Visitors entered the Jack Goldstein x 10,000 exhibition through a set of double doors that opened into a small gallery that functioned as a kind of foyer. A transitional architectural space that is commonly found in theaters, foyers bring the public exterior of the building into conversation with its interior drama. It provided the perfect setting for viewing Goldstein’s 1978 silent film The Jump. Projected onto a white square painted on a red wall, the film presents a poised figure that appears seemingly out of nowhere, sutured into an otherwise non-dimensional black void. We are riveted by the figure’s presence, animated by a dazzle of lights that persistently call our attention like a strip-club marquee. Reaching up into the darkness, the figure performs a back flip that transitions into a somersault, and then, quite inexplicably, collapses in on itself, losing all form and dissolving into a dot of blinking lights before receding entirely into the surrounding void. Despite the slow-motion recording, the figure disappears before we can comprehend him. What are we to make of this strange presence? The screen remains dark just long enough for this unsettling question to register. The figure returns, this time momentarily caught in a posture reminiscent of a rag-doll before bouncing on an invisible ground that propels him forward into another flip; the movement carries him out of frame, and he is gone once again. He will return and orchestrate one more back flip into the void, this one faster, projected in “real” time. This series leads viewers to anticipate a fourth apparition, which never comes. Instead, a still image of the figure in profile flashes twice against the dark background, marking the film’s conclusion and connecting our physical experience of anticipation with the figure’s presence in memory before the film loops and the series of jumps begins again.

Jack Goldstein, The Jump, 1978. 16 mm film, color, silent, 26 seconds. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and the Estate of Jack Goldstein.

The Jump introduced Jack Goldstein x 10,000, the first American retrospective of Goldstein’s work. Curated by Philipp Kaiser, the retrospective was originally slated for exhibition at Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), but it was cancelled in 2010 with the arrival of MOCA’s new director, Jeffrey Deitch. Luckily for Southern California audiences, Kaiser was able to take the exhibition to Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA). The exhibition featured over fifty works executed in an exceptionally wide range of mediums, including film, installation, vinyl records, painting, text, graphic design, and documents from performance works. Coming on the coattails of the J. Paul Getty’s Pacific Standard Time project, the OCMA retrospective further elaborated the significant contribution that Goldstein, born in Canada but raised and educated in Southern California, has made to contemporary art. As Kaiser observed, Goldstein’s work embodies “a fundamental paradigm shift in American art during the late 1970s. Given Goldstein’s legacy and his increasing relevance to younger artists, this retrospective of his work is essential to the larger re-evaluation of post-1960s American Art.”1

Goldstein was part of the first generation to grow up with television, which introduced the world to the oxymoron “live recording,” a condition of representation that greatly intrigued Goldstein. Writing about his intentions for The Jump, Goldstein explained: “The wall [onto which the film is projected], no longer simply a neutral surface, becomes spatially integrated with the figure: a stage in which movement itself, as spectacle, becomes pure image: to jump becomes the jump.”2 By underscoring the grammatical transition from an infinitive verb to the definitive noun form, Goldstein directs our attention to the manner in which filmic representations translate abstract ideas of action into the singularity of an expression that is nevertheless fixed within the frame of a representation. Goldstein realized that by capturing movement, televisual forms effectively redefined the representation plane as an event space. In the televisual, the categories of “live” and “recorded,” once understood as being mutually exclusive, collapse.3 Goldstein’s film The Jump, like much of his work, was designed to probe this contradictory form and explore how it addressed viewers in an unprecedented manner, transforming their relationships with pictures.

By installing The Jump at the gateway to Goldstein’s retrospective, Kaiser underscored the significance of this work for the development of Goldstein’s larger oeuvre as well as his professional career. Before it was even finished, The Jump was cited in Douglas Crimp’s curatorial essay for the 1977 Pictures exhibition at Artists Space. Echoing Jean Baudrillard, the young curator claimed that Goldstein’s process of presenting an appropriated image that had been completely isolated from its original context pointed to the effects of media, revealing “that we only experience reality through the pictures we make of it.”4 Indeed, as Crimp—and later Kaiser— suggest, Goldstein’s work played a pivotal role in the advancement of the appropriation strategies that would come to define the Pictures Generation.

In 1979 Crimp published a revised version of his curatorial essay in October. In this much more widely circulated essay, Crimp offered an expanded discussion of Goldstein’s work, introducing The Jump through an analysis of Goldstein’s earlier performance works, which employed actual distance, colored spotlights, and dramatic soundtracks to give his audiences the impression of witnessing a live event as if it were a representation. Goldstein’s performance Body Contortionist (1976) is a case in point. A professionally trained contortionist, dressed in a spangled reflective costume, moved through a sequence of elaborate positions. The entire performance was enacted within a spot-lit circle of green light, with the audience positioned at a 25-foot remove. As Crimp explained: “the performances of Jack Goldstein do not, as had usually been the case, involve the artist’s performing the work, but rather the presentation of an event in such a manner and at such a distance that it is apprehended as representation— representation not, however, conceived as the re-presentation of that which is prior, but as the unavoidable condition of intelligibility of even that which is present.”5 Although visitors to the OCMA retrospective were unable to witness Body Contortionist or any of Goldstein’s other performances from the 1970s, the retrospective included framed documents that featured silkscreened images and descriptive comments about these performances.

Jack Goldstein, Suite of 9 Records with Sound Effects, 1976. A German Shepard, 45 rpm, red vinyl; The Lost Ocean Liner, 45 rpm, black vinyl; Two Wrestling Cats, 45 rpm, yellow vinyl; The Burning Forest, 45 rpm, red and white vinyl; The Tornado, 45 rpm, purple vinyl; A Swim Against the Tide, 45 rpm, blue vinyl; The Dying Wind, 45 rpm, translucent vinyl; A Faster Run, 45 rpm, orange vinyl; Three Felled Trees, 45 rpm, green vinyl. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and the Estate of Jack Goldstein.

Related to these performances but lesser known is Goldstein’s 1977 installation Burning Window, which was recreated for the OCMA exhibition. Unlike the immersive experience of most installations, Burning Window is composed of a completely sealed room. Visitors may gaze into the room through a standard-size window, but they are refused entry. The panes of the window are made of red, textured Plexiglas behind which invisible electric lights flicker, creating the illusion of a fire within. Like the physical distance of the performances, the sealed room articulates a perceptual distance completely separated from the frame of representation. Peering into this frame, viewers confront a tableau that performs without the assistance of actors. In this enhanced condition, representation acquires the spectacular veracity of a theatrical drama. Rather than describing or depicting, Burning Window performs its representational content. The installation presents the qualities of a fire separated from any visible figuration of a fire. In this regard Goldstein draws our attention to the spectacular effects of the signifier, the semiotic piece that shapes the delivery of an image’s content in a qualitative manner.

Jack Goldstein, Burning Window, 1977. The performance takes place in a long, empty, rectangular room with a black ceiling. One wall is painted red. A standard panel window with a red frame is installed on the red wall. Behind this are textured red plexiglass panes; flickering electric candles simulate the appearance

of fire. The window functions as a “safe” but fragile barrier in front of which the spectator is witness to the world outside as a measureless inferno. This spectacle, which may be felt ambiguously both as “real” and as a “cinematic” illusion, calls into question the “truth” of visual experience. Courtesy 1301PE,

Los Angeles and the Estate of Jack Goldstein. Installation at Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Photo: Chris Bliss Photography.

The physical installation of Jack Goldstein x 10,000 loosely follows the chronological development of Goldstein’s work with a few notable exceptions. The placement of The Jump (1978) is one. When viewers move out of the darkened gallery space where The Jump loops silently, they pass through another doorway and immediately confront Aphorisms (1982), a wall text composed in black and red vinyl letters. Although silent, Aphorisms ironically describes sound, and revels in the alliteration of repetition:

Sound is the space that frames an image as image from its object. Sound is the time of image that locates the spectator outside. Sound is the silence of image that limits the image as finite. Sound is the distance of image that defines dark from light. Sound is the memory of image that dislocates the origin from its object. Sound is the location of image that fixes the image in time.6

Adding to the irony of this piece was Kaiser’s placement of it in the exhibition. Reading the text, viewers were surrounded by the noise of projectors and the sound tracks of Goldstein’s films from the early 1970s that were being screened in the gallery space on the other side of the wall. In other words, Kaiser’s installation gave viewers an opportunity to experience the sound of Goldstein’s films at a distance and isolated from their visuals.

By juxtaposing Aphorisms with The Jump at the beginning of the exhibition, Kaiser not only set up a key for unpacking the formal and aesthetic concerns of Goldstein’s practice, but also he invited a reconsideration of Goldstein’s historical contribution to the Pictures Generation. In Crimp’s second “Pictures” essay, he pointed to the compositional effects of collage to argue that appropriation demonstrates how meta-narratives are pictorially constructed through the effects of framing. Thus, Crimp wrote, “pictures have no autonomous power of signification (pictures do not signify what they picture); they are provided with signification by the manner in which they are presented.”7 Although many of the Pictures Generation’s artworks entailed some form of collage (Troy Brauntuch, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Cindy Sherman among them), Goldstein’s did not.

While his productions almost exclusively featured appropriated imagery, Goldstein rarely combined these images with others to create a new or secondary context. Instead, as The Jump demonstrates, he presented his appropriated images in pictorial terrains that were specifically designed to drain off their signification and thereby focus viewers’ attention on the movement, color, or sound of the imagery, which is to say the qualitative content of an image that the signifier conveys. In fact, the spectacular figure that appears in The Jump was appropriated from Leni Riefenstahl’s 1938 Nazi propaganda film Olympia. Goldstein specifically engaged the animation process of rotoscoping in order to isolate the movement of the depicted divers. Yet, he kept the source of this image secret because he knew that the cultural and historical symbolism of Riefenstahl’s narrative would dominate viewers’ reception of the film, blinding them to the more subtle, qualitative affects of the diver’s movement. As Goldstein explained, “Animation eliminates all anecdotal and subjective content while retaining the reality of the action.”8 If, as Crimp described, the Pictures artists were framing images within the symbolic content of other images, Goldstein was stripping away and even suppressing the symbolic and situational context of his appropriated imagery, instead enhancing sound, color, and movement to bring emphasis to its temporal content. Goldstein denatured imagery in order to unleash its affective power. Thus, where most of the Pictures Generation’s artworks demonstrated how imagistic frames produced “ideological” content, Kaiser’s installation drew attention to the manner in which Goldstein’s work underscored the more expressive qualities of images, which also shape and transform the meanings that pictures convey.

Goldstein’s practice encompassed a wide range of mediums, and often featured the same image or form mediated through several different material expressions. For example, a barking German shepherd appears in the film Shane (1975) and is heard in a sound work, recorded onto a red vinyl disk (A German Shepherd, 1976), which then operates as a performative sculpture. Two Fencers are aurally represented on a white vinyl recording and visually depicted in a staged performance, both created in 1977. Likewise many of his Untitled (1969–71) sculptures represent teetering towers composed of stacked identical components, a motif that is repeated in his 1972 film Some Plates. In an interview Goldstein described his movement of imagery through different mediums and materials as a displacement of sensual perception, “something could come in through my ear and come out through my eyes.”9 Similarly, Goldstein viewed his decision in 1979 to shift his practice and focus on painting as both a practical career move and simply a decision to focus on the movement of still images from history into other expressive terrains.10

As Kaiser’s curatorial essay suggests, the critical assessment of the Pictures Generation is complicated by an almost “blinding” influence of theory on both its production of work and its historicization. This was particularly apparent when it came to painting. In fact, Crimp’s second “Pictures” essay polemically situated the development of the Pictures Generation and their specific use of appropriated imagery against a concurrent resurgence in expressionistic painting. Crimp’s critical positioning of the work was part of a much larger critical debate that dominated discourses in the late seventies and early eighties. This was clearly evident in the reception of Goldstein’s shift to painting. However, when seen through the distance of history and within the larger context of Goldstein’s retrospective, the paintings become more of an extension of Goldstein’s efforts to isolate the expressive qualities of imagery in a representational form.

Jack Goldstein, Untitled, 1981. Acrylic on canvas, 84 × 132 in. Collection Melva Bucksbaum and Raymond J. Learsy. Photo: Brian Wilcox. Courtesy Melva Bucksbaum and Raymond J. Learsy and the Estate of Jack Goldstein.

If Goldstein’s source for The Jump in Riefenstahl’s film went unnoticed for many years, the same cannot be said of his appropriation of Margaret Bourke- White’s 1941 photograph, Air Raid over the Kremlin, Moscow. Goldstein’s Untitled (1981) reproduced Bourke-White’s image on a grand scale (84 × 132 inches). Excised from its historical register, the image can no longer convey the moment before catastrophe, before the German bombers release their destructive cargo. Instead the dark silhouettes of the building’s spires placidly stand erect, completely still and impervious to the effects of time. Throughout his practice, Goldstein maintained both a brute fascination and fundamental suspicion of the power that images orchestrate. Accordingly it is not surprising that he was particularly interested in the spectacle of war, but Goldstein only ever encountered this particular spectacle through mediated representations. His paintings engage appropriated images with the intention of expanding the power of this mediation. Quite effectively, Goldstein’s painting flattens out the rich tonal range of Bourke-White’s photograph and empties the image’s sublime content, transforming it into something more akin to a graphic meme that indirectly collides with Hollywood’s more romantic renderings of World War II, which provided the source for the images that appear in other paintings from this series.

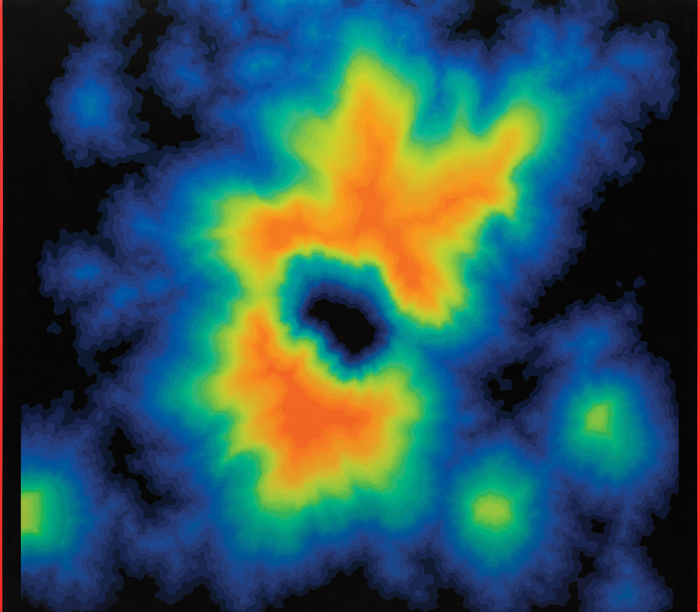

Jack Goldstein, Untitled, 1988. Acrylic on canvas, 84 × 96 in. Vanmoerkerke Collection, Oostende. Photo courtesy Vanmoerkerke Collection, Oostende, and the Estate of Jack Goldstein.

The second half of the 1980s were a productive time for Goldstein, when he created a number of strange yet visually compelling paintings that depict biomorphic shapes. Despite their abstraction, Goldstein said that many of the painted images were derived from computer-enhanced digital pictures of the topography of skin.11 Untitled (1988) is a case in point. It suggests an aerial thermal image in which the registers of heat are marked out in concentric layers of color. In fact when seen from a distance, the central fiery ring-like shape appears to radiate light. The horizontal edges of the canvas are delineated by narrow strips of green, which actually cause a visual vibration, enhancing the overall sense of movement that the painting generates. Nevertheless, closer inspection of the picture plane reveals a surface that is almost sculptural, for numerous layers of color appear to be stacked atop each other with their edges rigidly delineated by tape that has since been removed. By mixing formal references to the physicality of sculpture with the more ethereal fluidity of radiating light, Goldstein’s painting challenges us to consider how light and by extension images permeate the presumably sealed boundaries of our bodies. In fact, when seen from this perspective, Goldstein suggests that the body’s skin functions as another type of transitional gateway that brings the dramas of the exterior world into conversation with our more private interiors.

Marie B. Shurkus is a contemporary art historian and media theorist. She is Visiting Assistant Professor of Media Studies at Pomona College and a core faculty member of Vermont College of the Fine Arts MFA in Visual Arts Program.