Introduction: The Punk Platform

Halfway through 1984’s Knife Boxing, Johanna Went interrupts her incessant frenzied bopping to thrust her hands into a crudely made body part—half-buttocks, half-vagina—suspended from the roof of Club Lingerie.1 A vicious viscous excremental substance seeps down her arm. She brings her face close and sucks the stuff into her mouth before hauling out a giant goo-covered tampon that she aggressively flings at the audience. Some cringe, others laugh. Quickly she pulls on a costume, a huge mask-headed apron covered in sex doll heads, all the while screaming her unique tongue, a babble from Hell channeled through Lolita-cum-Medea. Screeching tape loops accompany her, along with a blaring saxophone and a loud percussive racket emanating from a woman drumming on found objects.2 A monstrous vagina appears stage right. Went extracts more tampons, heaving each into the mesmerized mosh pit. Completely at one with her, the audience starts hurling these back in a game of volleyball gone mad. After all, this show was held to coincide with the Los Angeles Olympics. Much art programming accompanied that event, but Went was not part of the roster. Instead, she held her own celebration of sports, on the stage of a punk club, flanked by headless stockinette figures replete with genitalia parodying the elegant cast metal kouroi made by Robert Graham to decorate the official Olympic stadiums.

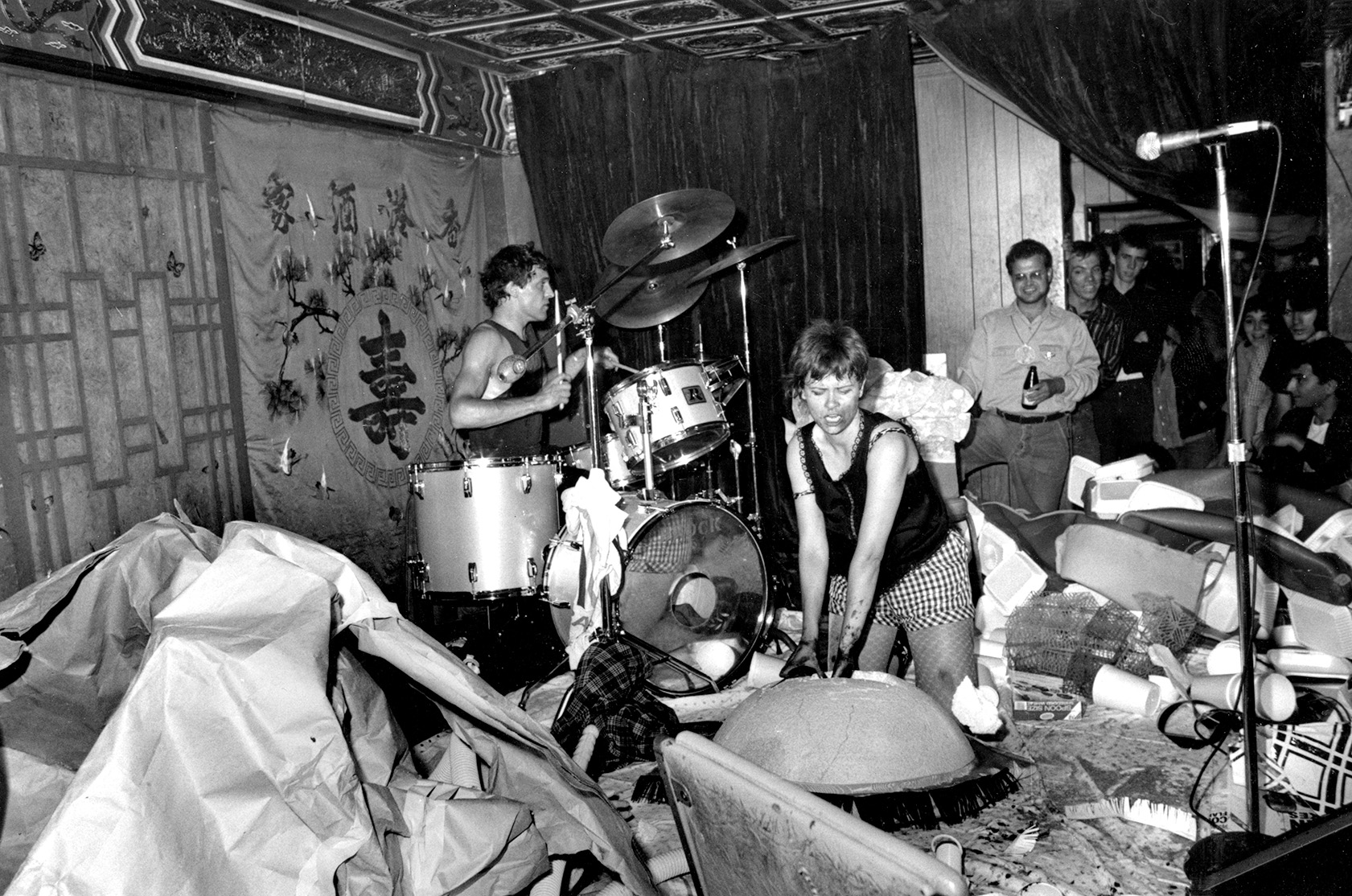

Johanna Went, Knife Boxing, July 27, 1984. Performance at Club Lingerie, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Lynda Burdick.

Suddenly Went disrupts the flow of tampons, drags down the effigies, and flings them at the audience, but not before sucking on one’s dick. An evil secretion oozes, again, and Went laps it up. Tampons and effigies rocket between audience and performer at a rapid clip. Went is almost knocked down. Abandoning the dolls-head costume she picks up a skull-ringed cardboard wheel. Pulling the bones off, she hits these into the audience, using a plastic femur as a bat. Next comes the “watersports,” when Went dons a crude coat made of foam and map pieces before hacking into a dummy made from a stuffed wetsuit.3 Guts spill everywhere, real meat guts, and she starts spinning in circles, “just like in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.”4 She dons a new outfit—an elaborately made Statue of Liberty, its torch gushing a river of red fire. Seizing a skinned goat’s head trailing an extraterrestrial tail, Went’s hand starts pumping. The head writhes. Blood spews from its maw, spraying both the performer and the front row, though her intention is not to deliberately smear them.5 In any case, those up front are her most ardent fans, and they know the drill. The music shifts sharply into a patriotic anthem, as Went whirls with her blood-gushing alien baby. Covered in muck and now deeply sunk in a trance, she drops the still pumping head and wraps herself in a plastic sheet. Letting this too fall into the piles of debris filling the stage, she moves exhaustedly. Suddenly, a spectator grabs at her ankle. She kicks back and falls awkwardly, literally collapsing into the mess she has made with her excremental, carnivalesque frenzy. Tampons and effigies fly, but, for the performer at least, the show is done.

Between 1977 and 1987, Went performed nearly 200 shows, mostly in punk clubs. She says, “Clubs are the perfect place for spontaneous work because all the audience is drunk. Working in clubs removes the preciousness. And you can leave a mess on stage, drunk people don’t care about getting blood on their jackets.”6 For Went, the punk scene was a revelation, encouraging performers of all stripes to experiment in ways not possible within self-designated art spaces, where habits of spectatorship are fixed and aesthetic provocations rarely inspire real antagonism. By contrast, punk audiences were willing and eager, even longing, to engage in fights with performers. The performing duo known as the Kipper Kids was once dragged off stage by bouncers before the audience killed them.7 Even more than its lack of preciousness, first wave L.A. punk was marked by a unique inclusivity embracing suburban kids, camp performers, Hollywood players, and fashion designers, all rubbing shoulders with artists and art students like future luminaries Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy.

As Mark Wheaton, Went’s long-term musical collaborator says, “There wasn’t really a punk scene. It was more like a broad underground composed of many different interlocking groups and interests, though at its core there were really only a few hundred people.”8 And these people moved freely from one medium to another. Nothing congealed for long. Tomata du Plenty, a member of the gay glam theatre group known as The Cockettes, later became front man for The Screamers, one of L.A.’s seminal punk bands. A Seattle-based offshoot of The Cockettes, known as Ze Whiz Kids, often opened for proto-punk musical headliners like Alice Cooper and the New York Dolls when these bands played in Washington State.

Johanna Went and Brock Wheaton (left) performing at the Hong Kong Café, Los Angeles, 1980. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Alan Peak.

Of course, punk was not an exclusively West-Coast phenomenon, nor was the crossover between punk and performance art unique to the area. But, with its distance from centers of cultural authority, Los Angeles provided a particularly auspicious environment in which the two could mix. Self-identified performance artists who crossed between art and punk in the late 1970s and early 1980s include the Kipper Kids, Bob & Bob, Fat & Fucked up, Ron Athey (who performed with Christian Death), and Phranc, who played with Catholic Discipline and Nervous Gender. Vaginal Davis, a queercore progenitor, founded a concept band called The Afro Sisters fronted by Alice Bag of The Bags, while “Asco co-founder Willie Herrón led the Chicano punk rock group Los Illegals and helped found…the first venue for punk concerts in East LA.”9

Went entered this scene as an outsider who had to beg the owner of the Hong Kong Café to grant her first club gig. Despite her rawness, Went was already a highly experienced performer, having traveled the United States and Europe performing guerilla theater in streets, coffee shops, and playhouses with Tom Murrin, aka Alien Comic. However, it was not until she collaborated with musicians in punk clubs that she found her audience, and they found her. The Hong Kong Café show made Went a star. Even in that heterogeneous world, no one had seen anything like it; but the audience was open-minded, loved her energy, and appreciated her willingness to improvise and experiment on the spot. By 1980, she had been interviewed by Slash magazine, the mouthpiece of the punk scene, and was playing gigs in the great clubs, such as Club Lingerie, Mabuhay Gardens, and The Whiskey.

The Johanna Went Experience

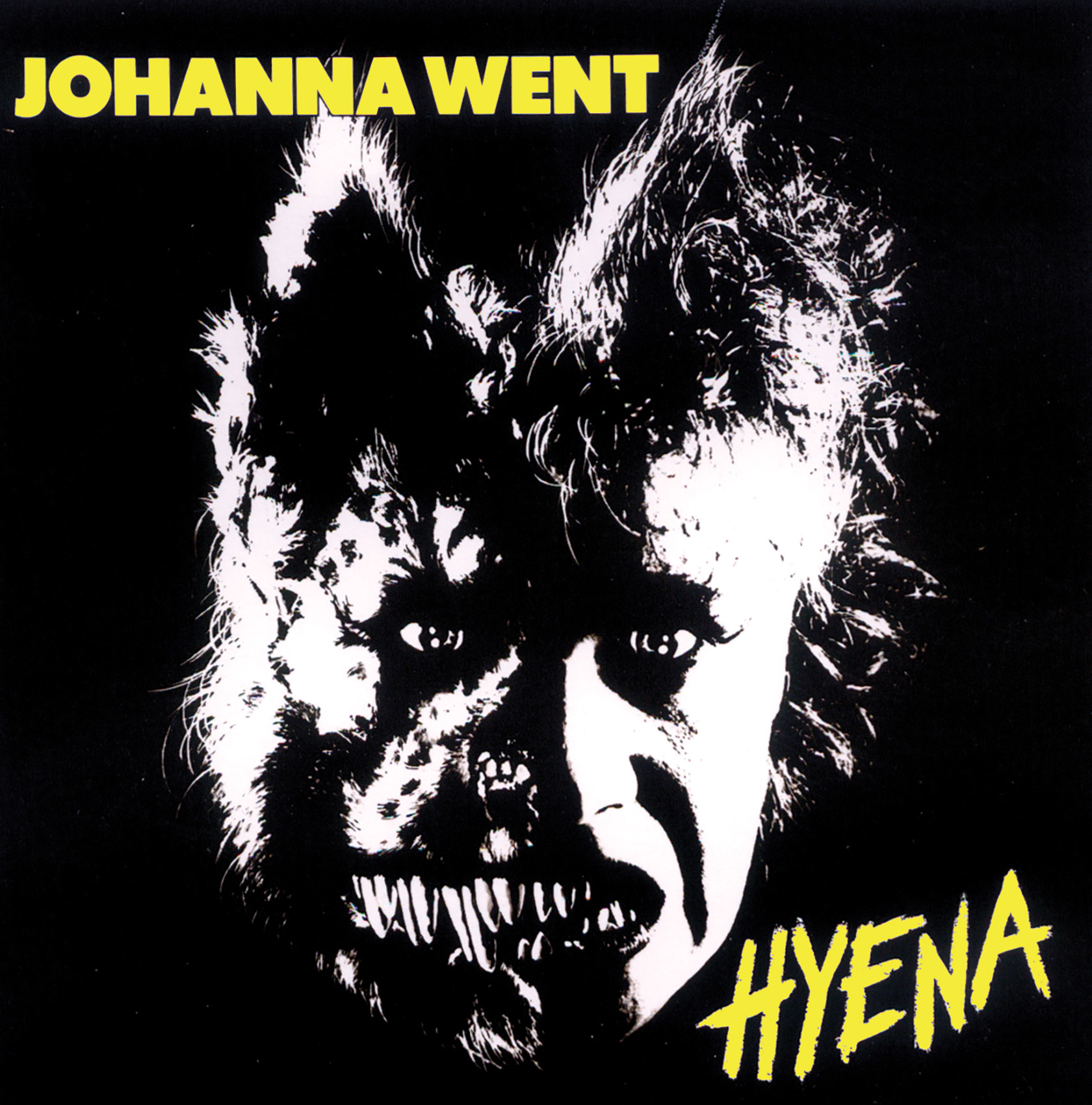

Went’s shows are composed of four main strands: collaboration with musicians, her own contribution as vocalist-performer, an intensely focused interaction with the audience, and the vast array of costumes, sets, props and other objects with which she adorned the stage and herself. First, the sound. Though Went worked with numerous noisemakers from the punk scene, such as Robyn Ryan, Greg Burk, and the legendary percussionist z’ev, her longest-term collaborator is Mark Wheaton, who played experimental tape loops and synthesizer and engineered all her recordings. Until his death in the mid-eighties, the drummer Brock Wheaton, Mark’s brother, often accompanied them. This collaboration, which began in early 1980, at Went’s request, lasted until 2007 and included over 100 shows, plus a series of recordings, including the LP Hyena and the single Slave from Beyond the Grave. These and other audio recordings engineered by Wheaton have been collected on the bonus CD accompanying the DVD Johanna Went: Club Years, 1977–1987, the only commercially available source of recordings of Went’s work.10 In both recordings and live performances, the music is loud and cacophonous. “It was something like music but it was also something like a roar. I don’t necessarily remember it having a beat but it may have because I remember it as being very sexy. Sex is something that usually moves to a beat. Sometimes so slow you don’t even know it has a beat, sometimes a steady muffled pulse, other times a flailing, grinding, pounding machine-like syncopation, but always a beat.”11 Accompanying this cacophonous roar, Went’s vocals are an uncategorizable mix of sound and word fragments muttered and babbled, indecipherable screams, and hypnotic chants, all emitted at a high-octane pitch that completely meshes with the musicians’ noise. The overarching effect is a punk-version of virtuoso jazz, though, as punks, they naturally eschew the concept of artistic expertise. Indeed, Went declares, “A performance artist must never rely on skills that could be construed as actual talent.”12

Johanna Went, Hyena, 1982. LP, Poshboy Records, produced by Mark Wheaton and Johanna Went, included in Johanna Went: Club Years 1977–1987, DVD (Soleilmoon Recordings, 2007). Cover design: Diane Zincavage. Photo: Ed Colver. Courtesy of the artist.

Even more, Went shuns any notion of rehearsal or formal preparation before a show. “You should not rehearse, ever. Or script the formal portions. The aim of a performance is to surprise people, yourself as well as the audience. Whatever inspirations lock onto me like a brain spider, those are as profound as anything scripted. I trust.”13 This is why it takes a special kind of musician to work with her, for she insists that they be as improvisational and interactive as she, ceding mastery and intentional control for the gift of creating interactions with herself, with the other musicians, and with the audience.

Went’s attitude here recalls Allan Kaprow’s focus on un-art. In In Other Los Angeleses: Multicentric Performance Art, Meiling Cheng argues that, in addition to the profound influence of feminist art, Los Angeles performance art of the 1970s and 1980s was deeply influenced by Kaprow’s distinction between Art-art—which assumes a condition of spiritual, technical and conceptual rarity—and un-art—which has not yet been accepted as art.14 Kaprow’s overall project involved a pedagogical mission aimed at the “education of the un-artist.”15 Here, already formed artists were trained to disavow Art and re-orient themselves toward un-art, by forgoing any reference to being an artist in the first place. With her refusal of skill, planning, and mastery, Went is a natural un-artist.

Went calls her performances “wet work”—not because of their moist components but for their “unfinished” qualities. Cheng suggests we see them as examples of the grotesque, after the literary critic and theorist of the carnivalesque, Mikhail Bakhtin.16 According to Bakhtin, the grotesque entails a downward movement toward degradation, reveling in the functions of the lower body—the belly, reproductive organs, and orifices of elimination. Entrails, copulation, defecation, and digestion each play a role. “Degradation digs a bodily grave for a new birth; it has not only a destructive, negative aspect, but also a regenerating one.”17 Cheng’s point is apposite, for despite the proliferation of crude, grotesque, and even scatological elements, Went’s performances exhilarate and regenerate, leaving audiences with a heightened, even ecstatic sense of being; a kind of Burkean sublime, produced not by the re-presentation of a simulated life-threatening event—like a horror movie—but rather through her highly incongruous mix of materials, images, actions, and sounds often focused on the lower organs. Artist and writer Mark Bloch describes the experience:

I was bordering on a frenzied anti-aesthetic love psychosis at the time, that’s how I remember Johanna Went in L.A… The experience I had that night bordered on religious. It was beyond subversion; it was madness… Remember—the opposite of absolute oppression is absolute pleasure. There has always been an extremely dark side to Johanna’s work but there was always something very pleasurable about it too–something beautiful bordering on dark—reminiscent of those scenes in Dante, Hieronomys [sic] Bosch or William Blake.18

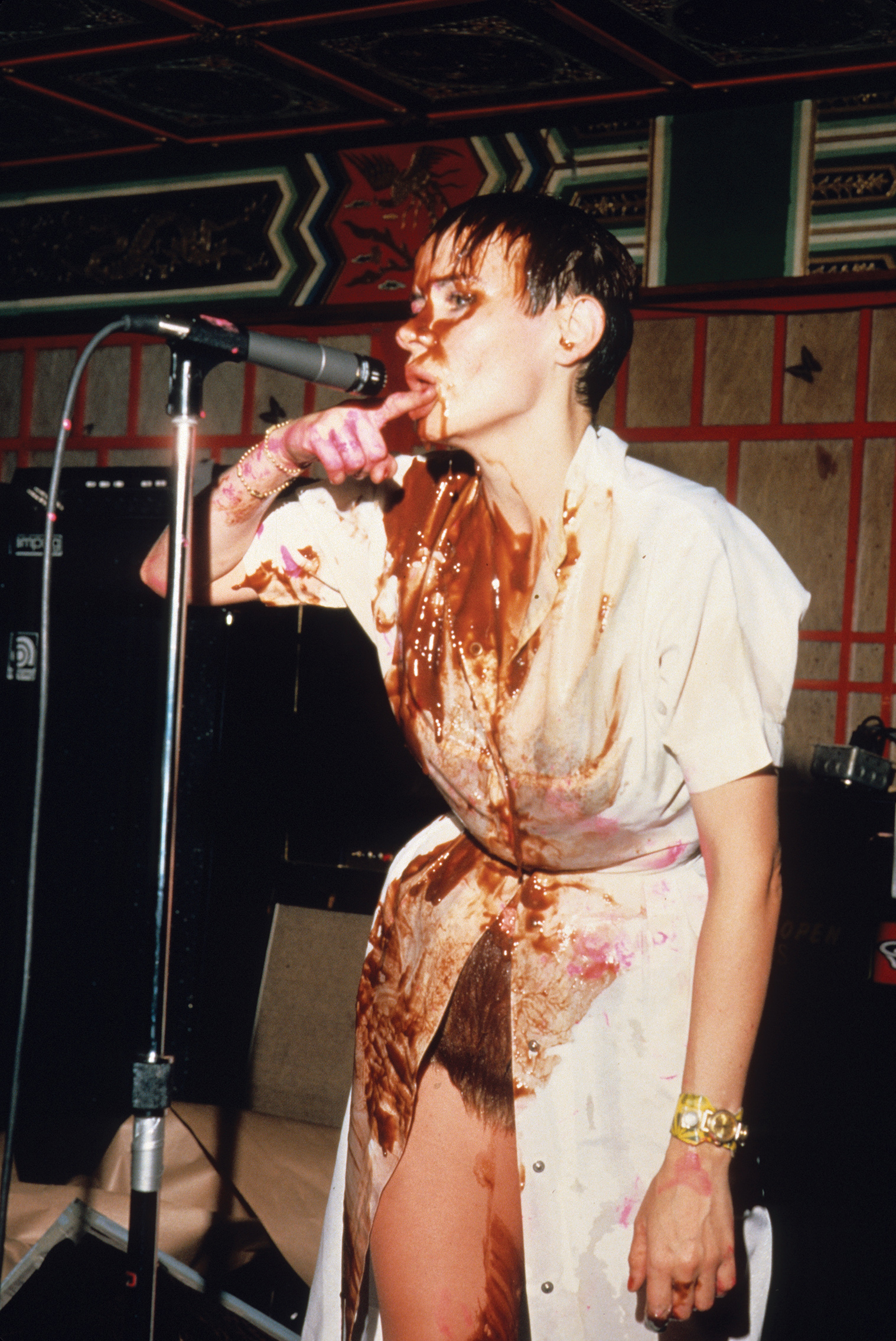

Photo shoot of Johanna Went for Chic magazine, early 1980s. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: David Arnoff.

Just as Went collaborates with noise-makers, she is guided by a deep sense of co-participation with her objects and costumes, which comprise a vast array of items cobbled together literally hours before each show. Most are made from detritus found on the streets: sex dolls trawled from the dumpster behind the shop where Mark Wheaton once worked; rolls of plastic, fabric, cardboard, and other discarded materials; pantyhose stuffed to resemble deformed bodies; scraps of lurid red vinyl crafted into huge vagina-like headwear; baby dolls and plush toys sewn onto crude aprons or ponchos that turn bodies into Barbarella nightmares; and last, but not least, the ubiquitous blood and guts gleaned from the morning’s meat market. Sometimes dolls were set in pots of gelatin that Went would suck, as if on a bone, or she would repeatedly stab a prop, such as a vague figure crafted from a cardboard box, with a knife, releasing jets of (fake) blood she would then bathe in. Her costume might be a crude bridalesque formed by yards of net thrown over the head and secured by a giant gag-style plastic fried egg. The overall effect is Bosch channeled through a garment district dumpster. Through interacting with these apparently inanimate things, Went channels something not found in ordinary experience and perhaps not amenable to coherent critical thought. She says, “It’s as if they speak to me, or through me.”19

By all of the above means, Went pushes a grotesque aesthetic to the extreme, eschews narrative and logical progression, values visual cacophony, and achieves a high degree of interactivity with the audience. And if the form is chaotic, the content too is unstable—a dreamscape of fluctuating monsters and phantoms that aspire to revelation. Above all, Went has no need to thrust significance upon her audience under the guise of Culture; she simply trusts in our capacity to make something for ourselves from what she has to offer, however theatrical, entertaining, absurd, gross, or downright dumb.

Went has since performed a number of more elaborate shows—Interview with Monkey Woman (1986), Twin, Travel, Terror (1987), Last Spring at Grey Gardens (2002), and Ablutions of a Nefarious Nature (2007). These works include other performers, such as Annie Iobst and Lucy Sexton, formerly of Dancenoise; Tom Murrin; Stephen Holman; and Lily Greenfield-Sanders. However, her masterworks are the club shows. Unrehearsed, unruly, and often untitled, everyone who saw them speaks of the ecstatic mind-melting experience they induced. But given Went’s goal of direct experience, how are we to evaluate her work and legacy? Amelia Jones raises this question in her contribution to Live Art in LA, beginning with a citation from Derrida:

We yearn for experience of the live “without mediation, and without delay. Without even the memory of a translation.” This yearning in fact is translated into some of the more idealistic…practices, which…often fail to obtain “the memory of translation” in their seeking for the utopian potency of the moment… This structure in and of itself becomes one of the ways in which such practices easily get forgotten. Not only are they provocative, messy, and often resolutely un-codifiable…they may also have been initially performed with little attention to the “mediations” necessary for historicizing… What [then] can we say their legacy has been?20

Oddly, not the least appropriate way to address this question is through the concept of “genius.”

Johanna Went, Knifeboxing, July 27, 1984. Performance at Club Lingerie, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist.

Conclusion: The Genius of Went Work

According to the philosopher Nick Land, “genius” enters serious philosophy with the work of Immanuel Kant. After having established a “transcendental” structure for the mind in his first two Critiques, Kant was forced to write a third volume because he confronted the inconvenient fact that “utter chaos had still not been outlawed.”21 This is because Nature offers no guarantee of conforming to the transcendental system. We must keep firmly in mind that in Kantian discourse the term “transcendental” does not mean something above and beyond ordinary experience but simply means the conditions necessary for there to be any experience at all; that is, any comprehensible experience.

In other words, while Kant believed that the sense of experiential coherency could only be explained by the mind’s having an innate internal coherence-giving structure, and that this “transcendental” edifice could be analyzed and described, he also finally recognized that nothing assures that the empirical laws of external Nature are similarly consistent. That is, he recognized that nothing guarantees that the objective world conforms to the structure of our mental apparatus—that which enables us to make sense of this world. Nature, instead, might be governed by such a multiplicity of laws that it may never cohere. Logically then, our sense of experiential consistency might be produced not by the facts of Nature but rather by an ungrounded subordination of Nature to the structure of our own minds. Or, to use Kantian terminology, by the subsuming of Nature to our own faculties of representation. The appalling conclusion of this eminently rational inference is that the objective world may simply be beyond comprehension. From thence springs both Kant’s ideas on art and genius, and the “brutal war” into which Western philosophy has been locked ever since.22

Land outlines two attitudes to the incomprehensible that are pitted against each other in this war unleashed by Kant’s third Critique. For rationalists, the experience of an incomprehensible phenomenon causes the mind to become aware of its own complex mental faculties—specifically, the split between Understanding (the transcendentally necessary and “given” mental apparatus outlined by Kant in his first Critique) and Reason (the free, collective, and creative aspect of mind that forms new concepts and thus extends both knowledge and the range of coherent experience). Historically, at least for Kant, the first example of a free concept of Reason is the scientific notion of “mass,” that quantum of stuff that acquires weight when subjected to a gravitational field. Without such innovative concepts, science cannot progress.23 For true rationalists, no experience is, in principle, beyond mastery and coherence by the development and application of new concepts.

Johanna Went, Dancenoise (Lucy Sexton and Annie Iobst) and Tom Murrin, Primate Prisoners, Jan 10, 1987. Performance at Abstraction Gallery, Los Angeles. Curated by Jack Marquette.

On the other hand, even the most rationalist of philosophers, including Kant, struggle with the fact that human experience often seems marked by the stain of some “otherness” that, whilst it undeniably subsists, remains beyond comprehension, forever defeating our attempts to contain it with concepts. Land calls this non-rationalizable surplus “nature with fangs.”24 And its mark is upon us all. For some time, philosophers thought of this “otherness” as a pure force of Nature, something that irrupted into human consciousness from without. Later however—at least for some—this idea faded, and the incomprehensible disrupter began to be seen as part of the psyche itself. This is where psychoanalysis parts ways with philosophy, and the psychoanalytic concept of subjectivity as inherently split (between consciousness and the unconscious) distinguishes itself from the purely philosophical concept of a subject that, no matter how complexly composed, is in some sense unified. The split subject of psychoanalysis—which haunts even the most dogged rationalists—is an I infested with an It, an It that is more present in the I than the other way around. For Freud, the formula for this subject is: where It was, there I shall come to be—a temporality of dizzying complexity. This It, which irrupts into the subject with the force of a trauma, defies comprehension, for It annihilates the sense of (coherent) selfhood.

From the rationalist perspective, there must be some concept adequate to grasping the It, even if we haven’t yet found it. It is just a matter of time and progress. To the non-rationalist (who may be highly rational), there is simply a limit to the human mind, some experiences that even Reason (as well as Understanding) cannot grasp. Hence the “war.” One either believes there are incomprehensible experiences, or one believes that these are simply the effects of an as-yet-undiscovered concept/knowledge. But one thing is certain, we cannot claim simultaneously that an experience is incomprehensible and also give it a concept or name. At least we cannot do so with consistency; we cannot do it philosophically. To put it another way, we can never build a properly philosophical metaphysics on the concept of the inconceivable, for this is a contradiction. However, many religious and spiritual systems are founded on just such a phenomenon. Although rationalist philosophy must avoid, even deny, the real existence of incomprehensibility—precisely because we cannot coherently speak about it—for Kant and many of his successors, this accursed phenomenon is the essence of both genius and art. As Land points out, for Kant, “Genius is nothing like a character trait, it does not belong to a psychological lexicon; far more appropriate is the language of seismic upheaval, inundation, disease, onslaught of raw energy from without. One ‘is’ a genius only in the sense that one ‘is’ syphilitic, in the sense that one is violently problematized by a ferocious exteriority.”25 Land also notes, “Kant’s word ‘genius’ is the immensely difficult and confused but emphatic…thought of an utterly impersonal creativity that is historically registered as [a] radical discontinuity…as ‘order’ without anyone giving the orders.”26

One way of understanding this strange idea is that the genius is one who is not traumatized by an inundation of otherness; geniuses welcome, invite, or even give themselves up to it. To use more Kantian terminology, geniuses can turn the “negative pleasure” of self-annihilation into the positive force of creativity that produces art. Thus, art too “irrupts into European philosophy with the force of trauma.”27 And, as Land states, “Kant is quite explicit that a generative theory of art requires a philosophy of genius, a readmission of accursed pathology into its very heart… Kant only manages to control this disruption by maintaining art as…implicitly marginal.”28 But if Kant contained the trauma of art through its marginalization, his successors could not. The demands of the geniuses and their art were simply too disturbing. From Schelling to Schopenhauer, art, the aesthetic, and the geniuses who produce them were sirens, luring otherwise rigorous philosophers into ever more dangerous waters.

Finally, in the nineteenth century, Nietzsche split art from philosophy entirely by distinguishing between two radically different kinds of aesthetic experience and two radically different orientations of the subject to its object-other, the artwork. These are the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Johanna Went performing at the Hong Kong Café, Los Angeles, 1979. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Scott Lindgren.

Distinguished by a contemplative or distanced relation to the artwork, the Apollonian subject preserves some of philosophy’s aims, including its desire to use the object-other as a means for its own self-aggrandizement. This distance, within which the subject claims to become more self-aware precisely by alienating itself from some other, is the essence of what, since Kant, has been called “critique,” and it lies at the heart of the modern/contemporary art project. In other words, Apollonian art aims, like Socrates, at increasing the contemplating subject’s self-awareness, rather than increasing its knowledge of (its) others.

On the other hand, the Dionysian subject intentionally loses its self by allowing an incomprehensible otherness to flow into its space. The aim here is not to “know” the other in the sense of being able to explain or put a label on it, but in order to actually experience It. Thus, as Nietzsche rightly points out, Dionysian art must break down the “distance” between audience and spectacle by being more than, or other than, “contemplative.” Indeed, a truly Dionysian artwork can never be a mere “spectacle.” It must by definition be immersive and participatory, inciting not critical contemplation but a self-forgetting in which Freud’s dictum is reversed, as the It comes to be where the I was. For Nietzsche, only this kind of heroic self-annihilation can save us from the fastidious, brittle, and puny self-consciousness that so characterizes modern subjectivity.29

Johanna Went is a Dionysian genius, a Siren whose irresistible song cannot help but lure us into the temptations of ecstatic, participatory, and brave self-annihilation.

Christine Wertheim’s books include three poetic suites, the book of ME, mUtter-bAbel, and +|’me’S-pace; three edited literary anthologies, Feminaissance, The n/Oulipean Analects, and Séance, the last two with Matias Viegener; and Crochet Coral Reef, with Margaret Wertheim, about their decade-long art-science-feminist-community project. She has received grants from the Annenberg and Orphiflamme Foundations, and teaches at the California Institute of the Arts.