Tim Eitel, Mondrian (mit gelb), 2001. Oil, acrylic on canvas; 150 x 200 cm. Sammlung Queenie, München. Courtesy Galerie Eigen + Art Leipzig/Berlin and Pacewildenstein.

The German artist Tim Eitel, a prominent member of the so-called “New Leipzig School” and co-founder of the Liga collective art gallery in Berlin, has featured prominently in what is often referred to as the revival of figurative painting. Uneasy with descriptions of his work as “cold,” with “vast,” “empty” landscapes and disengaged protagonists, the artist sees his work as a form of deep engagement with the material and psychological conditions of modern life.

Born in 1971 in the southern German city of Leonberg near Stuttgart, Eitel briefly studied German language, literature and philosophy at the University of Stuttgart from 1993–1994. In 1994 he enrolled at the prestigious academy Burg Giebichtenstein in Halle, and in 1997 he began his artistic training at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig, graduating from Arno Rink’s master class in 2003. Eitel has been awarded numerous prizes and took part in the International Studio Program at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin.

His work has been shown in museums and galleries in Germany, the United States, Switzerland, France, the Czech Republic, Denmark and Israel. In 2005-06, his work gained visibility in the United States through a solo show at the Saint Louis Art Museum and a travelling exhibition organized by Mass MOCA, as well as a group exhibition mounted at the Cleveland Museum of Art. His latest body of work was exhibited at PaceWildenstein in New York from November 17, 2006 to January 20, 2007.

Dorothea Schoene

Dorothea Schoene: What influenced your decision to choose the Leipzig Academy?

Tim Eitel: To look beyond my own limits. I went to Halle [in Eastern Germany] to study painting in 1994 and everything in the East was new to me then. For me it was especially interesting to experience such a completely different lifestyle than in Western Germany [where Eitel grew up].

DS: With a certain image of this place already in mind?

TE: No, not really. I went on a little excursion around East Germany in 1992 and visited the various art academies there. I did this based on the feeling that the academy in Stuttgart, which I already knew, wasn’t the right place for me. Somehow, I couldn’t agree to this whole attitude in the West German academies—this idea that you go to the academy and try from the very beginning to distinguish yourself as an artist. My ideal was rather to take a slower path, to slowly approach things without the pressure of having a strong and interesting artist profile from the start. That was at the end what I found in the East. These decades of walling-off had preserved something, the whole thing was something like an oasis.

DS: Leipzig also has the reputation for very good technical training. Was this part of your master class training with Arno Rink?

TE: It is something of a myth that you learn these great technical skills in Leipzig. As if they are non-existent elsewhere. This surely isn’t true—you learn to draw elsewhere as well. And learn how to prime a canvas. The only difference is that there was—and this has probably changed since—a 2-year basic training in which you did nothing else but nature studies, and that was definitely something other academies didn’t do.

DS: Leipzig is home to the so-called “Leipzig School,” a movement often understood as very “German,” not only because the artists are trained exclusively in Leipzig, but also because much of the work adheres to a certain style which has its roots in Leipzig and the location’s history.

TE: Painting is in principle more strongly connected to the past than other art forms, such as video art for example—because video has a way shorter history than painting. On the other hand, there are also local mannerisms that emerge simply because of a certain environment in which you live and which leave certain impressions on you, as well as the fact that you live in a certain artistic environment, which somehow influences you as well.

DS: So it is rather a “local aesthetic”?

TE: It is difficult to really categorize it. Something that always troubles me when dealing with the “Leipzig School,” is that everyone assumes you got your entire inspiration, your style, from it and they ignore what happened before you got to Leipzig. I, for example, went there and studied at the academy for 5 years, though I was “aesthetically socialized” way before that of course. I never experienced what living under a socialist regime was like and coming from Western Germany I grew up with completely different influences than somebody from Leipzig. I think these years of growing up are very important for the direction your idea of art takes.

DS: Your work provokes a broad variety of responses and comments, but it is often seen as rigorous, distanced, and cold. Do these words describe well what you aim for with your work? Do you see the aesthetics of a motif before the choice of the motif itself? How do you approach your work?

TE: It is probably an inner necessity to create work in accordance with oneself. And I have realized that my work has changed, that my topics and my coloring have evolved. This already began in Berlin, but I became aware of other things here in the USA than I would have realized in Berlin or in Germany, simply because I think that here the extremes of Western civilization clash so obviously. And that of course influences you. [Eitel spent 2005 in Los Angeles, 2006 in New York and now lives and works in Berlin.]

DS: So you illustrate your topics with the use of color?

TE: Of course.

DS: After your stay in Los Angeles, you replied to a question about how this residency influenced your work, and you remarked that you won’t start painting palm trees. Do you see an influence at all?

TE: A very strong one. You usually have these palm trees in mind as the essence of Los Angeles. But for me the homelessness in downtown seemed more essential. It was so shocking for me, since I had never seen something like this before. The fact that this big urban area, this massive city, doesn’t know what to do with all these people. That the authorities gather them in one tiny place—downtown. There they dump all the homeless people they pick up in the LA area and then they have to live there.

DS: At the same time, Los Angeles is also a very dazzling city.

TE: It is also a very nice place to live. This makes the extremes even more extreme. It’s different here in New York, where the differences clash more directly, while in Los Angeles they remain separated. A film producer with his mansion in Westwood might have never seen these things.

DS: Do you show this experience in your work?

TE: Yes, this is prevalent in my recent works.

DS: Your working method is based upon taking pictures and extracting details from them not as a complete photo-realistic transposition, but as an excerpt.

TE: Well, I usually compare this to traditional sketches. I take snapshots, without looking for a special photo. I photograph a motif or figure that catches my eye and interests me. When I paint a picture, it is then that I compose—I find a figure interesting and search for something that goes together with it. At the end, the work is put together from different sources.

DS: Do you identify photography as an influence on your work or is photography simply a tool, as you said, that you use like sketches?

TE: The medium of photography plays an important role of course, since it allows you to capture moments you could otherwise not capture—simply because of the speed of the camera. But at the same time, it is difficult to distinguish, since the artistic process is influenced by a number of things—things that have influenced me, such as film, commercials, media in general and art history.

DS: Is there a need to express your cultural identity in your work, or does cultural memory play a role in the way you paint, in the form you give your paintings? For example, you often refer to Baudelaire—can you explain this reference and your understanding of his writings in regard to your work?

TE: One thing that interests me in Baudelaire’s essay about the painter of modern life is that he argues that every historical period finds its own forms. They are expressed in every aspect of life—attitude, fashion, clothing, forms of conversation and how houses look. This aesthetic surface expresses the époque. On the other hand, he sees a second element—the eternal. But Baudelaire realizes how hard it is to capture the eternal, how hard it is to define. It’s all about beauty in his essay, but beauty itself is again a difficult concept, a combination of multiple things and has something contingent to it.

DS: To come back to the notion that every historical period finds its own forms, there is currently an exhibition in Los Angeles of works by Caspar David Friedrich and Gerhard Richter that implies that the roots of Richter’s work rest in the ideas and forms of Friedrich.

What do you think of this attempt to derive a lineage from Friedrich to Richter?

TE: I haven’t seen the exhibition, but I always find these things very questionable. I have been compared to Friedrich myself. And I never liked it. But maybe Richter liked the idea.

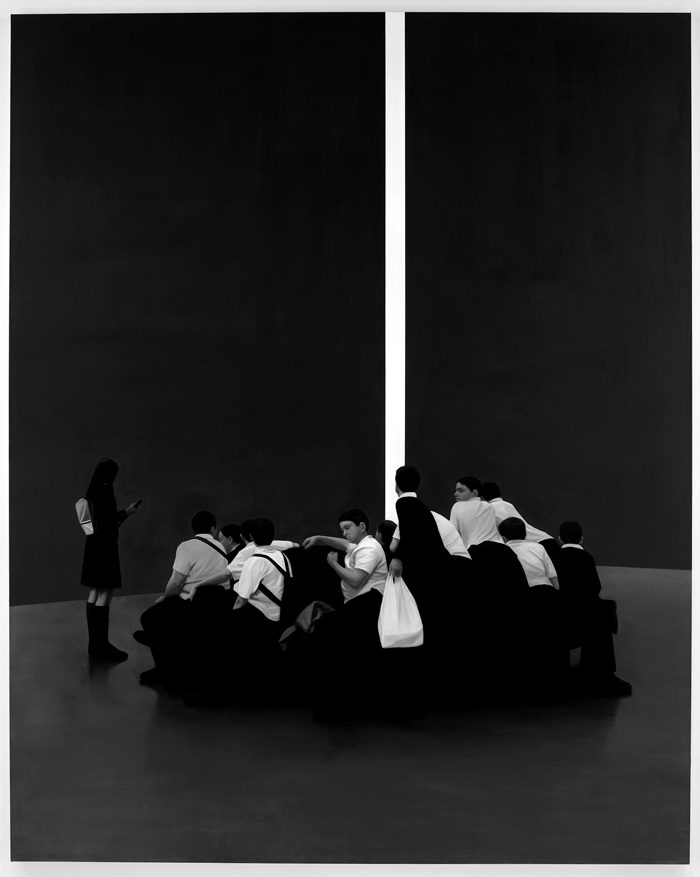

Tim Eitel, Öffnung, 2006. Oil on canvas, 274.3 x 219.7 cm. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Eigen + Art Leipzig/Berlin and Pacewildenstein.

DS: So how would you characterize your interest in the Old Masters?

TE: There is always this habit in art history that one tries to categorize things and to compare them, or to insert them into a line of tradition. Of course there is always a reference to another image in an artwork, simply because artists look at other artists’ work and are influenced in one way or another by it. Sometimes you even find a direct reference or something like it. But I usually find this procedure is overvalued in the interpretation of an artwork. For me, this is not what makes a painting interesting, if there is a tiny link to Caspar David Friedrich or any other artist. But for many art historians it is a proof that the artist is very conscious about his medium if he appears to quote other artists.

DS: So what is your motivation then for looking at Old Masters? Is there a humorous element to it? If you quote Mondrian—as you have done—but in doing so exclude the ideas of world improvement that underpin his work, what does this quote or reference mean?

TE: Well, first of all I want to emphasize that my work and my attitude towards this subject has changed over the years. These early works were really meant to be direct references to Mondrian. At that time it was about positioning myself somehow—trying to locate myself artistically. At that time I dealt a lot with museum interiors—trying to examine where works of art hang and to analyze the spaces of and for art. In this way I was able to deal and play with problems of space and traces in space, and to define them for myself. On the other hand, Mondrian was a fixed idea of mine. He fascinated me because of the extreme contradictions his work embodies: that one creates this totally rational, almost lifeless structure, behind which you find this utopian theory of salvation. This is a strange idea—that a lattice and some colors can improve mankind.

DS: These political or educational concerns are not part of your work—at least not in a straightforward way.

TE: This is of course a question of definition. I am not interested in an educative aspect, but I do see a political element in my work. Maybe it is a social rather than a political element—even though these are often synonymous.

DS: Is your work a way to represent your generation? In the majority of your works, you depict young people. Is it your aspiration to capture a generation or the aesthetics of this age group?

TE: In my opinion, one should only paint things one knows, and not indulge in things one doesn’t know anything about.

DS: Do you feel as an artist that you have a certain responsibility? Do you believe as an artist you have a particular role in culture—to entertain, to enlighten, to document or to criticize through your art? Does something like this exist for you?

TE: Yes, of course. One’s primary responsibility as an artist is to be faithful to your own work. You try to produce what you see as good art, though this always depends on your attitude about what good art is, of course. I am not a person who says that art in general should simply make people happy, or that art should enlighten people politically or whatever. There are so many possibilities, what art can be and what it can do. I always find it highly questionable when people try to define a single role for art.

DS: Can you describe the phases in your work that you have already mentioned in passing? Can you give us some kind of perspective on your current and future challenges?

TE: The beginning is something I already described talking about the Mondrian paintings. After that I began with landscapes as a way to escape from the strict geometries of interior spaces and at the same time to free myself from this very self-reflective practice. I wanted to get away from this strict art context that always played a role in my work, that’s why I moved to landscapes. Even today I think that these early phases in my work still matter and are present in my most recent work. For me, these changes are some kind of slow broadening of my perspective, that I can do other things without loosing sight of my starting point. After the landscapes came something that I still have trouble finding words for, even though I have been thinking about it a lot. Maybe it is the idea that my images stand like symbols or signs for our time. They result from this entire cosmos of things we see—like TV and movies—all of these surfaces, the world of images that influence us. The difficulty is bringing this world of images together with what really exists out on the street. This is the edge I am working on.

DS: One fascinating aspect of your images is the strong emphasis on perspective and space, but never—or hardly ever—on a recognizable space. Do you aim for arbitrariness in locating people and things? And do you see a connection between that and what makes other people see your work as cold, distanced, etc.?

TE: That’s an interesting point. My paintings have something to do with the fact that we are surrounded by so many images, but we cannot fully decode them as language. My images are open and closed at the same time. You have to read them as images—it makes absolutely no sense to analyze them linguistically. My painting is not narrative in a traditional sense either. Instead, some kind of interaction takes place, which makes sense—visual sense. My painting makes sense as an image and not as a narrative. This is probably what most people find so difficult when they “bounce” against the image and say that linguistic analyses don’t give them a way to enter the work.

DS: In the end, this may not be attributable solely to the limitations of language as an analytical tool, but also to the fact that your work often embodies a process of intense self-reflection. What seems to linger in the work is this existentialist idea of the “I,” which establishes a distance between the object and the viewer that cannot be overcome easily.

TE: This distance is of course always there, but this is at the same time an interesting thing for me. I talk a lot with people who see my work. And I often hear that people want to “read” my work. This is due to the fact that they do not approach the paintings by asking, “What does the artist want to show me?” and instead ask “What is the story?” I believe that my works are instead an offering; it’s the world as I see it. And the real goal for me is to activate something in the spectator. It all depends on whether the spectator is willing and able to activate their own “image archive,” because it really depends on the interaction between the image offered up in the painting and those in your head as a viewer, and what you make of the connections.

Dorothea Schoene received her MA in Political Science and Art History at the University of Leipzig, Germany, in 2005. In 2006 she received a Fulbright grant to study at the University of California in Riverside, CA. Presently, she is enrolled at the University of Hamburg pursuing her PhD in Art History. She is currently working as a Research Assistant at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, preparing an exhibition on German Art during the Cold War, 1945-1989.