A Telephone Conversation between Harold Gregor and Damon Willick, April 12, 2011

Damon Willick: I must say that revisiting Everyman’s Infinite Art has been a pleasure for me. However, I am unclear about much of its history and hope that you can shed some light on how it came about.

Harold Gregor: First off, I really did close the door of Purcell Gallery and walk away. We had a lot of fun back then doing things like that, and your call has inspired me to rethink my time at Chapman almost forty-five years ago. It’s been fun to resurrect Everyman’s Infinite Art. I have a copy of the catalog in front of me now.

DW: Great. Let’s start with the basics: What led to the staging of the exhibition? What were you doing at Chapman leading up to the show?

HG: I started at Chapman in 1966; I was head of the art department and was responsible for the gallery. Chapman was much smaller then than it is now, much different than today. The art department was located on the second floor of a building with a big room designated as an art gallery. The faculty consisted of Bill Boas and Jane Sinclair, and each of us was responsible for staging shows in the gallery throughout the year.

There were standard shows that we had to put up like student exhibitions and what not. I had only been at Chapman for about four months when I did Everyman’s Infinite Art. Prior to that I had finished my doctorate in painting at Ohio State University in 1960 and had taught at San Diego State and Purdue Universities. My formal training was in art history, aesthetics, and philosophy.

During my time at San Diego State (1960-63), I had befriended John Baldessari. He was one of a dynamic group of young artists coming up in San Diego, and I was greatly influenced by that art scene. In 1963, I was offered a position at Purdue University in Indiana to help start their doctoral program in painting, and I taught there for three years (1963-66). In 1966, I accepted the position of department head at Chapman and taught there for four years before moving on to Illinois State University, in Normal, to establish a doctoral program in studio art.

Before I arrived at Chapman, I had been involved in Conceptual art activities like trying to autograph the San Andreas Fault line and the Route 66 dividing white line as long drawings and other things like that. I was interested in signing things, and more and more I started to become interested in fundamental questions about the nature of art and how one differentiates an art object from non-art.

I was teaching a class at Chapman at the time on aesthetics and had a really good group of students that were open to exploring these issues with me; we’d take field trips to the beach and make paintings in the sand that I considered to be “field paintings.” We’d shovel sand and make holes and take photographs of our work and discuss what was the art: the labor, the hole, or the photograph. We were exploring the line between art and non-art.

When the Carl Andre brick work, titled Lever, was shown at the Jewish Museum’s Primary Structuresexhibition in the spring of 1966, it really struck a chord with me.

DW: How did you first encounter Andre’s work and the Primary Structuresshow?

HG: I am not certain, but I think I first read about it in Artforum. The photograph of the 137 firebricks aligned on the floor was of interest to me. When I saw the photograph of the work, all of the questions about art versus non-art that I was exploring really came to the fore. What I didn’t really pick up on in the photograph was the role of the viewer in Andre’s work; that the viewer stands within the piece directly. The room space in Andre’s work was part of the work.

I used Andre’s Leveras a discussion piece for my Chapman class and with other colleagues to start to devise objects that could balance between the divide between art and non-art.

DW: So you read Andre’s piece as non-art. Did these discussions about Andre’s work with your class and colleagues lead directly to Everyman’s Infinite Art?

HG: Yes. Since we had to have an exhibition mounted for Christmas break, I figured this could be the show. So, we went ahead and constructed our proposals. One thing that was great was that I had the local hardware store donate the supplies for the exhibition; Mr. Boon Johnson of the Double J Hardware Company was a really nice guy, and he gave us the galvanized steel nails and the yard sticks for free. We returned all of the material to him after the show was over, because they weren’t really used at all.

During our discussions, the students came up with the list of requirements that each piece had to satisfy, and we followed the instructions in our construction of the art/ non-art objects. I wish I could remember the students’ names, but it’s been some time since the show. Mike Rogan is the only name that I can recall; who knows if he’s even alive? I know that a few of my students back then are no longer living. I am 81 years old now myself.

DW: It sounds like you were sincerely interested in exploring these art/non-art issues in the exhibition, and were not just parodying the Primary Structures exhibition. Did you think of the Everyman’s Infinite Artas aligned with the history of Conceptual art activities that go back to Duchamp and Dada and had reemerged in the 1960s?

HG: Yes! If somebody had noticed that back then, I would have been quite happy. I was also painting at the time; I’m a painter by training. And I had some recognition doing installation pieces, getting an NEA grant in 1973 to do floor pieces using corn meal. But that was a bit after I left Chapman and had relocated to the Midwest.

In 1968, while at Chapman, I did participate in the Rauschenberg E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology)show at the University of Southern California, with Dave Walkington, the horticulturist. The piece entailed cacti and paint.

DW: Getting back to Everyman’s Infinite Art, can you talk about the language that you used in the catalog? The wording seems to anticipate both the critical attacks on Minimalism by the likes of Michael Fried as well as the directional instructions of such Conceptual artists as Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Huebler, and others. Were you aware of how prescient your writing and ideas were at the time?

HG: No, that’s just the way I write.

DW: Okay, but your statement at the end of the catalog, where you say that the works of the exhibition need not be viewed or even produced, points directly to Lawrence Weiner’s Statements, where he proclaimed similarly that his ideas need not be made. You seem to predict what many consider to be groundbreaking Conceptual art.

HG: Yeah, sure, I’ve thought about this, but I don’t think those artists knew about what I was doing.

I did meet Carl Andre, though, through the Tom Jefferson Gallery in San Diego. Tom knew Andre, and he brought him to the Chapman Gallery and we spent the afternoon together. And, boy, he was really disturbed about Everyman’s Infinite Art.

DW: This was after the exhibition had closed?

HG: Yes.

DW: Where had Andre heard about the exhibition?

HG: I had sent out 500 copies of the catalog by mail. Chapman had an extensive mailing program, and I used the college’s generosity to mail my catalog to many different locations to get some attention for the gallery and school. Grace Glueck of the New York Timesactually reviewed the exhibition because of my mailing. She gave the show quite a nice review, too. The artist James Byers also responded positively to the work, and agreed to be a visiting artist at Chapman because of the exhibition.

DW: Why was Andre upset with the exhibition? Do you think that he thought of the show as solely making fun of his art?

HG: Yes, I think he did. He was not very friendly to me, that’s for sure.

DW: Did he misread your seriousness about the exhibition as being an investigation of art and non-art objects?

HG: Yes, the exhibition was a serious consideration about art. I did this with students, remember, and I wanted them to question what can be art; I used Andre’s work as a starting point for my students to do something similar in order to explore these issues directly. The more we worked on these questions, the more interesting our proposals became. I wanted to get to the fulcrum point of making objects that could be considered art or not. I liked highlighting all of the considerations that one had to go through to answer whether or not an object could be art.

The class came up with some other really great art projects beyond Everyman’s Infinite Art. For example, they buried a long dynamite fuse in sand and lit the fuse so that sparks burst erratically out of the ground. The students made an 8 mm film of this. They also covered two different sized battery cars in zebra stripes and had the smaller one search out the larger one throughout the gallery. There was something really poignant about the smaller car chasing and searching for the other one. I don’t know if I’m describing this too well, but it was really a great work. The chasing went all day long. These are just a few of the student projects that came after Everyman’s Infinite Art.

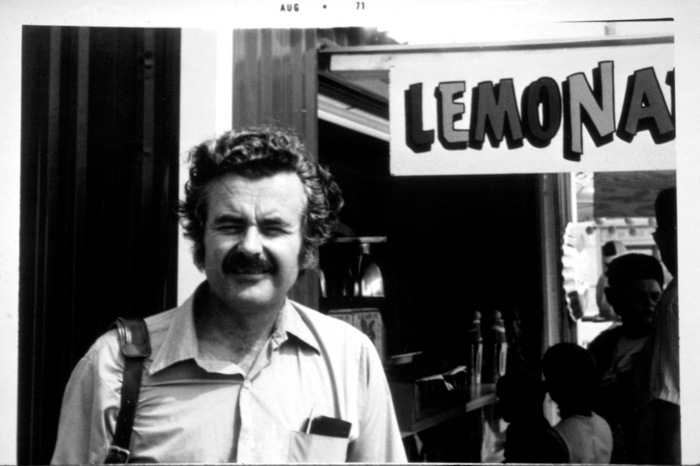

Harold Gregor, 1971. Courtesy of the artist.

DW: This all took place at Chapman College in Orange County?

HG: Yes, in December 1966 and into 1967. It was in 1967 that Andre visited Chapman.

DW: How did the Chapman administration and other faculty respond to these class projects?

HG: The faculty were really supportive, the president not so much.

DW: At the time, did you see your activities in relation to other Southern California Conceptual artists?

HG: Sure. I saw Ed Kienholz’s Watercolorsexhibition at the Eugenia Butler Gallery up in Los Angeles. I thought those “money works” were really intriguing. It was a great time to be an artist in Southern California. It wasn’t New York, but then again, New York is interested in New York and not many places other than that.

Harold Gregor gained national prominence in the early 1970s within the Photorealism movement, turning to farm structures and the sweeping horizon of the rural Midwest for inspiration. Among many distinctions, he is the recipient of a 1993-94 National Endowment of the Arts grant and a NEA Midwest Fellowship. In 1993, he was awarded the Illinois Academy of Fine Arts Lifetime Achievement Award. Gregor’s work is represented in important public and private collections throughout the United States and Europe. Gregor is Distinguished Professor, Emeritus, at Illinois State University, Normal.

Damon Willick is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at Loyola Marymount University and serves on the editorial board of X-TRA.