj’s film, says, “I wanted a dog like that, my father kept going to the neighbors until he managed to get a puppy like that. He was my companion.” This intimacy punctuates the suffering and alienation Lázaro describes feeling because the human community could not accept the spirit voices he heard and instead saw him as “sick.”

Guimarães writes that Xavier was forced to lick the open wound of his godmother’s favorite child. Noted by Guimarães as a moment of childhood abuse, it echoes in the film in a different way. Looking closely at the chromolith of St. Lazarus, we see the dog’s soft tongue licking the wounds of St. Lazarus in a moment of interspecies love and intimate care,5 a sensual probing of the porous body not unlike the saints who eagerly lap pus from wounds of the sick or the ecstatic visions of mystics who insert their tongues, fingers, and even whole arms inside the vaginal chest wound of Jesus Christ. This dog of St. Lazarus reappears in the film in the city of Palmelo, trotting alone down an empty street, Avenida Allan Kardec (named after the founder of Spiritism). The scene forms a non-human bridge between the only physical encounter between the two characters, Lázaro and Divino. Solitude permeates the desolate city of Palmelo, populated by awkward outcasts whose most intimate interactions are mediated by other species or spirits. The opening scene shows Divino regarding a praying mantis that walks upon the hairy prairie of his arm with gentle curiosity.

Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter, 2017. Video still. Digital video, color, three-channel sound, 30:28 min. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artists and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel.

This companion, the praying mantis, speaks to the enmeshment of life through the physicality of its form, a mimetic insectoid interpretation of a tree branch. In Donna Haraway’s book Staying with the Trouble, she describes a cartoon, xkcd, by Randall Munroe, that shows two people discussing an orchid that evolved to lure and mate with a male bee that is now extinct. “The flower collects up the presence of the bee aslant, in desire and mortality. The shape of the flower is ‘an idea of what the female bee looked like to the male bee…as interpreted by a plant.’”6 Such interpretations abound in our contemporary, digital world, where humans must prove to machines that they are humans in order to detect fraud, and where machines create fake news stories with real news effects. One method of authenticating one’s humanity is the transcription of CAPTCHA codes— those blurry, distorted pictures of numbers and letters.7 Dr. Luis von Ahn, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, and a team of researchers created reCAPTCHA, a startup company he sold to Google for an undisclosed sum in 2009. ReCAPTCHA harnesses the unwitting free labor of millions of people for Google Books or Google Maps when these people, intent on proving their fleshy status, transcribe blurry photos of words and numbers sourced from digitized old books or address numbers. This labor is usually an intensive and expensive three-stage process involving bitmap photography of the text, encoding into optical character recognition (OCR), and human correction of mistakes. “By filling out a captcha, [humans] were providing unpaid, involuntary and ‘fundamentally mindless’ labour. They had to become robots—which translates as workers—in order to prove they were human.”8

Donna Haraway uses the word sympoiesis, which was coined by M. Beth Dempster in 1998, to describe generative acts of becoming-with. Sympoiesis replaces the auto in self-making, recognizing that all of the partners making up holobionts (etymologically, “entire beings” or “safe and sound beings”) are symbionts to one another. There is no hierarchy in which one, usually because of scale or egocentricity, is considered the host and the other the dependent. Instead, scientist Lynn Margulis forwarded a theory of symbiogenesis where new bodies come to exist not through competition and survival of the fittest, but rather through uneasy, long-lasting intimacies, interspecies-interkingdom mergers where one organism partially digests, partially assimilates, and partially transforms with other organisms, forming new multicellular forms.

In the event that became known as Pizzagate, narrative and reality were intertwined in sympoietic relation. Fake news of Hilary Clinton’s involvement in child pornography (aka Cheese Pizza) was generated by Twitter bots—automated accounts that are programmed to retweet, repost, or even police and report accounts based on recognition of specific keywords and hashtags—along with real people who found and reposted the tweets, and other real people (based mostly in Russia and Eastern Europe) who consciously controlled “shepherd” and “sheepdog” accounts that amplified these automated tweets. It is astounding that such a ridiculous story could take on enough believability to “become real,” but if reality is measured by physical effects, then Pizzagate indeed was “real.” Real enough for Edgar Welch to visit Comet Ping Pong with an AR-15 rifle intent on liberating exploited children; real enough to spark an episode of PTSD in an ex-student of mine, leading him to wield a piece of glass in a supermarket in Sylmar, California, whereupon he was shot dead by a security guard; and real enough to aid Donald Trump’s election to US president. Strangely enough, the visual arts’ strength in narrative was harnessed to authenticate right-wing claims: Marina Abromovic’s invitation to John Podesta’s brother Tony to attend a “Spirit Cooking dinner” became proof that he was a Satanic occultist, and Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture The Arch of Hysteria (1993) in Tony Podesta’s art collection was used as proof linking the Podesta brothers to Jeffrey Dahmer, who posed the body of one of his murder victims in a similar composition.

Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter, 2017. Video still. Digital video, color, three-channel sound, 30:28 min. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artists and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel.

The strategy of drawing associative connections between formal similarities has a long history in art, perhaps most notably in Aby Warburg’s unfinished Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29), which places similar gestures and formal compositions next to each other, irrespective of the time periods and contexts in which these images originally appeared. Indeed, it is the organizing principle for this essay and for my artistic method of thinking and research. So it is with great unease that I notice the use of this strategy to fuel conspiracy theories and fake news generated by the right-wing. Yet the recognition of visual similarities also has its histories of resistance within colonization. As peoples dislocated from their homelands and coerced to convert to Christianity, African slaves syncretically associated their local gods with Catholic saints who shared specific visual attributes.

The leprosy-scarred St. Lazarus is syncretically aligned in African-diasporic religions such as Umbanda, which is also practiced in the city of Palmelo, with Obaluaiye (also known as Babalú-Ayé), the god associated with infectious disease and healing.9 Obaluayie has roots in the Yoruba god of smallpox, Shakpana or Shopona, a god of contamination covered in red infective sores, shielded from gaze by a raffia cloak that makes the god seem, when whirling around or standing perfectly still, part vegetal and part whirlwind, mystical and inhuman. Obaluaiye is a porous body, riddled with open sores, a figure that rose to power during the European colonization of Africa and its diaspora. In Santería, the ritual altar presents different vessels—in the form of soup tureens (soperas), ceramic water storage jars (tinajas), terra cotta or iron pots, roof tiles (teja), basins (palangana), platters (fuente), wooden vessels (bateas), metal boxes or cans, and calabashes. Each represents a specific god and is distinguished by distinct colors and aesthetics associated with each god. These vessels house the sacred stones or other objects—physical manifestations of the spirit. Many of the vessels, such as the soperas, are made of porcelain or white earthenware china and harken back to Cuba’s colonial past and its European aristocracy’s collections of china as status tokens in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.10 But the bisque-fired terracotta pot that houses Babalú-Ayé is unglazed and perforated with holes; these holes mirror the holes in the flesh and symbolize the difficulty of containing illness. The permeability of the raffia cloak punctuates this reminder. During the “scramble for Africa,” Shakpana, previously a lesser-known deity, rose to major significance as smallpox spread along with the disease’s visibility in public health campaigns and the establishment of “tropical medicine” as a field.

Robert Farris Thompson writes, “British colonial authorities banned the cult in Nigeria in 1917 when Obaluaiye priests were accused of deliberately spreading smallpox. But members of the cult… refused to be intimidated. They took their worship underground. They worshipped Obaluaiye under different names… The strength of his lore in modern Nigeria is illustrated by the continuity of the old belief that it was dangerous to call him by his name, for one would thereby spread his dread disease, shoponnon (smallpox).”11

Obaluaiye is sometimes represented by a thorn. This could be seen as the typical colonialist fear of contamination, or it could be the opposite, a natural, plant-formed inoculation device. In 1774, during a smallpox epidemic in England, physicians noted that milkmaids were among the few who did not bear the ravages and scars that marked the faces and bodies of other smallpox survivors. “Folk knowledge held that if a milkmaid milked a cow blistered with cowpox and developed some blisters on her hands, she would not contract smallpox even while nursing victims of an epidemic.”12 From this practical knowledge, laypeople experimented: one farmer used a darning needle to drive pus from a sick cow into his wife and children. Known as variolation, this evolved to become what we now know as modern vaccination. Inoculation does not come from professionalized medical experimentation but rather from observation, interspecies relations, and a chain of shared immunity, not unlike the Spiritist Magnetic Chain of Palmelo.13

Obaluaiye’s raffia-covered body is formally echoed in Carolina Caycedo’s sculpture, Big Woman/Mujer grande (2017), a witchlike, folk female figure with a painted wooden mask for a face. She is suspended within a permeable cloak of fishing net and dry cattails, plantain fibers, and vines that trail in a tangled excess onto the wooden floor. The voluminous fabric of her body is rotund and basket-like; she seems to hover protectively, omen-like, promising plentitude yet, perhaps, righteous retribution if one transgresses upon the bounty of her body.

Carolina Caycedo, Big Woman/Mujer grande, 2017. Wooden mask, handmade fishing net, handmade wool hammock, nylon fishing net, fabric, dry cattails, dry plantain stem fibers, vine, rope, 85 x 26 x 62 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council.

Big Woman/Mujer grande is one of several sculptures in Caycedo’s exhibition El hambre como maestro/Hunger as Teacher, at Commonwealth and Council. The works in the exhibition are part of Caycedo’s ongoing project, Be Dammed, which addresses socio-environmental impacts of dams in collaboration with various riverside communities affected by dams. The project also honors several environmental activists working for water rights and protections (including many who have been murdered for their activism)14 Many of Caycedo’s other works also involve fishing nets as their primary material and form. These cast-off nets are gathered from the riverine communities Caycedo works with, and their materiality represents a porous way of thinking about bodies and boundaries as a membrane, a malleable structure that allows liquid to flow through it. According to Caycedo, the fishing net stands as a symbol for “food sovereignty and autonomous economies… To throw a fishing net affirms the river as a common good.”15

But I encounter this fishing net within another web of symbolism. Taken out of use, it has moved from its original context and relation to food sovereignty into the realm of aesthetics. Here, the fishing net lends its physicality to the structure of a sculpture. It materially speaks the content of the work, and the history of its origins has immaterial cultural capital in its declaration of a leftist, community-affirming politics that the art market values, even when these leftist politics are in contradiction with its own funding. Caycedo’s haunting sculptures play with the shiftiness of materials, creating visual traps of meaning that challenge the very economies that make the lives of those it represents precarious, while still being enmeshed within that same economy. What does it mean for such materials to move from being used as a tool of survival to playing a pedagogical role in raising art viewers’ awareness of political water-rights issues, activating an emotional and aesthetic stake in the issue through its materiality, and being an object collected by private collectors and museums? To be clear, I raise these questions of economics not to take Caycedo to task, for I deeply respect her ethics, political motivations, and admire the aesthetic strength of her work. Rather, these are questions relevant to all cultural production, for none of it takes place outside of the systems and history of its making, and the question of how to negotiate such creative, critical artistic production is an ongoing one. Yet it is an “impossibility” we must persist in and insist upon imagining if we are to create, in Saidiya Hartman’s words, a “critical fabulation” of what was and is possible, weighted in the awareness that our“own narrative does not operate outside the economy of statements that it subjects to critique.”16 Caycedo’s work does this by moving between the material and immaterial, and by playing in the in-between realm through the signifier of the net, a malleable and porous membrane. Her work’s engagement with the economics and politics of water-rights contestation is echoed in how she traces the movement of meaning and value in material to immaterial forms.17 Interestingly, these movements also mirror value production in the world of finance.

From The Reverse Side of a Painting (1670) by Cornelius Gijsbrechts to René Magritte’s La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is not a pipe], 1928) to Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), the visual arts highlight how meaning production is tied to visual and linguistic representation through undercutting what usually appears neutral to us. By generating confusion between three-dimensional and two-dimensional representations of reality, or through introducing text as an alternate form of representation, these artworks question how realities and meanings are constructed, pointing to the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s concept of arbitrariness in the relation between the signifier and the signified. Franco “Bifo” Berardi describes this tearing apart of the signifier and the referent as dereferentialization, a gesture he observes in both twentieth-century experimental poetry and in neoliberal economic changes within the last three decades of the century.

Carolina Caycedo, To Drive Away Whiteness/Para alejar la blancura, 2017. Hand-dyed fishing net, lead weights, hand-dyed jute cord, plastic and glass bottles, liquor, banknotes, seeds, chili peppers, achiote, sand, dried kelp seeds, water (Pacific Ocean, Colorado River, and Los Angeles River), hibiscus, black beans, human hair, ginseng, paper, 89 x 136 x 107 in. Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

In financial markets, liquidity measures the trade-off between time and value. Cash, in countries with stable currency value, is considered the ultimate liquid asset, because it can be exchanged for goods and services with no loss of value. A house, on the other hand, traditionally represents less liquidity—it can be sold, possibly for an increased value, but the funds are not as readily available. In 1971, under President Richard Nixon, the U.S. dollar abandoned the gold standard, and the value of U.S. currency, no longer tethered to a physical referent, fluctuates according to debt and speculation. During the 2007 to 2010 subprime mortgage crisis, properties became illiquid because they were bundled into stacks that obscured the actual value of material assets tied to them. Their value increased beyond their materiality through speculation, and their illiquid status was exacerbated by computerized technologies that increased the complexity and obscurity of how their value was determined. Berardi writes: “Because of the technological revolution produced by information technology, the relation between time and value has been deregulated. Simultaneously, the relation between the sign and the thing has blurred, as the ontological guarantee of meaning based on the referential status of the signifier has broken apart.”18

Water is sometimes spoken of as the last resource to be privatized, and its value comes from holding the right to choose who moves through it or what bodies—human, geographical, or corporate—it passes through.19 Water’s power comes from its potential movement and the restriction of that movement. In the physical world, a dam takes a material resource—a river—and abstracts it into immaterial (or less material) electricity that can be moved and displaced from its location, divorced from its origin and the community it sustains. But a river is a body that cannot be rerouted and controlled without a chain of effects. In their essay “Transfiguring the Anthropocene: Stochastic Reimaginings of Human-Beaver Worlds,” Cleo Woelfle-Erskine and July Cole use Eva Hayward’s transgender theorizing to rethink bodies as riverine ecologies and vice versa. They discuss Hayward’s consideration of “the body variously as a body of water—a river, which draws together all of the above and underground water in a watershed.”20 The body is more than what is visible on the surface, it is the vapor in the air, the subterranean wetness below; the body is not fixed any more than a body of water could be defined by the landmasses that surround it. In Hayward’s words, “The body, trans or not, is not a clear, coherent and positive integrity. The important distinction is not the hierarchical, binary one between wrong body and right body, or between fragmentation and wholeness. It is rather a question of discerning multiple and continually varying interactions among what can be defined indifferently as coherent transformation, decentered certainty, or limited possibility.”21 According to Woelfle-Erskine and Cole,“In river terms, rejecting a binary between fragmentation and wholeness refuses the dewatered, fragmented river that holds no salmon and leaves some farmers without irrigation water in dry years.”22

In the Magnetic Chain, illnesses are addressed in part through magnetic passes which remove the obstructions in the flow of vital fluid; these obstructions are what cause sickness. In a series of letters edited by John Pearson, in 1790, the purpose of treatment using animal magnetism (lebensmagnetismus) is to induce “crisis” through shocking the body into convulsion, “to remove obstructions in the humoral system that were causing sickness.”23

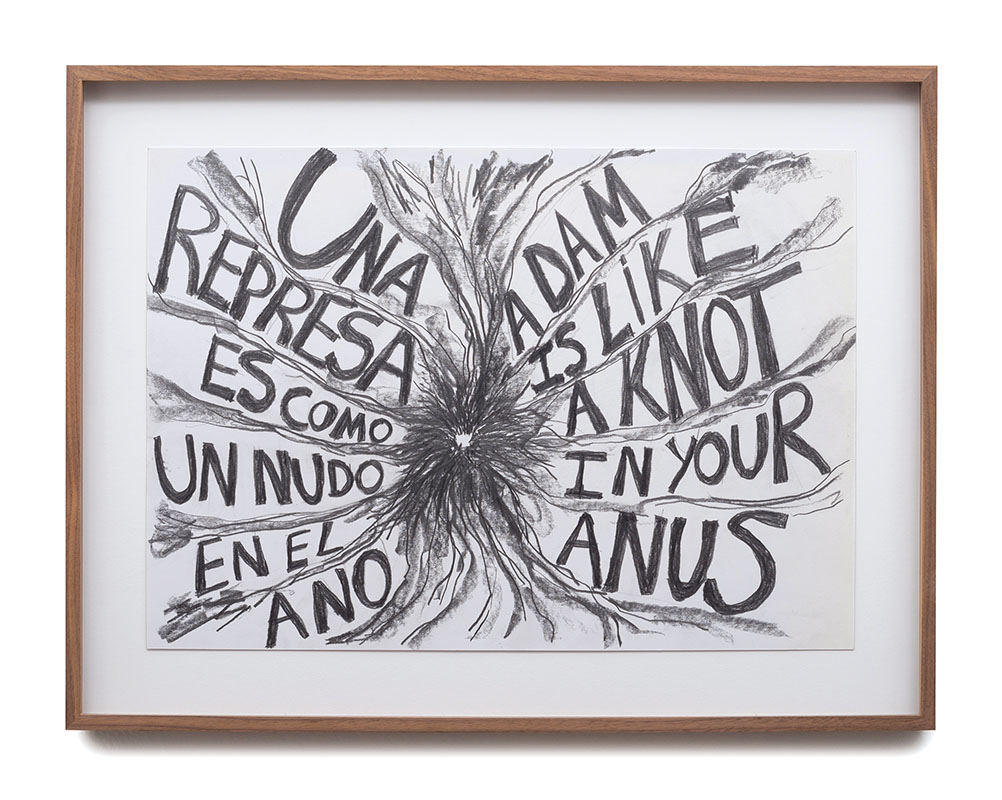

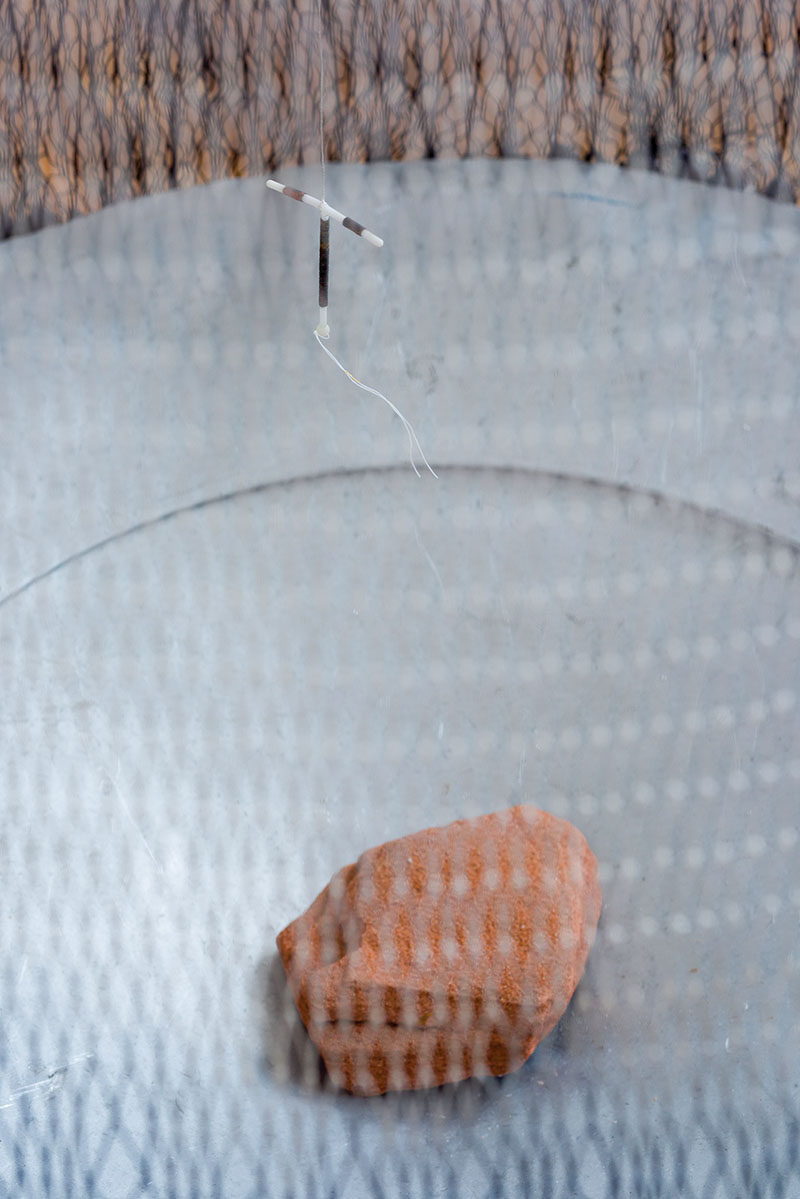

In Caycedo’s El hambre como maestro/Hunger as Teacher, the riverine movement of water through the land is likened to the human body, in its fluids and orifices. In Damn Knot Anus/Nudo represa ano (2016), a graphite drawing of a portal-like wrinkled or hairy anus graphically shouts, in Spanish and English, the words: “Una represa es como un nudo en el ano /A Dam is like a knot in your anus.” Taken from Caycedo’s interview with Kogui indigenous spiritual leader Mamo Pedro Juan, who passed away June 2017, this memorable phrase speaks to the pressure that a dam creates in cutting off water from the communities that depend upon it. In Undammed/Desbloqueada (2017), Caycedo’s own body—its fluids and reproductive potential—is referenced in the copper intrauterine device that hangs suspended like a totem within one of her fishing net sculptures above a metal pan used for mining gold. The pan is empty of gold and the wealth contained within this pan is the land: “a chunk of Navajo sand-stone.”24

Carolina Caycedo, Damn Knot Anus/Nudo represa ano, 2016. Pencil on paper, 15 1⁄2 x 20 x 1 1⁄2 in. Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Control over water, land, and reproductive rights are ways that sovereignty has historically expressed its power, and this is the rhetoric used both by the indigenous communities and the Brazilian businesses and government they are fighting against, who claim that the power harnessed by dam-controlled waterways will finance and power their nation in a way that does not rely on foreign imports of oil or coal. Much of the energy generated by dams actually goes to power the mining industries converting raw materials into metals. These are often foreign companies, such as the American company Alcoa, which has a heavy presence in Brazil and Suriname. Bauxite ore, used to make aluminum, is mined at La Providence. In the eighteenth century, La Providence was the last Labadist outpost in Suriname; it was this communal, anti-materialistic religious community that awoke Merian’s curiosity, as its members returned from the colony with specimens of exotic flora and fauna and descriptions of the environment there.25 “In the 1960s Alcoa dammed the river just past the site of La Providence to create energy to process the bauxite, flooding [what was once] maroon territory and creating a vast lake where, when the water level sinks, the dead trees rise.”26

This reanimation of the dead trees that lie latent under the beguilingly calm surface of the dammed water brings to mind Christina Sharpe’s writing on oceanic memory. Thinking about those who died during transatlantic voyages—in which slaves were thrown or jumped overboard from ships— Sharpe reveals a haunting method of keeping time in the sea:

There have been studies done on whales that have died and have sunk to the seafloor. These studies show that within a few days the whales’ bodies are picked almost clean by benthic organisms— those organisms that live on the seafloor. My colleague Anne Gardulski tells me it is most likely that a human body would not make it to the sea floor intact. What happened to the bodies? By which I mean, what happened to the components of their bodies in salt water? Anne Gardulski tells me that because nutrients cycle through the ocean (the process of organisms eating organisms is the cycling of nutrients through the ocean), the atoms of those people who were thrown overboard are out there in the ocean even today. They were eaten, organisms processed them, and those organisms were in turn eaten and processed, and the cycle continues. Around 90–95 percent of the tissues of things that are eaten in the water column get recycled. As Anne told me, “Nobody dies of old age in the ocean.” The amount of time it takes for a substance to enter the ocean and then leave the ocean is called residence time. Human blood is salty, and sodium has a residence time of 260 million years. And what happens to the energy that is produced in the waters? It continues cycling like atoms in residence time.27

Carolina Caycedo, Undammed/Desbloqueada, 2017. Hand-dyed fishing net, lead weights, metal gold pan, Navajo sandstone, copper T IUD, thread, rope, 64 x 19 x 19 in. Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Carolina Caycedo, Undammed/Desbloqueada (detail), 2017. Hand-dyed fishing net, lead weights, metal gold pan, Navajo sandstone, copper T IUD, thread, rope, 64 x 19 x 19 in. Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

The shadows in Guimarães and Akhøj’s film serve to remind us of residence time, of this atomized presence of the death and life that came before us. In the canopy of trees and plants that were used by African and Indigenous slave women to abort their children so they would not be born enslaved, these sylvan shadows could be the souls of the past, reminding us of histories that remain sublimated but present. In the fairytale The Fisherman and his Soul, by Oscar Wilde, a fisherman falls in love with a mermaid, whom he catches in his fishing nets and wants to join. But he is burdened by his human soul. He meets a red-haired witch who gives him a knife with a handle of green viper skin and says, “What men call the shadow of the body is not the shadow of the body, but is the body of the soul. Stand on the sea-shore with thy back to the moon, and cut away from around thy feet thy shadow, which is thy soul’s body, and bid thy soul leave thee, and it will do so.” The tale goes on to tell of the devastation caused by foolishly thinking one could separate oneself from one’s shadow, conscience, soul, or past. The story of the 2007–10 financial crisis is a similar tale of an ill-fated separation between the material and immaterial worlds.

In the eighteenth century, when Maria Sibylla Merian journeyed to La Providence and Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname, she saw a very different pre-flooded geography, proximate in space to both Palmelo, Brazil, and the South American locations of the riverine communities Caycedo has worked with.28 In 1699, Merian encountered a Dutch colony obsessed with sugar production. When Merian heard about Suriname from her Labadist religious comrades, she sold her paintings and drawings to raise the funds to join the Dutch colonial expedition, so that she could travel and study the metamorphosis of bodies in a new environment. Merian’s scientific illustrations were path breaking because they studied organisms in their contexts, rather than as isolated specimens. This style of visual representation, showing the insect or animal and the environment that sheltered and fed it, became the scientific status quo a century after her death. It is an anachronism to describe her representations as ecological, since that concept was only articulated much later. In 1866, the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel used the term “oecologie” in his book Generelle Morphologie. “Oecologie” or “ecology” comes from Greek “oikos,” meaning “household organization,” and describes the interaction of creatures and their surroundings. Though complicit with colonialism as part of the Dutch colonial expedition, Merian’s drawings and notes reflect more than a capitalistic eye toward an insect or plant’s possible profitable exploitation. Her careful, invested interest described the effects, dependence, and co-constitution of organisms in a shared ecology, of which humans, and their plantation economies, were inextricable parts. The meshed ecology that Merian painted was perhaps a visual depiction of what feminist physicist Karen Barad calls “intra-action,” a mutual constitution of entangled agencies.29 Instead of seeing organisms as separate, pre-existing beings, Merian, like other female scientists—Barad, Haraway, and Margulis—observed how the physical forms of life were co-constituted by their relations to each other, relations where lines between sexuality, survival, and mimicry become blurred.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Peacock flower plant and insects, Amsterdam, 1719. Published in Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam). Counterproof etching with watercolor (hand coloring), 20 1⁄4 x 13 3⁄4 in. © John Carter Brown Library, Box 1894, Brown University, Providence, R.I. 02912.

Though an ecological view of intermeshed, sympoetic life has its political ideals in theories like Gaia and a recognition of how one’s own responsibility and livelihood is interconnected in a web of cause and effects, the financial crisis of 2007–8 is another example of intra-action. In a 2016

Fortune article, Geoffrey Smith writes of Deutsche Bank,

Too Big to Fail was always a bit of a misnomer. What really makes a bank a risk to the financial system as a whole is the degree to which it is interconnected with other institutions, i.e., its ability to spark chain reactions of non-payment if it should ever default. By this measure, Deutsche is frighteningly indispensable. It’s a counterparty to virtually every major bank in the world, in virtually all asset classes. [An] illustration from an IMF report in June gives you some idea. This is why I argued yesterday that the German government, which together with the European Central Bank is responsible for supervising Deutsche, would be highly unlikely to let it fail in a disorderly manner à la Lehman Brothers.30

In Spiritism, this enmeshment of life is seen as a form of animal magnetism, the invisible natural force that flows through all animate beings. Guimarães and Akhøj’s Studies for a Minor History of Trembling Matter shows a Spiritist session where members clasp each other’s fluttering hands, their bodies racked with spasms and shudders of the energetic ripples that flow through the linked chains of their bodies. As the session comes to a close and people sit in peaceful clusters, a rain shower pours down outside, a physical manifestation of the spiritual fluid that flows through them.

Perhaps the vital fluid that connects all living beings could be seen in contemporary terms as debt. Debt, a promise of our future labor, our future time, interconnects us as individuals, as networks, as countries. The institution that gathers the most future time of other countries, therefore, has, by virtue of its interconnection and the intra-active devastation it would wreak if it were forced to go bankrupt or pay its debt, the right to insolvency, the right to refuse to pay its debts, the right defy time. “German banks have stored Greek time, Portuguese time, Italian time and Irish time, and now the German banks are asking for their money back…Is the money that is stored in the banks my past time (the time that I have spent in the past) or is it the money that ensures the possibility of my buying a future?”31 This debt, made up of our past and future time, is the vital fluid, the invisible liquid that we are submerged in; it defines our relations.

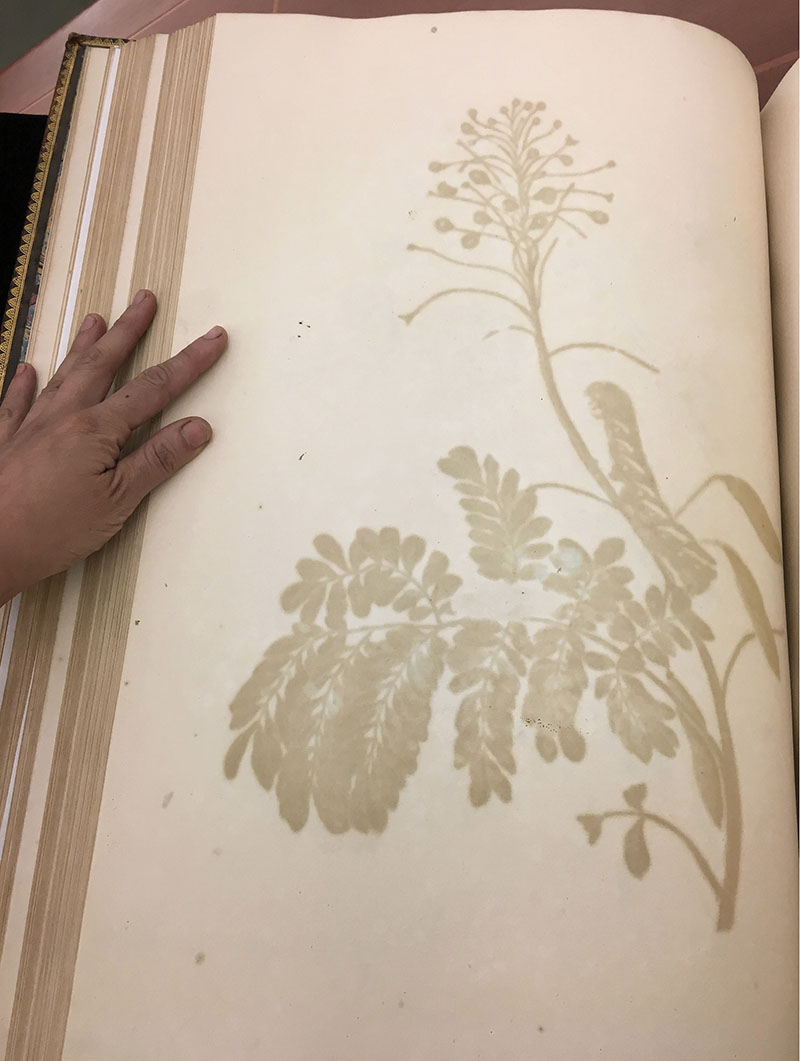

I first encountered Maria Sibylla Merian’s book Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam at the Huntington’s Visual Voyages exhibition. Curator Daniela Bleichmar writes that this copy of Merian’s book used a unique method of printmaking, called counterproofing: “The printer would take a freshly printed page just off the press, put it on top of a blank sheet of paper, and run both together through the press to produce a print from another print rather than from a copperplate. The resulting counterproof had a much lighter impression than a regular print and, when colored by hand, looked much more like an original drawing than a regular copper plate did.”32

This mirrored, softer copy has a third unintentional impression created by the acidic burn of the pigments reacting to the paper over two centuries of time. What we are left with on the backside of the paper is a partial shadow of the original. This ghostly silhouette reminds me of a similar specter I saw in the Smithsonian archives in 2009, when looking at John Stedman’s The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796), illustrated by William Blake. The image that haunted my mind was the burned shadow of Blake’s engraving, The Execution of Breaking on the Rack. The print shows two slaves; one is outstretched on the ground, while the other bends over him, arrested in the labor of bludgeoning his bones with a stick. The original image is as grotesque in its violence as Stedman’s descriptions. But it’s the burn that haunts me, for its possibilities, what Hartman describes as the “impossible goal”—listening for the unsaid, looking for what is beneath the submerged surface of water, the imagined lives outside of their limited appearances and disappearances in the official histories of those in power.33

In this imprint, the figure standing over the one outstretched on the ground could be running to his assistance, hands thrown up in horror, or, enlisted in the brutality of torture, the standing figure could be theatricalizing the gesture of breaking, trying instead to find ways of minimizing the pain.

Counterproof burn of Maria Sibylla Merian’s Caesalpinia pulcherrima (Peacock flower plant)

in Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam). The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Photo: Candice Lin.

Merian’s book makes tangible the impressions each generation of image-making leaves upon another. Softer, blurred lines or pigment reacting with paper, foxed with age, the content of these histories are incomplete but can neither be disappeared nor fully imagined into being. Immaterial histories and the violent legacies that live on into the present erupt into the physical in liminal forms: the molecules of sodium in the water we drink, epigenetic illnesses, and, of course, the societal institutions, such as prisons, that continue the same inequities of power and slavery from which they spring. This is the “history of present” that Saidiya Hartman writes about:

As a writer committed to telling stories, I have endeavored to represent the lives of the nameless and the forgotten, to reckon with loss, and to respect the limits of what cannot be known. For me, narrating counter-histories of slavery has always been inseparable from writing a history of present, by which I mean the incomplete project of freedom, and the precarious life of the ex-slave, a condition defined by the vulnerability to premature death and to gratuitous acts of violence. As I understand it, a history of the present strives to illuminate the intimacy of our experience with the lives of the dead, to write our now as it is interrupted by this past, and to imagine a free state, not as the time before captivity or slavery, but rather as the anticipated future of this writing.34

Caycedo’s sculptures and Guimarães and Akhøj’s films endeavor to visualize an intimacy of our present interwoven with the dead—the water rights activists who died or were killed for their actions and beliefs and the mediums who channel the voices of a Brazilian past grappling with its modernity. Though embroiled within the same systems of finance, the same “grammar of violence,” there is a material and haunting “terrible beauty” in both Caycedo’s and Guimarães and Akhøj’s works, which use shadows and nets to point to what is not present, to strive, against impossibility, pessimism and hopelessness, to imagine a future that is not already owed to a German or U.S. bank.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at Portikus, Frankfurt; Bétonsalon, Paris; and Gasworks, London.