1. Life Implicates Art

For the past forty or fifty years, Llyn Foulkes has been painting imagined landscapes and portraits of wounded white men, adding up to a whole besieged-male symbology. They are peculiar paintings, idiosyncratic laments for lost forms of American power, upholstered in a threadbare damask of half-feigned shame.

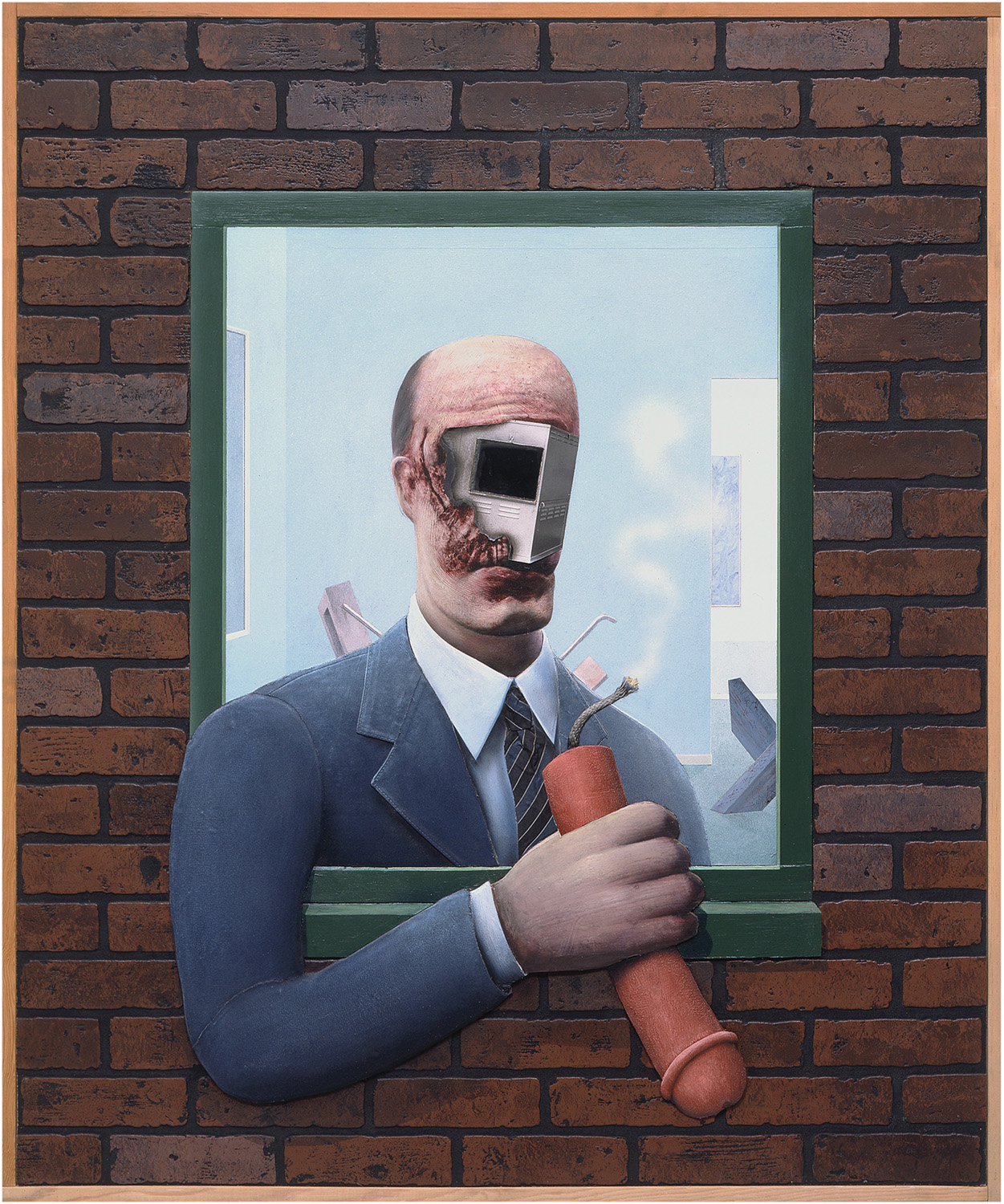

My experience of Foulkes’s retrospective at the Hammer Museum earlier this year was like a live analogue to his work, full of pet peeves and personal griefs. While I toured the galleries, ruminating to myself on the powers and limits of sardonicism, I was followed by a student docent playing her role to the hilt with a gaggle of well-kempt elderly ladies. She regaled them with paint-by-numbers connections between the artist’s imagery and his biography, titillating them with her attention to dynamite dildos and divorce therapy. They cooed and clucked in appreciation. The artist was on display as antique bohemian specimen, an exotic and neutered savage, not deconstructed but disarmed. Not once did I hear anyone puncture the playact by questioning something actually sordid—say, the subtle strain of sexism in the pictures. Even the offensiveness was sanitary, visitor and artist alike kept safe.

Naturally, I was as polite as could be to this caravan of self-satisfaction—I played my role, too. The sense that I was one of the slump-shouldered superheroes or hollow-eyed straw men of Foulkes’s paintings, my natural Western spunk eaten directly out of my brain by a Mickey-Mouse idea of citizenship, was difficult to suppress, even as my mind offered up all manner of sophistications to defend me, or the good natured blue-hairs and their hammy cicerone.

This is the effect Foulkes’s work can have—it’s easy to dismiss, but hard to scoff at. Or maybe easy to scoff at, but hard to dismiss. When the museum guard told me I couldn’t take notes with my pen—for “security reasons”— and supplied me with a tiny pencil, such as are used at bowling alleys and golf courses, my transformation felt complete. I was a Foulkes-esque Lone Ranger out in the ruined wilderness, with only my wounded pride as protection, nursing the memory of a time when the frontier was untamed and art was free. But I was also one of Foulkes’s taxidermied schlubs, stupefied by spurious nostalgia, trivial indignity, and uncharitable sanctimony, waving my stubby pencil menacingly in the air.

Llyn Foulkes, Art Official, 1985. Mixed media, 55 × 46 inches. Collection of Teri Kennady.

2. Of Mice and Men

This epic diminishment seems like the result of living with a cultural complaint that cannot be resisted (because it expresses real disappointment in an America hijacked by hypercapitalism) but also cannot be indulged (because it is based on absurd premises—individual heroism can save us, art lasts, there were good old days, etc.). Foulkes’s retrospective traced a remarkably fast slide into this state of impossible disillusionment. His early painting, from the early sixties, was firmly grounded in abstract expressionism, complete with Jasper Johns-esque framing and stenciled alphabets. It was dark and guarded, but earnest. His experience in the army in Europe had had an obviously powerful effect on his work—consider the disturbing melted plastic seat of Flanders (1961–62), which reads like a Bernini gown as cast by Matthew Barney then thrown over a Francis Bacon papal throne. The raw despair of the piece testifies to Foulkes’s sensitive nature, since he went “over there” nearly ten years after the war.

By the mid-sixties, he was working in a monumental mode, with large paintings of butchers’ diagrams and anatomically textured rocky landscapes. The random letters and numbers had become handwritten words, gestures toward the postcard, missives from a mythic, evacuated West. The irony was emerging, however, behind the Pop icon making.1 The rock paintings took off, sending him to biennials abroad and almost getting him to believe again in his childhood love—surrealism. But success was apparently pathogenic to him, and he couldn’t bear to stick to the formula of his best-received work. So he started making the disturbing portraits that mark the beginning of his mature aesthetic. They began as scalped and bleeding self-portraits and evolved into mutilated heads of geometry teachers, corporate fat cats, art dealers, and politicians. Obscure symbols—triangles, dollars, industrial appliances, mail—disfigure their faces. They are zombie martyrs of fifties authority, bearing cartoon hats or hands, clutching money, extending out of the frame.

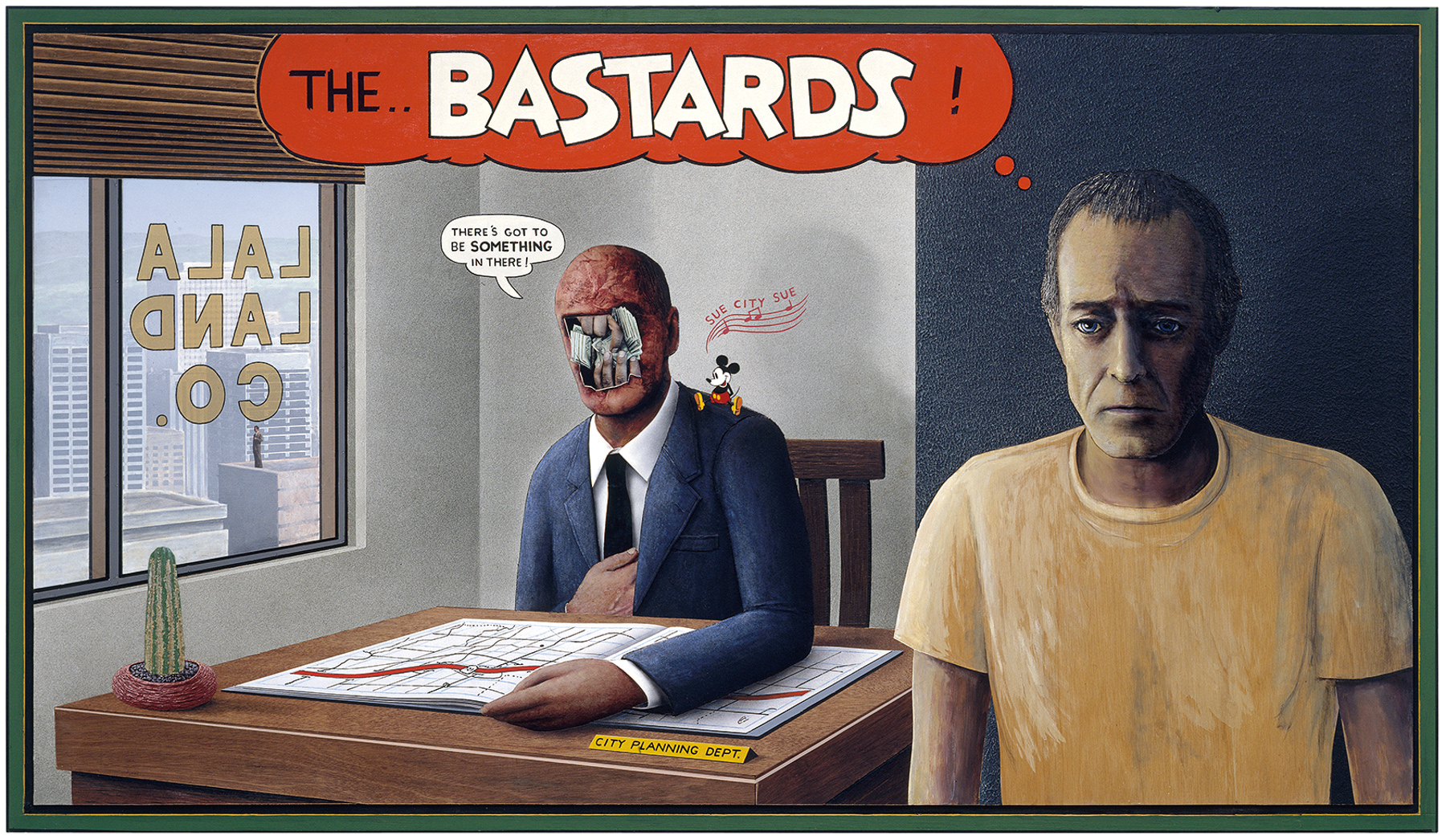

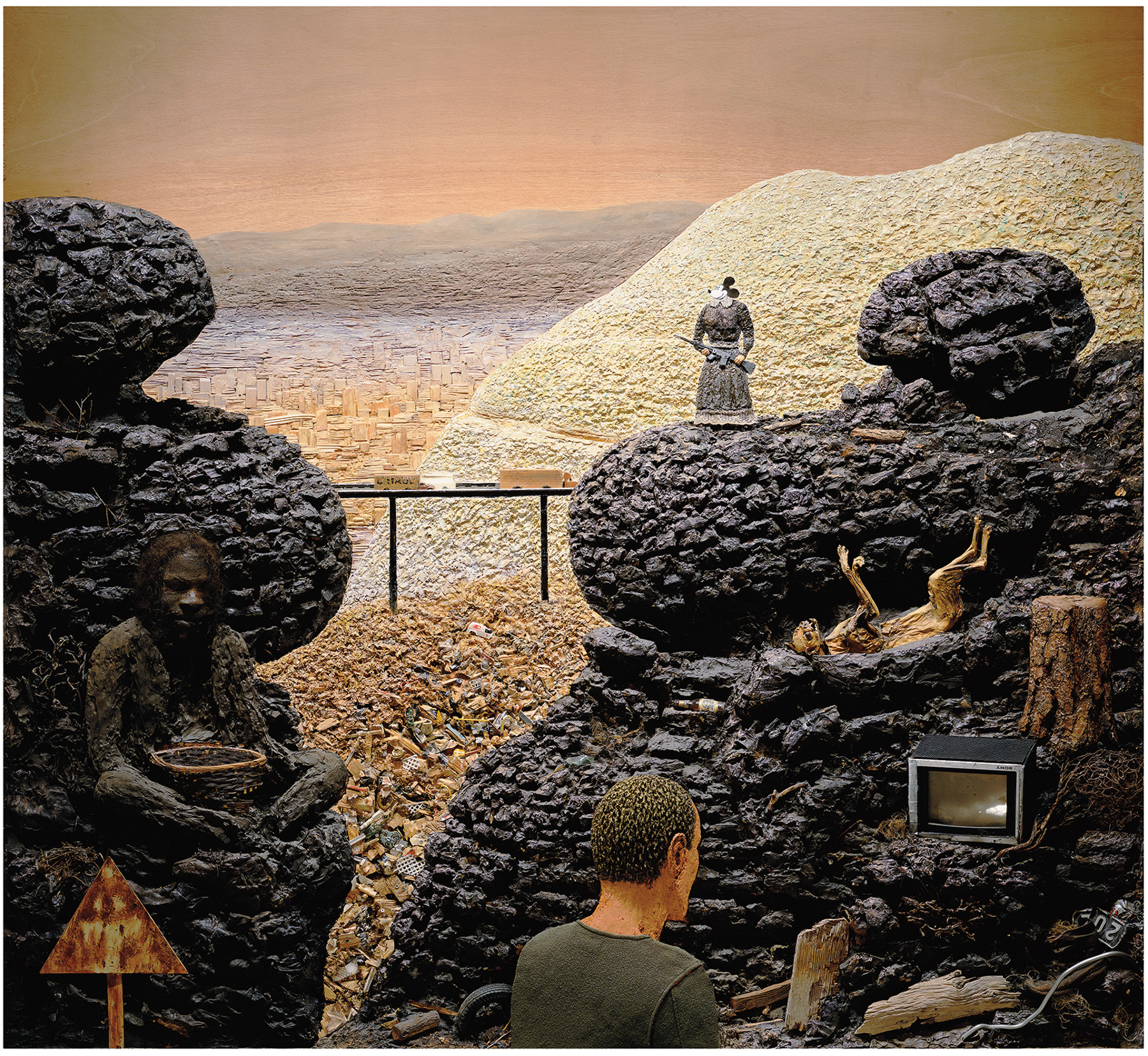

The scale soon broadened out to large, craggily impastoed tableaux of sad sacks trapped in denuded landscapes, thick with trash and guns and con- fused or dead wildlife, tortured by insinuating (but also charming and some- times befuddled) cartoon characters, principally Mickey Mouse (or Mickey Rat, as Foulkes calls him, for either childish or legal reasons).2 These later pictures are crude and graphic, cartoonish in both their technique and their politics. (Some, like The Rape of the Angels (1991), a broadside aimed at evil real estate development, even feature thought bubbles containing impotent oaths: “The bastards!”) More than one depict superheroes bereft of their brio, guns fallen into the wrong hands, natives mummified in place, televisions stupefying their watchers, or “For Sale” signs plunked into Western vistas (or, as in For Sale [1995], spray-painted behind a roughhewn cross). In the wasteland of Old Glory (1996/2001–3), the American flag is limp, but the Golden Arches stand tall. Even the titles—The Corporate Kiss (2001), But I Thought Art Was Special (Mickey and Me) (1995)—are sophomoric accusations of hypocrisy and betrayal, making the corporate takeover of America a source of tinny, adolescent outrage. The villains and victims are clear.

Llyn Foulkes. The Rape of the Angels, 1991. Mixed mediums, 71 × 54 inches. Private collection. Image courtesy of the artist.

Foulkes’s outrage, however, does not offer the same safety to its owner as the Hammer’s tour guides. There is no distinction, in his late work, be- tween caustic self-portraiture and angry allegory, between hating the world and hating the self. It is the artist outside the picture that puts the artist (or one of his faux-superhero proxies—“Artman,” Clark Kent) inside the picture, and reveals him to be petty, ineffectual, and probably unhygienic. Foulkes shows us how shabby his clothes are getting, how gray his skin, how bug-eyed his gaze. This creates just enough sympathy to draw the viewer’s attention to the fine touches—the cracked perspective, the con- trolled sense of color, the range of accomplished textures. The explicit commentary of the pictures still seems crude, but the condition of their maker achieves a human scale that includes the viewer. His puerility is made to seem like innocence, and emasculation like universality.

3. The Eraser

Foulkes’s was not the only recent survey exhibition that generated this experience of the “anti-sublime”: intense fear and attraction produced by works lacking all grandeur. The Santa Monica Museum of Art presented Joyce Pensato’s first solo museum show, after thirty years of work. If Foulkes became a fringe character because of his fragile, self-mocking probity, Pensato became one because of an essential mismatch between her milieu and her particular talent. Trained in the atelier of Mercedes Matter’s New York Studio School, she was neither terribly interested nor terribly skilled at the still life and figure painting she was doing there. The school promoted the idea that the traditional drawing technique that drove the Western tradition was expressing itself in the pure abstract painting of the time, in the likes of Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, and Pensato’s mentor, Joan Mitchell. Against this heady backdrop, disillusioned by her own forays into abstraction, Pensato was forced to find something less transcendental, something truer to her native backwater Brooklyn.

Llyn Foulkes. The Lost Frontier, 1997–2005. Mixed mediums, 87 × 96 × 8 inches. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Guston, with his famous AbEx apostasy, consciously or unconsciously became the key. At the Studio School, Guston was “our God,” Pensato says,3 and indeed his example, if not his prodigious way with paint, is a lodestar and prototype for the entire tendency that connects her work and Foulkes’s. Like Guston, Pensato turned her formalism toward the exploration of a more personal visual interest. Despite having little interest in comic books as narrative or television as entertainment, she had always loved copying cartoons. She replaced the Studio School’s live model with a flatter subject, entirely reliant on proportion and line for its visual power—that is, a giant, life-sized cut-out of Batman. So began thirty years of mining the simple and insane power of cartoons.4

The work in the exhibition was almost exclusively large-scaled and black and white, either smudgy charcoal drawings or drippy black enamel paintings. All the interwar icons whose silhouettes suffice to convey their identities were represented (Mickey Mouse, Felix the Cat, Donald Duck, Groucho Marx, Batman), as well as several of their more recent parodies and tributes (Stan and Cartman from South Park and the cast of The Simpsons). The effect takes the gestural drips of Jackson Pollock and the powerful intervals of Franz Kline and yokes them to a cultural power so brilliantly visual and yet so inherently stupid that it feels like the brainwashing that so disgusted Foulkes. In this sense, Pensato is a true contemporary heir to Guston, but with the color and invention (and sheer painterly brio) stripped out. She might have titled one or more of them “Erased Guston.”

Joyce Pensato: I KILLED KENNY, installation view, Santa Monica Museum of Art.

Photo: Monica Orozco.

Nonetheless, they are images that communicate their full power face-to- face, rather than in reproduction. This is an interesting point of commonality with the particular AbEx mode in which Pensato was trained. The Studio School promoted the idea of mark- and shape-making that draws the viewer into a visual field, influenced by Hans Hofmann’s notion of “push and pull” space as opposed to Renaissance perspective. This approach led to rich abstractions whose spatial nuance registers best in person, but it also seems to have created, in Pensato, cartoon characters in whom humorous flatness has been replaced with unsettling dimensionality, when the works are seen face-to-face. This uniqueness in each work, the variegated space created by the marks and drips of an individual gesture, generates their most productive irony, in fact. Mickey Mouse is, after all, designed for mass production, for instantaneous and irresistible imprint—on screen, on stuffed animal, on giant costume head. But Pensato’s messy characters are unique and convey their full menace only in person.

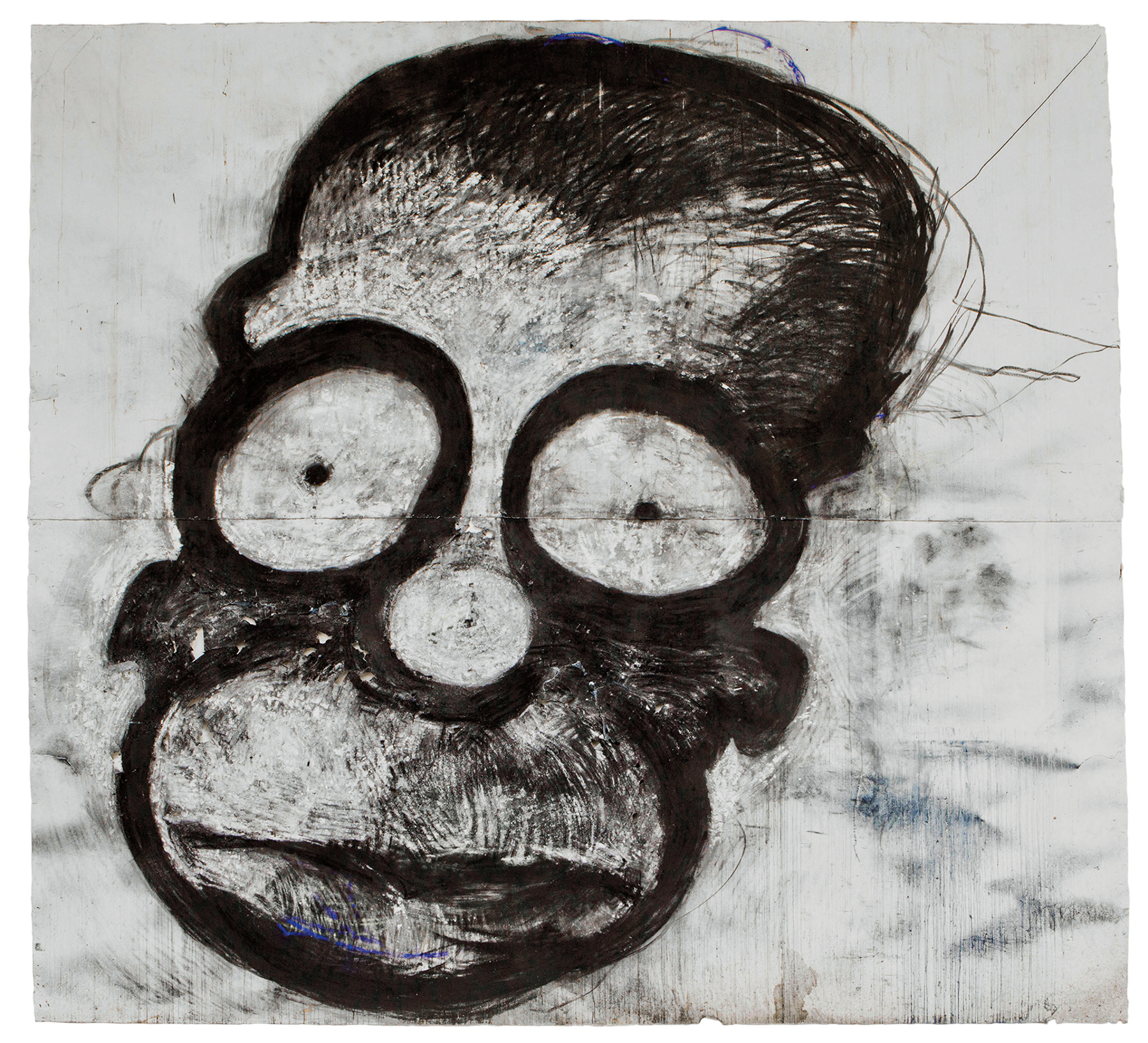

And they do menace, with an alarming variety of incompletely sublimated social ills. If Foulkes was piling up a defense against his own pop-cultural superego, Pensato is erasing her way down to our collective id, as expressed in the pap we feed our children. The enormity of the anxiety these happy little icons hide is startling even for a viewer conditioned by a Foulkes-esque cultural resistance. Her versions of these characters remain sufficiently close to their originals’ proportions to feel like assimilations rather than adaptations or appropriations. Thus, paradoxically, it’s as if their true natures have been revealed rather than their likenesses exploited for new critique. Pensato uncovers Mickey Mouse’s smutty avidity, Donald Duck’s rictal commerce with himself, Felix the Cat’s saucer-eyed existential nausea, Cartman’s bleary depression. And oh, the blackface of the clown! In other shows, she’s made explicit photographic reference to Al Jolson, but it’s not necessary—she shows you its shambling, thick-lipped resonance in Mickey, in Homer Simpson, even in Stan from South Park. Homer Simpson is Pensato’s particular muse; in her hands, he’s all dark bulges and pinpoint irises, strung out, wobbly, tilted and distended in the forehead—but, crucially, not nearly as dumb as he acts. Pensato understands the improvisatory relation between line and persona as well as any animator—and she coaxes from that one element a full human music.

Joyce Pensato, Large Homer, 2006. Charcoal on paper, 120 × 131 inches. Courtesy of the Artist;

Petzel Gallery, New York; Galerie Anne de Villepoix, Paris; Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago. Photo: Monica Orozco.

It is a strange use of pop culture, and as with Foulkes, not a confident one. She talks in interviews about having learned (with the help of psychotherapy and feminist icons) to “accept” herself as a “big mess,” to “own her situation,” but she also sounds as if she’s protesting too much, as if the project of personal self-acceptance remains unfinished.5 She is drawn to uneasy messes of comedy and terror—a wall collage at the SMMoA show juxtaposes a tough-gal Gena Rowlands (from Cassavetes’s Gloria) with a spatter-painted Abraham Lincoln, and gives central attention to the famous close-up of Jack Nicholson’s manic grin from in The Shining. In that context, Jack suddenly looked, no alteration needed, like a tiny Joyce Pensato painting, and not like the dorm-room shrine of a thousand undergraduates. It made an icon of irony into a personal matter, a simplification of one mind rather than a culture.

Pensato and Foulkes both refuse to recast their twisted representations as alternative icons, to portray them at a scope beyond the individual. The artists’ work gestures at critique, but refuses to be pinned down to a thesis, containing just enough expressionism to carry emotional weight and just enough Dada to cover its ass. Whether this is cowardly or prudent is hard to resolve, but it is shrewd. The artists know better than to try to create some new greatness. Their work suggests an often sappy belief in Art as Monument, but it rarely cops to any belief that a work of art might still become a monument.6 Forced by circumstances to think in simple pictorial terms, their work constitutionally provokes suspicion about that simplicity, and must immediately use those dumb terms against it. These artists live, therefore, in limbo, failing to own or disavow their assertions, except the one that says that mainstream culture is a perverse joke compared to which art is small consolation.

4. If She Didn’t Exist…

If you wanted to invent a character to embody the next phase of this sensibility, one tickled rather than hurt by the demise of American goodness, you might conjure up a bricoleuse who haunts thrift stores seeking the totems and fetishes of high American optimism. You might have her rename herself after a vintage movie star. You might have her grow up in the sleepy suburbs of Los Angeles. You might have the novelistic imagination to send her out to modernist Palm Springs on the weekends, to feel the uniquely Southwestern contrast between the unreconstructed natural hostility of the desert and the digestible romance of high kitsch, in the land where the Gabor sisters lived.

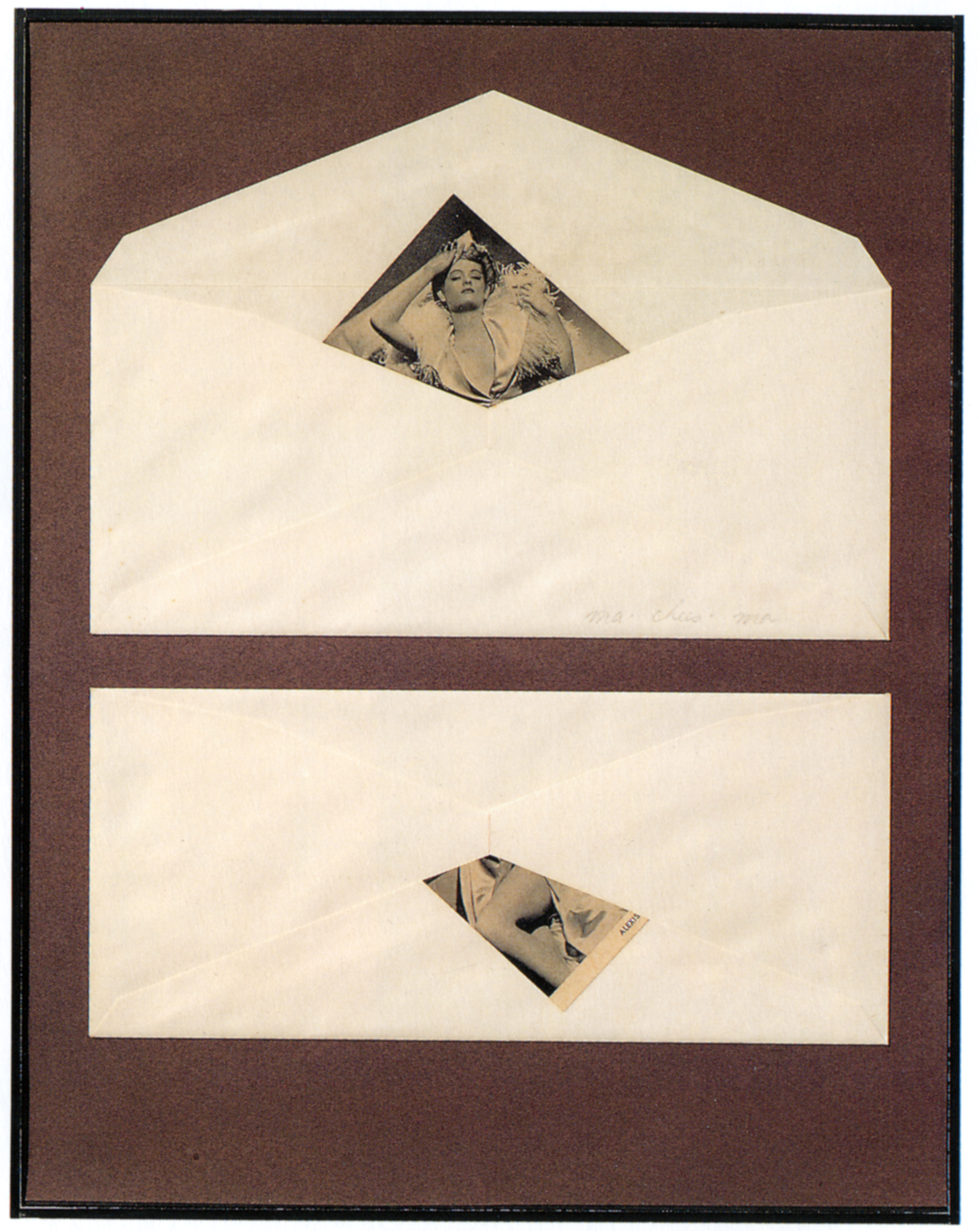

You might even have her announce her artistic coming-out with a simple collage that interweaves a plain business envelope with a pin-up shot of the aforementioned movie star, carefully cut and placed so as to obscure her midsection with the envelope seams. It’s possible you’d even cleverly title that work Ma-chees-ma (1971). But you would never in a million years find it plausible that the actual aforementioned movie star would actually buy that very piece for her own art collection! It’s too much, they’d say. Life imitates art; it doesn’t usually serve as its accomplice.

Alexis Smith, Ma-chees-ma, 1971. Paper collage, 14 × 11 inches. Collection of the actress Alexis Smith.

Therefore, it is slightly more forgivable than it might otherwise have been that the artist Alexis Smith’s friend, the poet Amy Gerstler, in a coy faux-biography that accompanied the catalog to her Whitney Museum mid-career survey of 1991, paraphrased Voltaire and cast Smith as God. “Luckily for us,” Gerstler wrote, “[Smith] sprang into existence somehow. If she hadn’t, we would have had to invent her.”7

Born a nearly a decade later than Pensato and a decade and a half after Foulkes, Smith claimed for herself the divine confidence of self-invention, a blank rear-view in a Western expanse. This means that she doesn’t have the burden of expectations as a source of disillusionment, but it also means that she doesn’t have any fixed recourse to culture at all. Her irony neither frightens nor embitters, but it also doesn’t always hit home. There is no home.

Smith, too, has had a late-career resurgence in Los Angeles. After a six-year hiatus, she has had five solo shows in four years here, at no fewer than four separate galleries. This past year, it was at Craig Krull and Honor Fraser, which together contained a mix of new work and old, including a re- installation of the moving 1989 Santa Monica Museum of Art installation Past Lives, a collaboration with Gerstler.

Like Pensato’s, Smith’s mode has been fairly consistent over the years. Collage is her medium, and the frisson of ironically deployed nostalgia is her most reliable message. Where Foulkes is densely anxious and Pensato is mentally diagnostic, Smith is drolly suggestive. After Ma-chees-ma, her early work consisted of serial paper collages that resembled musical scores or typescripts and unfolded narratively. They began fairly highbrow, probing sizable passages of Walt Whitman, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Thomas Mann, Edwin Abbott and Jean Cocteau, along with fairy tales—Beauty and the Beast, 1001 Nights—with cut-outs and backgrounds, stencils and ephemera, in effect creating her own mysteriously illuminated manuscripts.

These projects both expanded in form and declined in subject, as she created large and often trompe l’oeil installations, essentially hypertrophied versions of her most clever collages, and began to treat her texts, too, as magpie material, rather than foci of primary, or even sustained, attention. The cut-up magazines, pulp novel covers, doilies, tchotchkes, and advertisements no longer punctuated empty expanses of typewritten manuscript; they took them over and colonized them. Her punch lines were now pictures, and words were no longer the standard against which visual ideas were measured, but instead just another tool for their mysterious association. As the Whitney curators noted back in 1991, she moved slowly but surely from literature to cliché, from text to image. In fact, as in Pop art—Ed Ruscha comes most readily to mind—the art began to treat the words as images, just as advertising had long done.

Smith’s interests overlap Foulkes’s and even Pensato’s: the Western landscape, patriotism, guns, cigarettes, brands, Mideast war, the Bomb, consumerism, the ways that companies use our yearning for mythology against us, the dumb things people on TV say.8 But Smith’s jokes are wittier than anything in Foulkes or Pensato, and often safer, communicating not psychological emasculation or anxiety but high-concept amusement. There are moments, however, when Smith shows teeth, as in the 2002 piece Degree of Difficulty, which posits a ski-slope grading scale (and geometric relationship) for our media-driven notion of feminine sexual identity, ranging from the easy vulgarity of a Vegas-style escort handout (the porn star’s genitals obscured by a green dot—beginner), to pop star and Pepsi shill Britney Spears (her eyes covered by a blue square—intermediate), to daffy actress, New Ager, and AARP magazine cover-girl Shirley MacLaine (nose and mouth muffled by a black diamond—expert). What this scale means, or rather, where its lasting values lie, is just short of clear, but it’s about as close as Smith gets to pointed criticism.

Alexis Smith, Degree of Difficulty, 2002. Mixed media collage, 25 × 20 × 2 inches. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures.com.

But Smith also has a somewhat wider purview than Foulkes or Pensato. For one, she more readily tackles questions of money, class, and race. Much of her work, based in advertising, mocks consumer aspiration or assuming an identity based on material accouterments. Even as she pokes fun, though, Smith is more forgiving than Foulkes. There is undoubtedly an aspect of Pop joy in each use of dated glamour; she revels in the ravages of time on consumerism, and in her ability to hint at some occult escape from it, using only the garbage it leaves behind. She rescues throwaway pleasures and tacky follies and extracts one last thrill from them. The layers upon layers of it all delight her, and us too.

Smith’s work repeatedly questions, as Gerstler puts it, “the assumption of a coherent underlying American mythology,” and even of “the blind, blanket assumption that what happens in the world can be organized into some kind of ultimate meaning.”9 This distinguishes her work from Pop art, which may not have intended to stand for ultimate meaning, but in its choice of appropriations relies on the possibility that such an American mythology could exist. In other words, it exploits the very idea of commodification that gives Llyn Foulkes such a headache. “Whether such notions were/are terrible lies, or components of a viable belief system, or sweet delusion,” Gerstler continues, “Smith is too wise to ever try to definitively state.”10 Pop art chose a side—sweet delusion!—but Smith is stuck in between.

5. Ironography

All three of these exhibitions in Los Angeles11 were greeted with stories about the artists finally getting their due. Collectively, they made for a better than average survey of a single tendency, not just because of their similarity, but because of their range within it. They covered the gamut of the formative period for the tendency, whose artists seem to be mostly born from the mid-1930s to the late forties. They covered the East and West Coast flavors of this art. They moved, in chronological order, from bitter disillusionment with the myth of unified culture, through dark psychoanalytic unmasking of the myth, to blithe nonchalance about its nonsensical persistence.

Does this common spirit, this personality of art, need a name? The lens of a term would surely reveal other artists working in the mode, or connect artists already well known. As Gerstler noted of Smith, the mode seems connected to the post-war tendency of mass media (television in particular) to promote, then immediately undermine, the grand illusion of a unified culture, of Americanness as one shining thing. More specifically, it subverts that pop-cultural monotheism even as it depends on its power, sitting heavily on its cliché like a Magritte castle on its cloud. It curdles the Pop aesthetic, creating a sour, emotional postmodernism, rather than the light, sweet, thinky confection we’re more accustomed to. This postmodernism has no confidence; it takes everything personally. It’s not serious, but not joking either.

As a matter of art history, its line emerges from the connect-the-dots rambling of beatniks and Funk Artists, reaches its zenith in the high paranoid style of the Reagan Administration, and by the Internet Age seems to have influenced, and possibly dissolved into, a weak stew of winking memes, hipster t-shirts, and refrigerator magnets.

That potential dissolution is a problem, when it comes to naming. If anything defines the movement, it’s a suspicion of generalization and doubt about how naming leads to selling. Labeling the movement would surely miss the point. Surely an artist like Foulkes, with his anti-corporate, anti- capitalist bent, would insist that the project not be tagged and that the artist never become a brand.12Still, would a shorthand not be useful?

Let’s call it Ironography, and cast it as the addled, conspiracy-theorist bastard child of Pop, an ironic update of the long art-historical tradition of iconography. If the awkward neologism or the way classification can be tantamount to condescension causes discomfort, we can at least say that this discomfort is one instance of the defining feature of Ironography—a nauseating stasis between two incompatible impulses. Gerstler says that Smith is too wise to say whether an American mythos is viable or not, and that seems right, but it’s also true that she’s too weak-willed to decide. Ironography is an art of no lasting conviction. Instead of elevating kitsch to high art, and thus making itself vulnerable to further irony, it wallows in kitsch and renders any purchase on it permanently slippery. Its historical basis is painting, but its central mode is collage, or at least the suggestive juxtaposition of found imagery, distorting the contours of pop culture to reveal something simultaneously sinister and ridiculous. Smith is its consummate practitioner, in this sense. She often combines text and picture, but the text is ineffectual—useful primarily for its aura of mysterious relation to the pictorial rather than its conceptual power—in the manner of an album or magazine cover.

Ironography frequently takes as its pictorial subject the lowest of the low, the branding accessible by even children, the signs aimed at capitalist transcendence, requiring no language, no culture, no history, no folklore. It depicts not the flag but the logo, not the myth but the cartoon. It is encrusted, stained, and faded—no industrial silkscreens or Ben-Day dots here—and mostly poorly or summarily designed, hard to read, homemade- looking. It’s not that technique is beside the point because concept is king; it’s that technique requires the continuous confidence of un-ironic principle.

This seems a good moment to note that the irony I’m talking about is not merely semantic irony, or pictorial irony—presenting the opposite of what is meant—but also a kind of psychological or subjective irony, a kind of schizoid dramatic irony, in which the artist as speaker is unaware of what is happening in the picture, exactly. This sense of artistic ignorance, even artistic failure, is calculated, meaning that the artist actually is aware of her not knowing, or appearing not to know. Indeed, she has set the work up to communicate the fact. But it’s also anticipatory (she knows that her take will be partial, ungodlike, but this is the best she can do) and vague (she recognizes her predicament, but she still doesn’t know exactly what it all means). Everyone is totally aware, but still, nothing is known.

Thus the unstable—or actually stable and permanent—nature of the irony under this heading. It doesn’t just incriminate the guilty, it obviates all possibility of innocence or transcendence. The layers lift the work by its bootstraps, until it floats before you in a stance of no real politics. The viewer can’t shake the sense of knowing something, of seeing something, that the artist does not, of seeing the artist’s complete partiality, and yet both already know this to be false. The viewer doesn’t know what it means either, just that it’s sad, cheap, or scary. It’s the visual equivalent of the form in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest—the virtuosity accumulates despite the clumsiness, and uncertainty persists not despite but because of the total self-consciousness. It won’t speak, won’t decide, because it is paralyzed.

6. Wild Horses

In her “fictional biography” of Smith in the Whitney catalog, Gerstler hinted at one further corollary of the not-my-place-to-say, raising-questions-is-enough school of art making. “What’s invaluable about Alexis Smith,” she says, “is not what we can ferret out or devise about her history. It’s what her work continues to reveal about how we think and live, about the collective American unconscious.” Never mind that the “collective unconscious” would be precisely the sort of “organized” and “ultimate meaning” that Smith’s work supposedly rejects. The larger implication is that the artist, in her particulars, doesn’t matter. Not just that biography is not the key, but that identity doesn’t relate except accidentally. Smith herself doesn’t make this claim. But the art sometimes seems to suggest that its creation has been a matter of pure sensibility, allowing the artist the distance of irony with only a tangential responsibility. In reinventing herself and disowning the past, she frees herself from bitterness even as she assures a certain superficiality.

Alexis Smith, Wild Horses, 2012. Mixed media collage, 22 × 42 inches. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures.com.

Gerstler’s claim stands in opposition to much of what has been published about these artists over the years, up to and including this essay. Like the Hammer Museum guide in the Foulkes show, much of the writing about this work has focused even more than usual on the artists’ biographies, on their real or invented personal lives. Their works’ eccentric ironies seem to draw attention to their deeper motivations, where the Warholian strain of Pop does the opposite—insisting that persona is constructed entirely on the surface.

This must suggest that there is a deep connection, in forms of contemporary unease, between identity and culpability. To believe in the self is to promote a lie and suffer continuous disillusionment. Foulkes certainly makes the positive case to match Smith’s negative, and Pensato affords to pure Pop characters an individuality that, in some sort of divine retribution, puts them in our shoes.

There was one sign in the Honor Fraser show that Smith might be headed toward another fruitful reinvention. Above the reception desk was a recent collage entitled Wild Horses (2012), simpler than the rest, consisting of a schlock painting of wild mustangs with the Patti Smith EP Set Free pasted in its corner, the singer peering out from a feral squat as the horses run her down at full gallop. Those who know that Alexis Smith’s real first name is Patricia, and that she formerly went (reluctantly) by Patti Anne, might be tempted to think she is gesturing toward a lost authenticity, her abandoned identity, through another act of name-appropriation. If so, maybe reclaiming herself as Patti Smith would imply that one could pass through irony into a belief in meaning again. Maybe the next phase of Ironography will actually be wisdom, a settling down. But maybe not. Maybe wild horses couldn’t tear her away. Either way, one feels the need to invert Voltaire’s quip, the one Gerstler applied, to get at the implied humanity beneath Smith’s archness: if we can’t invent her, she must already exist. Gerstler was right to make it a matter of religious faith. Ironography may not believe in us, but we can hardly doubt its existence all around us, coloring our vision and conditioning our faith, or lack thereof. It is an idol offering no salvation that we can’t help but worship.

Ian Chang is a writer living in Los Angeles.