Dall’ arte di far manifesti: The Art of Making Manifestos1

Reviewing an Italian Futurism exhibition is akin to reviewing the Vatican: given its reach and the breadth of possible critique, it is difficult to survey from the ground. However, the ground may be the proper place to start, as Futurism was the first avant-garde meant for the masses. First, there was its debut by way of manifesto, “Le Futurisme,” published on February 20, 1909. The manifesto was a political tract: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti made it poetry. Like any fair lyric poet,2 he opens with a personal gesture that leads to an epiphany that illuminates universality. Like every good politician, the universal contains an agenda, a proselytizing program of bullet-points. In a contemporaneous letter, Marinetti wrote that a manifesto must be “de la violence et de la précision,” containing “l’accusation précise, l’insulte bien définie.”3 To take a tool of political theory and turn it into a literary work was to assert the danger that poetry had posed since Plato. To use art to insult and indict society was to make art that mattered beyond mimesis. To do both was to make the first move toward the first self-determined art Movement.4

Second, there was the mode of its debut. Not, as the Russians would soon do, via publication of their collectively composed A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, issued in 1917 in a small limited run edition, each palm-sized chapbook a handmade piece of art in its own right, the few and unique stamped and painted volumes passed, also hand-to-hand, among the converted and the predisposed. Or, as the Dadaists did later, as oracular performances later printed in a numbered and deluxe Recueil littéraire et artistique (literary and art review). Rather, the Futurists published their manifesto in a newspaper, and Le Figaro at that, the Parisian daily with the then-largest circulation in Europe. And on the front page.5 This is PR, not propaganda.6 Because third, and more to the point, at that point there was neither a Futurist art nor a Futurist art movement. Art historically exists in the imaginary as image (to be embraced or eschewed as the case may be) and as Image, the latter being the path out and into the former. First Kunst, then Gruppe. At the time of Marinetti’s first manifesto, Italian Futurism had no a priori image. There were no paintings, no sculptures, no aesthetic objects from which one might derive a sense of the declamatory subject. Italian Futurism started with the Imaginary as already imagined, sprung fully formed from the forehead and dancing from the fingertips of Marinetti himself. And his (and its) first piece was an advertisement for an illusory product. Or, looked at another way, as a work of institutional critique. Articulation, boys, then annunciation.

Ivo Pannaggi, Treno in corsa (Speeding Train), 1922. Oil on canvas, 39 1/3 × 47 1⁄4 inches. Fondazione Carima– Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata, Italy. Photo: Courtesy Fondazione Cassa di risparmio della Provincia di Macer-ata.

The Guggenheim exhibition Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe is, like Italian Futurism itself, a marvelous demonstration of an aesthetical-political movement that is as much manifesto as manifest. Physically, the museum is the perfect staging for the show: the form of the spiral was an enduring Futurist motif. It appears in everything, beginning with Marinetti’s parole in libertà work.7 The spiral appears in Marinetti’s Bombardamento aereo (n. 67) (Air Raid [n. 67]) (1915–16), continuing into aeropittura, the later flight-inspired art, such as Filippo Masoero’s Scendendo su San Pietro (Descending over Saint Peter), ca. 1927–37 (possibly 1930–33). The museum’s spiral form in this context references what Futurist painter Umberto Boccioni called “absolute motion,” defined as “dynamic motion that is inherent in an object,” which must be observed in its plastic constructions. In this exhibition, the Guggenheim’s architecture reveals itself both as static “absolute motion” design and as design to move crowds as crowds, which is also an act of rhetoric.8 And rhetoric is everywhere present, commencing with the show’s grand narrative. Chronologically and ideologically progressing from bottom to top, the exhibition begins with Marinetti’s newsprint manifesto and ends with the large post office murals of Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti): art and politics happily, officially, absolutely integrated. It’s a story about the triumph of art, and thus, the story of the triumph of the museum.

In a pre-show article in The New York Times, lead curator Vivien Greene described the Benedetta murals (in their first U.S. sighting) as the exhibition’s “grand finale,” saying, “It’s such a beautiful way to end the show. It ends it on a really positive note. Instead of lingering more on the end of the war, when poor Italy is so beat up it’s so depressing.”9 Leaving aside the propriety of lamenting the defeat of a fascist regime, especially one so prominent in the golden age of fascist regimes, the curatorial intent to present the totality of Futurism as its rehabilitation succeeds and fails in the same way its subject succeeded and failed. First specifically, then generally.

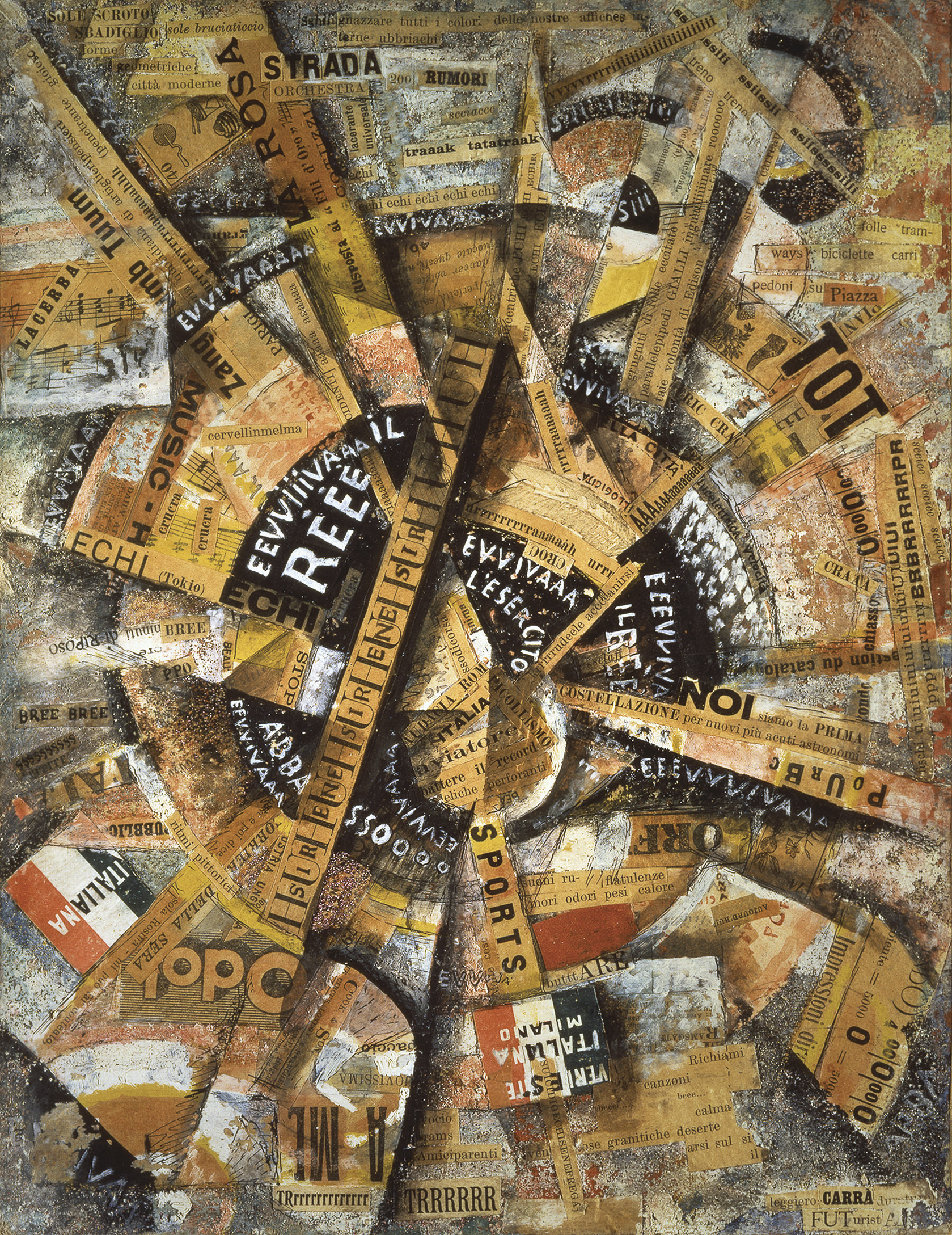

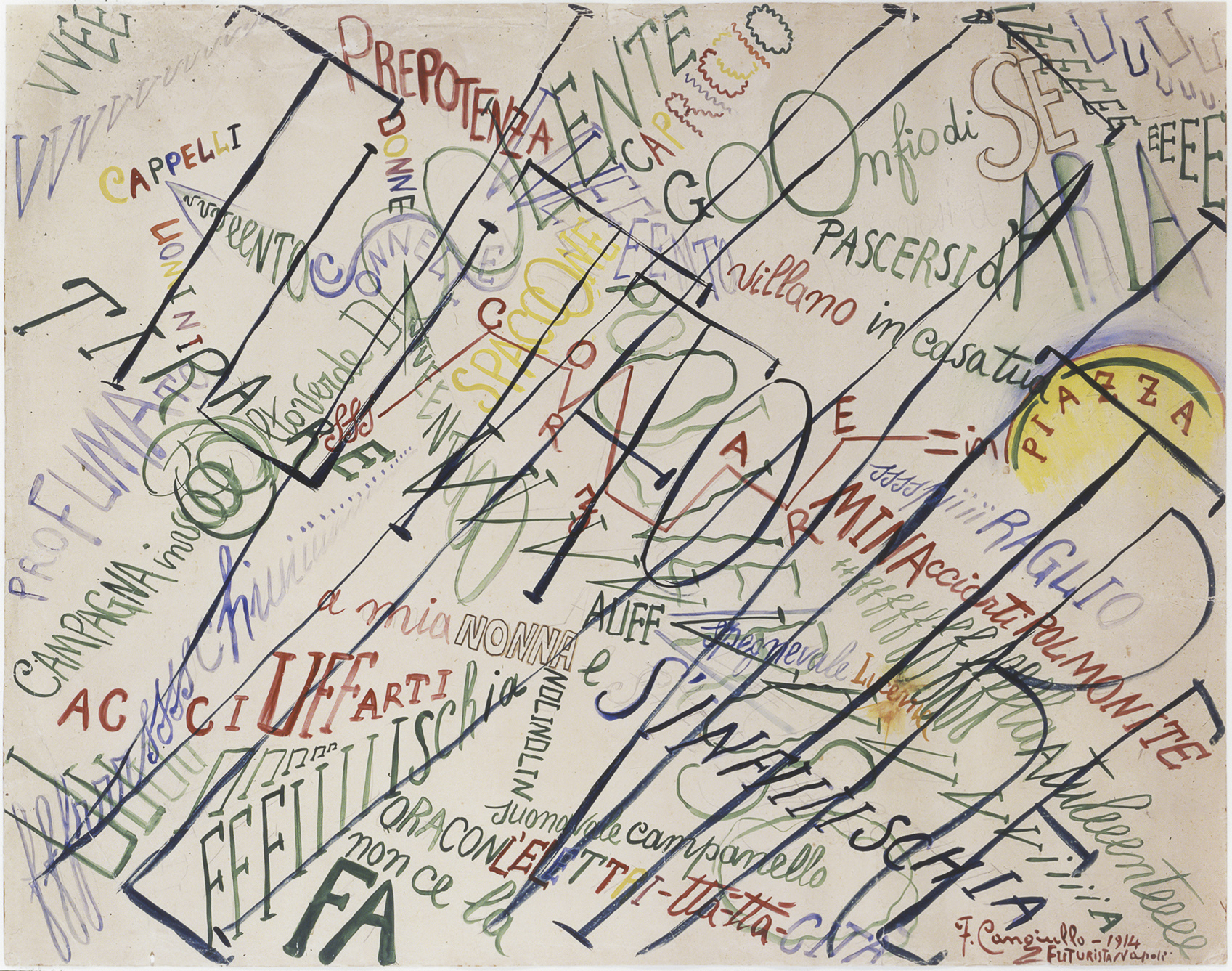

I attended the exhibition as a tourist, which is to say, as one of the crowd. There was a long line to get in the museum, and once inside, those in the atrium were energized. Given the Futurist ideal of d’arte totale, the total work of art that sets the spectator in the center of the aesthetic universe, our context in Frank Lloyd Wright’s vortex was complete. As noted, the exhibition moves chronologically; the initial works are familiar, the manifestos followed by the first paintings and the parole in libertà pieces. The paintings, like the poetry, wanted to capture movement, and did. Giacomo Balla’s velocity painting, Linee andamentali + successioni dinamiche (Paths of Movement + Dynamic Sequences) (1913); Carlo Carrà’s spiraling collage, Interventionist Demonstration (1914); Francesco Canguillo’s parole in libertà piece, Grande folla in Piazza del Popolo (Large Crowd in the Piazza del Popolo) (1914)—all attest to dynamism as the mode of the modern.10 Thus Umberto Boccioni’s great work, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), is not a break with sculpture and its history, but rather the art’s progression as literal movement. To move from Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BCE) to Rodin’s L’homme qui marche (1887–88) to Boccioni’s bronze is to study the mechanics of acceleration.

Carlo Carrà, Manifestazione Interventista (Interventionist Demonstration), 1914. Tempera, pen, mica powder, and paper glued on cardboard; 15 1/8 × 11 3⁄4 inches. Gianni Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Marinetti’s first manifesto is preserved, alongside his “Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista” and other key tracts, in a deep glass vitrine, as befits a Constitution and Declaration of Independence. The audience is thick before each of these iconic works, rightly not distinguishing between mediums. Newspaper and canvas, booklet and bronze: these are genres, and contain their genre-arguments, but should also be understood as platforms in the contemporary sense. In other words, they should be understood as the rhetorical difference between using YouTube and video—or at least knowing that there is an ideological message in understanding that these are separate contemporary mediums.

The buzz, and the crowd, dies down as the exhibition turns toward the 1920s and 1930s, as the movement became a march. An avant-garde cannot last for thirty years, and neither did Futurism, as avant-garde. The gesture of futurity, the “avant,” dies with its cultural domestication—both of the artists and the works. Marinetti became a member of the Royal Academy of Italy in 1929,11 and, as noted, Benedetta’s murals graced Mussolini’s postal walls. But again, Italian Futurism was never interested in revolution. The conversation it was having, and intended to have, was with (and for) Italy, not international aesthetics—let the Cubists fractal faces, the Dadaists go the way of aesthetic nihilism, and the Russians efface the bourgeois difference between art and life, along with the bourgeoisie themselves. The Italian Futurists wanted to fashion an Italian aesthetic for Italians, and let the world watch. To make “the total work of art,” meant to make, as Bruno Munari made, a Futurist Antipasti Service (1929–30), which was indeed an antipasti service, or a Futurist dining room set, such as Gerardo Dottori’s Sala da pranzo di casa Cimino (Cimino Home Dining Room Set), from the early 1930s. Or to make, as Giovanni Acquaviva did in 1939, a set of commemorative dishware, called Life of Marinetti, which included the Facismo Futurismo (Fascism Futurism) plate. The total work of art included both architecture and advertising. There are Futurist designs for terminals and cathedrals—Tullio Crali, Airport Terminal, Urban Airport (1931) and Alberto Sartoris, Notre-Dame du Phare, Plan for Fribourg (1931)—and a series of Futurist advertisements for Campari, the Italian cordial, made between 1928 and 1931 by Fortunato Depero.

Francesco Cangiullo, Grande folla in Piazza del Popolo (Large Crowd in the Piazza del Popolo), 1914. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper; 22 3⁄4 × 29 !/8 inches. Private collection. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

While the 1939 cover of the Italian Futurist art journal Artecrazia announced “the Italianness of all modern art,” Futurism was often more immediately concerned with promoting modern-artness for all Italians, manifest in high- and low-end product placement. This dedication to branding explains some of the complexities of Marinetti’s three-decade long relationship with Mussolini. The Fascists were ambivalent toward Futurism. They wanted to draw upon the glories of the prior Roman Empire and praise the goodness of the Italian peasant while also glorying in the sleek possibilities of futurity and the considerable cultural cachet of Marinetti himself. The Futurists were less ambivalent: they wanted the cash and the cachet. So in 1919, Mussolini founded his Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, and Fascists and Futurists together sacked the offices of the Socialist Party paper Avanti. By way of bookending, in an unsuccessful effort to save Artecrazia from suppression, Marinetti claimed in 1939, according to the Guggenheim timeline, that Futurism was “the embodiment of Italian nationalism and, having been born in Italy, cannot be accused of being a foreign element in Italy; additionally, he claims there are no Jews in Futurism and that Jews have never been instrumental in the creation of modern art.”12

This connection between Futurism and Fascism is the exhibition’s bugbear. While it is true that Marinetti and Mussolini were not lockstep in their aesthetic visions, neither were they antithetical. In his otherwise excellent Artforum review of the show, Ara H. Merjian sees the “graceful museumification” of Futurism as a final irony in the movement’s ironic trajectory: from Marinetti’s initial “scorched-earth rhetoric” and dismissal of state-approved art to the maestro’s later missionary position.13 But there is nothing ironic about a manifesto that fulfills its mandate. One of the jobs of a good advert is to point out the failings of prior products, then step rightfully into their place. Advocating in 1909 that Academy bronzes be tossed and that the race car be embraced (Marinetti was too parole-smart to let himself crack up in anything other than a Fiat) was not “scorn for the public,” but simply knowing how the public prefers its hunks of shiny metal. Beginning in 1919, Marinetti used the language of politics to sell a more contemporary, more “now” art; reversing the equation, Leni Riefenstahl used the language of art to sell a more contemporary, more “now” politics. That one is currently considered more artistic and less problematic than the other has less to do with irony and more to do with institutional success. In the propaganda game, Marinetti won, hands down.

Umberto Boccioni, Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio (Unique Forms of Continuity in Space), 1913 (cast 1949). Bronze, 48 × 151⁄2 × 36 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989. Image Source: Art Resource, New York © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gerardo Dottori, Sala da pranzo di casa Cimino (Cimino Home Dining Room Set), early 1930s. Table, chairs, buffet, sconces, and sideboard; wood, glass, crystal, copper with chrome plating, leather, dimensions variable. Private collection. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Daniele Paparelli. Courtesy Archivi Gerardo Dottori, Perugia, Italy.

Among the exhibition’s monumentally revisionist moments—and there are many—are the conceits that fascism is only ever Italian historical Fascism and all wars are the same. War, as Marinetti famously proclaimed, is “the world’s only hygiene.”14 So the Great War is presented as fodder for a multitude of Futurist pro-war projects, including Marinetti’s “Futurist interventionist theatrical road shows,” whose manifesto stated, “today it is only through the theatre that we can instill a warlike spirit in Italians.”15 Of course, Italy was on the side of the Allies in that World War, ergo fiat. Arguably, that it was on the other side in the Second World War might be at least a topic of internal institutional critique by the museum, if not condemnation. But no: the Second World War is presented by the Guggenheim as a platform for aeropittura and grand architectural designs, including a turn toward sacred art. Curator Greene in the catalog puts it mildly, “No artistic vanguard exists in a void—all are touched by their historical context. Thus, politics are also present here.”16 And while this is true, and another demonstration of the Wittgensteinian observation that all aesthetics has its ethics, and all ethics, its aesthetics, not all artistic vanguards embrace fascist politics.

For its part, the catalog is chock-full of similar rehabilitative asides, such as Claudia Salaris’s note: “The internal structure of Futurism was much like that of a political party, with a charismatic leader, a central directorate, and cells in the field…”17 This is patently not a description, as the author intended, of “a” political party, but of the political party, i.e., the party under a totalitarian regime. Or Salaris’s other howler: “It seems it was only the Italian Futurists’ embrace of Mussolini that gave them a bad reputation.”18 And Reifenstahl’s chumminess with Hitler was what made her such a drag at parties, too. But I am being unfair. What makes Reifenstahl one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century is that she brought politics into art in an absolutely constitutive fashion. Rather than save Marinetti from Mussolini,19 the curators here would have been well served to note how their off-and-on courtship was part of the demise of the art itself.

Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Sintesi delle comunicazioni aeree (Synthesis of Aerial Communications), 1933–34. Tempera and encaustic on canvas, 127 3⁄4 × 78 1/3 inches. Palazzo delle Poste di Palermo, Sicily, Poste Italiane. © Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, used by permission of Vittoria Marinetti and Luce Marinetti’s heirs. Photo: AGR/Riccardi/Paoloni.

The Guggenheim wants Futurism to be seedbed for all that follows, and in a sense it was, providing the start of what we perceive as performance art, sound poetry, visual poetry, graphic design, and the “art of noise” that led to Cage and beyond. At its best (and I would vote for the parole in libertà), Futurism did what it promised: it dynamically synthesized the cacophony and constancy of ultra-modern life. At its worst (the later pieces that look like old Palm Beach hotel art), Futurism ossified into a programmatic consumer-fantasy, a kind of haught culture. They say each generation has its translation of Dante, and so too each generation has its Futurism: the Dadaists seized the interventionist performance; the Fluxists extended Marinetti’s tattilismo (tactilism) work; Pop Art grokked the Campari adverts; and we get multi-platforming, #Futurism. Again, it might be worth noting that Futurism’s more cohesive offshoots, Dadaism and Surrealism, turned away from its positivist projection toward an interior landscape of refusal, particularly the refusal of language. Which might be the difference between war experienced as trauma, and war experienced as Traum.20

Manifesto, as critic Mary Ann Caws has written, contains its own parameters: “beginning with the manus, or Latin for hand—so, handcrafted—and then a fest (from festus) for its tight-fisted grip on whatever occasion it might be.”21 Where and when Futurism stalls, historically and in the museum, is where and when the manifesto as such is abandoned. When the move goes from the parole works, with the hand sweeping across the paper to indicate the arc of a crowd’s sounds, and the poet carefully prints K-K-K-K to inscribe the hand of the artist being also the finger on the shining trigger of a machine gun. Or the paintings in which the artist continues to turn circles, spinning the wheels of cars and lights and energy and sound as so many plates constantly kept going, propelled by the artist’s brush. And the crowd at the museum is left with just propeller-pictures, chunky blocks of Art Deco design, and aqua-colored murals celebrating systems of communication. When the hand is gone, all that’s left is the tight-fisted grip. When the march, in other words, becomes just a move.

Vanessa Place is a lawyer and founder of Les Figues Press. She is also CEO of VanessaPlace Inc., the world’s first poetry corporation.