Let me begin with a brief personal anecdote. When I first read Learning from Las Vegas, about a year after it was published in 1972,1 I was an undergraduate art history major for whom architectural history meant poring over the magisterial work of Alberti and Palladio, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. It didn’t mean hanging out at Caesars Palace or along Fremont Street, advocating for “decorated sheds” or teasing out the communicative strategies behind the “Tanya” billboard. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour changed all that. By legitimating for me the act of “[l]earning from the existing landscape,”2 by which Venturi and Scott Brown meant the commercial vernacular of the suburban strip as exemplified for them by “The” paradigmatic Las Vegas Strip, they seemed to open the world of academic discourse onto the world of my immediate and lived experience. For a lower middle class kid struggling to find an intellectual place at a fancy Ivy League university, this was definitely a very big deal. It was like running a two-lane blacktop from my hyper-Levittown suburban housing development in northern Virginia, with its identical little brick tract homes and its burgeoning tacky strip malls, all the way across the Atlantic Ocean and right up to the driveway of Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, the apotheosis of the modernist house as “a machine for living in.”

As it turns out, Learning from Las Vegas was a big deal for a lot of other students of the built environment as well. The book has been celebrated and derided, among other things, as one of the foundational documents of Postmodernism, as a gentle if insistent cri de coeur for a new populist architecture, and as a vindication of the “degraded” landscape (unjustly) stigmatized by Peter Blake in his brilliant 1964 polemic God’s Own Junkyard.3

Installation view of Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown at the Moca Pacific Design Center, March 21–June 20, 2010. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Now, as the fortieth anniversary of its initial publication looms on the horizon, that celebration has been formalized in a beautifully mounted traveling show recently on view at MOCA’s Pacific Design Center Gallery, Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, and accompanied by a equally handsome publication under the same title, edited by exhibition curators Hilar Stadler and Martino Stierli in collaboration with Peter Fischli.4

The show itself, which was comprised virtually in its entirety of artifacts drawn from the Venturi and Scott Brown Archives, used a variety of media–walls of photos and supergraphic charts reproduced in the original book, an endlessly repeating slide presentation, and four films–to create something of the experience of the 1968 Yale University research studio whose work formed the backbone of the analysis eventually embodied in Learning from Las Vegas, as well as the excitement of the initial public presentation of their research, which took place at the Yale School of Architecture on January 10, 1969. Indeed, the slides, films, and supergraphics in the MOCA PDC show were all employed at that presentation, which had generated sufficient pre-event buzz to draw the attention of such luminaries as the Yale art historian Vincent Scully (an early and staunch Venturi advocate), the architect Morris Lapidus (whose designs include the flamboyant Fontainebleau Hotel on Miami Beach), and the writer Tom Wolfe. Not bad for a class project, although the critical reaction drawn by the students and their mentors was decidedly mixed.5

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas, 1966. © Venturi, Scott Brown And Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

Although small in absolute size, Las Vegas Studio fit nicely into the second-floor exhibition space at MOCA PDC. It provided an experience that could be hot and cool, intense and reflective, engaged and “deadpan,” to borrow an adjective appropriated by the Venturi and Scott Brown studio from the chatter surrounding the contemporary work of Edward Ruscha. Ruscha’s concertina foldout photo series Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1965) suggests a key element of the studio’s own working methodology.6 After about an hour alone here, much of it spent watching and rewatching extended sequences of slides and the studio’s quartet of films, I began to feel a palpable sense of excitement. Partly, I’m sure, this must have been a resurgence of my own initial excitement at reading the book, and of being swept up in the power of its visual presentation (sumptuously designed by Muriel Cooper at MIT Press).7 But I’m sure it also reflected a sense of the excitement that Venturi and Scott Brown’s students must have felt at participating in what had to have been, if not the conscious birth of something called “post-modernism,” one hell of an amazing field trip.

What the immediate experience of the installation did not provide was much of a sense of context, either historical or architectural. That was supplied rather by the accompanying publication, which framed a sizable selection of evocative and informative (and often pictorially stunning) archival images with three critical and reflective texts: “Las Vegas Studio,” by Martino Stierli; a conversation between Stierli, Rem Koolhaas, and Hans Ulrich Obrist entitled “Flaneurs in Automobiles” (I found Koolhaas’s critical and historical comments here especially cogent and insightful); and a brief but incisive essay, “Tableaux,” by Stanislaus von Moos. All three of these texts raise issues of considerable importance as regards the hotly contested questions surrounding the identification and taxonomy of various architectural postmodernisms, and their relation to the theory and practice of the Venturi Scott Brown studio, beginning even prior to the publication of Learning from Las Vegas.

The image of Las Vegas evoked by Venturi and Scott Brown, has by now itself become an object of historical analysis, “archaeological” reconstruction, or (for the gamblers among us) perhaps even of nostalgia. Although the kinesthetic experience of the Strip that they describe was brilliantly re-constructed through a clever interpenetration of text and image, both in the first edition of the book and in the recent show, it is, to a large extent, already a journey through a ghost town, inhabited by the likes of Andy Williams, Flip Wilson, the Lennon Sisters, and “Mr. Dull Guy” Jackie Vernon.8 Three of the iconic hotels at the heart of the analysis are themselves no more: the Stardust, which closed in November 2006 and was imploded in March 2007;9the Dunes, likewise imploded and replaced by the Bellagio; and the Aladdin, now Planet Hollywood. Indeed, so much of the Strip has been reconstructed, reconfigured, and explosively expanded that its iconic representations today are more likely the Luxor and New York, New York rather than the Riviera or the Tropicana. Of the architectural “old guard” celebrated by Venturi and Scott Brown, only Caesars Palace has both grown in size and retained its presence–as perhaps befits its self-aggrandizing imperial theme. (Compare, for example, the Aladdin, whose 1001 Nights theme was evanescent and inherently transient by contrast, and whose delicate evocation of Scheherazade has been replaced by the aggressiveness of contemporary Holly-world.10)

As if to finally seal the fate of Venturi and Scott Brown’s shimmering desert mirage, the equally iconic “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign (designed by Betty Whitehead Willis and installed in 1959) was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on its 50th anniversary in 2009, and described by the National Park Service in its check-box characterization as a “property…associated with events that have made a significant contribution to broad patterns of our history.”11 Its architectural classification is given as “Exaggerated Modern/Googie,”12 what we might term now as something like “retro-futuristic.” It’s easy to imagine George and Jane Jetson zooming past with Elroy, Judy, and dog in tow, out for a family vacation in the Southwest’s desert entertainment mecca.

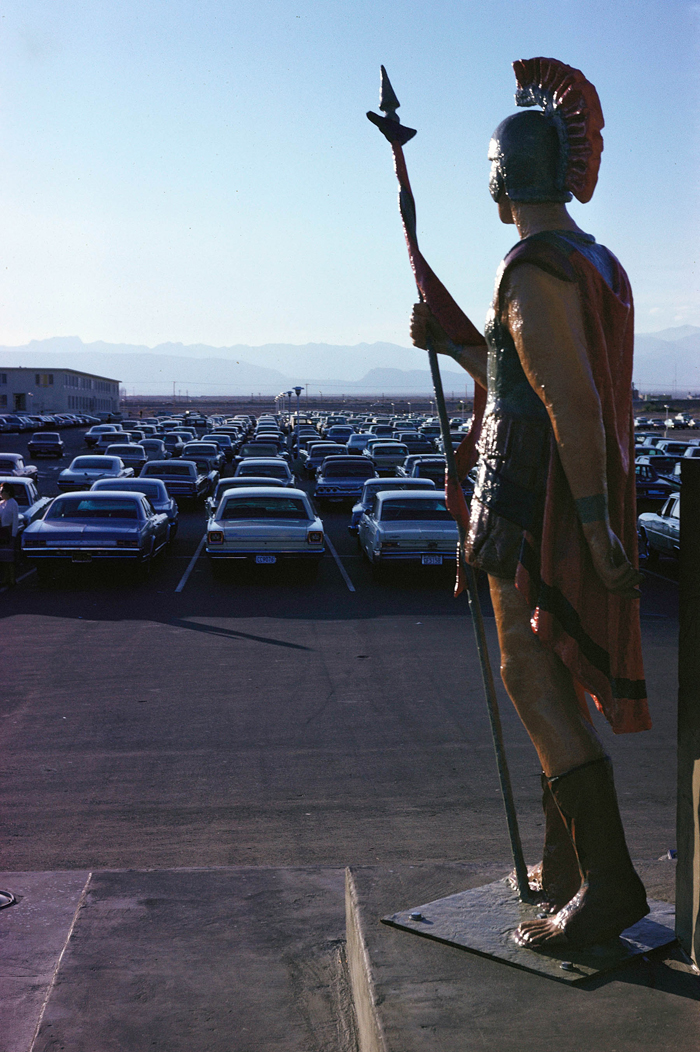

Roman soldier, Caesars Palace Hotel and Casino, Las Vegas, 1968. © Venturi, Scott Brown And Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

Almost needless to say, the city has metastasized. With a metro area population approaching 2,000,000, it is one of the fastestgrowing metropolitan agglomerations in the United States. The path of a contemporary automotive “flaneur” is no longer Las Vegas Boulevard (the Strip itself), let alone the oncepedestrian friendly Fremont Street running into downtown from the site of the old railroad station; it is rather I-15, whose elevated speed limit (assuming the traffic is moving more-orless at speed) is now matched by the scale and presence of the architecture, and along which a continuous procession of billboards is now articulated to engage the interest of passing motorists. As the park service describes:

” When the ‘Welcome’ sign was built in 1959, the closest hotel-casino was the Hacienda [1956-1996], which was a one-story rambling building on the site of the current Mandalay Bay Hotel and Casino. There was no Interstate 15 until the early 1970s and traffic from Los Angeles traveled along the Las Vegas Strip, which was then U.S. Highway 91.”13

Meanwhile, the architecture has evolved as well. The old-style “decorated sheds” with their flashily individualized facades subordinated to massive signage dominated by slick interplays of text and symbol have been increasingly marginalized and replaced by anonymous towers glowing golden in the sunlight, or theme park derived mini-megastructural “ducks” that can whisk us off in an instant to a faux Egypt, New York, or Paris.

The term “duck,” coined by Venturi himself in response to an image in Peter Blake’s Junkyard,14refers to a building that symbolizes its meaning (whether real or projected) in and through its own structure and appearance. Ultimately, Venturi sees such buildings as heroic and personal gestures, whether mini- or mega- in scale. A “decorated shed,” by way of contrast, is architecturally anonymous and impersonal, its form answering to simple structural constraints (in the Nevada desert, low ceilings to save money on air conditioning, for example) while its identity is established through decorative and symbolic add-ons. The magnificent old sign of the Flamingo Hotel and Casino (which appears in a number of exquisite exhibition photos reproduced as well in the catalog) was a perfect example.15

Although the vocabulary he employs is somewhat different, Koolhaas makes a similar point: “Venturi and Scott Brown discovered the lightness of Las Vegas and how architectural could be provisional. But in the meantime, this has become the heaviest, ugliest, harshest city in the world… Las Vegas as it is now is the opposite of the theories that they extracted from it.”16

Las Vegas Strip, 1966. © Venturi, Scott Brown And Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

Thus, the lessons to be learned from Learning from Las Vegas are now available only retrospectively, as history, or perhaps glimpsed sidelong at seventy miles per hour as the ghostly image of the skeletal framework within what has become a monstrous and transmogrified exterior. Likewise, the book itself has become embedded in the ongoing discourse surrounding Postmodernism, holding an ambiguous place within all the complexities and contradictions (to borrow one of Venturi’s own favorite critical phrases) inherent in that discourse.

What everybody can more or less agree on is: “What was at stake was thus not the city as it ought to be, but rather the city as it actually was.”17 What marked that position out as “post-modern,” at least in some sense, was its clearly stated opposition to the kind of idealized, moralizing, liberal-Utopian planning that was held to have shaped the city of high Modernism, for example in the theory, if not always in the practice, of Le Corbusier.

There are, however, at least a couple of problems inherent in this position. The first involves the notion of what in fact constituted “the city as it actually was.” Venturi and Scott Brown argue that “Las Vegas is analyzed here [i.e., in Learning from Las Vegas] only as a phenomenon of architectural communication,” irrespective of “[t]he morality of commercial advertising, gambling interests, or the competitive instinct.”18 Perhaps that is so, but such a disclaimer was hardly adequate to insulate their work from criticism arising from the ideological left. The redoubtable Frederic Jameson, for example, for whom Postmodernism itself constitutes “the cultural logic of late capitalism,” was fundamentally unimpressed by Venturi’s position. For him, it comprised at best “a kind of [ideologically suspect] aesthetic populism,” and at worst a more or less empty “populist rhetoric” that effectively, if unintentionally, valorized the hollow cultural productions of late industrial capitalism.19

Scott Brown was especially vociferous in rebutting this kind of attack, albeit often with (to my mind) the rather weak assertion that the Las Vegas analysis is keyed to “a sensitivity for marginalized subcultures and respect for their aesthetic preferences.” However, the issue of Postmodernism’s ideological status is not likely to be resolved any time soon, especially as, since the halcyon days of Learning from Las Vegas, the “fate” of Posmodernism has become increasingly entwined with that of globalization.

Fremont Street, Las Vegas, 1968. © Venturi, Scott Brown And Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

At the same time, the structure of global culture in general has become so complex that Jameson himself begins the conclusion of his encyclopedic Postmodernism by posing his own conundrum: the feeling among many of his critics that “having ‘become’ a postmodernist I must have ceased to be a Marxist in any meaningful…sense.”20 All of which makes the polemic around Venturi and Scott Brown’s analysis appear a little naive in retrospect– which in this context is only to say that it has become a fundamentally historical issue.

Needless to say, however, Venturi and Scott Brown’s attempt to understand Las Vegas as a concatenation of particular communicative structures did not seem to everyone to be freighted with the kind of ideological baggage inherent in Jameson’s Marxist account. Rather, issue might be taken with the observational strategy by means of which the actuality of the city and its structures were to be recorded. Piggybacking on Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Scott Brown referred to the strategy as “deadpanning,” the achievement of a supposedly objective representation of the city through what I might have described in 1972 as maintaining a “hiply ironic distance.”21 Yet the final representation of the city produced by Venturi, Scott Brown, and the members of the research studio was in fact hardly superficial in the irony of its construction of a carefully modulated distance from its subject. Dense yet pellucid, nuanced and subtle in its complexity, it was a documentary itself structured by a sophisticated “rhetoric of objectivity,” where frankly “creative interventions,” to quote Stierli’s critique in Las Vegas Studio, were employed to focus and articulate the analysis. “It goes without saying that this attitude represents a highly artificial artistic position.”22

Indeed, Stierli’s comments here are right on the money, at least as far as they go. Yet it might be possible to read the representational strategy in a rather different way: that the already feigned objectivity of Ruscha’s Every Building On the Sunset Strip was appropriated by the seminar and redeployed as if it were a genuine anthropological, sociological, or city planning strategy, where, as along the Vegas Strip, the subject matter under examination has no claimed inherent interest. It’s as if to say, almost certainly with tongue in cheek, “We’re only attracted to Las Vegas as a set of functional and iconological relations in kinesthetic space.”23 This attitude generates a tension–the possibility for crafting or, apparently, eschewing, “artistic interventions” in the act of framing the visual field to be recorded, something of which we can be sure the studio participants were well aware.

Thus, some of the photos in the exhibition appear flat, without affect, slightly overexposed in the brilliant desert sunshine; others are beautifully framed as formal exercises in their own right: naive tourist snapshots on the one hand, artful architecture school photos on the other. One can see the same radical dichotomy in the films: compare Las Vegas Deadpan with the much more artificial and “avant-garde” Las Vegas Electric. And I have seen exactly the same phenomenon in my own Las Vegas photo work as an automotive “flaneur” on the I-15.

Although Venturi himself claimed the strategy of “deadpanning” as a “poetic [device] of long standing,”24 he must also have been aware that the strategy was imbued almost by definition with a kind of iconoclastic humor. We see this, for example in the “comparative analysis of ‘billboards’ in space,” where artifacts as disparate as Amiens Cathedral, a Roman triumphal arch, an Egyptian pylon, a highway billboard (the ever-present Tanya), and the Stardust Casino are analyzed with respect to “scale,” “speed” [pedestrian as opposed to automotive], and the relative weight of symbolic form vs. symbolic signage.25

So what exactly can we still learn from Learning from Las Vegas? That “Billboards are almost all right.”26 Or, more seriously, that “There is a perversity in the learning process: We look backward at history and tradition to go forward; we can look downward to go upward. And withholding judgment [in the last analysis, this is what constitutes ‘deadpanning’ for Venturi and Scott Brown] may be used as a tool to make later judgments more sensitive. There is a way of learning from everything.”27

Glenn Harcourt, intersection of I-15 and Desert Inn Road, Wynn Hotel and Casino, Las Vegas, August 2009.

If nothing else, we can see these programmatic statements, demonstrated with consummate skill in Learning from Las Vegas, elaborated and refined in the immense body of work produced over several decades by the firm of Robert Venturi Denise Scott Brown and Associates.28And it is also in this work that we can see how Venturi and Scott Brown have mapped out for themselves a distinct architectural Postmodernism. Espousing neither the Blade Runner-esque enclosed and reflective counter-city of John Portman’s Westin Bonaventure Hotel that Jameson takes as paradigmatic of late capitalism’s architectural logic, nor (usually) that of the Greco-Disney eclecticism of Michael Graves’s Disney Studio building in Burbank, nor the gestural heroics of Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall,29they have developed a kind of easy-going neo-mannerism, which often shows an enormous sensitivity to the potential of subtle, as well as graphic, decoration, and increasingly complex systems of fenestration –all of which is already present in nuce, in the early project for the Guild House, a high-rise apartment development for the elderly, built in New Haven in the mid-1960s.30 For an exquisite local example, see the Gonda (Goldschmied) Neuroscience and Genetics Research Center at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) (1993-98), which is to my mind a design at once restrained and exuberant, an elegant and powerful anchor at the base of the biomedical section of the Westwood campus.31

Stardust Hotel And Casino. Las Vegas, 1968. © Venturi, Scott Brown And Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

In some ways, works like the Gonda (Goldschmied) Center are a long way from Las Vegas. Yet in another, important way, perhaps they are not so far. In approaching both the UCLA commission and the Las Vegas research studio project, Venturi and Scott Brown have consciously embraced that “perversity” of looking backward into history to go forward into the future, of looking downward at the commercial vernacular to go upward into the studio. In essence, they have striven to embody in their work the enormously sympathetic historical understanding of artistic tradition that Venturi himself celebrated in his 1966 manifesto Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.32 And as such their approach is perfectly figured by a pair of photographs drawn from the Venturi and Scott Brown Archives.

Both photos are taken from roughly the same spot: a patch of sagebrush desert marked by the lone stone chimney of a long abandoned and destroyed house. The view is back toward the Strip in the distance. The Strip itself mostly appears as a white excrescence, a man-made film or crust spreading across the surface of the land; but at significant points, the Las Vegas “miracle” has already begun to rise up: the compact mass of Caesars Palace (which appears in only one of the photos) on the left, and on the right (dominating the Strip-scape) the Dunes with its hotel tower, its futuristic entrance, its iconic sign. Each photo is also marked by a single human presence, offset to the right and standing deep in the foreground. In one photo, the presence is that of Denise Scott Brown. Facing the camera, dressed casually in black skirt, long-sleeved navy top and low-heeled pumps, she stands rather brashly with feet apart and hands on hips. An intense and focused expression confronts the photographer/spectator, as if to say, “Here is the lesson, the apotheosis of the ugly and ordinary in American culture. Take from it what you can or will; but do not deride either its vivacity, or the simultaneous authenticity and fantasy of the self-representation it projects.”

The other photo is rather different in its affect. Here we see Venturi, standing in the desert and facing away from us, toward the Strip. Dressed in a conservative business suit, hands hanging at his sides, anonymous in his literal effacement, he has been compared to Magritte’s famous man in a suit and bowler carrying an umbrella. Yet in at least one important respect he strikes me as quite different. As incongruous as his presence might seem, as he stands alone in the middle of the desert, it also seems clear that he himself is not aware of, or even, as in the Magritte, indifferent to that incongruity. Rather he seems to stare at the city with what I would like to imagine is a look of wistful intensity. For he sees it both in its “deadpan” factuality and in its relationship to that tradition from which and through which we can again move–to quote the arch-modernist Le Corbusier, “vers une architecture”–towards a (new and vibrant) architecture.33Or, to quote Venturi himself in conclusion, an architecture founded on the realization that, contra Mies’s (in)famous dictum, “More is not less.”34

The strip seen from the desert, with Denise Scott Brown in the foreground, 1966. Photo: Robert Venturi © Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

The strip seen from the desert, with Robert Venturi’s silhouette, 1966. Photo: Robert Venturi © Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., Philadelphia.

Glenn Harcourt received a Ph.D. in the History of Art from the University of California, Berkeley. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles.