Diego Velázquez, Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt van Rijn, Vincent van Gogh… Kerry James Marshall added his name to this list of masters in 1980 with A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, a black-black egg tempera portrait of a grinning man in a black hat against a black background. Mastry, the first career retrospective of this painters’ painter, includes many self portraits and portraits of black artists and models in artists’ studios. Yet the only image that depicts Marshall in his own studio is a photograph: Black Artist (Studio View) (2002). At least it seems to be Marshall; that’s his painting on the wall. But the only figure is seated with his back to the camera. The studio is cast in dark blue, as if underexposed. And it is—but only in terms of the so-called visible spectrum. The scene is lit with ultraviolet or black light. The shoulders of the black figure’s white short-sleeved shirt glow. To the right of the frame is a studio table cluttered with tools and brushes, but all that pops in the black light are the neon orange handle of a screwdriver and a neon yellow jar of acrylic paint. Black light, by which to see the black artist; black light that’s really right of blue. Since his 1980 portrait of the artist, Marshall has painted black figures almost exclusively, meaning black-black, lamp black, mars black, and bone black. Such is the inadequacy or withheld precision of the English language, within which, in most of Western art history, the walls are the same white as the people. The minstrel-show bluntness of Marshall’s early paintings of black-black skin and shock-white teeth and eyes is punny but pugnacious. A later work, the totalizing Black Painting (2003–6), almost dares you to mistake it for a monochrome. It takes a close look to make out a detailed interior scene coaxed skillfully from a tight range of blacks: a bedroom, a couple in bed, an Angela Davis book on the nightstand, and a Black Panther flag draped beside the lamp. The carpet that takes up a canted fifth of the picture is the abstraction you thought you were getting, and it serves as the foor for Marshall’s greater figurative project.

The photo Black Artist (Studio View), as reproduced in the exhibition catalog for Marshall’s Mastry, is more or less legible, but as displayed in the museum, its dark hues and protective plexiglass make it not only underexposed, but positively reflective. The artist is in his studio; the table is strewn with paints and tools; the wall above is collaged with reference images; and in the center breadth of the photograph is a work in progress, on unstretched canvas tacked to the wall. The seated figure, his hands behind his head, seems to contemplate the picture in the picture like a view through a window. The painting on the wall in Black Artist is 7 am Sunday Morning (2003). 7 am Sunday Morning is an unusually crisp picture for Marshall, rendered with chilly clarity down to the brickwork of the Rothschild Liquors store and the beauty school next door.

Kerry James Marshall, Black Artist (Studio View), 2002. Ink-jet print on paper; framed dimensions: 50 1⁄8 ×61 7⁄8 x 2 1⁄2 in. ©Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

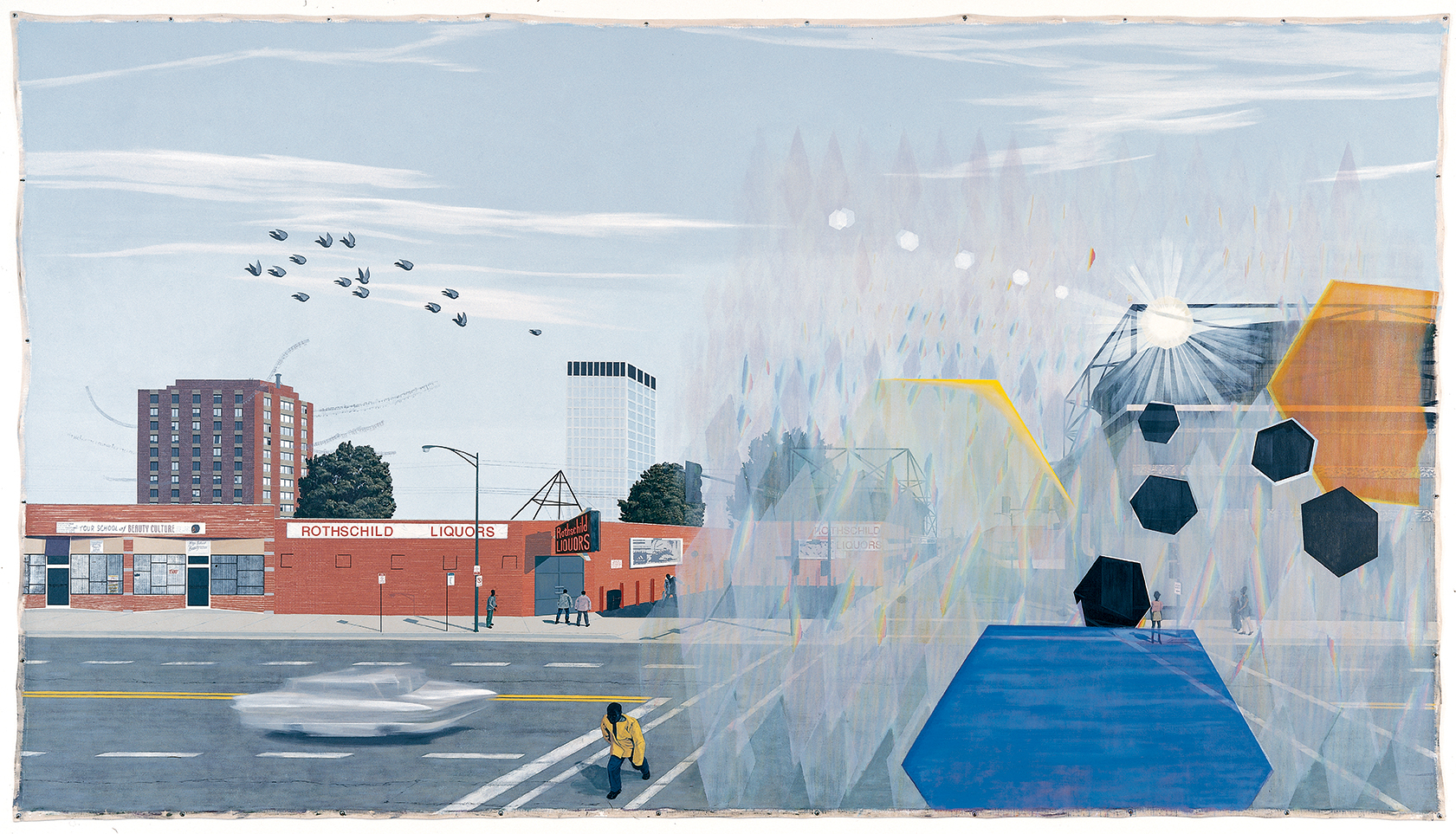

It is a billboard-scale canvas with such a wide sweep that the few finely painted buildings at the intersection have a model aspect, and the figures standing outside the closed liquor store feel like figurines. A cloud-marbled sky takes up most of the image, and the mirage of a giant lens flare buries the rightmost third. 7 am Sunday Morning also differs from Marshall’s oozier, gestural, collage-style paintings of the 1990s in that it is, for the most part, a believable and simultaneous scene. The work crystalizes the painter’s wry relationship to photorealism, a style that he undertakes, as he does all the others, to détourne by mastery. It’s Chicago and it’s early. Notes on a musical staff rhyme with the powerlines; they curl out of an apartment window in the background, and a flock of birds looks stamped on the sky. One man is paused in a crosswalk; to his left is a motion-smeared gray car—a mini Gerhardt Richter, which is to say a nod to another painter’s version of photographic effects. The picture is smooth and at with all the different speeds of its same frozen time. These pictorial tricks, registers of cartoon and photograph, bring to the painting the nested concurrence that is Marshall’s particular revisionism. In other words, it is as accurate a picture as one can paint of how one history persists as a fragment within some other version—a temporal pastiche, accomplished not by collage but by composing a decisive moment.

Marshall’s revision of art and art history remains a painterly one, steeped in Northern Renaissance and Abstract Expressionism. To get into history, he needs to get into the museum, and the best way into the museum is to put on its prevailing conservative mode. But this doesn’t stop him from adding a photographic dimension to his paintings’ reflection. In Small Pin-Up (Finger Wag) (2013), the model’s finger gives off motion trails; in Untitled (Club Couple) (2014), the pair smiles as if for a camera. The lens are blasting across 7 am Sunday Morning resembles or imitates a photographic artifact, but it isn’t one; the paint is paint, and the virtuosity here is on painting’s terms—transparency, layering, and the uncanny potential for a compositional element to be both pictorially resolved and conceptually dazzling—to push out of the frame while flattening the painted object to the wall. The lens flare, or Marshall’s imagination of one, refracts like a sunbeam through a garden hose into a pattern of diamonds edged in rainbows, layered like filmy scales or a ghosted harlequin. Three big hexagons separate into red, yellow, and blue—the foundational elements of painting’s color theory but nothing to do with the elements of a camera lens that actually shape the effect. Between them is a scattering of five smaller, dense black hexagons: improbably black light in broad daylight.

Kerry James Marshall, 7 am Sunday Morning, 2003. Acrylic on canvas banner, 120 × 216 in. © MCA Chicago. Photo: Michal Raz-Russo.

The Art of Hanging Pictures (2003), stands out in Mastry because it is, in fact, an installation of some two dozen photographic prints. Two frames contain grids of photos of churches, many in storefronts or garages—congregations making do. The same photo of a tchotchke swan (a photograph of a TV screen, maybe) is reproduced with two different croppings. On a pair of blocky ledges are vintage-looking double portraits of black couples resting on a couch or posing. In another frame, high and center in the arrangement, is a false-color printout of a famous newspaper photo of four grinning Chicago police officers leading Fred Hampton’s corpse on a stretcher. The emphasis is on pictures, as in, there are so many ways to mount them and then to arrange them in the home: on plexi, behind a matte, or with linen borders; on ledges; on the wall; from a picture rail (the way a “fine art” picture might be hung). Then there are the lay ways: on a low-hanging ledge is a black and-white photo of a woman standing in front of a brick apartment block, gazing off frame. The photo is printed poster-size, framed in a cheesy faux-antique stock and fitted with a foot like a scaled up drugstore picture frame. A wooden wheelchair ramp behind the figure is echoed by the chunk of two-by-four lumber propping up the white buildout her portrait sits on. The scale is out of whack; the frame stock looks “normal” but the rest doesn’t match. The setup is artificial, too artistic—or it feels too close to home. Marshall uses photography as a vernacular with which to push into intimate, domestic space. The world feels framed. The art of hanging pictures, then: one photo dangles off kilter from the molding on a too-long wire. The shot shows a Cadillac parked on the street, near a tree and a line of treeless yards and houses; the sky is blown out—it is not a “good photo.” The wire is ominous, even evocative of a hanging; the piece recalls the lockets on chains printed in the triptych Heirlooms and Accessories (2002), the background of which depicts a souvenir postcard of a twentieth-century public lynching, which Fred Hampton’s murder practically was. Hampton was assassinated by Chicago police while asleep in his apartment. An FBI informant slipped Hampton barbiturates the night of the raid so he would never wake up again. Later, the Black Panthers took images of the blood-soaked mattress. The Art of Hanging includes a photograph of a framed triple memorial portrait of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Within Marshall’s photo, the portraits’ stamped metal frame is hemmed with wallet photos and clippings, including of the four child victims of the Sixteenth St. Baptist Church bombing of 1963.

Kerry James Marshall, The Art of Hanging Pictures, 2003. Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, March 12–July 3, 2017. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In Marshall’s Souvenir series, black figures with glittery wings hold lonely vigils in their living rooms while the image of that trinity—JFK, RFK, MLK— hovers on their walls in a cloud. In other paintings, life goes on: It’s not just the museum walls at stake. In one gallery are two touching scenes of couples— Slow Dance (1992–93) and Could This Be Love (1992)—set in bedrooms and laced with the melodies of popular songs. These are made around the same time as Marshall’s Garden Project, a major series of exterior scenes of housing projects in Los Angeles and Chicago. The flowers of the wallpaper and the flowers of the gardens that give the housing projects their aspirational names are stenciled like blood on the walls or like an Andy Warhol silkscreen. It’s in this period that Marshall’s work synthesizes his modernisms—the polyvalent flatness of modernist painting and the built idealism of modernist architecture. Marshall sticks realism and historicity between panes of figure and ground. Indeed, the Garden Project codifies the tragedies of Marshall’s subjects within the disappointments of its form. His referential, postmodern medleys uphold a figuration that has been mistaken for cheerfulness, and for which Marshall is sometimes miscategorized as a painter of modern life. (True, his pictures are rendered with a warmth that continues to defy the prevailing cynicism or cannibalism of contemporary painting. The figures are enjoying and tending the gardens of dripping rose stencils.) Other works depict figures inside of homes and businesses. His masterworks De Style (1993) and School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012), populate the interiors of a barbershop and beauty school, respectively, with modern versions of Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533), vanitas and all. Posters decorate the walls and photos are tucked into the frames of heart-shaped mirrors. Yet Marshall’s work vies for a tradition consigned to the museum interior— an “insider” space. At MOCA, the Garden Project is at the heart of the show’s layout. Seven works from the series are hung in one long room, unstretched, unframed, and stuck up with grommets like a painter’s dropcloths and like tapestries lining a medieval hall.

Left: Kerry James Marshall, Self Portrait of the Artist as a Super Model, 1994. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, mounted on board, 25 × 25 in. Center: Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum, 1981. Acrylic on paper, 62 1⁄2 × 52 3⁄8 in. Right: Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self, 1980. Egg tempera on paper, 8 x 6.5 in. Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, March 12–July 3, 2017. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Super Model (1994) bears a background of stenciled roses, like wallpaper that pops to the surface. The artist renders himself with black paint. His lips are rose red, and a blonde, translucent “wig” drapes across his head like bundled brushstrokes. Behind him is the nimbus of a religious icon. At MOCA, this is the leftmost picture on the first wall of the show; the rightmost is Marshall’s originary Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self. The show opens with several of Marshall’s “invisible men,” which is the chronological start of his mature work but also throws into ironic relief a visibility which, especially here on the retrospective’s third stop (after Chicago and New York), is now close to total. Between these two works is the much larger Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum (1981). Of the permutations of the invisible man motif, only Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum shares with Black Artist (Studio View) the sense of a diegetic collage—a picture-in-picture and art-historical pastiche composed not at the level of the painting’s surface but within its mise-en-scene. In the picture, a smaller version of Marshall’s 1980 portrait ornaments a room: portrait of the artist as décor. The painting has the sense of destiny fulfilled. It is a at, knowing piece of art, preordained to the wall, that speaks to the baggy drudgery of domestic life and the vulnerability of breathing things to history’s arrows. Yet Marshall wedges a space between the work and the wall—a space that can’t be seen. Like Black Artist (Studio View), the small picture in Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum contrasts with its immediate context; the black light in the photograph is blown out by the white light of the museum, and the white border of the deep black Portrait of the Artist is set against red wallpaper, hung above the chore, the only other object in the room: a big unplugged green-gray machine. And this whole picture, again, hangs on the museum wall, where it was always meant to go.

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, installation view, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, March 12–July 3, 2017. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Mastry is not only a measure of acceptance from the white Western art system, not only its highest honor—the title of Master (one day, to be Old…). At MOCA, the title wall has the word Mastry in the typeface Marshall developed for his Rhythm Mastr comic strip (1999–ongoing). The word hangs in black space studded with brushy, oral white stars. The title wall is visible from the museum lobby. To the left of the front desk is the MOCA iteration of Kerry James Marshall’s “Mastry”; to the right is the permanent collection. Both exhibitions share a curator in Helen Molesworth. Framed by the rightmost doorway is Jackson Pollock’s Number 1 (1949), an all-over floor-format masterpiece to remind you what Marshall has built on. To master the museum is to gain entry on the museum’s terms, but also to command the museum—the building, the staff, the board, the curator, the collection, and even—to illuminate Marshall’s invisible man—the museum’s publicity arm. Ads are hung on streetlights and pasted to construction sites like pictures in the picture.

Travis Diehl is an editor at X-TRA.