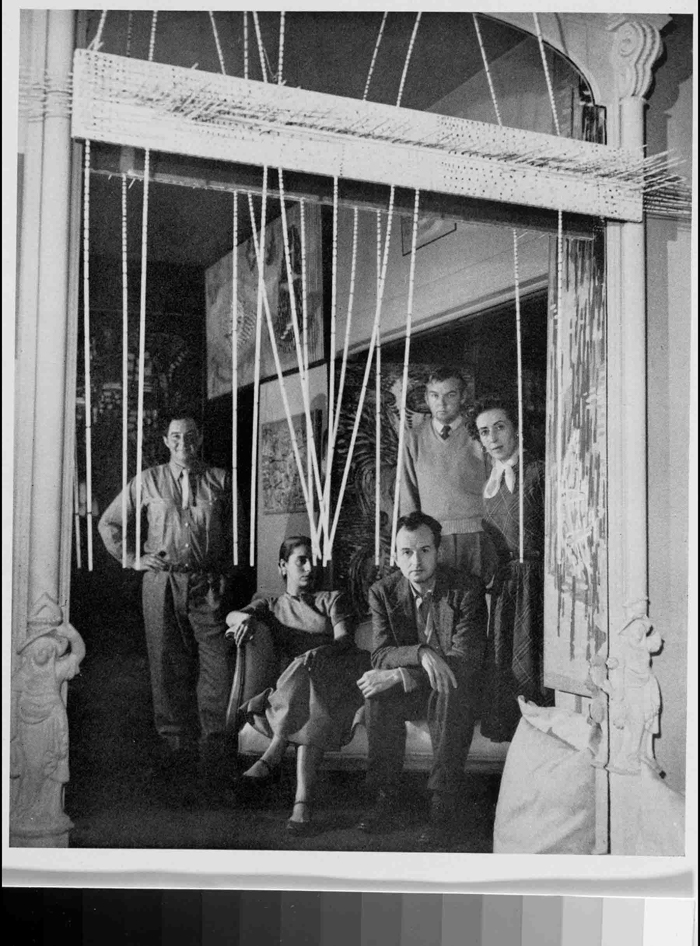

Left to right: Gordon Onslow Ford, Luchita Hurtado, Wolfgang Paalen, Lee Mullican, and Jacqueline Johnson in Onslow Ford’s home on Telegraph Hill, San Francisco, 1949. (The suspended sculpture is one of Mullican’s “tactile ecstatics.”) Reproduced as the frontispiece of the Dynaton 1951 exhibition catalog.

“This is an anxious moment for the work,” Lari Pittman says of paintings by his former teacher Lee Mullican, which, after a period of neglect, have now recovered an ability to speak to younger artists. For the paintings to continue to gain appreciation, Pittman adds, “ . . . a critical language has to attach itself to the work”— one that goes beyond the artist’s stated intentions.1

Developing a critical language for such an eccentric artist might be an interesting challenge. Perhaps this essay can constitute a first step in that direction. Mullican (1919- 1998), an abstract modernist painter born in Oklahoma and familiar with Southwest Native American blankets and sand painting, became associated with two renegade Surrealist painters—Wolfgang Paalen and Gordon Onslow Ford. The apex of their collaboration was the famous Dynaton show at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1951, virtually at the inception of Mullican’s career.2 At the same time, Mullican became known for painting with a printer’s ink knife or putty knife, with which he applied ridges of paint to the canvas.

One would first have to clear away a couple of problems that attach to the work, which might in the process infect any critical language so that it might itself become problematical.

First is the enormous range and stylistic diversity of the work, some of which is semi-figurative and some of which looks like it might have been done by different artists. Mullican remarked, “At times it even worries me that it’s seemingly all so different, and I can only hope that one day it will all…fall into place as really being mine.”3 This variety makes it difficult to arrive at internal criteria by which to assess which are the stronger and weaker pieces. It has been suggested that the work is uneven, but again, the range of the work makes such judgments seem subjective.4

This situation is exacerbated by another problem—the invisibility of much of the work, particularly that of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Apparently, there is a lot of it—enough to “fill two museums, at least,” for Mullican was a prolific artist.5 Some work is still in Mullican’s studio, some at UCLA, where he taught for many years, some in a Culver City warehouse, some in Marc Selwyn Fine Art gallery. The recent exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, An Abundant Harvest of Sun, focused on the 14 years before 1960; only two of five rooms sampled work from the latter 38 years of his career.6 A show at Selwyn gallery shortly afterwards displayed ten large canvases from the 1960s.7 Apparently, the later work even includes some computer graphics and ceramic sculptures.

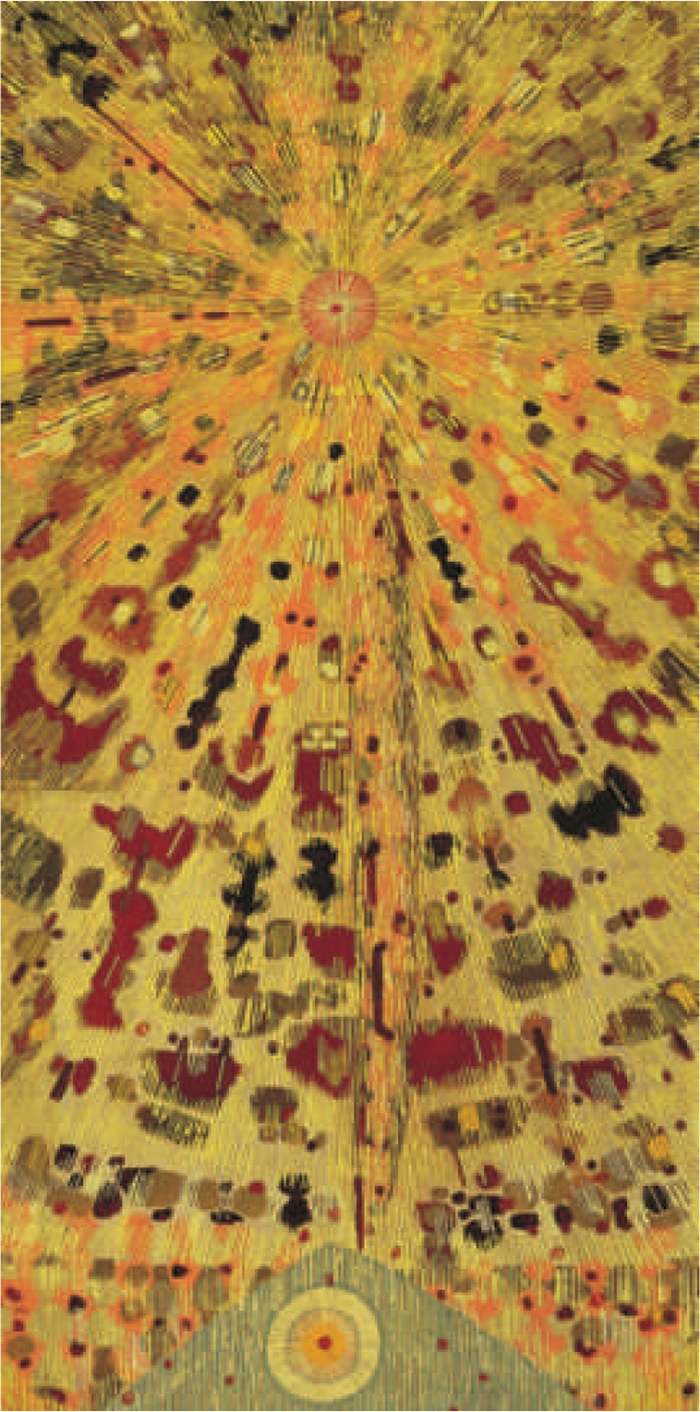

Still another problem concerns “automatism,” originally a Surrealist technique described by André Breton as an attempt “to express, either verbally, in writing or in any other manner…the dictation of thought, in the absence of all control by the reason.” To access the unconscious, Breton advises, “Write quickly, without a preconceived subject, fast enough not to remember and not to be tempted to read over what you have written.”8 Mullican said frequently that he was doing “automatic” painting and Onslow Ford—who, as a former Surrealist, ought to have known—confirmed it. The problem is that if one looks at the work—say, The Ninnekah from 1951—it seems carefully planned and executed. The ridges of paint (Mullican called them “striations”) radiate with precision from a central point and the colored blobs of the underpainting have a radial orientation as well. What part of the painting was done by automatism?

Lee Mullican, The Ninnekah, 1951. Oil on linen, 50 x 25 inches. Collection Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University. Marie Eccles Caine Foundation Gift. © Estate of Lee Mullican.

At any rate, this attempt to tap the unconscious leads, where it is successful, to the “inner space” that Mullican sought through his work, and which belongs to “the spiritual in art”— a not unproblematic domain usually associated with abstraction.9 Are all Mullican’s canvases equally spiritual? (Were they equally successful in reaching the inner space?) He describes the process of making them as a sort of meditative exercise but some boil over with energy, tumult, and perhaps even anger—and some of these may be among the stronger works.

Paalen and Onslow Ford described Mullican’s work in flowery poetic language but, since they knew the work well, there is probably some germ of truth in what they wrote. Hence another problem: What did Onslow Ford mean by the qualities of “transparency” and “weightlessness” in Mullican’s work? To what did Paalen refer by saying that “Air is the element for Lee, and all it carries, pollen, feathers, the dreams of birds and spikes of stars and the holy nest of winds”?110

These problems are like knots on a string, to be picked apart one by one. But in another sense the knots overlap, so that picking one apart may loosen the others. Let us start with automatism.

Paalen and Onslow Ford had joined the Paris Surrealist group in the late ‘30s and took refuge during the war with other Surrealist artists in Mexico. Onslow Ford moved into the countryside and lived among Tarascan Indians. Paalen went into collecting native antiquities in a big way while editing an art magazine, Dyn, in English and French, a copy of which Mullican had picked up while in the army in Hawai’i. By this time, both Paalen and Onslow Ford had resigned from the Surrealist group and were trying to sort out, through their work, which elements of the Surrealist program to keep and which to reject. After the war, both moved to San Francisco where Onslow Ford was attracted to Mullican’s work. Paalen’s and Onslow Ford’s form of sophisticated primitivism connected with Mullican’s interest in Native American design. An interview with Mullican suggests that the two former Surrealists tried to take their younger colleague in hand.

Interviewer: So did you feel in a sense that they adopted you? Mullican: Exactly. [They tried] certainly to guide me and educate me…I have a feeling that Paalen was having great difficulty with me. We had nothing in common as far as background goes. I was closer to Gordon [Onslow Ford] and Jacqueline [Johnson, his wife] and I had known them longer…I’m not sure just what [Paalen] thought about me…[it was] very difficult because of his European heritage…Someone from Oklahoma just had to be a little confusing to him.11

One consequence of this association was the Dynaton exhibition of 1951. Another was that Paalen’s marriage, already on the rocks, broke up and his wife, the Venezuelan painter Luchita Hurtado, began to live with Mullican and later married him.

They wanted to dissociate themselves from Surrealism. They were both Breton Surrealists. Now, I didn’t have that background, so it didn’t really bother me. But that was a primary urge for creating what they did. They wanted to get away from this whole idea of dreams and illustration, etc., like the early Surrealists. – Mullican12

This background will help show that Mullican, although influenced at a remove by Surrealism, was not a Surrealist and did not “share a Surrealist past,” as has been claimed.13 The model for the younger Surrealists in France (Onslow Ford, Roberto Matta, and Esteban Francés) had been Yves Tanguy; for Mullican it was Paul Klee, the Klee who described a line going for a walk.14 Mullican too was a linear artist, and his work would become as diverse as Klee’s. Compare his description of automatism with that of one who had worked with the Paris group.

The way to enter the unknown in painting is to work faster than thought, spontaneously, being conscious of what happens as it happens. In this way there is a chance that more than can be thought about will be expressed, and that the forces of nature will come into play . . . Images that appear at speeds only a little faster than thought may still be full of associations with the known, but as images speed up, known images give way to linear images which have a life of their own. – Onslow Ford15

Here we find a mastery of the inner subject that comes forth from formal techniques producing canvases of power and inventive subjectivity. What are the clues to this inner-depiction? Certainly, action is an important element: action comes from automatism be it slow or racing.16

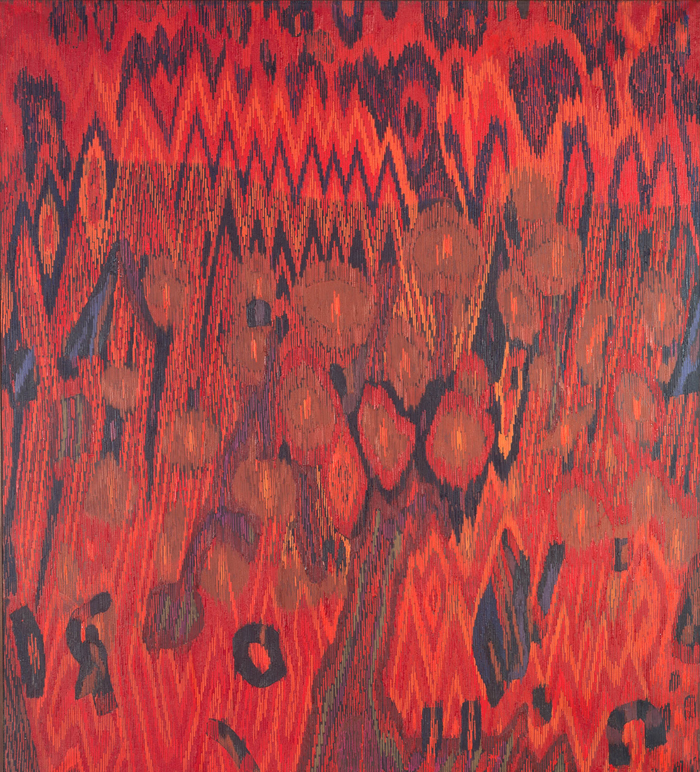

Lee Mullican, Magic Night, 1966. Courtesy of Smith College Museum of Art. © Estate of Lee Mullican.

Most people think because it is so tight and looks so planned, the strokes [striations] do, that it isn’t automatic; and yet it certainly is. And it changes, and I find myself at times having to slow down. Otherwise, it will just run away with me. – Mullican17

The notion of a slow or restrained automatism, though it might have been fruitful to Mullican in practice, would be almost a contradiction in terms to a Surrealist. It would subvert the whole purpose and goal of automatism. Mullican’s broader definition of the term seems rather to refer to a meditative process.

I realized that when I was drawing, I really wasn’t thinking about anything . . . I did not have, quite often, any preconceived ideas of what I was going to be doing other than just what had happened in the drawings before that . . . This automatism was later developed in my painting.18

Once automatism is defined as absence of thought, the striations are perfectly consistent with it because it does not take much thought to put them on the canvas. The early striations seem quite carefully applied, either radially or in a drizzle of parallel lines, but in the ‘60s, they begin to break up and spew forth like a tangle of matchsticks. Typically, Mullican painted with the canvas laid flat on a table, turning it sideways or upside down to continue to work on it. Wax was mixed into the oil pigments for quick drying and to give them body.19 By the ‘80s he was practiced enough at rhythmically dabbing on striations for an observer to note “rapid stabs of line with a printer’s ink knife.”20

The effect of the striations is at once strikingly original and vaguely reminiscent of earlier modernism. Peter Plagens, reviewing a 1969 show at UCLA, found that “the overall feeling is one . . . of Van Gogh’s Starry Night and/or Indian blankets, within which there are bits of ‘figuration.’” Mullican himself noted “the impressionism of applying strokes of color,” and one also thinks of Paul Signac’s divisionism, though there is no attempt to reconstitute light through color. For Roberta Smith, “the sheer decorative glimmer” of the sunbursts recalls Klimt’s gold paintings. Perhaps the zaniest comparison—but one apt in terms of the energy dispersed—is to Futurist paintings such as Giacomo Balla’s Street Light (1909) for sunbursts such as The Ninnekah and Umberto Boccioni’s The City Rises (1910) for The Splintering Lions (1950), which seems to trace the paths of comets racing about the sky. Interestingly, Henry Hopkins, finding “a sun of planetary light source” centered in The Ninnekah, felt “this source is drawing energy to itself rather than dispersing it,”— a reversal of the sort to which Mullican’s paintings often give rise.21

Lee Mullican, Splintering Lions, 1949-50. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches. Nahum and Alice Lainer. © Estate of Lee Mullican. Photo courtesy of Mark Selwyn Fine Art.

At least in the early paintings, the striations constitute a perforated screen through which appears an abstract pattern. This screen may radiate from a center with immense centrifugal force, contained only by a section of the circle’s outer arc, or may consist of a drizzle of perfectly parallel vertical lines. Onslow Ford, writing about the early paintings, compared the striations to “Iron filings shaken over the nuclei of the canvas” and noted that:

Lines and marks float, and are held in balance by forces of attraction… Without warning magnetic winds blow up…The poles are splintered and multiple forces come into play. It demands great attention to navigate now…22

Or perhaps the broken lines represent incisions in the picture plane that allow whatever abstract entity waits beyond to view us.23 There are ink drawings consisting of subtle variations on the drizzle, and paintings such as Untitled (1949) traversed by looping black lines resembling canals or major thoroughfares on an aerial map. (Mullican had been a US Navy mapmaker during the war, working from aerial photographs and becoming interested in camouflage.)

One might attempt a typology of Mullican’s work according to the role of screen and abstract background: Sometimes the two elements would balance; sometimes the screen would be missing or semi-transparent; sometimes the screen’s density would obscure the background altogether. A Freudian might see the screen as repression, or it might be the barrier between outer and inner space, the known and the unknown. That such screens might be congenial to Mullican’s thought may be discerned in his remark about a marble head veiled with a cloth he had seen in the Corcoran Gallery —“Seeing reality through, behind, and beyond something important which was pulled down in front of it…I feel that’s the way I operate.” 24

Ultimately such structuralist schematization proves unsatisfactory because the paintings are in fact made of multiple layers. A 1953 observer found Mullican attacking a new vertical canvas with a 2-inch housepainter’s brush, splashing the surface with a mixture of thinned turpentine and a bit of pigment that was allowed to drip. Then came a constellation of brown patches “wheeled around a central vortex” which soon divided themselves into “two rotating swarms.” Then “the centrifugal force of his two rotating swarms was countered by streaking-in strategically placed thin vertical passages, giving to the picture the addition of a feathery, floating sensation.” Then came another turpentine wash mixed with cadmium yellow. Only then was the painter ready to apply striations, some edges of which he softened by lightly spraying with turpentine.25

“The paintings whose transparent quality I admire the most are those of Lee Mullican…. The new art may well take as rallying point—transparency,” Onslow Ford wrote.26 It is not clear whether Onslow Ford was referring to such washes and glazes or something on a more spiritual plane.

The observer found that Mullican was careful to make the initial attack on the canvas in “an uncontaminated frame of mind.” Then came another risk, since

Change is so rapid, the speed of composition so quick, it is difficult to stop the painting from destroying itself, complicating itself beyond treatment. The discipline necessary is often late in arriving for I am prone to let the painting do as it wishes.27

The artist worked on the painting in question for six weeks, allowing as much as a week to elapse between sessions. Sometimes he would “surprise” it while rushing about other business and “add a fragment from this spontaneous ambush” in order to “freshen” it. He tried to maintain a “delicate balance between surprise and contemplation.”28

Lee Mullican, Untitled (from the Raga series), 1962. Oil on canvas, c. 60 x 50 inches. Courtesy of Donna J. Cramer. © Estate of Lee Mullican. Photograph © 2006 Museum Associates/LACMA. Photo: Dan Kramer.

The complexities of this process and the subtle balance between spontaneity and control at every turn in the unending search for the inner space evidently became more important to Mullican than the finished painting, which was “just a record of the process… It’s just a record of my being an artist, and the real vital thing is that I am that artist.”

As I say that I am standing on this particular metaphysical, almost unexplainable plane in my studio, and the canvas is there before me. And it’s in this attitude that makes the painting appear. And once it appears, you just put it aside, and whatever reason, it’s there now, and you’re not quite sure how it got there. If you examine it…You don’t and I’m speaking of myself you don’t want to examine it that much. Just accept it, you see. 29

What has appeared is a painting that has successfully arrived at the inner space. But with a process so out of control, one can never be sure where it will end up. That would explain the so-called unevenness of the work. It might not even take off in the right direction, which would explain the unfinished canvases. If the process were more important than the work, that would explain why Mullican allowed Palmer Gallery to hold his work for years without promoting it while he busied himself making more of it.

One might say that this attitude was supremely selfindulgent and egotistical at the same time that it was totally selfless in sacrificing external recognition for the intensity of a spiritual quest. In contrast to some artists who destroy what they consider to be their second-rate work, Mullican kept everything, so one may appreciate his honesty, his willingness to let it all hang out.

Plagens, trying to determine in 1969 “whether Mullican is a major independent artist,” decided “Mullican is good, very good, but that, in spite of his consistency of application and pervading nature-mysticism, what keeps him from being really significant is unevenness.”30 It was apparently not Mullican’s primary goal to be judged significant.

Plagens also faults him for pursuing a visionary style (“that is to say personal, colorful, mystic, optimistic”) through a conservative technique (that is, “his physical way of making a painting”).31 That contradiction has almost theological dimensions insofar as it relates to the extent to which faith should be guided by reason. Pittman, who would prefer to view Mullican’s work “through a more secular lens…in this revisionist moment,” is clearly more interested in the physical painting than in the artist’s intentions in producing it.

Pittman, who says he has “always responded to [Mullican’s work] very strongly,” recalls that when, as a board member at LACE about twenty years ago, he proposed a Lee Mullican show, the “appreciation of [his] work by a younger generation of artists was quite frankly nonexistent.” Today he finds “the work looks incredibly hip again,” and that young artists respond to it as “a very intense document of subjective experience.” The artist’s seesawing between pure abstraction and imagery, which Clement Greenberg or even Alfred Barr would have seen as “a liability in the struggle, is now purely a contemporary asset.” Pittman, who teaches at UCLA, asserts, “Many times an artist can be revived through the recontextualization of their work with a much younger generation, and so I see a lot of abstract cosmological painting being done.” 32

Several factors have promoted this “reappreciation” of Mullican’s work, according to Pittman. One is the decentralization of Manhattan within a more internationalized art world. Another is an impulse to re-look at American modern art in general, both for historical reasons and “just simply in the pragmatics of mercantile business, because American modern art remains in many ways profoundly undervalued and underpriced.” Still another has to do with “a shift away from mediated imagery and technological interventions [toward] what would loosely be called ‘direct application’… as a way of actually making the painting.”33

At the recent LACMA show of Mullican’s work, I spent some time looking at Pendulum Factor (1953), a classical School of Paris painting worthy to hang beside a Juan Gris or Georges Braque and certainly an early Matta. The painting seemed marvelously unified in terms of space, color, and treatment. Analyzing it, I found it aesthetically gratifying. I tried the phenomenological strategy of “free imaginative variation” wherein one mentally subtracts elements to find which are the essential ones. Subtract the brown objects? They give structure and direction to the painting. Subtract the gray ones? They give it depth and mystery. Subtract the light brown ground above? That closes in the top of the painting and prevents it from feeling too ecstatic and utopian. It seems that all the elements are essential.

In the same show, I saw another painting that appeared to me ungainly: its color garish and its interior full of unfriendly thorns. Between the two, I knew which one I liked but could not be sure which was the “stronger” painting. In Santa Monica, I told this to Luchita Hurtado, who shrugged and said, “One sings and the other one growls, and if you are a growly person you respond to the growls.”34 Art is entirely subjective, she feels.

I asked her if there might be a germ of understanding in Paalen’s comment that “Air is the element for Lee, and all it carries, pollen, feathers, the dreams of birds and spikes of stars, and the holy nest of winds.” Of course, there is a Mullican painting called The Nest of Winds, and perhaps the other terms refer to other paintings.

She hesitated and then replied, “I don’t know if you’ve felt it at all. Lee had a very special persona. He was a very quiet, very silent person. When Lee was in a room, it was like the presence of a cat. You’re aware of it, but it’s not moving at all. There’s something very special around him, and that might have been what Paalen was referring to…”

I think part of the person who paints the painting is in the painting, don’t you think?…When you walked into Lee’s show [at the museum], you felt a special ambiance—it was joy or whatever. At the show that opened at Marc Selwyn’s, the feeling that you got when you walked through the galleries with these big paintings was completely different.35

Mullican seems to have cultivated a chameleon identity in pursuit of his ideals. Although his efforts may at times appear carelessly spendthrift or uneven, at a phenomenological level the work can come across as versatile. And individual pieces can grab you suddenly—like a cat springing through the air.

Michel Oren is currently teaching a course in “Intercultural Art” at CalArts.