A Critical Reflection of a Particular Physical Location1

With the exception of a permanent work on the cornerstone facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Grand Avenue building (The Artist’s Museum: MMX of 2010, which was commissioned for The Artist’s Museum exhibition) the work of Los Angeles-based artist John Knight is difficult to see in his hometown. During Printed Matter’s L.A. Art Book Fair, London’s Cabinet Gallery hosted an intimately scaled exhibition of Knight’s works in the airy architectural space of R.M. Schindler’s 1936 Fitzpatrick-Leland House on the peak of Mulholland Drive and Laurel Canyon Boulevard. Spanning 40 years, the material in the show captured the elusive and temporal nature of Knight’s work, specifically his interest in challenging the definition of the art object by its displacement into the space of publications and ephemera. The variety of works rarely seen together—editions, unique pieces, photographic documentation, maquettes, journals, and exhibition catalogs— addressed Knight’s consistent conceptual concerns: the circulation and reception of exhibition practices, art’s actual socio-political engagement (as in his commission for the MAK Center for Art and Architecture’s public art project How Many Billboards? in 2010), and, as is demonstrated aptly here in the Fitzpatrick-Leland House, the confluence of architecture and design.

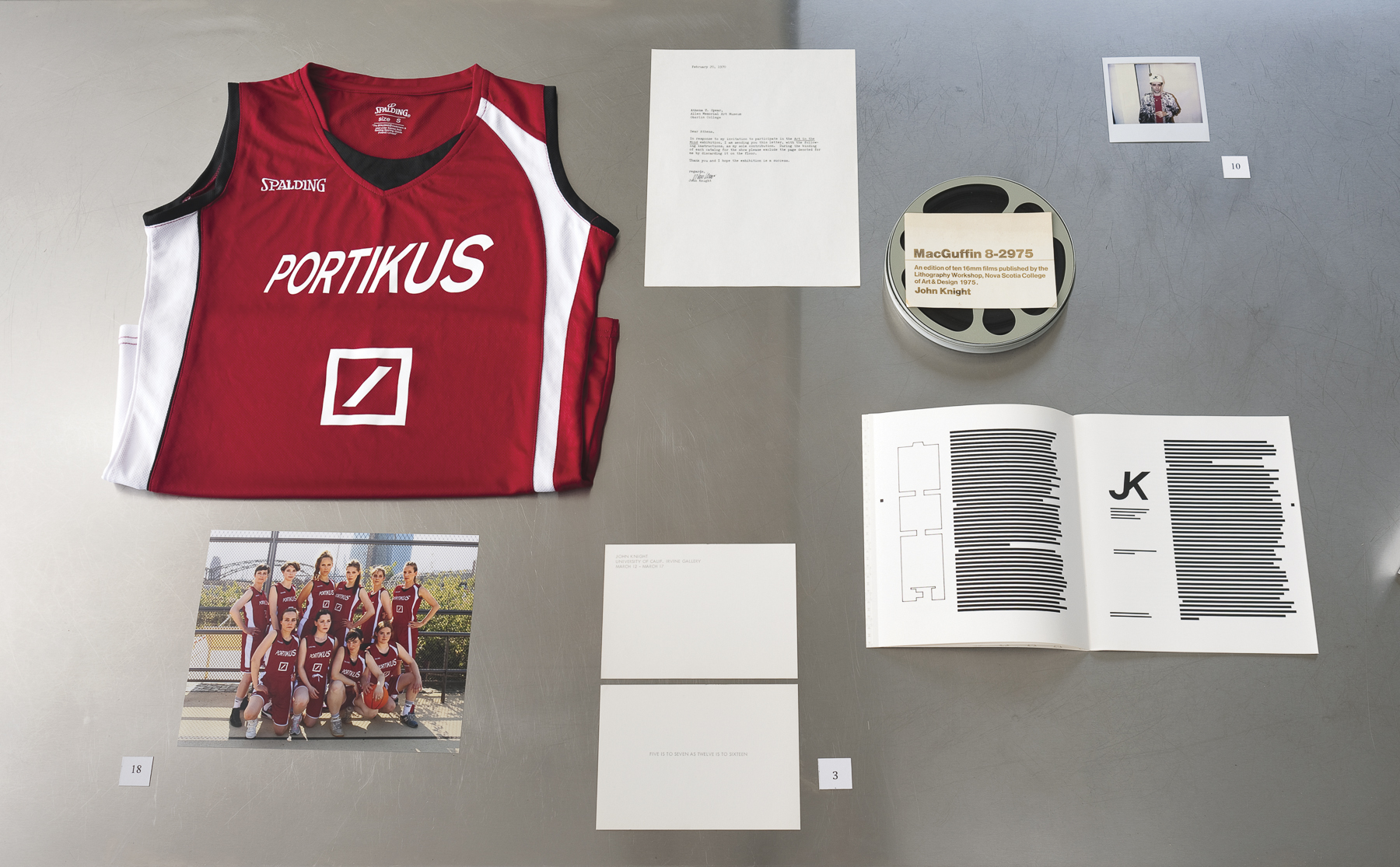

John Knight, Fitzpatrick-Leland House, Los Angeles, installation view, February 1–5, 2014. Selection of John Knight publications and exhibition invitation cards. Courtesy of the artist and Cabinet Gallery, London.

Located in an archetypal mid-century Modernist house, the show was organized to complement the aesthetics of a display home, with a few elements of domestic functionality intact.2 Under these unfortunately brief and oddly covert circumstances, several of Knight’s projects were collect- ed or recreated. Two large vitrines with ephemera and larger works were arranged around the living room and basement of the house. Notable were his serial exhibition catalogs that utilize the same 9-by-8 inch format and design in all ten iterations, with the exception of two that retained the specific style of their publishing institution. Forming a significant part of his oeuvre, the catalogs represent Knight’s persistent displacement of conventional exhibition practices into the supposedly secondary textual devices exhibitions typically generate: announcement cards, posters, and press releases. As rarified objects in and of themselves, deliberately lacking ISBN numbers, the publications are what Knight calls “exaggerated and hyper-designed sites of agitation that attempt to insist on the utility rather than the autonomy of the work.”3 Due to the fact that his work is always specifically commissioned for a particular site, referred to as in situ by most artists of his generation, the catalogs and the ephemera become hybrids—a combination of conceptual displacements that reveal the source of the exhibition concepts but still function in their conventional sense.

Many pieces in the Fitzpatrick-Leland exhibition are the sole documentation of a project, such as a Polaroid of the late director of American Fine Arts, New York, Colin de Land, with cigarette in hand. In the photograph, de Land wears a white baseball cap with Knight’s branded initials (JK) emblazoned on it, from a unique edition the artist created for Art Basel in 1995. (Knight created a logotype with his initials for Documenta 7, in 1982, where he placed eight identical wall reliefs on every stairwell landing.4 He continues to use the branded logo in his publications and other works.)

In the middle of the living room, a white mountain bike displayed De Campagne (1993), a plexiglass bicycle bell with a stork engraved on the top whose legs are crossed to form, again, Knight’s branded initials. When rung, De Campagne makes an unexpected metallic sound, like that of a croaking frog. Commissioned for Stroom Den Haag, Netherlands, the piece was created as an exchange program in which museum visitors could trade their working bicycle bells in exchange for one of Knight’s “frog bells” (as visitors referred to them). The new bicycle bells were also shipped from the Netherlands and distributed in the otherwise internationally embargoed Havana, Cuba. Identity Capital, exhibited in the Fitzpatrick-Leland basement, took the form of a floral arrangement borrowed from a neighborhood restaurant. Left behind in the place of the borrowed bouquet is a card noting the new location of the work. The original Identity Capital was exhibited at American Fine Arts, New York, in 1998.

Knight’s Chile (1989), a travel poster wrapped over cardboard in the shape of a pentagon, leans against a high windowpane. The piece is a rare artist’s study for what became Cold Cuts at the Espai d’art contemporani de Castelló, Spain (EACC), in 2008. In that exhibition, a series of large-scale pentagonal-shaped vinyl decals were installed covering the floor and walls. Many of the decals sported images from tourism advertising and exotic food photography from locations associated with American imperialism since the 1950s. But the Cold Cuts exhibition was only a graphically loud and overwrought teaser for Knight’s ex situ exhibition, which was— following Knight’s displacement logic—the Cold Cuts catalog. This artist’s book, a “take-away” Cold Cuts, is full of recipes for regional dishes from locations associated with American military actions, such as Vietnam, El Salvador, and in the case of the study on display here, Chile. Each chapter, titled according to the Pentagon’s code name for the corresponding military operation, also contains documentary photographs of events associated with the action and quotes from American governmental officials justifying the intervention. The actual exhibition of Cold Cuts reveals nothing except the bombast of a design “identity,” in this case that of the Pentagon. Next to Worldebt (1998), an installation of oversize credit cards of all the countries in debt to the World Bank, Cold Cuts is one of Knight’s most aggressive yet aesthetically rich pieces. Cold Cuts inverts what Knight refers to as the “established registers of primary and secondary text…to treat the ‘exhibition problem’ as propaganda and the document as the primary site of reception.”5

John Knight, Fitzpatrick-Leland House, Los Angeles, installation view, February 1–5, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Cabinet Gallery, London.

In his recent exhibitions in London, Frankfurt, and Berlin, in 2012 and 2013, Knight returned to the site of architecture as the source for critiqu- ing historicity and social institutions. In the show (and work) titled Quiet Quality (1974), at Cabinet Gallery in London, a wall plaque with text from a newspaper advertisement appeared adjacent to an electric blanket folded on the floor to the proportions of a single bed and plugged into the wall. The text of Quiet Quality references Crown Pointe, a decidedly conservative suburban housing development in Orange County, on the outskirts of Los Angeles. The advertisement touts Crown Pointe as a private haven from the urban fabric of Los Angeles County and secluded from the diversity of its population. By deploying the rhetoric of advertising, Quiet Quality addresses sites of desire in the consumer marketplace, with all their underlying socially exclusive implications.

In May 2013, at Portikus, in Frankfurt am Main, Knight once again made one of his exhibition catalogs the central aspect of his show. Presented in the form of an interview between Knight and art historian André Rottmann, the exhibition was comprised of oversized vinyl wall panels of catalog pages in which Knight and Rottmann discuss Knight’s influences, relationships, and processes over his 40-year career. This time, in a reversal of ephemeral specificity, the viewer could only read the catalog text in the space, shifting the focus of what Rottmann calls in the interview “certain elements of architecture that are habitually not emphasized or addressed through display conventions and material objects.”6 Further, the installation as interview itself comes to represent Knight’s projects through purely dialogical means, once again blurring the distinctions between history, architecture, and design. In June 2013, at MD72, in Berlin, Knight removed the worn wooden panels from the roof of the former MD72 gallery space in the hip neighborhood of Berlin Mitte and installed them on the pristine white walls of their new gallery space, creating a kind of low mantel across the gallery walls. The dislocated roof marked a transference of the exhibition history from the old gallery space to the new site through its architectural remnants.

By expanding the written page to fill the walls of the Portikus galleries, Knight’s work was literally the text, making the conversation a kind of nod to the retrospective—or as close as Knight might allow. By inverting the text into the so-called object of the work, Knight asserted the importance of his oeuvre of catalogs as the work rather than as secondary sites of reception. In this way, Knight succeeded in finally distorting the “exhibition problem” into the full spectrum of the discursive, since at this point a catalog has been an exhibition and an exhibition has been a catalog. Knight renders visible the invisible aspects of exhibition7 (in contrast to Rottmann’s claim that Knight’s art is a “montage of negations”8) and he utilizes design and architecture to make visible the problem of autonomous objects in the spaces where those objects proliferate. Throughout his practice, Knight presents a deliberate, reflexive critique of socio-political issues that operate within and around the circulation and aesthetic conventions of art exhibitions.

Considering that Knight has exhibited in Europe three times over the last two years, the brevity and limited publicity of his five-day exhibition at the Fitzpatrick-Leland House underscored his lack of visibility in Los Angeles, whether purposeful or not. Seeing the complexity of multiple works on exhibition in one site, albeit fleetingly, was a welcome occasion for those of us who caught it.

Gladys-Katherina Hernando is an independent curator and a curatorial assistant at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. She graduated from the University of Southern California and Otis College of Art and Design. Her writing has appeared in the Art Book Review, East of Borneo, San Francisco Arts Quarterly, and Sensitive Boys.