Participants: Kim Abeles, Eugenia Butler, Allan Kaprow, and Michael Rotondi

Witnesses: Judith Hoffberg and Cuauhtemoc Medina

Introduction by Leila Hamidi

I met Eugenia Butler in 2000 when I was a student at Otis College of Art and Design. I was looking for an internship and my professor, Dr. M.A. Greenstein, suggested that I work with Eugenia on her thirty-five-year retrospective, Arc of an Idea: Chasing the Invisible, at the Otis Ben Maltz Gallery. On my first visit to Eugenia’s studio, I remember initially being taken aback by her candor when she told me that she cherished her workspace and studio time, and wasn’t thrilled at the prospect of having to share either with a stranger for two days a week. At that time, I could hardly imagine the impact Eugenia would have on my life as a mentor and dear friend. But she has become so thoroughly woven into my life that since her untimely passing in 2008, I regard her daughter Corazon del Sol, whose words and thoughts are incorporated into this introduction, as my sister.

If there were moments where I was daunted by Eugenia’s honesty, there were countless other times during which our conversations soared. She was a voracious reader of all subjects from the intricate social structures of bonobos to psychologists’ theories of anger as a biological contagion. I recall that one of our first conversations was about the smallest particle of matter. The book she was reading at the time was on theories of quantum physics. Through her vivid description, the room transformed, and I saw matter as energy for the first time, moving in cyclical patterns through a doughnut-shaped form. Objects and the spaces around them were no longer divided by a clear boundary as matter spiraled freely from one to the other and then back again. In Eugenia’s hands, even the most rarefied ideas served as metaphors and lenses through which to better understand life.

Eugenia Butler, A Congruent Reality, 2003 reconstruction at Ben Maltz Gallery of 1969 original at San Francisco Art Institute. Time based perceptual/ conceptual event (conscious presence within the continuum of time). Text on aluminum plate. 8 x 64 inches. Photograph by Gene Ogami. Image courtesy of Eugenia P. Butler estate.

These types of conversations would take place during breaks from my “real” work as her intern. My task: to transcribe The Kitchen Table, a project from 1993 in which Eugenia invited twenty-six of her favorite artists from around the world to have conversations with her over meals at Art/LA, an annual art fair held at the Los Angeles Convention Center. The conversations, which had loose frameworks or themes, took place in a secret room with cameras that streamed the talks to television monitors displayed in public spaces. Conceived and organized in under three months, the project was an enormous leap of faith on Eugenia’s part, both conceptually and logistically. It was her belief that the project and the deep exchange of ideas it proposed were a valid form of art. And it was indeed her ability to infuse others with this belief and her enthusiasm that allowed The Kitchen Table to emerge in the highly collaborative form that it did. Pulled together during a time of great financial struggle in her life, Eugenia was able to convince the fair organizers to give her a free booth; she arranged for the catering and wine to be donated, and secured free accommodations and discounted airfare for participants. With this same rigor and determination, she was able to engage artists in the project whose work she loved, some of whom she had never met.

But the story of Eugenia Butler and The Kitchen Table can’t be adequately told without first elucidating her family story and unraveling her somewhat complicated history with her mother, with whom she shared the same name. Eugenia Butler the elder, a gallerist on Los Angeles’ original gallery row on La Cienega Blvd in the 1960s, was a pivotal figure within the arts. She gave Conceptual artists such as John Baldessari, Dieter Roth, Joseph Kosuth, James Lee Byers, Edward Kienholtz, and her daughter Eugenia some of their first exhibits. As a gallerist, Eugenia (the mother) cultivated a salon-type atmosphere at her home with artist and writers–both local and those visiting from abroad– regularly stopping by for meals and great conversation. Eugenia (the daughter) cites these early experiences of participating in a deep exchange of ideas as her inspiration for The Kitchen Table.

However, the flip-side of these intellectually stirring moments was a less-than-ideal family life, to which Eugenia readily alluded in some of the talks. It should be noted that mother and daughter did not always share the same name. The mother, who originally went by the name Jeannie, legally changed her name to Eugenia when her daughter was sixteen years old, which is indicative of the complex, intertwined nature of their relationship. On a later occasion, Eugenia (the mother) was at Prospect 69 in Dusseldorf for the purpose of representing her daughter’s work. During the exhibition, the mother posed as her daughter, without her daughter’s knowledge. Under ordinary circumstances, it would be challenging to give an under-recognized artist like Eugenia her due. The task is doubly difficult when her story is so easily confused or conjoined with that of her mother, who also has a rightful place in contemporary art history.

Although Eugenia spoke openly about her complex relationship with her mother and career setbacks while under her mother’s management, her work remained unabashedly sincere and perennially curious about the people and world around her. She maintained a rigorous and prolific exploration in her studio practice throughout her forty-year career, while continuing to hold public dialogues.

Throughout the years, Eugenia was able to hone in on the elements that contributed to a successful conversation. Perhaps the best way to illustrate Eugenia’s continually refined vision for her public dialogues is in her own words, as excerpted from a letter she sent to participants of an upcoming 2004 talk, Fire in the Library: A Laboratory with Velocity, at the Clark Memorial Library in Los Angeles: …

I am convinced that there is an order of intelligence that we access collectively–one that cannot be reached alone. The paradox is that although I have invited each of you because of your expertise and knowledge, what will make this experience the most fruitful is if we meet in a state as close to “not knowing” as possible. In this way we can access those parts of our individual and collective intellect that reach beyond the everyday analytical mind.

In creating this conversation, it is important to be in our most intelligent, most generous selves, when being heard is less important than creating something together. Equally important is to let the default mechanisms that sometimes emerge when we are in a group of strangers to recede into a larger vision of support and kindness.

One of the things that I have learned in the many conversations that I have done is that even without a formal structure, these conversations tend to take on their own shape of exposition, engagement, transformation and resolution. Most important is for you to relax, be willing to play, and allow things to happen. The more we can get to a primary discourse where language and ideas flow out for the first time–when we are thinking and talking at the same time–the more incendiary and exciting the experience will be for all of us.

I had the great fortune of working for Eugenia on and off for nine years, and I remember refining the above letter with her over the course of an afternoon in her studio. As witnessed in her public dialogues and her studio practice, her work was born of a generous spirit that fostered dialogue, shared space, and community.

Over the course of several issues, X-TRA will print excerpts from the series of eight Kitchen Table talks. The following was selected from Kitchen Table Talk 7: Our Relationship to Our Environment, which took place in Los Angeles on December 5, 1993.

Eugenia Butler: This is Kim Abeles and Kim is going to sit right here. Let’s see, Allan Kaprow, I think I’ll put you right there; Michael Rotondi right here. One of our witnesses is Judith Hoffberg and our other witness is Cuauhtemoc Medina. And let’s sit down, once again.

Allan Kaprow: Where are the Harrisons? [Referring to Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison]

EB: They got the flu. I just talked with Newton last night and he could hardly speak. Actually, somebody was just telling me about the way they do the flu shots. Do you know about this? Evidently the virus makes a yearly pilgrimage. It first surfaces in China, so they go there to get it early in the cycle, and then they bring it over here and do some sort of amalgamation which makes the flu shot. Isn’t that fascinating?

Kim Abeles: Is that why they call it the Beijing Flu?

AK: I didn’t know this. This is very interesting. To think I came all the way to hear this. This is a privilege.

Michael Rotondi: Does the cycle start at the same time every year?

EB: I don’t know that.

MR: Could you find out and get back to us?

EB: Of course, I will.

AK: And don’t forget to call him [referring to Cuauhtemoc Medina] down in Mexico.

EB: Actually, he’s a neighbor. He lives here.

[…]

MR: Well why doesn’t he get to sit down at the table?

EB: Well, actually, we were talking about that this morning. I’m actually a little uncomfortable about them not sitting at the table. Maybe they should sit at the table, I don’t know.

AK: Why not? You’re making me nervous over there. Sit at the table.

MR: Did you swear them in yet? Did you promise to observe the whole truth and nothing but the truth?

Cuauhtemoc Medina: Yes.

EB: Let me tell you a little bit about the notion of the witness. [To Kaprow:] I knew you were going to come in and start fucking things up. Fucking things up is really not the language; fiddling is better. How about that?

AK: Fiddling…right!

EB: It’s not in any way negative.

AK: I didn’t think so, because your eyes lit up.

MR: I think he’s the antidote to you.

EB: Oh, you mean like I don’t fuck things up? Right!

The notion of the witnesses came up three or four weeks ago because I was aware that we had these technological witnesses, which are the cameras, and that feels like a certain kind of a witnessing. Because this piece is very collaborative–it’s like a microscope looking at itself, looking at itself, looking at itself–I thought it would be interesting to have the presence of human beings as witnesses as another layer of observation.

This occurred to me last night, when some of us were talking about the difficulty of not writing about our own work–about having some of the organs of dissemination of information be controlled or be driven by people who don’t necessarily understand their work. This morning I decided that the way I’m going to get the information about this piece out is to have a central core of observation, and then any of the artists who want to talk or write about their vision of this whole entity can do so as a continuation of this layering process. […]

But I want to go back to the witnesses for a minute because I’m still worrying over this in my mind. Do you think it’s more appropriate to have them at the table? What’s the consensus?

CM: I like sitting here.

AK: And Judith?

Judith Hoffberg: Yes, it’s an extraordinary situation–for someone who has to keep quiet for the first time in her life.

EB: Well, we’ve resolved that. Are you hungry…should we start? [Participants serve themselves.]

[…]

MR: As you were talking, I was thinking about this notion that all art has to be written about, and wondering: When are going to move beyond that? What I think started with Allan, and is now becoming very evident in architecture, is the idea of taking in primary information through the body. As opposed to the period that we’ve previously gone through in architecture, and in art, where experience can only be experienced from the eyes to the mind. […] That period was important to go through. But I think right now what we need to be focused on is that art doesn’t necessarily have to be written about in order for it to be understood.

EB: I think that’s true. But, in this particular case, there has been so much conversation during and outside the tables about the way this is affecting people’s lives and the aspects of it that coincide with a real need for community and a real need for dialogue and a sense of artists taking an initiative in making this happen. The sense that I get is that it’s really important to make available not only the art piece itself, but the process of it, the way that it’s happened, and the intensive, collaborative nature of it.

MR: Well, it’s like a building, for instance. You produce a building and you can photograph and document it, which tries to somehow convey the intentions of the people that produced the work. But in fact, it doesn’t convey that at all.

KA: It becomes a graphic. It’s like if you have a beautiful art exhibition. Typically, people don’t get to see the exhibition–they see the reviews or the articles about it. And the image that accompanies [the writing] is not necessarily the best piece of art, but it’s the one that translated best as a graphic element.

[…]

EB: But it’s not documentation and it’s not really autonomous because the writing about it is coming from the experiencing of it. It’s coming from within the piece rather than from without the piece.

MR: Years ago, I was reading a comparison that conveyed the notion of the absurd and it used, as an example, Beckett and Camus. In the case of Beckett, form and content are one and the same. In Camus’s case, he uses the tradition of intellectual thought to construct a logical argument to convince you that the absurd exists. So, form and content aren’t related to each other. I think right now, the possibility is for putting form and content back together.

EB: Yes, that’s what we’re talking about. And it almost has a viral nature. I see the act of writing about it in this way, as a sort of extension into the bloodlines that are moving out. It doesn’t have closure; it doesn’t have a closed identity.

[…]

KA: It is also realizing the power of something being interdisciplinary. In the seventies everybody got so specialized that none of us can speak easily to one another anymore. Because of that kind of isolationism, you have humanists and architects here, and scientists or computer people over there; nobody is interacting. What you’re supposing is that if you merge art forms and scientific forms that you wind up with something that will pull us together. The only problem I have with what you’re suggesting is the conscious effort it takes to do it; it’s a little contrived.

EB: What do you mean? What is the conscious effort about?

KA: Well, if I think back to some critics I’ve known that have tried to do what you’re suggesting, their critique is not just about the work–describing the work, or relating it to other art forms or previous history–but instead it becomes something like a play or a narrative; a short story. There was always something contrived about it that wasn’t really heartfelt or coming from the muse. It was coming instead from a conscious effort to do something different, more coming out of a frustration.

MR: It could be thought of in that way. But I think we’re hopefully at the tail end of a period where the critical writing or theoretical description of the work was seen as the work itself. A majority of people didn’t have an interest in being thoroughly engaged in stuff. They were like tourists going to Stonehenge or to Monument Valley–instead of being part of an enactment of a ritual and feeling what it’s really like. You drive by and never get out of the car. […] It seems to me that now there’s a renewed interest in trying to rediscover what has been missing to spirituality. Not religion, but spirituality.

[…]

KA: I keep thinking that art is the new religion–or spirituality, if you want to say it in a more polite way. And it is steering us in that direction. It’s the very reason you’re having us sitting here. People are watching us on a video monitor out there.

MR: What’s the title of this?

EB: “The Environment.” The environment is really the connection between art and reality. It’s more of an underlying thought form.

KA: Are we turning out to be televangelists?

EB: Are we televangelists now? Send money here!

KA: You’re saved! Don’t you feel better?

[…]

EB: There’s something really interesting and I can hardly wrap my mind around it here, but it’s to do with getting into the minds of those most resistant and subliminal paths of information. But it’s a little bit beyond reach.

MR: I think Allan could probably piece it together. He’s a master of the non sequitur.

AK: I don’t know if I should thank you or beg my pardon.

EB: Did you see that movie Mindwalk [1990]?

AK: I never saw it.

EB: There’s one scene in the movie where a scientist and a writer are standing in a castle and he gives the example of an atom. It’s as if the castle is the nucleus, and way out there is an electron and way out there is another electron. And somehow this movie weaves together a vision that makes you understand in a much more corporeal way how it all connects up.

MR: Like My Dinner with Andre [1981], but a different type of discussion.

AK: That’s a very good comparison. My Dinner with Andre, which I did see, approaches the question of experience with a kind of recollective point of view. […] I’m really interested in the point of view of experiencing experience. The main character, Andre, tried to remember certain highlighted experiences. And by implication, of course, there are more subtle versions [of experience] to which we are not attentive. Such as impatience at a red light, or, since I’ve just gone to the dentist recently, wondering if that was that the enamel on my tooth that just broke off, or if it was a pebble in my food.

Eugenia Butler, The Kitchen Table, Talk 7: Our Relationship to Our Environment, ART/LA 93, Los Angeles Convention Center, 1993. Bottom right photograph, from left to right: Kim Abeles, Eugenia Butler, Cuauhtémoc Medina, Michael Rotondi, Allan Kaprow, Monica Castillo. Stills from the kitchen table Hi-8 videos. Images courtesy of Eugenia P. Butler estate.

EB: Oh, really?

MR: [To Butler:] I sure hope you got insurance. I’m about to fall out of my chair. …Oh, my back!

EB: You are mean today. It’s true! I want to amp it up. I want to see you really get mean.

MR: Then I’m going to tell you what experience really is.

EB: Just you wait and see!

MR: I’m afraid I’ll lose.

AK: Now here’s something that you might be able to win.

MR: Talk slowly, Allan. [Rotondi pretends to take notes.]

EB: It’s those fucking architects. They always want to win.

AK: Okay, this is how you’ll win. Now listen. If you look at ninety-nine percent of architecture magazines and nearly all the books, you’ll find that the pictures of interiors, exteriors, sites, and aggregates of buildings have no people in them.

KA: Oh, right. The Ansel Adams photos also.

AK: The reason is that the work of art, in nineteenth century terms, became autonomous and separate. It was equivalent to some spiritual entity above and beyond the contamination of life. And so the critiques within architecture recognized that this people-less artwork that was being conceived–sometimes brilliantly–needed some people. You know, there’s always that backlash period where there’s a kind of reassessment. Now, at last, again we can really look at artworks where it was verboten for a while because it was considered elitist. Now that’s where experience, it seems to me, comes in. You cannot experience big waves of social forces in your head.

EB: No, you cannot.

MR: One point that I would be interested in making is having us eliminate judgment, not saying, “That is bad and this is good.” When you look at these movements in art and architecture as a continuum, you realize what we’re doing right now wouldn’t be possible unless what came before us was done.

Abstraction in architecture and art was essential in order to move it from where it was to where people wanted it to go. I think that what we’re constantly doing is disintegrating in order to try to develop the integrity of each of the movements, and then we go back through another phase where we’re trying to reintegrate.

I think that [we are presently in] the period of reintegration. But we wouldn’t be talking about a lot of the things that we’re talking about right now at the sophisticated level that’s occurring right now in art and architecture if these ideas had not been proposed in the sixties. A lot of the things that are being discussed right now are part of the thirty-year cycle.

[…]

EB: Absolutely. You know, I was just struck by something that I wanted to acknowledge to you, Allan. I doubt very much that I would be doing what I’m doing today if it wasn’t for what you did as an artist, and what you continue to do. Here is this incredible connection right at this table.

AK: One other thing I just want to add in parentheses is that I made sure that it got out in writing. Nobody else was going to do it and I happened to be an academic on top of things. So I said: “Listen, I’m not going to let those journalists alter it.” I took care to actually write about it, but it turned out nobody read any of it; I was a fool in that respect.

KA: But it’s still in the libraries, Allan. […] All of what you’re saying brings up in my mind that right now the goal is to get art out to people. It’s always so funny to me with public projects that are socio-political, of which I have been part, that you’re always trying to force the problems that are theirs every day down people’s throats. When there are public art projects, like with the metro stations where it’s going to be so extensive, it’s an opportunity to bring all kinds of art to the people–not a list of their problems.

MR: See, I would argue with that. […] You can produce a mediocre metro station, which doesn’t engage the body at all, and provide surfaces for art, but there’s no relationship between the art and the architecture as making a total experience.

KA: But don’t you think there has been a change toward that with public art, where the artist and the architect are brought in at the same moment?

MR: Usually someone comes and says, “This is your lobby. Do whatever you want with the lobby. These are your options.” I’ll take this place and that place and I’ll slap them together.

KA: No, that’s the more typical way.

EB: Michael, let’s do a metro station together.

MR: It’s not that easy. There’s a…

EB: I know; there’s a process. Well, anyway, I just put it on the table.

MR: There’s a sequence. […] As you move up in size and scale in architecture, you’re dealing with ideas that are pretty old because they’ve had to have been around long enough in order for hundreds of people to accept them and allow you to do your work. Part of your job as an architect is to explain your ideas in terms that other people can understand and advocate as their own.

EB: So there is a process of conceptual interweaving. How can an architect and an artist have a successful collaboration if an architect is dealing with very old ideas? Actually, an artist is also dealing with ideas that have been generated and regenerated.

MR: […] It took seventy-five years for artists and architects to start dealing with relativity; whereas right now, it takes ten for us to start dealing with chaos theory.

EB: I’m not sure I agree. There is a very interesting book called Art & Physics [1991], written by a professor in San Francisco [Leonard Shlain], in which he goes back four or five hundred years and investigates the simultaneous emergence of new understandings of the world that actually happen parallel in art and science–that the artists were finding these things out intuitively and scientists were finding them out intuitively, but with a different set of tools.

SUMMARY OF BREAK IN DIALOGUE:

Kaprow mentions the trend of artists nowadays being highly educated with interests in other fields. He also talks about his experience picking the brain of a cognitive scientist who is a fellow professor at the University of California, San Diego, and whose studies try to pinpoint and understand intuition.

KA: Intuition to me is something that is there but is stifled throughout your life by outside forces. To me, the last half of a life is about trying to regain it.

AK: Wait, let me finish. I’m sure you’re recognizing something there, buy it’s not what I wanted to say. I began to read this sociologist’s work, which was subject to real scientific testing to try and get at why intuition strikes us as being elusive and not subject to science at all. So, the point is: Is any human being equipped with sensors with the capacity to understand or intuit that a post-rationalist society, such as ours is, chooses not to recognize?

MR: Most often when we talk about memory, we talk about the memory that begins at birth and ends at death. And currently in the sciences, they talk about a memory that’s a deeper cellular memory. What Jung used to call “the collective unconscious” and Rupert Sheldrake calls “morphogenetic fields.”

AK: That’s interesting.

MR: And there’s others in esoteric philosophies that have stated for a very long time that all structures that exist outside the body already exist inside the body. And that everything that’s happened since the beginning is stored in each and every cell and is accessible through certain disciplined acts, meditation being the most obvious one. But then a meditative act can also be art making. That information is released and sometimes it’s released in such quantities that the person it’s being released within also has the skill to do something with it. We call it genius. But for me, I think I call it intuition, instinct. Maybe it’s possible for us to learn how to tap into that. On the one hand we’re satisfied that it isn’t hocus-pocus, because there is somebody with an advanced degree saying that it does exist. And then, on the other hand, it satisfies our spiritual need to say that there are things that are un-knowable out there.

EB: But I want to go back to what you were saying. I’m going to get a little out there here. There is this interesting thing happening here at the table for me between the two of you [laughing and speaking to Rotondi and Kaprow].

AK: You mean the two of us?

EB: The two of you.

MR: And the two of you [referring to Abeles and Butler].

KA: I’m curious if we’re thinking the same thing.

EB: I’ve noticed that you both have a very developed skill to take the podium and hold it. And although there is a lot of value in what you are saying, I’m experiencing a lack of conversation. I feel outside of a lot of what you’re saying. I’m feeling as though there’s a territory here and a territory there and to a certain extent there’s a joined territory, and it’s interesting.

[…]

KA: There’s also a different dynamic. There’s a certain reliance on external information. I enjoy listening to you talk about experience, but I’m also sitting here doing it and I was kind of aware of that. Because of your history as an artist [to Kaprow], it’s hard for me not to sit on the edge of my seat with what you’re saying, which I think lends itself to a difficulty making a dialogue instead of being just really curious about your take. You talk about that experience of talking to people outside of your field, whereas my response with art is more emotional. Maybe I look at art in a romantic way–that it’s the only discipline that allows the possibility of an extended dialogue because it incorporates the other disciplines. And so, a lot of what you’re saying are things that I tend to look at more as an experience. […] And if I interrupt you [to Kaprow] too much, I keep getting concerned you’re going to yell at me and tell me, “Let me speak.” [Laughing.] I’m serious, I’m sorry.

MR: Yeah, but that’s your problem, not his.

KA: I didn’t say whose problem it was.

AK: But that might have been the case if I was a woman. Suppose Gertrude Stein was sitting here.

KA: I would be sitting here with my tongue hanging out. That’s my heroine.

AK: Well, she’s one of mine as well, so I picked someone that we could relate to. It’s interesting because what you’re saying is that the mode of discourse is not so comfortable, or that you’d like to feel that you have the same freedom of discourse as you do in your art.

EB: What do you mean by that?

AK: That they could be of the same substance, and I’m skeptical about that.

EB: Why?

AK: Simply because our modes of communication, especially verbal, have become so adept at separating something from its mode of expression. […] Kim wants to join them. I mean, that’s fantastic. I can’t.

EB: But you were the person who said to me, “Why don’t we avoid having a high-falutin conversation?”

AK: You guys started it. I stood silent for a bit.

EB: I guess what’s interesting to me is: How do we conjoin low-falutin conversation and discourse?

AK: Why low and high?

EB: Let’s just put it out on the table without saying: why low and high? There is something both fascinating and disturbing to me about the way you are defining discourse. It feels high-falutin and it feels very distanced.

AK: That was the point that we were making. […] When you decide to have a group of conversations about big, high-falutin topics such as “the environment” or “power,” you’re not talking about: “Well, now what did you do today?” […] We’re addressing immediately that kind of claim of seriousness.

EB: I don’t agree. I really don’t agree because think that it depends on your definition of terms. To me, environment goes from right here, to right here, to all the way out. And power to me is who I am as a human being and how I use my life and my talent and skills.

[…]

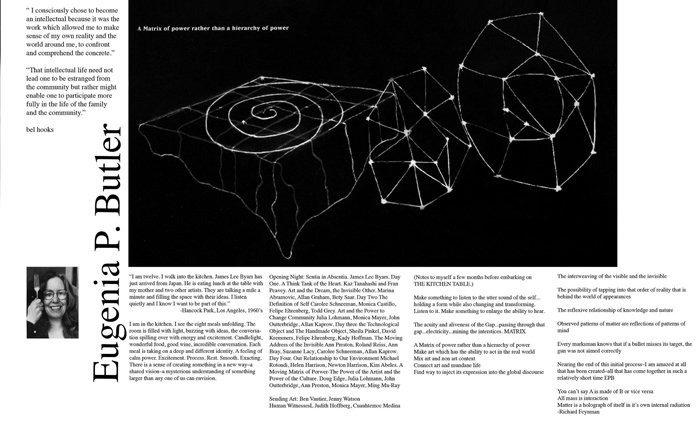

Eugenia Butler, The Kitchen Table (poster), 1993. Text and drawing by Eugenia Butler. Screenprint. 24 x 36 in. Photograph by Christian Krieger. Image courtesy of Eugenia P. Butler estate.

AK: We can talk about empowerment or the corruption of power. It’s not idle conversation. And I assure you, any of the most beautiful evenings that I can remember have occurred around food. I think this is a lovely meal, but this is the first chance I’ve had to say I really loved it.

EB: I’m glad.

AK: I generally don’t talk about high-falutin things. So there was a kind of schizoid quality for me here. I’ll speak only for myself.

SUMMARY OF BREAK IN DIALOGUE:

Rotondi talks about the unfinished design of the space where they are eating in the art fair as a factor that led to disjointed conversation. He suggests that there is always a connection between what we feel physically via our surroundings and what we feel emotionally, and that design can’t happen at the expense of product.

EB: I want to go back again to something else–you [to Rotondi] said something very true about this space, which is that it’s an artificial space. This is interesting to me because the connection between art and artificiality is one that fascinates me. […] I was hearing you say you felt as though you couldn’t do what the course of action was laid out to do because you were constricted by the notion of the space. Given who we are, the fact that we’re right here right now and we’re within this space, what does it lead to? What is the natural territory, the point of beauty that this takes us to?

MR: What we’re doing and what this space is are connected. It may not meet the expectations or the intention you set out from the very beginning. But whatever happens is what happens. I mean, the conversation we’re having is the kind of conversation that we would naturally have in a space that’s unfinished. It might have been different two days ago when I came in here and the smell of rosemary on the walls was fresh. All of a sudden I was thinking of when I was a kid and my mother would always cook with rosemary. […] We always ate out of one big bowl, so you learned how to share. It wasn’t the conceptual notion of “share.” You got your hand hit with a spoon if you took too much. If you’re going first, you have to see how many other people are at the table so you know how much to take out. If you took too much in the beginning and the last person ended up with nothing, you got busted by my mother. Which is probably why I became an architect. It’s special; taking pasta out of a big bowl, you know? I mean, it was sort of a subtractive process, which is conceptual.

EB: But conceptual is also additive.

MR: I was just thinking that an ideal collaboration would be for me to be commissioned to design an elementary school or a high school. I call up Allan and say let’s collaborate on this, and we start with the programming and I become the person that’s responsible for dealing with gravity. Not to say that we don’t cross over, but we begin talking about the project from the very beginning.

KA: You’re pretty unusual, though, because my experience has typically been that architects always want to drown the artists like little cats.

MR: I’d say architects my age and younger are interested in collaborating.

EB: I think the mechanism for collaboration is not yet understood. I think it still has to be invented.

AK: That’s another whole bag of worms. Because very often what happens with group collaborations is somebody assumes or is assigned leadership and then there is a hierarchy, which is a team, not collaboration. […] I wish the Harrisons were here because they went through some very fascinating years of great difficulty learning how to truly collaborate so that the contributions of each person could be fructifying and one is not more important than the other. Or, at certain times one can be more important than the other. But it was a very painful process of learning that had to develop over a period of years.

[…]

KA: Additionally, with the Harrisons, their work became more public in a sense of working with outside groups. […] Their dynamic probably becomes more sensitized because there are onlookers to give that balance. Well, like the witness–that’s the balance point of being the onlookers.

MR: One thing that runs through most of the creative people I know is that they are empathic. If you take that further out, you reach reciprocity, where there is equality between the two, but the hierarchy can change with each person taking their turn.

EB: That’s very beautiful.

MR: For me it always goes back to how safe I felt emotionally growing up in a family. Whether I broke my arm, cracked my head, or got lost, somebody was going to come looking for me.

EB: You’re really lucky. In my family it was the opposite experience. If someone was going to come looking for me, it was either to crack my head or break my arm.

MR: I should also add that in a large family kissing and biting were both a sign of love simultaneously. It seems to me that your work [to Kaprow] pioneered interactivity in art making through reciprocity and interactivity. Because you were responding from moment to moment, it seemed to me that there was reciprocity between one thing and every thing else.

AK: That was the general sense, to the extent that a system for having that happen was developed. It was essentially providing a very rudimentary game to a group of people who agreed to play it as well as they could. Which meant, because it was so simple, that they had to provide all the details. And I was one of the players, which meant I couldn’t be the director. There was a lot of implicit responsibility given to the participants and you can imagine how much confusion there was. It was giving a lot of responsibility, which at the time was probably a little silly…I was not thinking about the consequences.

EB: There has been a lot of that in last four days. This whole undertaking has been highly collaborative.

[…]

Kim Abeles is an artist who crosses disciplines and media to explore and map the urban environment and chronicle broad social issues. Her work has been exhibited internationally and can be found in numerous private and public collections including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Yucun Art Museum, Suzhou, China; Sandwell Community History and Archives, U.K.; and is archived in the library collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Cooper-Hewitt Publication Design Collection of the Smithsonian. A mid-career survey in 1993 was sponsored by the Fellows of Contemporary Art for the Santa Monica Museum and toured the United States and South America. Edited excerpt from: http://kimabeles.com/

Eugenia P. Butler was a Los Angeles-based artist who played a formative but often overlooked role in the Conceptual art movement. Her early text-based works, with titles like Negative Space Hole and A Congruent Reality, were conceived of as invisible sculptures that prompted the activation of the viewer’s imagination to complete the piece. Aside from an eight-year pause in art making, when she moved to South America to raise her daughter and study shamanism, Butler had a prolific career that spanned over forty years. After returning to the States in the early 1980s, Butler resumed studio practice with a focus on physical objects, including drawings, paintings, sculpture, and furniture. Beginning in 1993 with the Kitchen Table talks, Eugenia also developed public dialogues as part of her practice. She was an integral member of the Los Angeles art community and mentored many young artists.

Leila Hamidi is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles. She was profoundly influenced by her mentor, Eugenia Butler, who impressed upon her the value of collaboration and a deep curiosity for all disciplines. Her interests outside of fine arts have lead to positions with Taschen Books and the Los Angeles-based architecture firm Johnston Marklee. She is currently working as a project assistant for Pacific Standard Time, a Getty initiative to explore the post-war art history of Los Angeles through a network of over sixty partner museums and institutions that will culminate in a series of citywide exhibits starting October 2011.

Judith Hoffberg was an art librarian and curator who was a major influence in the emergence of books as an artist’s medium. Since 1978, Hoffberg had edited and published Umbrella, a journal increasingly dedicated to artists’ books…printed through 2005 and then published online through 2009. [The archive is available at http://www.umbrellaeditions.com./] Over about twenty years, Hoffberg curated more than twenty exhibitions, including Women of the Book, which opened in 1997 and toured the country for years. She also was an authority on mail art and Fluxus. Edited excerpt from: http://articles.latimes.com/2009/jan/28/ local/me-judithhoffberg28

Allan Kaprow is widely considered the father of Happenings. He performed/exhibited in galleries and museums in the United States and Europe. His most publicized events included 18 Happenings in Six Parts, Calling, Gas, Fluids, and BTU. He studied at New York University (art at the undergraduate level, philosophy at the graduate) and received his MA from Columbia University in art history. He also studied at the Hans Hoffman School of Fine Arts in New York City and later with John Cage. His teaching career included faculty positions at Rutgers, Pratt Institute, the State University of New York at Stony Brook, California Institute of the Arts, and University of California, San Diego. Kaprow began his studio career as a painter. During the 1950s, he co-founded the Hansa and Reuben Galleries in New York; later he was the director of the Judson Gallery. Edited excerpt from: http://visarts.ucsd.edu/node/view/491/55

Cuauhtemoc Medina is an art critic, curator and historian. He holds a Ph.D. in history and theory of art from the University of Essex in Britain and a bachelor’s degree in history from the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Since 1992, he has been a full time researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Esteticas at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico; he has also taught at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. From 2002 to 2008, he was the first associate curator of Latin American art collections at the Tate Modern in London. His recent publications include “Hacia una nueva anarquitectura” in Tercerunquinto: Investiduras institucionales; “La oscilacion entre el mito y la critica: Octavio Paz entre Duchamp y Tamayo” in Materia y sentido: El arte Mexicano en la Mirada de Octavio Paz; and “Entries” (with Francis Alyes) in Francis Alyes: A Story of Deception. He also directed the Seventh International Symposium on Contemporary Art Theory and writes the fortnightly art criticism column “Ojo Breve” for Reforma newspaper in Mexico City. Edited excerpt from: http://www.pbs.org/pov/elgeneral/bios.php

Michael Rotondi, FAIA, has practiced and taught architecture for thirty years; he has always been based in Los Angeles, where he was born. He was a founding partner, along with Thom Mayne, of Morphosis (1975-1991); together with Clark Stevens he founded RoTo in 1991, where he is currently the sole principal. Rotondi teaches at SCI-Arc, where he was the director of graduate studies between 1980 and 1987, and was the school’s director from 1987 to 1997. He has also taught at numerous other universities. Some recent and current projects include: Pacoima City Hall and Public Plaza; Boys and Girls Club of Hollywood teen center; The Silver Lake Conservatory of Music; Liberty Wildlife Center in Phoenix, AZ; Hansen Dam Skate Park; Madame Tussauds, Hollywood; Prairie View A&M University School of Architecture; La Jolla Playhouse at UCSD; University Research Institute, Louisville, Kentucky; reconceptualizing the re-use of malls in Los Angeles, New Mexico, Palo Alto, and Dubai; two Buddhist education campuses in Tehachapi and Santa Cruz, California; and the Thomas Merton Contemplative Retreat in Kentucky. Edited excerpt from: http://www.sciarc.edu/portal/people/ faculty/portal.php?people/faculty/all_faculty.hml#section18