Kim Light Gallery—Early 90s, Installation view, Kim Light/ LightBox, 2007. Photo: Joshua White.

Curator Carole Ann Klonarides’ version of 1990s Los Angeles art history doesn’t easily fit the bad-boy, “Helter Skelter” model that has been widely established over the past fifteen years. While the popular appeal of a fin de siècle, west coast aesthetic marked by tawdry referentiality and its ironies has barely had the chance to wear thin, Klonarides is already offering an alternate account of the artists and ideas that emerged from pre-Y2K Los Angeles. In her recent exhibition, Kim Light Gallery—Early 90s, Klonarides identifies a group of artists that embraced the dominant critical discourses of that time—namely identity politics and post-modern theory—while formally challenging the didacticism and self-reflexivity of earlier generations. Further connected by their shared association with long time L.A. dealer Kim Light, the thirteen artists featured in Early 90s evince that there is still much to ascertain about art in the last decade.

At the start of 1992 (a year regarded as the collapse of 1980s contemporary art market glory), MOCA curator Paul Schimmel presented what he identified as a new, angst-ridden Southern California art scene in his exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s. Designed to “demand a visceral rather than a purely intellectual response from the viewer,” the show reflected a collective impulse towards art that was “in your face…raucous, loud and aggressive…and unrelenting in its disposition.”1 As demonstrated by Chris Burden, Mike Kelley, Liz Larner, Paul McCarthy, Manuel Ocampo, Raymond Pettibon, Nancy Rubins and Robert Williams, to name a few, Helter Skelter’s objects and images were likewise characterized by dark humor, representations of violence and sexuality, callous masculinity, and symbols lifted from low-brow cartoons, pulp literature, rock posters, cults and extremist groups. As Schimmel argued, the artists included in Helter Skelter would come to represent a Los Angeles defined not by light and space, but by the heaviness and anxiety that pervaded the close of the millennium.2 Schimmel’s insight (or perhaps self-fulfilling prophecy) has seemingly won out today as most, if not all, of Helter Skelter’s sixteen artists have sustained successful careers while epitomizing L.A.’s renaissance of contemporary art in the 1990s.

Helter Skelter was an undeniably important exhibition, particularly for the perception of L.A. within the gradually globalizing art world, yet it was by no means the sole interpretation of Southern California’s contemporary art at the time, nor should it continue to be today. Even in 1992, Klonarides was beginning to question Schimmel’s easy showcase of L.A’s brooding, alienated, and dispossessed artists; in the winter following Helter Skelter, Klonarides and fellow Long Beach Museum of Art curator Noriko Gamblin presented Sugar ‘n’ Spice, an exhibition conceptualized in response to the MOCA blockbuster.3 Comprised of thirteen Southern Californian women artists, Sugar ‘n’ Spice disallowed “the existence of characteristic perspectives, trends or styles determined by region” in favor of “unique artistic visions, in works of all media, which address issues of identity, often related to gender, and their expression in terms of art.”4 In short, the exhibition—which included work by Hilja Keading, Jennifer Steinkamp, Diana Thater and Pae White—prescribed a detox from Helter Skelter’s bloodlust and adolescent fantasy through a cultivated emphasis on conceptual, theoretical and structural art practices.5

Kim Light Gallery—Early 90s, installation view, Kim Light/ lightbox, 2007. Photo: Joshua White.

Kim Light Gallery—Early 90s seems to pick up where Sugar ‘n’ Spice left off, that is, laying to rest more of the regional myths spun by Helter Skelter while building upon another episode in Los Angeles’ often overlooked (or not-yet-scrutinized) past. As the fall exhibition at the Culver City gallery, LIGHTBOX, Early 90s gathered works from thirteen artists featured in solo shows at Kim Light’s Hollywood space between 1992 and 1994. In just two years, Light, with the help of Jeff Poe (now one-half of Culver City pioneers, Blum & Poe), supported the experimental practices of young artists like Skip Arnold, Karin Davie, Kim Dingle, Karen Finley, Gregory Green, Monica Majoli, and Dani Tull, artists whose work was perhaps too green, too heady or too meticulous to be grouped into the sexy, anti-establishment subculture revealed in Helter Skelter. Light’s was a program of primarily west-coast artists who were exploring (in addition to painting and sculpture) conceptually-based photography, performance, video and installation, the kinds of media reinvigorated by the collapse of an object-based art market.6 And while her artists were working alongside, and often in collaboration with those touted by Schimmel and other taste-makers of the 1990s, some are slowly being separated into reductive categories by a history that is still in the making.

Perhaps because of this nascent, in-progress hitoricization, the complete installation of Early 90s risked coming across as a miscellany of unlike things. As viewers entered the space, they first encountered a small monitor displaying Skip Arnold’s 1992 performative video, Hood Ornament as well as documentation of his 1993 performance The Axis Powers Tour, in which the artist crated and shipped himself throughout Europe. While the latter demanded a context that could be pieced together after careful study of Arnold’s delightful “tour” correspondence on-view, an adjacent gallery presented work that was more immediate in its legibility. This space was defined by a collection of strong, abstract works, which seem to have retained the innovation and elegance of their creation fifteen years ago.

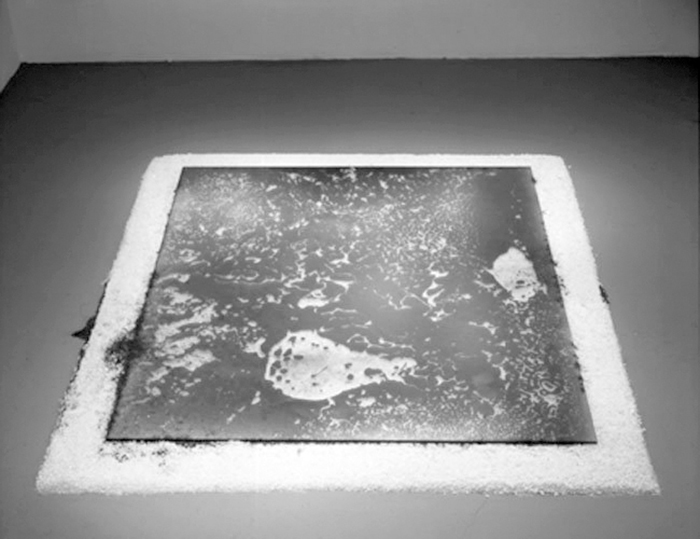

Anya Gallaccio, Red on White, 1993. Blood, glass, rock salt; 74 x 64 x 1 inches. Courtesy of Blum and Poe.

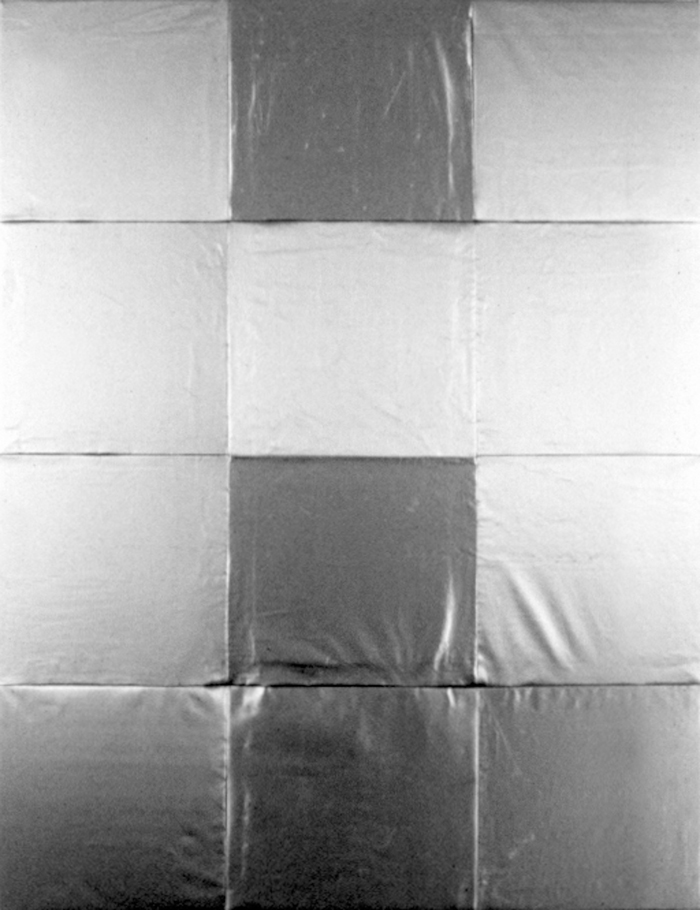

Existing as a set of instructions and recreated by Klonarides, Anya Gallaccio’s gorgeous sculpture Red on White (1993) is a simple sculpture that immediately evokes the feminine body or menstrual blood. Installed on the gallery floor, the piece is formed by kosher cow blood poured over a square area of rock salt and covered by a plate of glass. This work—much like Jason Fox’s nearby fleshy, abstract painting on sleeping bags, Drosion (1993), and Karen Finley’s large memorial installation, Written in Sand (1992-2007), which filled a side corridor of the gallery—subtly comments on the AIDS epidemic, echoing a culturally ingrained fear of bodily fluids while placing the viewer in direct contact with such. Another simple abstraction, Bruce and Norman Yonemoto’s Achrome III (1993), constructed from the minimal, silver surfaces of stitched-together film screens, is as evocative of the materiality of light as it is of the evolution and eventual obsolescence of technology.

Bruce and Norman Yonemoto, Achrome III, 1993. Silver projection screen, 35 x 20 x 16 inches. Photo: Josh White.

These clean, refined artworks were somewhat compromised by a few seemingly out-of-place works that crowded the gallery and its much needed breathing room. Gregory Green’s Fido (1997), for example—a disarmed missile mounted on the gallery wall—may have once translated as dangerous, analytical, even edgy, but this threat now seems lost on a post 9/11 audience whose understanding of cause and effect (as it pertains to WMDs) is infinitely more complex. Although a more playful piece, Keith Boadwee’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Blue, Yellow, Green & Orange (William, William, William, William, William) (1993) also competed for attention; the series of five color photos, each depicting a pair of male lips surrounded by a face-painted color field, hung vertically to create a fourteen foot-tall zip. These orifices (which Boadwee calls “butt-hole targets”) are at once homoerotic and absurd, reducing the modernist pretensions of Barnett Newman, Robert Irwin or Jasper Johns to fun, uncomplicated fetishes.

This unspecified tension between artworks continued into LIGHTBOX’s second gallery space, which featured another piece by Gregory Green alongside painting and sculpture by Dani Tull, Monica Majoli and Kim Dingle. While these works more closely approximated a Helter Skelter aesthetic, they not-so-subtly espoused their conviction for straightforward gender and sexuality politics. Take, for example, Dingle’s Priss Room Installation (1995); in a wallpapered and linoleum-tiled corner of the gallery, a crib, strewn with trash and ripped stuffed animals, holds two “Priss” dolls (the artist’s alter-ego) in pristine lace dresses and polished Mary Janes. Their menacing grimaces and the messy crayon scrawled across the walls seem evidence of some violent, third-wave feminist temper tantrum. Dingle’s volatile dolls are situated in proximity to Dani Tull’s saccharine watercolors of Dick and Jane-like children caught in psychosexual “oopsies;” in Sniff (Dingle) (1993), a little girl is caught off guard by a daschund curiously smelling her bare bottom. Klonarides’ juxtaposition of these two artists may be a bit heavy handed, but it reveals a continuing occurrence throughout her show, which is that many of these works can still hold up in 2007 and others simply cannot. While Tull’s anecdotal scenes retain a novelty that is still palatable today, Dingle’s installation just seems dated.7

Dani Tull, Sniff (Dingle), 1993. Watercolor on duralene, 42 x 30 inches, framed. Private Collection. Photo: Hank Chinaski.

This mix of fresh and tired artworks (as determined by my own love/hate impression of the show) makes me wonder if it’s all too soon to digest the 1990s into history’s tidy narrative, especially when post-war art historians continue to wrap their heads around the 1960s and are only beginning to articulate the aesthetics of the 1970s. This reluctance towards the nineties is undeniably related to changing tastes in art (my own included) and the perpetual cycles of fashion that have driven its market to the heights we experience today. Los Angles’ art scene of the early 1990s was one that I, unfortunately, did not witness in time. Yet, I can’t help but feel nostalgic for that vibrant moment as it is recounted by Klonarides, a time when committed dealers would take risks on new ideas (despite the weak economy) and if not, then artists would do it themselves, fabricating D.I.Y galleries in their living rooms or garages.8 In this respect, today’s L.A.-based artists are not that far removed from this improvised art scene of the 1990s. As they did more than fifteen years ago, artists are still creating their own, informal exhibition spaces in the face of an often elitist and arguably oversaturated gallery system.9 They continue to find new forms of criticality and political satire and their work continues, naturally, to be hit and miss. Perhaps this can serve as a reminder that any imminent present can be seized by history, even when it feels premature. And as the recent histories of Los Angeles art are slowly institutionalized (in galleries, auctions, universities, museums and archives), more rich and significant histories continue to write themselves, often underneath the radar, to be discovered later.

Catherine Taft is a Los Angeles-based writer and independent curator. Her writing on contemporary art has appeared in magazines including Modern Painters, Art Review, Artforum.com and Metropolis M and in various museum catalogs. She currently curates an ongoing series of video screenings at venues throughout LA and is research and curatorial assistant on the Getty Museum’s forthcoming exhibition, California Video