Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection was exhibited at Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA) in Chinatown’s Asian Center from July 31 to September 10, 2021. The collection, organized by artist Kayla Tange and facilitated by LACA Director Hailey Loman, took shape in the months after the tragic murders of six Asian women in Atlanta on March 16, 2021.1 This living archive draws together a social network of artists through materials such as pay stubs, police reports, screenshots, apparel, and oral histories. The collection speaks to anti-Asian violence, starting with the individual bodies and lived experiences of the contributing artists. The project deftly illustrates an archive’s ability to constitute—as well as document—community formations.

The following discussion between Loman, Tange, and Delaney Chieyen Holton developed across seven months of correspondence and two conversations over Zoom (in November and December 2021). The text has been edited for length and clarity.

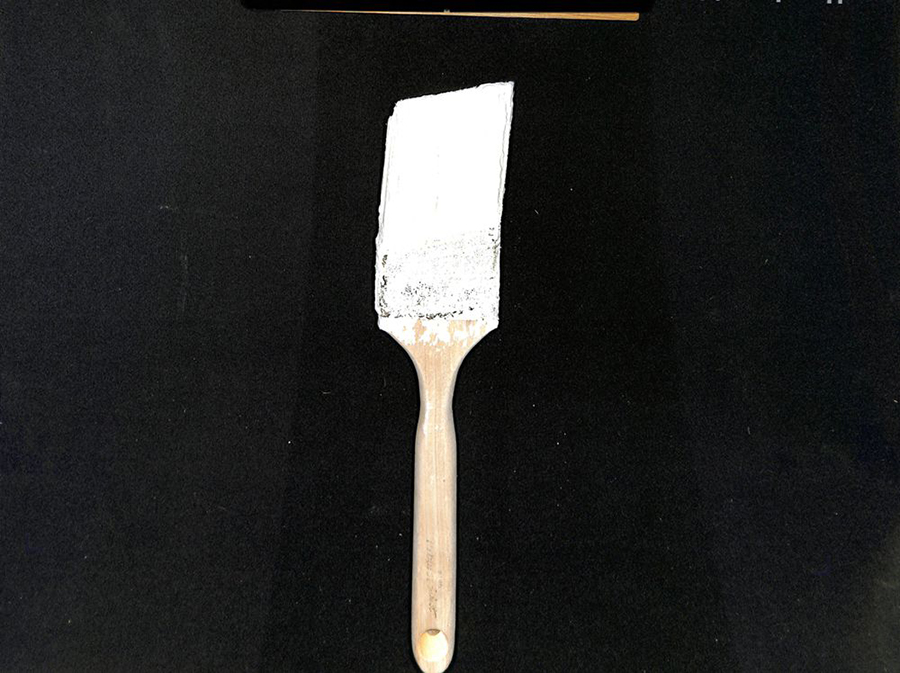

Kayla Tange, Hair extension that was worn and used as a paintbrush while dancing, B55.2-32502, Box 55.2, Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

DELANEY CHIEYEN HOLTON: Hailey, what was your experience of the show?

HAILEY LOMAN: It was quite tender to see the collection while it was up. So many people would pop by and share stories, like, “My grandma was a comfort woman, and she taught me to be aware of how I use my body, and that’s why my body in this space is this way.” Or from an archivist: “I’m working on an archive of sexuality, and I’m always in these spaces that don’t resonate. I want to spend time here.” This is what we wanted to do, to start a collection, exhibit it, and continue growing the community that donates to it and writes about it or writes metadata and descriptions of their material. By opening the show midway through building the collection, it became a living thing. It was really sweet to see it happening in real time. Our initial push was to get materials from a lot of people who use social media or who are of a similar age bracket to us, but it would be great to get more intergenerational materials. More recently, we are planning to work with Kim Ye to archive SWOP LA (Sex Workers Outreach Project LA)’s Making Our Community Safer: The Massage Worker Outreach Program by collecting drawings from a focus group that might happen at LACA.

HOLTON: Were any of those visitors’ responses recorded, or did any contributions to the collection come out of those interactions?

KAYLA TANGE: Hailey sent me the person who talked about their grandmother who was a comfort woman. We would like to do some oral history, because contributors might not have any physical items they can donate, or it might have been so long ago that they didn’t keep anything. In those situations, the oral history is super important.

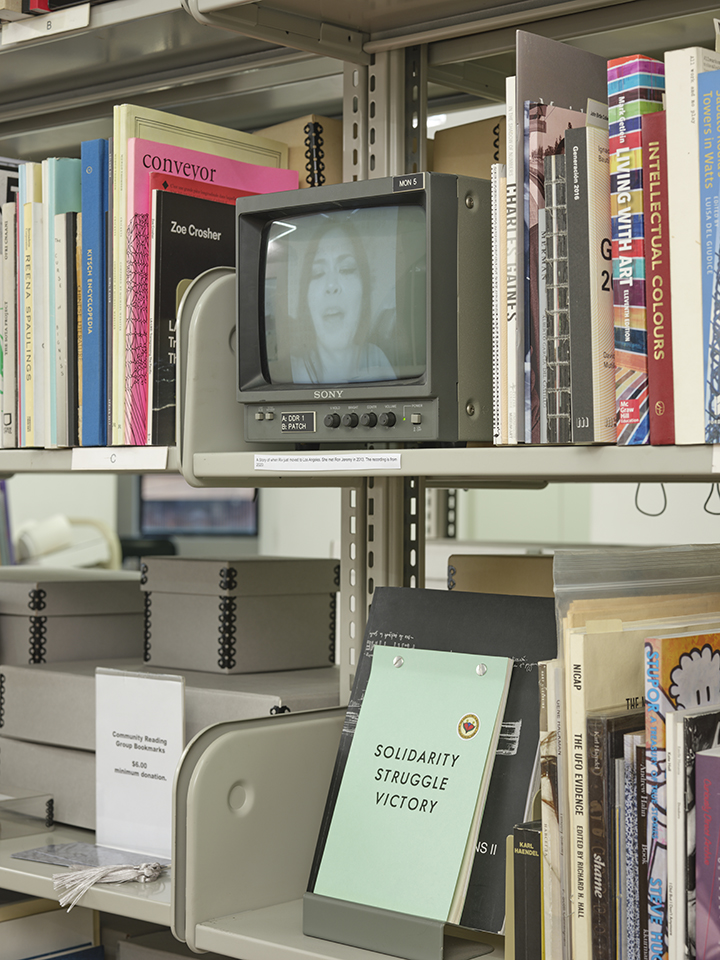

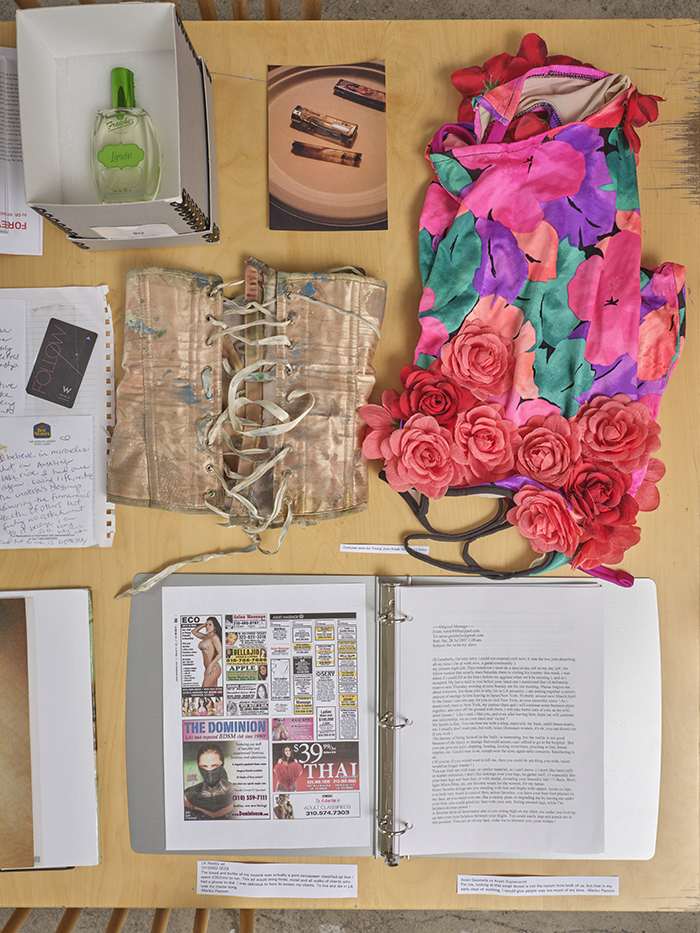

Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, installation view, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, July 31-September 10, 2021. Photo: Alex Delapena.

LOMAN: Right, it’s not always physical stuff from people coming in. How do you archive things that aren’t physical? The history is still valuable. For example, right after [the] Atlanta [murders], Kayla organized an event where she gathered a bunch of people just to get initial responses. Having anecdotal oral histories from those kinds of events alongside the objects offset the ephemeral nature of the topics we were trying to talk about.

TANGE: One oral history contribution came from one of the events we organized in order to create spaces to share stories. Cyber Clown Girls did a fundraiser show, and we donated to a chapter of National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum in Atlanta and to Butterfly, an Asian and migrant sex worker network based in Canada. Before the show, we gathered on Zoom to connect, and one of the dancers told a story of someone throwing a bottle out of their car at her, and she didn’t realize why. She said she heard a muffled mumbling of racial slurs, and then she realized it was after Trump had called COVID-19 the “China virus.” That was part of a recording that was three or four hours long; I cut some of the pieces to make it more digestible. It was a lot to listen to, but people were kind of forced to listen, because it was in the same vitrine as the rest of the items.

Another artist, Riv, shared a story about an experience where the disgraced porn actor Ron Jeremy paid her and her friend $40 to take topless photos of them in his apartment.2 It ended up being a really creepy situation. The way she tells it—moving to LA, needing money, and then getting caught up in the excitement of a possible celebrity interaction—takes us on this funny but horrific journey where, thankfully, in the end, they come out of it safe. In the collection, there are some very traumatic stories, but it’s not all about the tragic lives of sex workers. It isn’t a glamorization of this job either; there are so many different stories that you can’t pigeonhole anyone.

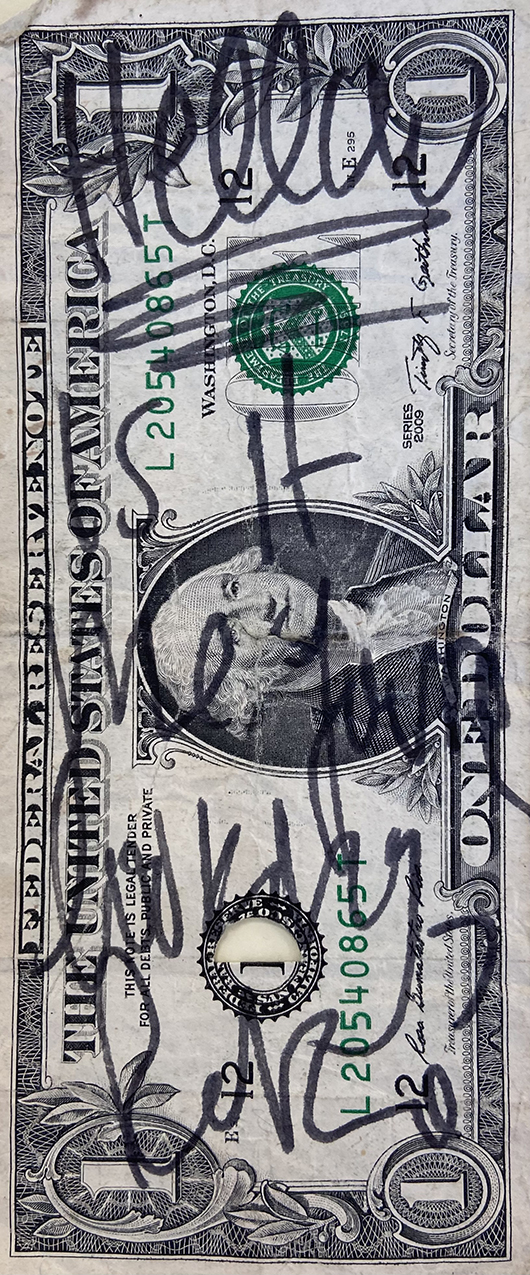

Mariko Passion, Dollar bill with “Hello, is it me you’re looking for?” written on it, B55.2-32660, Box 55.2, Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

LOMAN: There’s a thread that runs through this collection that I struggle to even articulate. It’s the humor of the situation but also that moment when you realize an encounter is going deeply sour. It doesn’t get talked about overtly, but that’s what we were really thinking about: that specific hypersexualized racism. What happened in Atlanta, people didn’t have nuanced language to articulate. And that’s why it sometimes felt like a flat conversation. That’s the story that some of these materials tell, or even the lack of some of these materials tell.

HOLTON: I appreciate the way Private Practices adds diversity to the discourse around AAPI women and sex workers. While I was relieved to see longer histories of Euro-American sexual imperialism in Asia move into wider consciousness last year, the conversation following Atlanta fell flat for me in many ways as well. I needed more than what all those op-eds and Twitter threads could provide, something that could show me and my friends a future rather than a death sentence. With the post-Atlanta discourse in mind, and given the critical vocabulary AAPI women scholars have given us for understanding the simultaneous sharedness and incoherence of our experiences—Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism, Rachel Lee’s The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America, and Laura Hyun Yi Kang’s Compositional Subjects stand out to me as important interventions—I wonder if the hardening of AAPI artists’ and sex workers’ experiences into archival objects complicates the category of objecthood.3 Can you speak to the ways the collection contributes to such meta-narratives around AAPI women and sex workers?

TANGE: I think about that a lot, especially remembering working at various clubs where there was often only me and one other Asian girl. We’d work together to mock customers, like, “Two for one.” Or, “Are we the same person? Am I her? Is she me?” It worked because we were mirroring what was actually said to us, what the customer believed.4 I’m not sure if this was the right way to deal with the racist comments, but somehow it lessened it. In the audio we mentioned before, where dancers were sharing their experiences, there was an awareness that you are turning yourself into an object to make money, that you’re risking becoming a monolith or risking other people viewing you that way, but doing so allows you to live your life how you want. We don’t want to flatten these experiences at all. But maybe that’s just going to happen. There’s almost nothing we can do about that if it’s someone else’s experience or lack of experience with AAPI performance artists. We’re still collecting this stuff; it’s still being worked through in these conversations. But I think the fact that the collection exists makes for a larger group of people for future researchers to find in conversation with each other.

LOMAN: I completely agree. It’s just constantly reworking, coming at it with optimism, hope, and listening. We saw increased violence during the pandemic in Chinatown and post-Atlanta, the added policing.5 We wanted to add to the already existing conversation in Chinatown as well as bring more nuance. It’s something that we’re constantly renegotiating, rethinking, and in conversation about.

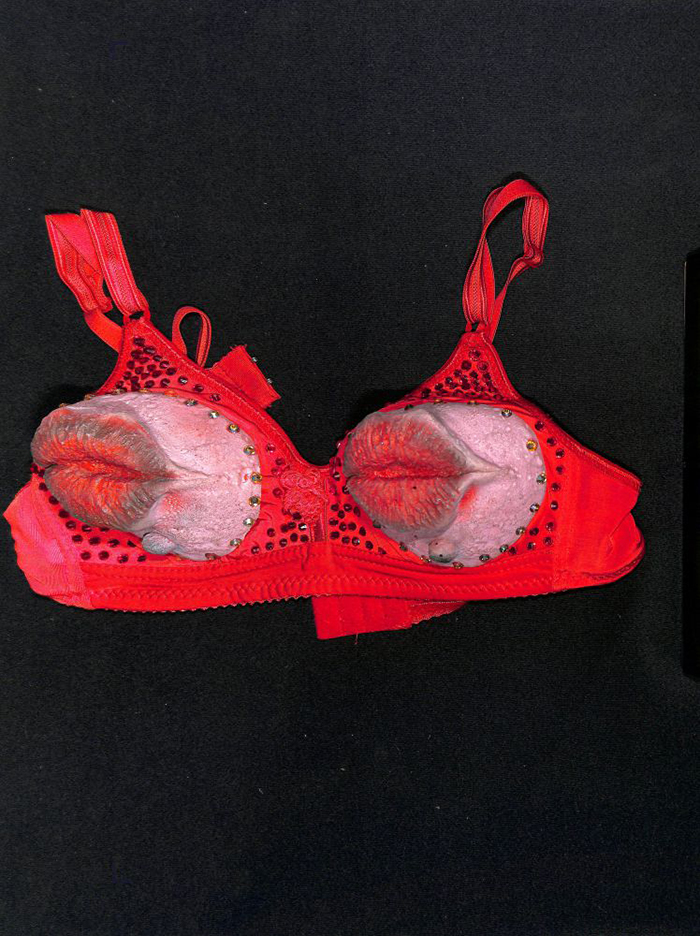

Kayla Tange, Divine Impersonation Bra, B55.2-32500, Box 55.2. Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

HOLTON: On policing, it occurs to me that the archive as a system of knowledge emerged as an apparatus of state control. Traditional institutions of archiving seem like a hazardous space for a collection like Private Practices, which is already so enmeshed in a political matrix of criminalization, hazy labor ethics, and hypersexualized racism. How do contemporary archival practices shift to accommodate materials and histories that have historically been rendered absent from the archive?

LOMAN: At LACA, artists are in control of shaping what they determine is research, what is valuable. I couldn’t have anticipated that Kayla was going to bring things like a paintbrush, a minidress, a bra, confession notes from people, and foam corkboards. But that’s what Kayla said spoke to her work, because she used them in performance pieces. It’s important to us that artists are in control of shaping what enters the archive or best represents their practice. We also kept the metadata and descriptions in the first-person voice. I think to see the word “I” in descriptive metadata is jarring for those ensconced in information studies or archival work. But for LACA, we’re working with people who are alive; their stories have shaped their material. We like people being in control of their own descriptive metadata, because I, as the archivist, would describe something differently. I might say, “This is a costume.” Kayla might say, “No, this is an extension of my skin.” Or “Hailey, this is my outfit, that’s rude.” That’s where there’s some experimentation or where a humor element comes in, and that feels really special about this collection. It’s something I think we’re going to keep doing, having the informational text read in first person.

Brush, B55.1-32497, Box 55.1. Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

HOLTON: I want to ask more about that “I” in the metadata. Sex work so often must happen out of view, for reasons of legality, stigma, and physical safety. In the collection, those uneven textures of disclosure get reproduced, where the first-person voice is under a stage name or might be anonymous. I’m interested in how the particularities of this collection exert pressure on archival practice. What solutions have you found for these cases?

LOMAN: Entering some works into the database, we did come up against questions around stage names. Do we write Mistress Lucy, or do we write Kim Ye? If Kim Ye is okay with both, are they two separate names? Are they two different people? That was something new to encounter for LACA. It’s a good example of how we think archives are truth repositories, and yet, it’s almost like we all have stage names, to different degrees.

We also have a section for archivist notes that’s right under the description. That’s the space to find these little slips; it’s what I love about oral history. You might read, “I interviewed them, and it was a rainy day, and our teacups were clattering.” That kind of note reveals something about their class—they have saucers. Then, you read that it was raining because they were in D.C., and it was winter, and so on. That’s all important information, because it’s in the same spirit that we’re not “objective custodians” of knowledge, as Hilary Jenkinson thought; we’re not neutral, we have our own biases.6 When I put away, for example, Kayla’s shoes for Private Practices, maybe I write, “I have the same shoes at home.” Or, “How come my feet are eight thousand times bigger than Kayla’s?” Those funny quirks are also valuable because they show the folly of an institution or the label of archival material. What makes this fact? Because it’s in an institution? Because we can write whatever we want, and put it into this organization? Is that truth? We’re deciding it together.

TANGE: And same with Mariko. I don’t know Mariko’s real name, but Mariko does sex work as Mariko Passion and is also an artist under that name. Then I’m Kayla, but I’m also Coco Ono, but they’re kind of interchangeable sometimes. Lola Chan is known as Lola Chan. That’s her stage name, and she also has multiple other stage names. At one point she was Kumiko. It’s hard to say at what point you track the names or which name you label an object with. If a name was only used at a club or only as their sex worker name, but maybe they performed as someone else, what do you do then?

LOMAN: It shows the importance of the artist or the contributor playing an active role in shaping their materials and metadata. Everything is cataloged at the item level at LACA, so instead of having a folder that has hundreds of flyers, every individual flyer has its own description and its own entry, organized by the artist’s name. For one, it brings accountability, but it also facilitates browsability. If someone comes in without knowing an artist’s name but wants to see the Private Practices collection, they can gravitate towards that theme or topic, and then they get to know the artist’s work through that process.

Montreal heel, B55.1-32497, Box 55.1. Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

HOLTON: Kayla, since you mentioned the overlapping names used in different settings, could you speak to the overlap between the various settings you work in and the personas you move through? How did you come into performance work?

TANGE: My practice was performance (including stripping) for a decade and a half. Early on, I felt like I didn’t have the space or the money to make larger works. I kind of defaulted to performance, because I could reuse props or have minimal props. I never set out to become a performance artist, but I already danced or did sessions, so this is what was most natural to me, and it was a natural progression to get gigs outside of the club. Performance can be added on to a show as a form of entertainment, but I feel like it was an easy access point for me to even get in.

The overlap between stripping, burlesque, and performance art is the message. Maybe in burlesque, I would lean towards a more satirical, comedic routine that would end in some sort of hasty reveal, like, “Thank you for enduring that really uncomfortable moment, here’s my body.” Whereas with performance art, I would do the same thing, enact the same discomfort, but nothing would come off. Or something would come off, but it was in a different context, so there wouldn’t be people cheering and hooting and hollering. I always felt it was similar.

What’s unique in the collection is the variety of documentation. There are stage names that aren’t necessarily paired with a photo. Lola Chan doesn’t have any photos, just the first shoes that she bought as a “baby stripper.” It’s just the idea that this person existed at some point under this fake name, and these are their first shoes, so it’s contributing to a story.

HOLTON: This brings to mind genealogy practices and the work of tracing one’s ancestry. How is that possible in this case, when there are so many labels for one body? Kayla, I’m curious how the collection comes into conversation with the ancestral healing that you refer to in your practice and the work you do with Sacred Wounds.7 Since Private Practices is a collection of living artists, do you see it establishing a new kind of genealogy, with all of these stage names? I’m eager to see what the collection’s ongoing afterlife looks like, what it does when it’s not on display.

TANGE: I’ve been interested in this since meeting Hailey, but I think Mariko has actively been saving all this material about her work—the blog, flyers that are twenty years old. I feel like she’s been planning on doing this and saving it for someone . . . maybe not kin, but future AAPI sex workers. It’s as if it’s a subconscious urge to save things and show them to people that come after you to know that you existed in the world and you did this work. Before Private Practices, we didn’t all know each other. It’s fascinating to learn more about the other people in the collection . . . and realize that we were all doing this work at the same time, in the same city. In that sense, it can be healing. Even in hindsight, even though a lot of us aren’t even actively doing the work anymore, there is this feeling of camaraderie in knowing that we weren’t alone.

Sex Workers Outreach Project Los Angeles (SWOP LA) Stop and Search Flyer, DO.32928, Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles.

LOMAN: People have already come and asked to access it, not as a display but as an archive. What’s a safe way of showing the material that has the same mood as the exhibition? I’ve been thinking about old VHS tapes that have this warning label that says something about the FBI, a copyright label. I’m asking myself, what can I say each time before someone sees the collection? I want to create a pause before we look. It’s also an operational question. How do we do this quickly, and how do we get people in a place where they’re ready to look at the materials? Not everyone is a scholar in an academic institution. Our community is also the neighborhood around LACA—Chinatown. We see what our community at LACA needs and try to make that possible. So, this process of collecting and working with people, displaying it, and then continuing to actively collect is a template that we’re going to continue at LACA.

TANGE: I’ve been saving all my shoes since probably 2010, maybe before. So, I have something like two dozen pairs of heels. Some are pretty beat up. I felt comfortable giving these half-retired things to LACA because it’s not like once you turn it over you can never have it back. If my house burns down or if something else happens, there are some pieces left at LACA. The process is not exploitative, as if you no longer exist and now this institution has control over your collection of bras or whatever.

LOMAN: For LACA, we’ve thought about how we can be a physical resource. If there’s a leak, a flood, a fire, how do we do archival work without going in and plundering someone’s goods? How do we also be a place that takes physical care of the material? I always joke about certain post-custodial collections, you go in, you scan, you leave, and then their house burns down, and it’s not your problem. You’re not paying their rent! What’s it like to pay the rent and keep people’s stuff safe?

HOLTON: I feel like that highlights the role of archives in nurturing their public futurities. The objects’ existence together in the archive shows us the potential outlines of a community. What is at stake in the disintegration of these objects? I’m interested in the durability of the collection to retain its references and meaning over time. A text-based work or photograph might remain intelligible for quite a while because it’s a form that we already understand to last through time. But perhaps garments or shoes are more precarious as they drift away from the performances they were originally involved in.

TANGE: For many erotic artists, these relics are made for one night and one show, for a quick expression. A lot of times there’s no video recording. There might be a text or some photos, but with performance itself, at least for me, I started feeling that it has a limited time. I’ve injured myself so many times from doing tricks that extended already weak areas of my body or wearing hard plastic heels for so many years. In terms of durability, some things are going to disintegrate in the next twenty years. Probably my lip bra, that thing is made of foam. Material breakdowns will definitely happen. Obviously, there are performers that work for decades and decades, but you’re very aware of the limitations as the years go by. When we aren’t alive anymore, this collection will determine how we’re going to be viewed. I think it’s important to keep these works together in this context. Something happens when seeing all of it together. From my perspective, it becomes less fetishized.

Kayla Tange, Defining Boundaries, performance, Human Resources, Los Angeles, December 20, 2018. Photos: Kevin Kane.

LOMAN: It’s amazing when folks’ ephemera come together in a way that you can really start to see, instead of an isolated thought, real collective yearning, longing, moods, and perspectives. One that was moving for me was the pervasiveness of misogyny, which can sometimes be subtle. For example, observing in the ephemera the nuance of how clients take up space and attempt to dominate or control language was a thread throughout the collection. It unites perspectives and shows the vastness of shared experience. As the collection continues to build, we can start to track things like generations and age groups and identify patterns across vastly different geographies. Seeing someone in Toronto and someone in Los Angeles’ Chinatown reporting similar experiences offers a bigger picture to think about.

TANGE: Another aspect of that vastness is that there are more people that want to be involved. I think what’s interesting is that there are people in the collection that are still actively working in the industry. There are people that have gone on to only do performance art. There are people that have retired completely. There are people that have dabbled in sex work very briefly. For some, it’s not part of their identity whatsoever. That was another conversation we had: What does it mean to tag “AAPI”? What does it mean to tag “sex worker”? And I think now we are expanding the language to encompass AAPI artists working in sexuality.

HOLTON: That language strikes me as a way of offering protection through ambiguity, a way the collection shows care to its contributors. I’m thinking through something that you said in your talk at the Fowler Museum, Kayla. You said that when your vulnerability as a performer has been exhausted, the artist also has to have a practice of defining boundaries for themselves.8 Do you see resonance between the culture around consent in sex work and performance settings and that in institutional settings?

Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, installation view, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, July 31-September 10, 2021. Photo: Alex Delapena.

TANGE: When I did my work Defining Boundaries (2018), I was trying to define my own way of art making. I was tired of dancing, and I was doing it because I still needed a job that was relatively flexible. I still kept a lot of things that the old customers gave me. I kept all the confession notes from my performance Confession Box (2015–16). That’s why a lot of the stuff at LACA still exists. Even though I was tired, and things became too much, it didn’t necessarily mean that I didn’t still see value in those objects or experiences. I think that’s how Mariko sees her blog. All that stuff happened, and I’m in a different place right now, and I’m working on healing. Even if you don’t identify the same way anymore, you don’t want to believe that it was in vain. Maybe that is what I needed to process at that time to get through it. When building the collection, I was amazed that people trusted us to have these items, trusted us with these stories, and actually wanted to share them in this space, because they knew that we were caring about what they went through.

LOMAN: I’ve been writing on consent and what it means at LACA. How can we draft deeds of gift that account for the complexity of consent? We choose to do consent forms and deeds of gift at LACA because I, as the director, find them compelling, but not every archive does. Consent forms are a way to slow down and talk about what an archive is and the implications of donating. On the other hand, what about the archive’s consent? It’s not a popular archival conversation to talk about how an archival institution might have served as someone’s storage facility, paying rent and keeping their material safe for twenty years. But I think it is valuable to discuss metadata practices and consent forms, because they are a chance to disrupt presumptions we can make as archival donors.

This collection is different, because this group of people know consent is a fallacy, they face it every day. But I still talked with Kayla a lot about privacy, consent, and contributors’ rights. If an object is listed under a stage name, that’s a whole different kind of legality. Will they still have rights if it’s under a name or gender that’s not on their birth certificate? Will you still have rights if you change your name, and we’re holding all your proof at the archive? It’s a really vulnerable exchange. So much of donating is like writing your will. We’re thinking of worst-case scenarios in the end.

TANGE: There was one scenario where I had this customer for over ten years. Much of our time together was spent sharing meals and doing various fetish photoshoots. The photos are amazing in terms of being a time capsule of what two people went through for a decade, and how they developed a really good friendship. I asked him if we could show these photos, and his response was, “Not until I’m dead.” So, I told Hailey, “I’d like to put them somewhere, but maybe put them away until they get opened on a certain date, but not publicly.”

Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, installation view, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, July 31-September 10, 2021. Photo: Alex Delapena.

LOMAN: Yeah, and in such a case, we have to be responsible to say that maybe we can’t take these materials on. Archives, especially community archives, need to be aware that sometimes we can’t actually handle a request like that; so many people have keys to LACA. It is an interesting conundrum when we need to ethically say we don’t have the facilities; it’s not in the archivists’ power to properly house this. It’s part of me trying to be accountable.

Another aspect to consider is how we frame our archival work. Thinking about the phrase “Private Practice,” I find it off-putting when people say things like, “This collection is amplifying hidden voices.” Those voices have been here; we’ve been here. There’s an article by Yusef Omowale called “We Already Are” about the use of the term “community archives” as a supposedly new genre and how we’ve actually always been doing this work; it’s just that institutions have decided now to acknowledge these materials.9 Maybe, in that way, it’s private, but it’s not new. And maybe we’re just an archive, not a “community archive.”

TANGE: Hailey came up with the name Private Practices.

LOMAN: It was pulled from your Confession Box piece.

TANGE: The use of the private was pretty important in the way we reached out to contributors. Some people heard about it from a friend. It was kind of word of mouth. Maybe it felt safer to share because people either knew someone organizing it or they knew they wouldn’t twist the story. It’s the same as giving different answers to someone interviewing me who I feel understands where I’m coming from, as opposed to some person that has no idea at all. When there’s no clear framework, and then the questions are different, I’m going to give different answers.

HOLTON: In that way, the collection captures some kind of information about the social networks and community connections that are already in place. If you were to think about building out that network into the future, is there a message you’d like to give to other current and future AAPI artists or sex workers?

Private Practices: AAPI Artist and Sex Worker Collection, installation view, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, July 31-September 10, 2021. Photo: Alex Delapena.

TANGE: I was thinking a lot about this recently because when Mariko was writing the blog, we were both working in similar industries, but we didn’t know each other. I was thinking about how important community and support systems are. I did have some people that I felt like I could trust and who introduced me to people that I felt I could be supported by. It’s already hard to do that work, it can get a little dark, you know? There is so much importance in having a long-term community-outreach situation. I didn’t always know how to go about finding the right fit, but I’m grateful that a cry for help moved somebody to introduce me to the people that I needed to talk to. We want the collection to show, forty or fifty years from now, when we’re not here anymore, that these people—this community—existed.

Delaney Chieyen Holton is a writer and curator based in the San Francisco Bay Area pursuing a PhD in Art History at Stanford University.

Hailey Loman is a multidisciplinary artist working in sculpture, installation, and performance. She is the cofounder and director of Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA), an artist-run archive and noncirculating library in which contemporary creative processes are recorded and preserved. She founded Autonomous Oral History Group (AOHG), a cooperative that examines the ethics that operate in leadership roles. The group collects interviews, recordings, transcriptions, and ephemera during the process and assembles and makes them accessible as an oral history collection.

Kayla Tange is a Los Angeles-based artist born in South Korea and adopted by a Japanese American family. Psychic boundaries, sexuality, and permanence are recurring themes in her work. She is the coproducer of Sacred Wounds, an online show focused on ritual, subverting cultural stereotypes, and ancestral healing for Asian performers. She is also part of the Korean diaspora collectives Hwa Records and Han Diaspora Group. Tange is known as “the erotic conceptualist” under the performer name Coco Ono. As Ono, she explores emotional and societal confines, often using dark humor. Coupling her experiences with a recalibration of her own narrative, she creates her work to facilitate meaningful dialogue around death, mutation, and our need for connection and belonging.