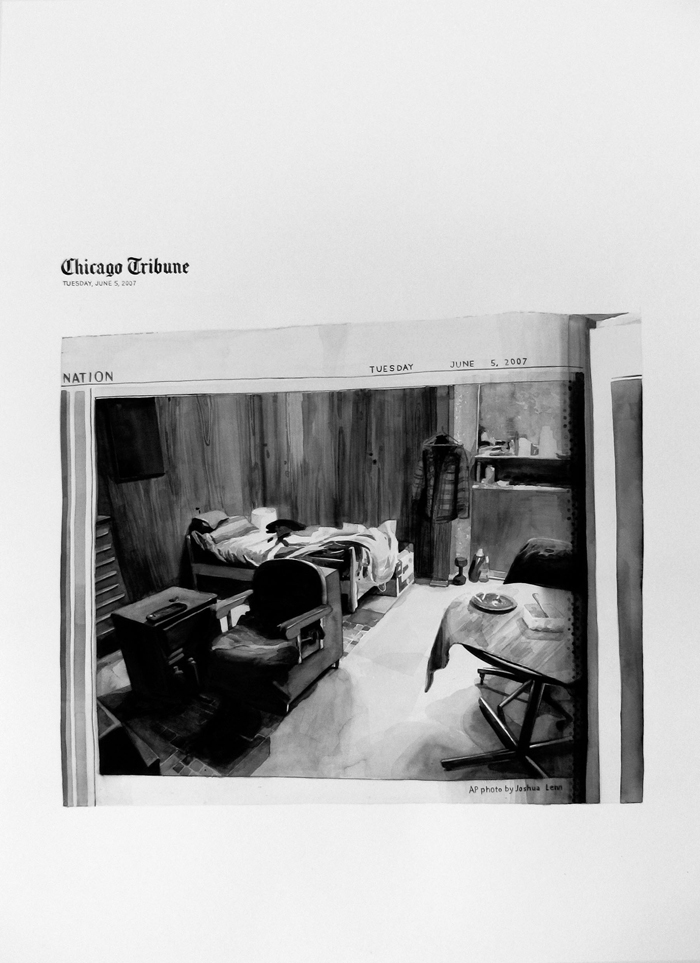

Jana Gunstheimer, Status L Phenomenon #1, 2007. Watercolor on paper, 95.5 x 70 cm. Courtesy of Galerie Römerapotheke, Zürich and Galerie Conrads, Düsseldorf.

The headlines for Chicago News, printed on Tuesday, June 5, 2007 read:

“Members of upper class affected by inexplicable phenomenon of lost status—CRISIS!”

“Lake Point Tower plus two luxury villas suddenly replaced by affordable homes—Occupants seem different”

“Bush proclaims state of Emergency for Chicago”

“Insurers decline Liability”

“Jesus is punishing us for our sins”

“Sox Pride Member Andy J: Gone Insane?”

In tiny type located just under the barcode and recycling logo on the front page of Chicago News is printed “An original artwork by Jana Gunstheimer.” Tabloid formatted, Chicago News is not available on newsstands throughout the greater Chicagoland. Instead it is available “free” in the contemporary project gallery that dead-ends the Late Twentieth Century Art wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. Here stacks of the newspaper are the centerpiece to the young German artist’s first museum exhibition in the United States. As the current installment in of the Art Institute’s Focus series—the museum’s singular sojourn into contemporary practices—Gunstheimer’s pointedly political project is duly specific to the city of Chicago and America’s annual summer celebration of freedom on July 4th.

Titled Status L Phenomenon (2007), Gunstheimer glibly disseminates Orwellian fiction throughout all aspects of her installation.

Comprised of two wall drawings, fifteen framed watercolors and the stacks of newspapers that she considers an artist’s book, Gunstheimer employs an equivocal visual language and suppositious narrative so as to critically expound on the political, social and cultural distortions that metastasize under economic hierarchies. The title of her exhibition references the absurd phenomenon of “lost status.” In the case of Status L Phenomenon, Gunstheimer builds a deceptive, albeit elaborate, storyline in which Chicago’s Lake Point Towers, a seven-room villa on LaSalle Street, and a luxury residency on Prairie Avenue are instantaneously transformed, according to the Chicago News, into “shockingly ugly” tenements.

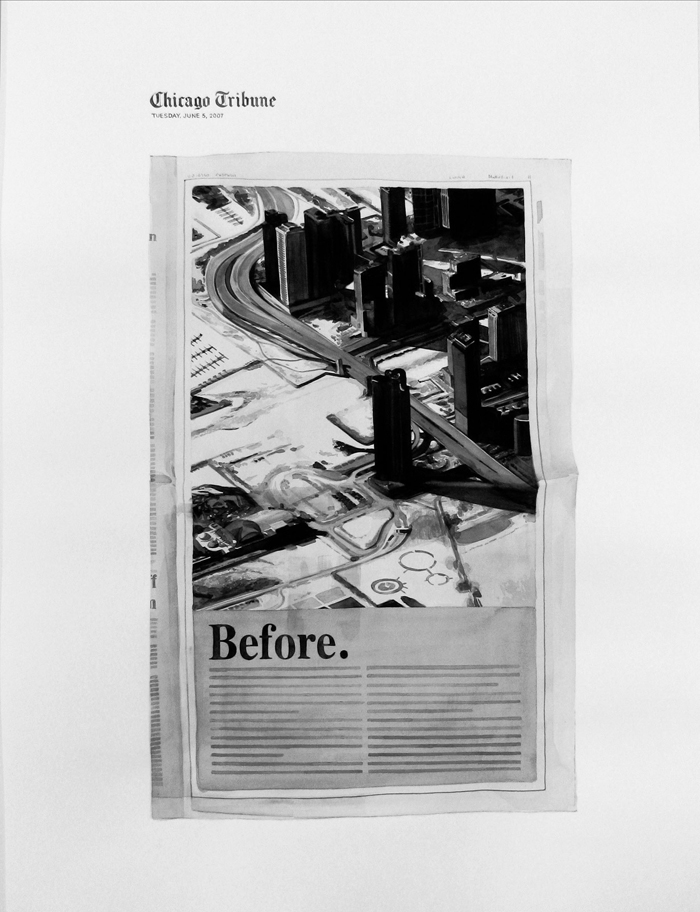

“Before” and “After” drawings of the effected buildings, officious graphics, diagrams and maps, accompanied by a precise timeline, constitute a bold, double-page spread in Gunstheimer’s newspaper. This same news graphic is reproduced, writ large on one gallery wall. The text block below the line drawings of the “Before” image of the corner-less, vertical Lake Point Towers and the “After” graphic depicting a dilapidated, dissolving vertical structure states:

1:49 p.m.

Lake Point Tower turns into a seedy tower block of social housing and disastrous facilities. 345 residents were at home at 1:40 p.m. and seemed unaware of the radical change. Their behavior suggests brainwashing. Former residents of luxury single apartments are herded into tiny, rundown roomes [sic] with their neighbors. Six to eight occupants share one bedroom and one kitchen.

In addition to fake advertisements such as the full-page ad that reads “Capitalism is Dead,” sponsored by an imaginary investment firm named Besserem Trust, the Chicago News is complete with journalistic-style reports covering the Chicago crisis. Fictional News Service and staff reporters cover all the angles of Gunstheimer’s pretend calamity. For example, Liz Taylor, staff reporter, interviews a former ex-millionaire and resident of the former luxury villa on Prairie Avenue named James Dobbes. When asked by Taylor “What are you going to do now?” Dobbes responds, “I very much hope that the matter will be cleared up and we can return to our previous lives.” Gunstheimer’s photo-based watercolors are reproduced in the newspaper as illustrative accompaniments to the reports. In a large black-and-white image, Dobbes is shown washing dishes in his now sub-standard kitchen because his “domestic staff are now sub-tenants,” according to the picture’s caption.

The watercolors, when employed as illustrative fodder in Gunstheimer’s tabloid, work perfectly. Thumbing through the newsprint pages, the images appear just “off,” appropriately echoing the misrepresentation and disingenuousness of her project.

Gunstheimer diligently records photographic sources, which she then recontextualizes into her printed fiction, offering the appearance of empirical evidence. For example, on page seven of Chicago News, the “Public Reaction” section soliciting feedback from people around the country is accompanied by small-size headshots that upon close inspection are reproductions of clumsy watercolor paintings of found photographs.

The fifteen trompe-l’oeil watercolors hanging in the gallery are there to further verify Chicago’s Status L Phenomenon. Doctored simulacra of the front pages of The New York Times, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and USA Today confirm Gunstheimer’s fiction with more fiction. Images accompanied by headings that reads “CRISIS,” “BEFORE,” or “HAPPY BIRTHDAY AMERIKA!” and newspaper mastheads painted in the upper left corner complete these watercolor composites. But these watercolors, when cleanly framed and adorning the gallery walls, lose their conspiratorial function. It is difficult to see them as little more than art product, the commodities to a project that paradoxically works to undermine the consuming habits and life styles of the privileged classes.

Unlike the newspaper reproductions, these works are not believable as hand-painted, faux facsimile. Nor do they carry the same authority that they have when used as photographic evidence in Chicago News. Unfortunately, these renderings work against the elaborate fiction and declarative reporting of the newspaper because they are painted sloppily. These watercolors are depleted of visual interest that even an appropriation painting is capable of imparting. Gunstheimer’s monochromes lack a deft, fluid hand, appearing stagnant and flat. Her wall graphics too, look hurried and strictly illustrational. Yet when the wall graphics and watercolors are reproduced in her newspaper, Gunstheimer’s awkward hand and wooden compositions find strength, imbuing empathy into Gunstheimer’s dystopic fantasy.

Gunstheimer’s brainchild NOVA PORTA is a semi-fictional organization with memberships, a quarterly newsletter, Maßnahme, and a website (www.nova-porta.org). Loosely defined, NOVA PORTA means “new door,” and its goal is to create an alternative society. In the catalogue essay to Gunstheimer’s exhibition, curator Lisa Dorin writes, “The organization serves as a vehicle for the artist to parody real-world hierarchical structures and arbitrary bureaucratic methodologies. Gunstheimer responds to the transformations she sees taking place in contemporary German civil society—namely post-industrial desolation, drastic unemployment, and rising levels of aggression among her generation.” In her project for The Art Institute, NOVA PORTA makes its appearance in an article on page five of Chicago News as a German risk management organization. According to an article titled “Trail Leads to Germany,” NOVA PORTA is conducting experiments on jobless people in a remote part of East Germany.

The post-cold-war transformation of the German State is at the heart of Gunstheimer’s fictions. It is a form of critique grounded in frustration. Central to her project is the notion that progress leads to less labor and less labor leads to purposeless, violent individuals.1 German sociologists have recently coined the word “Ostalgie,” a term that translates to mean nostalgia for the lost hopes of the former GDR (Ostalgie: (Ost [East] + Nostalgie). Growing numbers of Ostalgie magazines promote products that represent a bygone era in Germany where only one type of toothpaste or pickle was available for consumption: e.g. Perlodont toothpaste and Spreewald Gherkins. Ostalgie is more a condition of disillusionment with the promise of the democratic and capitalist state than a desire to return to a past form of oppression.

Parody and pastiche have been the critical tools of choice for many German artists. From Martin Kippenberger to Neo Rausch, Karl Valentin to Deiter Roth, disrupting the status quo via fiction or a good fart joke has always done the job. Only now the status quo seems to be framed by the broken promises of the free market. NOVA PORTA’s website begins with an inciting quote by Arnold Hofhaus: “The increasing brutality, tendency to violence and their escalation in our society harbor a social potential whose power has hitherto been little examined. We ought to learn to make use of it.” But these words, like Gunstheimer’s Status L Phenomenon and her organization NOVA PORTA, are merely tough-talk. As imaginative as her project is, it risks little. It is play-acting.

Jana Gunstheimer, Status L Phenomenon #2, 2007. Watercolor on paper, 95.5 x 70 cm. Courtesy of Galerie Römerapotheke, Zürich and Galerie Conrads, Düsseldorf.

“We are encouraged not only to suspend our disbeliefs, but to plunge headfirst into the narrative,” writes Dorin about Gunstheimer’s Chicago News. Yet we do this when we read The Onion, or a Philip Roth novel. Certainly, Gunstheiemer’s project is a welcome antidote to the all-prevalent idiosyncratic narrative. It also marks a welcome move in art practice to take on the politics of critique. However, these forms of critique are slippery. The critical practices such as those put forward by Jana Gunstheimer or The Bernadette Corporation wag a finger at contemporary ills while still offering up cloying art product.2 The risk of losing inclusion in the cultural and economic authority of the art apparatus is far too great. Thus, artists are becoming adroit at employing misrepresentations, duplicity and bluffs.

The Plot Against America, Philip Roth’s alternative history of twentieth century America where Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh wins the presidency from Franklin Delano Roosevelt, is a piece of contemporary fiction that gives haunting pause to the notion of truth. Of course, rewriting American history is no more plausible than Status L Phenomenon taking hold of Chicago. But because The Plot Against America avoids equivocality and pastiche it is less ridiculous while still harshly critical. Employing the poetics of realism is risky. Perhaps when all the cheeky slippage between fact and fiction has been played out, meaningful critique can take place without disclaimers that read: “THIS IS AN ORIGINAL WORK OF ART BY JANA GUNSTHEIMER. ALL NAMES ARE FICTITIOUS. ANY RESEMBLANCE BETWEEN NAMES IN THIS ARTWORK AND INDIVIDUALS LIVING OR DEAD IS PURELY COINCIDENTAL.”

Michelle Grabner is an artist and critic living in Oak Park, IL where she and her husband Brad Killam run The Suburban, an artist project space. She is a professor in the Painting and Drawing Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.