Larry Johnson, Untitled (Admit Nothing), 1994. Color photograph, 46 x 58 3/4 in. framed. Edition of 3. Collection of Edward Isreal. © Larry Johnson.

Larry Johnson is often considered an artist’s artist. Although colleagues such as Pae White and Nate Lowman reference Johnson’s work, he has yet to attain wide institutional acknowledgement. The exhibition at the Hammer Museum, which features over 60 works from 1982 to the present, is a first step in this direction. The thought-provoking exhibition is well timed, especially considering the subject matter in Johnson’s work— “death, celebrity, class, camp, lust, nostalgia, and obsolescence,” as curator Russell Ferguson writes in the catalog that accompanies this exhibit.1 We just bore witness to one of celebrity culture’s epiphanies, following the death of the “King of Pop” Michael Jackson. While this coincidence of timing clearly was not planned, Johnson’s show also fits a trend of reconsidering contemporary art and the notion of referentiality.2 His place within contemporary art and specific interests in mass culture are also comparable to Andy Warhol and the discourse surrounding the Pictures Generation.

Johnson’s art is highly formalized. Although he almost always uses photography, he does not consider himself a photographer.3 He follows a tradition of conceptual photography in which artists use photography for purposes other than capturing a decisive moment.4 Johnson works with text and images in various combinations invoking the parallel worlds of design and American popular culture.

The exhibit begins with an exception, Paul Rand’s Women, 1948 (1984). It is the only video in the show, but many of Johnson’s interests are on display. The piece refers to the cover of an exhibition catalogue designed by Paul Rand in 1948, in which the letters W-o-M-E-n are placed loosely over the entire cover. In Johnson’s video the letters are floating gently across the screen, forming words such as ME, MEn, oMEn, WoMEn. Various arrangements of the letters playfully generate different words and meanings that we start to connect with each other. Even though it is an a-typical work, it wonderfully introduces Johnson’s subject matter of typography, word play, referentiality, and gender. Looking at his whole oeuvre, Johnson also references Modern Art, cartoons, the urban look of Los Angeles, gay culture, and “camp”–“Dandyism in the age of mass culture,” according to Susan Sontag.5 The oft-debated notion of camp is hard to pin down, but a common denominator is an understanding of camp as style and behavior that refer to distinguishable styles of the past, exaggerated and combined in the present. Ferguson highlights another component: “one of the key techniques of camp is to recuperate elements of the outmoded…and turn them into revalorized signifiers”–a technique that can be recognized in Paul Rand’s Women, 1948.6

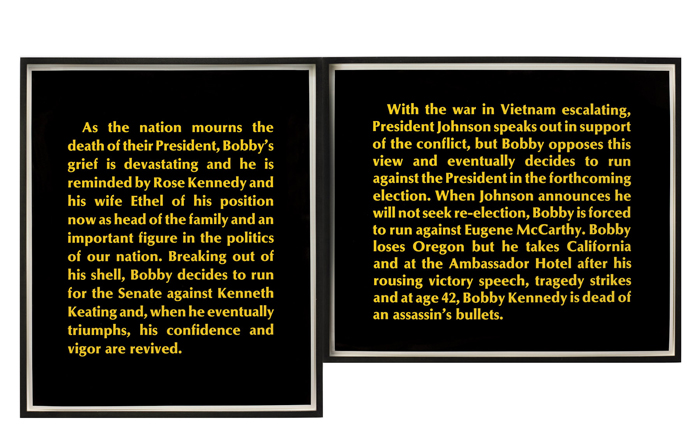

Larry Johnson, Untitled (Grief Is Devastating), 1985. Color photographs. Two panels: 25 1/2 x 21 1/2 in., left; 21 1/2 x 25 1/2 in., right. Edition of three. Collection of Judy and Stuart Spence, Los Angeles. © Larry Johnson.

Another significant part of Johnson’s work is related to celebrity culture. Untitled (Grief Is Devastating) (1985) is a pair of color photographs featuring yellow typography that pops out against a black background, suggesting illuminated letters. The text panels inform us in rather factual language of the deaths of the two Kennedy brothers, John and Bobby. Starting with the mourning of JFK and ending with the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, the work leaves us with a double grief. We mourn for both Kennedys as well as for the lost “love and peace” era that was terminated by assassinations in the 1960s. In fact, the Kennedy clan has repeatedly been a subject matter for Johnson. We find more sexually suggestive references in the diptych Untitled (John-John and Bobby) (1988). Whereas the left text panel starts with the Kennedys, on the right panel they transform into fictional characters who take part in a gay porn film shoot. Johnson gravitates to the Kennedys as subject matter because “they’re a stable of characters, they’re stock.”7 His fascination with this family also fits into Johnson’s more general interest in celebrities. He says that celebrities are “great motifs because you don’t have to do any background for the reader. It’s kind of shorthand. I don’t have to describe anyone for my readers; the language is just as familiar as any character.”8

Johnson takes advantage of the ready-made narratives of celebrity culture, narratives that travel in their most condensed form through text. He is interested in certain types of narratives and their functions: “What I focus on are the precepts that accompany… emotion: the confession, the self-explanation, the release, the testimonial, the testimony. The things that have come to signify what is meaningful.”9 In contrast to Johnson’s fascination with stories, his predecessor Andy Warhol highlights the iconic quality of celebrity culture. Warhol not only focuses on faces, such as in Celebrity Portraits or Screen Tests, but his work employs the visual effect of imagery to a point of super-saturation. Compared to Warhol’s visual practice, Johnson–in Duchampian terms–strips the celebrity culture bare from its images and focuses on language as reference. He seems to mistrust the visual effect of the star industry. Also, Johnson doesn’t embrace such a wide array of celebrities as Warhol, but links his choice to his own life and interests. Art critic David Pagel has addressed the comparison of Warhol and Johnson by writing, “whereas Warhol’s fixation on external details overwhelms the possibility of any attention to the painful complexities of subjectivity, Johnson’s narrative suggests a potentially poignant tension between an inner life and the outer signs that too often deficiently signify its experiences.”10

Even though Johnson’s work cannot be read as autobiographical, it is nevertheless connected to his life as a gay man in Los Angeles. Frequently, he focuses on places and stories linked to gay culture, and evokes a fascination with the dark side of Hollywood as found in Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon books.11 In Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds) (1982/84), Johnson superimposes the names of movie stars on cloud images. The letters of the names are set in dark blue italic with a drop shadow, as if they are projected onto the clouds by an out-of-focus projector. What connects this pantheon of movie stars–Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo–is that all of them died early in their careers as a result of a mysterious disease, accident, suicide, or homicide. Johnson’s inclusion of the lesser known Mineo is significant. Mineo co-starred with James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), as well as in Giant (1956), but after 1960, he mainly had supporting roles on TV and on stage. Mineo was an actor who outed himself as gay,12 and was stabbed to death in 1976 in West Hollywood, now known as “Boys’-Town.” In artworks such as Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds), Johnson’s textual aesthetics allow for parallel readings by different constituencies in his audience. “I honestly believe my work is different for gay men of my generation than it is for other people.”13 For Johnson camp is not only a style, it is also linked to language and politics.

Larry Johnson, Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds) (details), 1982/84. Color photographs. Six panels: 20 x 24 in. each. Edition of six. Private Collection. © Larry Johnson.

Larry Johnson, Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds) (details), 1982/84. Color photographs. Six panels: 20 x 24 in. each. Edition of six. Private Collection. © Larry Johnson.

Seen in a larger context, Johnson’s work can also be connected to the so-called Pictures Generation of the late-1970s and 1980s, including artists such as Jack Goldstein, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, Richard Prince, and Cindy Sherman, who appropriated imagery from media culture.14 Referring to magazines, movies, and popular music, their work reflected consumer culture, gender roles and other social issues, post 1968. Some of these artists were part of the influential Picturesshow, curated by Douglas Crimp in 1977, in which they explored “how a picture becomes a signifying structure of its own accord.”15 Crimp’s exhibition raised questions of representation with images that not only depicted, but also influenced, our views of reality. Johnson started his art career shortly after the Pictures Generation became known, and his work can be traced to this discourse. However, rather than appropriating images, he appropriated narratives.

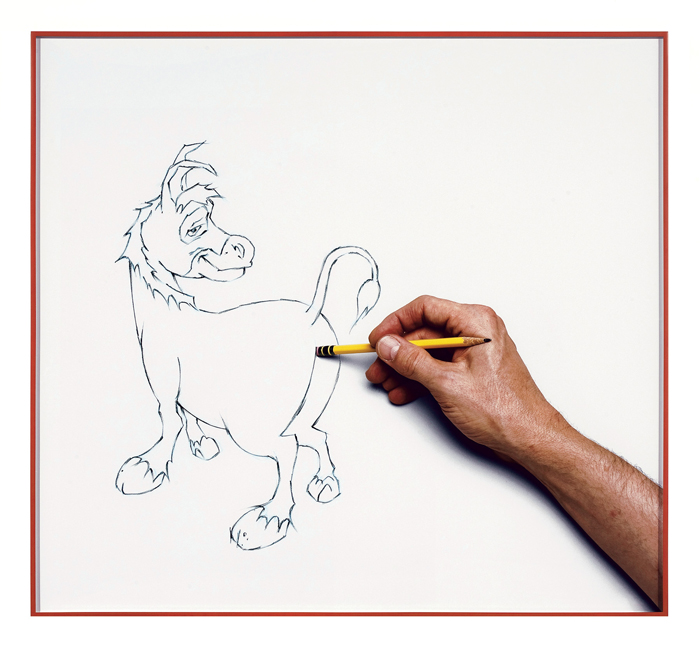

While in the 1980s text dominated the picture plane in his oeuvre, images slowly came to dominate his visual arena in the 1990s. In his most recent works, no text is to be found at all. Johnson also moves away from celebrity references. Instead, he focuses on different modes of representation, exploring pictorial strategies that shift our perception of imagery. In Untitled (Giraffe) and Untitled (Ass), parts of a series from 2007, we see pencil drawings of animals rendered in a cartoon style reminiscent of the 1950s. In each, a photographic image of the artist’s hand holds a pencil that penetrates the drawn animals from various angles. We might wonder about the relation between the “signified” and the “signifier,” when we see suggestive images of a creator having pictorial sex with his creations. These photographs are camp in that Johnson evokes nostalgia for a time when animated figures were drawn by hand, while teaming that with gay desire.

Larry Johnson, Untitled (Ass), 2007. Color photograph, 57 5⁄8 x 62 5⁄8 x 1 1⁄2 in. framed. Edition of 2. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Purchased with funds provided by John Baldessari. © Larry Johnson.

Photography is a constant in Johnson’s work; even if he starts in another medium, the work is ultimately presented as a photograph. The photographic surface gives his oeuvre a slick, cohesive look.16 Walking through the exhibition at the Hammer, I found myself wishing for a more visually haptic experience, in which my eyes were allowed to wander around the physical edges of collages or a drawn line; I wanted to actually see the pencil line on paper rather than the perfectly reproduced drawing on photographic paper. But Johnson denies the viewer the pleasure of looking at other materials. Through his consistent use of photography, Johnson’s mediated surfaces convey a sense of emotional detachment to the highly emotionally charged contents. After all, his works are not private confessions in diary prose and penmanship, but crafted and mediated pieces referencing mass culture combined with confessional tones. In this respect, I see photography and its glossy surface as a unifying format that emphasizes the public over the private, the reproducible over the original. Johnson’s visual language actually engages us to think about mass-produced narratives, gay concerns, and camp practice by highlighting various styles of American postwar culture and revealing polysemic pleasures.

Doris Berger is an independent art historian, writer, and curator relocated from Berlin to Los Angeles. Former director of Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany, she recently published her PhD thesis on the depiction of visual artists in biopics.