One bright March day, a group of friends gather around a table in a piazza in Turin, Italy, exchanging small bouquets of mimosa with fronds rendered electric yellow and foliage that burns green. All across the country, women are making these tender exchanges to mark the Giornata internazionale della donna—an ancient rite in Italy that long predates International Women’s Day. But March 8 is also a day of strikes and political action, and this year is no exception, with travel plans, schooling, and healthcare derailed not just in Italy but across Europe. Beyond the sweet smelling fronds of mimosa is an air of refusal.

Lee Lozano: Strike, installation view, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, Italy, March 7–July 23, 2023. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano.

It was on this day that Pinacoteca Agnelli, in Turin, opened Strike—the first major retrospective in Italy for the American artist Lee Lozano—and, in doing so, acknowledged, if not confronted, Lozano’s complex relationship with the art world, with women, and, we might speculate, with her own identity as a woman. It is a provocation made twofold—both for and against the artist who, on the one hand, railed against the systems that hold us and, on the other, rejected feminism and, later, women from her life altogether. I imagine that Lozano would have enjoyed this perversity, turning with pleasure in the unmarked grave in which she insisted on being buried.

To strike is both a physical gesture and political act, and Lozano brought these things to touch through painting and drawing, text, and, perhaps most importantly, her conceptual works, some of which lasted a lifetime. For Lozano, politics took the form of personal reinvention and transformation, casting aside the expectations of gender but also labor and economics. To strike is also a refusal to take part, and this inaction, not to be confused with inertia, is a pervasive theme throughout Lozano’s work. In 1970, she abandoned the art world entirely, in a conceptual work known as Dropout Piece (1970). A year later, she severed all relations with women—letting the phone ring, ignoring them in the street—in what she called her “boycott of women.”1 Envisaged at first as a temporary action, Lozano extended her opposition to the art world—and to women in general—for the remaining thirty years of her life.

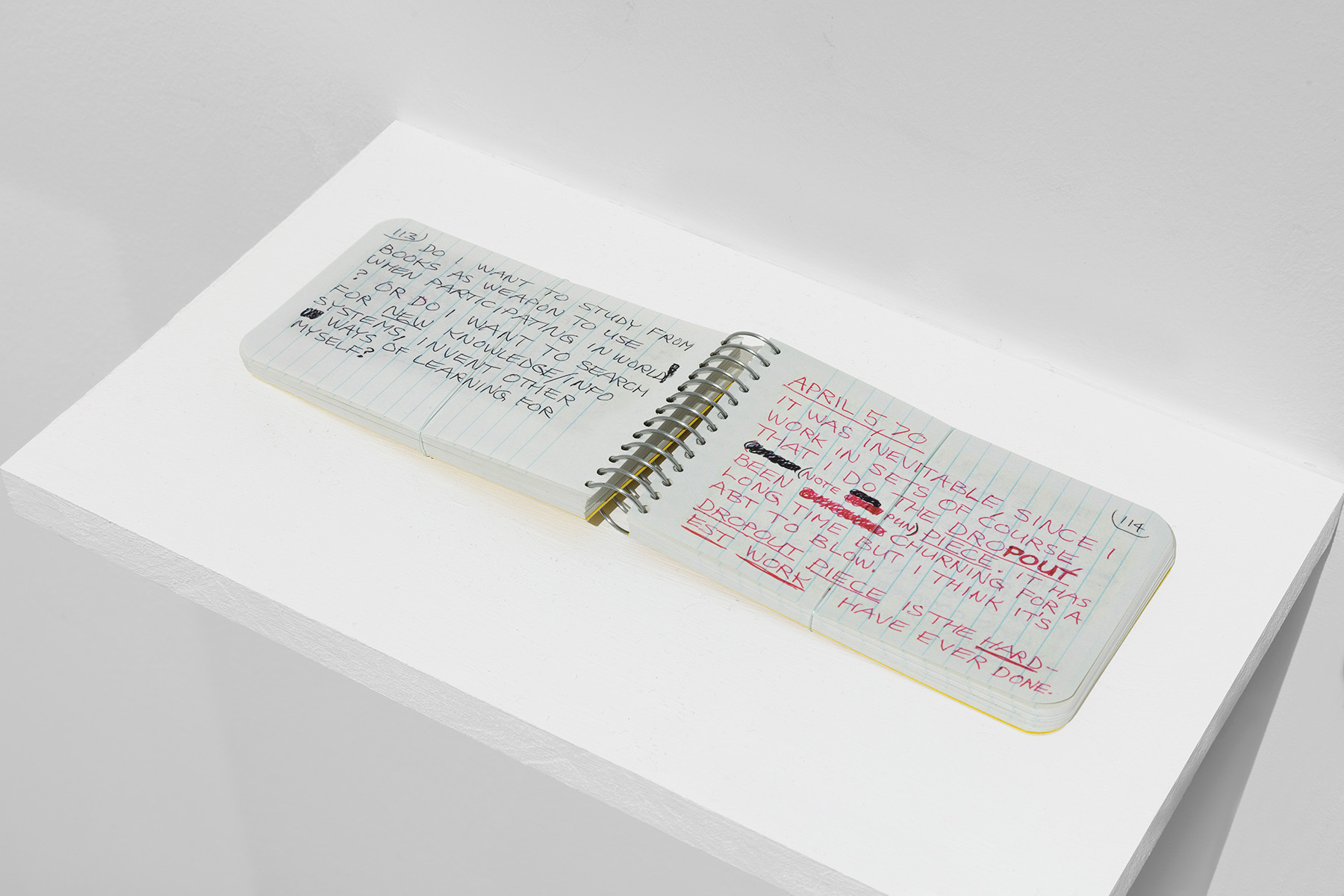

Speculation about the life of Lee Lozano abounds, but it is necessary when dealing with an artist who refused to speak to and about the art world for much of her life. Lozano kept a series of tiny notebooks, called her Private Book project, which were published in 2018 by Karma books as an eleven-volume facsimile.2 Apart from those terse entries, we are reliant on other people’s readings of Lozano’s life—namely a handful of scholars—while trying to avoid putting words into her mouth. “When Lozano dropped out of the art world, her practice ceased as a career and became something else,” writes Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer—author of Lee Lozano: Dropout Piece. “I think her work continued and pieces happened that never made it out of her head [and] onto paper,” she continues.3

Lee Lozano, Notebook 8, 1970. Installation view, Lee Lozano: Strike, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, Italy, March 7–July 23, 2023. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano.

Amidst such speculation, there are at least some facts; let’s call it biography. Lozano was born Lenore, in 1930, in New Jersey. Between 1948 and 1960, she studied at the University of Chicago and subsequently at the Art Institute of Chicago, then travelled around Europe for a year before returning to New York in 1961 and settling in Manhattan. In 1970, she dropped out of the art world and moved to Dallas, Texas, to live with her parents (the only exception to the rule about women was her mother). Lozano died there in 1999, at the age of sixty-eight.

That Lozano’s work—so concerned with mechanisms of labour, of art-making, and of the body—is being exhibited here, in the Lingotto—Turin’s old FIAT factory with its rooftop racetrack made famous by the car chase scenes in The Italian Job—is apt. Lozano’s life and work operate like an assemblage of parts, and the Pinacoteca Agnelli presents over one hundred works in a chronology that also tracks her shifts in style and subjects and her various personal transformations—“sex (1931, continuing), drugs (1959, continuing), art (1935, continuing).”4

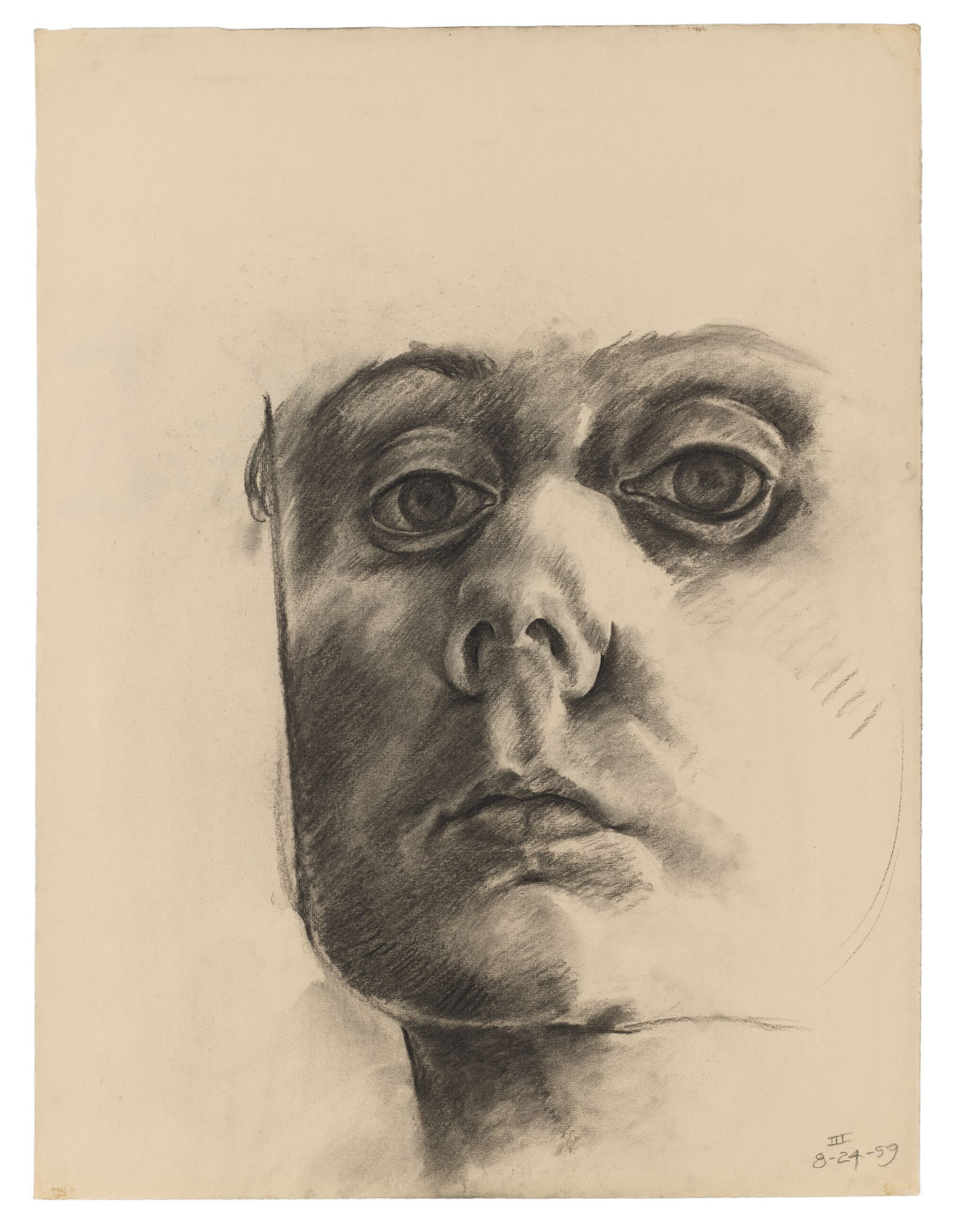

We are confronted first, and on four walls, by Lozano’s early drawings of body parts and mechanical parts, which she made in 1961 and 1962, when she moved back to New York following her studies in Chicago and her travels in Europe. Presented in a confined, windowless room, these works are framed and stacked tightly together, extending far above eye-level and down to the ground. Pictorial—borderline comical—drawings of screws and pencil sharpeners are rendered in crayon, in bulbous, representational forms; other works are stripped back, abstracted to the mere insinuation of an anatomy in the ellipsis of an upturned mouth or the hood of a penis. A single screw fills the frame, produced in tarry metallic pencil that catches and pulls at the light along the ridges and darkens in the grooves. We move through to a series of paintings and a room of hammers raised, glaring silver, in gestural strokes that are charged with the electricity of human intent. Blown up to fill the entire canvas, the quotidian tool enforces a new sense of meaning—of looking.

Lee Lozano: Strike, installation view, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, Italy, March 7–July 23, 2023. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano.

To strike is both physical gesture and political act, but it is also a feeling, and what strikes me first and most about Lozano’s work is the intensity of feeling that she garners through form—muscular, metallic, writhing form rendered in pencil, crayon, and charcoal, and later in acrylic and oil. Sometimes the form is a manufactured tool—pencil sharpener, wrench; other times it is the mechanism of the human body—phallus or breasts. All share a sense of movement, of labor, of function, despite their incoherent physiology of hard and cold and warm and soft.

Lozano received a classical training and education in painting in Chicago; she was taught how to control the medium while simultaneously confronted with the conceptual leanings of the likes of Claes Oldenburg. There are traces of the School of Paris—Chaïm Soutine and Pierre Bonnard, a cubist construction of composition and thinking through color. I also see a Mannerist darkness in Lozano’s paintings and her base palette of muted browns and steely greys, although she rarely uses anything as officious as black. When she returned to New York in 1961, she entered into a moment in the artworld that Randy Kennedy describes as “a brief lacuna at the end of abstract expressionism’s reign,” manifesting for Lozano in her gestural strokes and her “flowering” of figurative painting, “before pop and minimalism became the dominant language.”5

Lozano’s impetus to move forward but also regardless of such movements explains some of her grievances with second-wave feminism. She famously declared herself “not a feminist” because it effectively tried to distinguish women’s experiences from men’s and in doing so veered dangerously close to producing another universalizing factor.6 In some sense, Lozano anticipated, and stood clear of, the trappings of a so-called feminist art—one that reclaimed domestic space, decorative traditions, textiles, and sometimes motherhood (in the vein of Judy Chicago, Faith Wilding, and the A.I.R. gallery artists)—and the perils of essentializing gender. She wasn’t interested in the clean line of minimalism or the muchness of post-minimalism. Apart from a few painters that she obsessed over, such as Agnes Martin, Brice Marden, and Kes Zapkus, Lozano rarely aligned herself with others. Her reluctance to be defined or contained extended to her personal identity. She changed her name from Lenore to Lee and eventually to simply E, suggesting her reluctance to be named or defined but also to define. A list of her works reads: No title (1962), No title (1961), No title (1963)…

Lee Lozano, No title, c. 1962. Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 in. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth and Private Collection.

“I HAVE NO IDENTITY,” Lozano wrote in 1971, “I HAVE AN APPROXIMATE MATHEMATICAL IDENTITY (BIRTHCHART).” And later: “I WILL GIVE UP MY SEARCH FOR IDENTITY AS A DEAD-END INVESTIGATION.”7 Her refusal to identify, period, is a radical gesture; but still I struggle to reconcile this impetus with her decision to boycott women—a position that risked huge fallout and broader social reverberations amongst and between women while permitting her to enter the dominant culture of the New York art world—one of alpha males like Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris. Early on in her private notebooks, she rationalized her decision as “IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATION OF TOTAL PERSONAL & PUBLIC REVOLUTION” and later, “AFTER THAT COMMUNICATION WILL BE BETTER THAN EVER.”8 Revolution is finite, a brink in time, and it is that temporality that causes the greatest commotion. But the future conditional in Lozano’s proposition eventually became obsolete, and her decision to withdraw was final. Later that year, Lozano wrote, “WHERE COMPETITION THRIVES, FRIENDS CAN’T EXIST.”9

Lozano’s outlook seems bleak, but perhaps necessary while seeking to emancipate herself from the confines of gender, period. “I THINK BOTH MEN AND WOMEN ARE SLAVES IN TODAY’S SOCIETY,” she wrote in her notebook in 1971.10

Lozano worked to undo the complex and contradictory expectations of gender, and this resistance is felt explicitly in the way that she mechanizes the body. Lozano makes light work and humor of the body—its joys and ejaculations, its perceived failures, flaws, and discrepancies. But she also evokes bad advertising and the mechanization of bodies as consumer goods—fetishized, pawed over, and abhorred in equal measure, turning them into something utterly profane. Her Hygiene, Body Box, and Subway series (all three c. 1962–63) present drawings of autonomous cocks and tits accompanied by bubble writing that imparts one-liners. In 0.7 No title (1962), the words “he gave her a good screwing, he said” are illustrated brilliantly and obliquely by the writhing action of a sharp-toothed saw. Lozano’s “bad” gags and one-liners mimic the comic who deeply craves applause, reminding us, unsettlingly, of the basic human need to be validated—something that Lozano would later rail against in her Dropout Piece. Lozano’s greatest strength is confronting us with these human realities—she gives us the tools and makes us do the work. These works are not beyond or over gender but complicate it, namely by using the body and thinking of it as “an elaborate container.”11 She conceived of a game called Sex State, in which two people or a group—regardless of gender—could “experimentally redesign themselves to fit together in new ways, depending on chosen shape.”12

The staging of Strike within the Lingotto feels fitting for an artist interested in the conversation between gender and labor—between who performs them and how they are performed. Lozano’s cocks and tits are closer to armature or weapons—erect, firing on all sides—than body parts. Before it became the world-famous factory for FIAT cars, the Lingotto was known as La Lingotta and manufactured household appliances. The factory and the appliances were largely operated by women; they were paid to make the machines that would emancipate them from unpaid and domestic labour, so the advertisements said. But the rollout of domestic appliances also meant the end to communal washing and cooking duties among women now confined at home. And it is the same ruthlessness of capitalism, along with the domestic expectations of the patriarchy, that Lozano rails against in her conceptual Dropout Piece and broader principles for living—principles that rejected nuclear families in favor of independent personal transformation.

Lee Lozano, No title, 1962. Installation view, Lee Lozano: Strike, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, Italy, March 7–July 23, 2023. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano.

Lozano’s work is at its best when it imparts the mechanisms and labor of everyday life—blurring distinctions between body and machine. Most affecting are the paintings of bodies that intuit machines rather than transform into them entirely. One voluptuous, near fleshy pencil sharpener is imagined not merely as a prop but also as the tool that facilitated its very line and shadow. A series of paintings from 1962 elucidates the airplane, making it lighter and less constrained by representation and sometimes abstracting it into soft, inconceivable corners and scaling it down to interact with the cleft of an ear or the orifice of a mouth. Like Lozano, the plane moves toward and away from the body, with imprecision, and cartwheels in the sky, bumps, and grinds. In her private book from 1968, Lozano wrote, “CURE FOR GLOOM, crankiness, blues, etc. Have a disembodied paper aeroplane flying around all the time.”13 Elsewhere, a woman’s body is rendered in soft brushstrokes, punctuated with a metallic slot at the vulva and a hand reaching to insert a dime. This latter work, like Lozano’s rendering of butter melting delectably on a plate spliced by the sharp side of a metallic knife, conflates tenderness with violence and resonates with her statements, such as “AS LONG AS WE CONTINUE TO BE IMPRISONED IN OUR OWN BODIES, THE OBJECT WILL NEVER DIE. TOO BAD.”14

The entire show is galvanized in Lozano’s bold, sometimes verbose style, which does not balk at preconceptions about what “masculine” and “feminine” art might look like but rather blows them up and to pieces. Jo Applin suggests that, in rendering rather than “instrumentalizing” hardware tools, Lozano is also making a “sly commentary” on the working process of people like Serra and LeWitt.15

Amidst the greys and turgid browns of mechanical parts and cocks is a lipsticked mouth in the blood red of iconoclasm and seduction—one made typically feminine. A reoccurring motif in Lozano’s work, these lips part to expose teeth that are too clearly defined, turning this uncannily dismembered mouth into a petulant rather than erotic statement and a grimace rendered at one point on the back of a toilet lid.

Lee Lozano, No title, 1962-63. Installation view, Lee Lozano: Strike, Pinacoteca Agnelli, Turin, Italy, March 7–July 23, 2023. Courtesy of the Pinault Collection. Photo: Sebastiano Pellion di Persano.

In 1966, Lozano presented a series of abstract-geometric paintings at New York’s Bianchini Gallery, with titles such as Lean, Slide, and Clash (all three works, 1966). This time, Lozano turns to the tubes and the piping that are spliced and hammered by the tools in her earlier paintings and renders them in soft brushstrokes that scale across several large canvases, which are split but touching. A room of these works at the Pinacoteca becomes a marked break in the screwy and figurative series that precede and follow these canvases, stopping to acknowledge the sexual and sensorial revolutions Lozano was undertaking at the time, through lovers and drugs. “ART DOES NOT NEED TO BE MONUMENTAL, BUT MOVEMENT (CHANGE) DOES,” she wrote, in an early private book.16 In these large-scale canvases, Lozano loses sight of a formal object, or perhaps gives form to the abstraction of her ideas around gender. The works mark her retraction—perhaps even purification—of her identity toward the essential Lee, which would one day be simply E.

In a brilliant piece about Lozano for Frieze, simply titled “On E,” Bruce Hainley quotes Lozano saying that the “biggest line of all is always that transition between the second and third dimension,”17 and I sense that this train of thought extended to gender, positing a third term, a something other that refuses the binarism of gender. By rejecting feminism and exposing the functions and failures of human and nonhuman anatomies, male and female alike, Lozano suggests—with much foresight—that she is not on anyone’s side. As a writer and a feminist—and a product of society—I am discomforted by Lozano’s refusal to take sides (or belong to any one community). This response reveals—with the force of a strike—my own limitations around how and on what terms, or within what categories, we are expected not only to make art, but also to live in the world.

Lee Lozano, No title, 1959. Charcoal on paper, 25 x 19 in. © The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth and Private Collection. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich.

By performing an example of refusal, Lozano teaches us that not doing something, or the thing, can be far more radical than doing it. This reticence toward familiar gender definitions, feminisms and the economics of the art world will antagonize viewers informed by, if not conforming to, western ideologies of achievement, completion, and success. And in this sense, to engage with Lozano’s work feels like a provocation, a set up: she doesn’t care if we agree with her ideas or like the work; she might even prefer it if we didn’t.

In her very first Private Book from 1968, Lozano writes: “ALWAYS HAVE AN ARGUMENT WITH A FRIEND WHO KNOWS THE RATING SYSTEM ABOUT WHICH CATEGORIES THE ART IN QUESTION FITS.”18 In these consistently CAPITALIZED entries, in which she shares her disdain for things like the moon, as well as people and sometimes form, and in her boycotting of women, Lozano struck back by striking. She did refusal but also gives us ground for it—sometimes we feel it toward her work, and sometimes we are right there in it with her. She permits us to feel unsettled; she gets right under the skin, down to the nuts and bolts of us.

Rose Higham-Stainton is a writer, critic, and teacher whose work is held in the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths College and published by the likes of Artforum, Texte zur Kunst, LA Review of Books, Apollo, The White Review, Art Monthly, Bricks from the Kiln, MAP Magazine, and Worms. Her book Limn the Distance about decentralization and feminist praxis is out now with the interdisciplinary publisher JOAN.