In the wake of a presidential race characterized by cultural wars, demands for compromise-averse representatives, and choices from an ever more narrowly cast and biased array of media sources, I wonder what role art has played amidst this cultural break-up. Are enough artists working to challenge people’s outlooks, encourage free and open public dialogue, and cultivate tolerance? Are artists fostering the willingness to debate that is so necessary for the realization of such goals? Or, are they part of the problem, making works that “preach to the choir” no less than political bloggers and pundits?

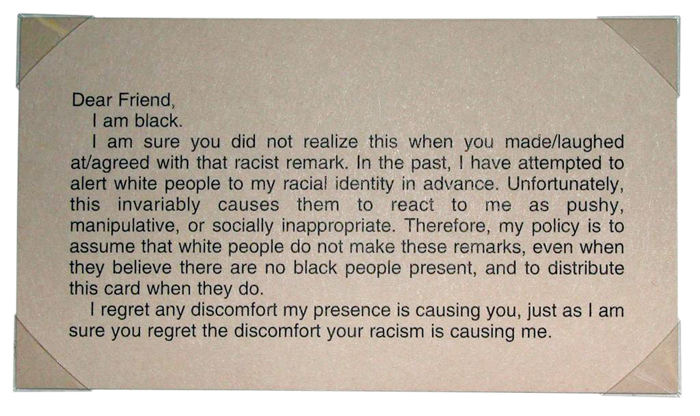

I specifically ask these questions of audience-participatory, or “interactive,” art because in this genre the art’s audience is also the artist’s medium. Take, for example, Adrian Piper’s now classic work, My Calling (Card) #1 (1986). At a social gathering, Piper presented a pre-printed card that stated: “Dear Friend, I am black. I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark….” as a pointed rebuke to perpetrators of this type of comment. In this piece, Piper’s artistic medium was not so much ink on paper as human interaction. More than any other kind of art, the interactive stands or falls with the specificity of its social relations. We should assume, then, that it is fair to scrutinize the entire genre on these terms. Nevertheless, my questions focus solely on interactive artists who use their art to promote democratic ideals.

Adrian Piper, My Calling (Card) #1, 1986. Performance, business card; 2 x 3 1/2 in. (5.1 x 8.9 cm) each. Courtesy of Adrian Piper Research Archive.

The use of interactive art for this purpose is justified by the theory of democracy. In particular, the attempt to change minds through collaborative exchange, rather than spectatorship alone, finds support in the ideal of citizen deliberation. Theorists of “participatory” democracy such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the eighteenth century, John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth, Jürgen Habermas in the twentieth, and today’s Cass Sunstein have stressed that active and civil give-and-take among people of differing views is a bedrock of informed and socially responsible citizenry.1 In democratic society and democracy-promoting art alike, the deliberative model is well worth upholding because engagement with diverse, if sometimes irksome, points of view is essential to our sense of shared humanity. Through it, we acknowledge our collective interdependence.

That model of democracy, however, is buckling under increasing stress. Since the mid-1970s, but more acutely since the 1990s, the populations of leading industrialized nations have been experiencing balkanization. As I will soon expound, people have been self-segregating further and further into clusters of the likeminded through where and how they live, how they think, and how they communicate and receive information and opinion. In order to reinforce profitable niche affiliations, marketers have concomitantly exploited the trend by cultivating a fragmented landscape of media usage wherein people avoid dissonant information and opinions.

Confronting this anti-democratic tendency is not the sole responsibility of artists. Yet, democracy-promoting interactive artists cannot afford to ignore it. If they do not enlist ideologically diverse participants in their (inter)activities, their works cannot live up to their potential as agents of deliberation. Artists who want to have a democratizing impact should evaluate their methods in light of this challenge. Do they stand up to democracy’s latest threat—fragmentation?

The goal of this paper is to make observations and suggestions regarding artistic methods that address conditions hostile to deliberation. I hold up strikingly different works by Adrian Piper and Michael Rakowitz as equally promising models. In addition to Piper’s aforementioned My Calling (Card) #1, I refer to Rakowitz’s paraSITE (1998-ongoing), for which the artist designs and distributes lightweight, inflatable shelters for homeless participants. In addition to evaluating Piper and Rakowitz’s methods and strategies, I also point out counterexamples from the recent history of interactive art. When it comes to countering balkanization, many otherwise canny works reveal common methodological missteps. Before any discussion of method can take place, however, it is necessary to define the scope and mechanisms of our social fragmentation. The magnitude and seriousness of its challenge to artists demands elaboration.

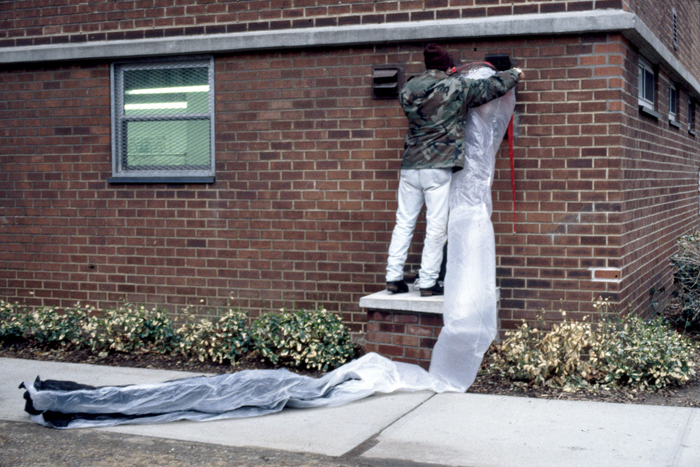

Michael Rakowitz, Bill Stone’s paraSITE Shelter, 1998. Plastic bags, polyethylene tubing, hooks, tape. Cambridge/Boston, MA. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

BALKANIZATION AND THE RISE OF ANTIDEMOCRATIC INTERACTIVITY

Approximately thirty years ago, an artist could have been reasonably confident that a spontaneous sampling of people on a busy street would produce an ideologically diverse audience. No longer. Researchers of demography and migration patterns have noted a clear pattern of self-segregation over the past thirty years. Studies by Richard Florida and Bill Bishop, for example, have recently shown that in the United States fault lines of education, income, age, race, religion, and tolerance of immigrants have been exacerbated by voluntary geographical clustering.2 One result is a remarkable political homogenization within local communities. In The Big Sort (2008), Bishop concludes: “In 1976, less than a quarter of Americans lived in places where the presidential election was a landslide. By 2004, nearly half of all voters lived in landslide counties.”3

The causes of clustering along geographic lines are deep-rooted, complicated, and multiple. What matters more for our purposes is that the pattern is self-reinforcing. As social psychologists have long understood, homogenous groups become, over time, more extreme in their points of agreement and less tolerant of difference. Simultaneously, the trend toward marketing goods and services to increasingly smaller sub-sections of the population—“niche marketing” or “precision marketing”—has evolved alongside geographical clustering, further aggravating its separatist effects.

Michael Rakowitz, Michael McGee’s paraSITE Shelter, 2000. Plastic bags, polyethylene tubing, hooks, tape. 26th Street and 9th Avenue, Manhattan. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

The key to exploiting social divisions is media segmentation.4 Pivotal to that segmentation are marketers’ tactics of “tailoring.”5 When initiated in the 1980s, tailoring was limited to encouraging customer loyalty through incentive programs that customized prices, opportunities, and information to individuals. Since the 1990s, tailoring has expanded dramatically, becoming paradigmatic of contemporary communications. The popularization of Internet usage has made tailoring an exponentially more powerful tool of media segmentation. The interactivity of the Net makes it easy and commonplace for people to tailor information and products to themselves while simultaneously being the subjects of targeted marketing.

Since the early 2000s, our commercial and political lives have become inundated with interactive tailoring. It doesn’t take much to participate—willingly, reluctantly, or unwittingly. If you’ve ever used a credit card, registered a purchase, or registered yourself on a website, or if you’ve ever given personal information in order to get a discount or make a purchase, online or face to face, then you’ve been watering a growing field known as “database marketing.” Once you’ve been digitized, you can be tracked across various sites from your snail-mail magazine subscriptions to calls you make by landline or mobile phone to the GPS technology in your car. Beyond these baselines of input, there are greater and greater levels at which you participate in information tailoring as you visit your iGoogle homepage, customize news and entertainment feeds, blog, or otherwise contribute to the sea of information and opinion on the web. That information is then combined with other data about you, including how you use the web, to enable marketers to further customize types of appeals and media content to you.

Michael Rakowitz, Michael McGee’s paraSITE Shelter, 2000. Plastic bags, polyethylene tubing, hooks, tape. 26th Street and 9th Avenue, Manhattan. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

Joseph Turow denounced these digital-marketing practices as culturally divisive in Niche Envy (2006). Marketing insiders Bernice Kanner and David Verklin took an affirmative tone in Watch This Listen Up Click Here (2007). Yet all agree on the mechanisms by which marketers help us steer ourselves into media cocoons. In this process, we are “pulled” toward customizing our own media content, as when we create preferences on websites or become drawn to them in the first place by savvy precision marketing.6 Simultaneously, more personalized content is “pushed” toward us. Marketers of commercial and political content alike push ads and other messages to people based on information marketers have about them, which is derived from people’s own inputs. Such “mass customization” is working every time Amazon.com or TiVo suggests books or programs you might like. It is also a growing trend in digital advertisements and product placements. Examples include the cable company Comcast’s Adtag and Adcopy software and the even greater-customization-capable, real-time-operative Intellispot software which, Turow notes, “could seamlessly send an African-American household a car commercial with an African-American female driver while it sent a Korean-American household the same commercial with a different price incentive and a Korean-American male driver.”7 These various trends in tailoring erode the common cultural frames of reference on which a deliberative democracy thrives.

In the context of political campaigns, tailoring shows its destructive impact on democracy directly. Individual households regularly receive solicitations from political campaigners designed to appeal to them based on what market research reveals about their preferences, what issues they prioritize, and to what language and imagery they are receptive. Bill Clinton’s 1996 presidential campaign success was credited in part to his shrewd use of micro-targeting to address voters in particular “lifestyle clusters.”8

Michael Rakowitz, Michael McGee’s paraSITE Shelter, 2000. Plastic bags, polyethylene tubing, hooks, tape. 26th Street and 9th Avenue, Manhattan. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

Refinements of micro-targeting for the 2004 presidential campaigns amplified social differences and consolidated the likeminded. Based on interviews with Bush/Cheney strategists, Bishop observed that the campaign intentionally departed from the deliberative model and moved toward increasing turnout among those already inclined, based on research into their other preferences, to vote for George W. Bush. Pursuing a “friends and neighbors” strategy, they facilitated convivial social events among those listed as belonging to certain church groups, hunters’ groups, and among people who signed petitions such as to outlaw gay marriage. The campaign directed canvassers not to try to persuade or argue with people.9 A PBS documentary on branding and market research, The Persuaders (2004), offers more evidence of social-mirroring tactics. Door-to-door campaign workers for an undisclosed presidential campaign customized palm-pilot video messages.10 Racial segregation had taken a technologically sophisticated and precisely calculated turn, as the documentary showed one black woman presenting another black woman with a video clip of a third black woman campaigning.

In the 2008 presidential race, the friends-and-neighbors strategy of 2004 escalated with the first extensive use by candidates of web-based social-networking devices drawn from Myspace.com and Youtube.com models. The candidates’ websites, where supporters steered their conversations into geographical and ideological enclaves by blogging and threading, gathering “friends,” and inviting neighbors to house parties, offered ample opportunities for people to organize and segregate themselves.

Legal scholar Cass Sunstein argued in Republic.com 2.0 (2007) that the tendency toward intensification of sameness within homogenous groups, known in social psychology as “group polarization,” is alive and well in what he refers to as people’s pervasive “filtering” of their various media inputs on the web.11 The echo-chambering Sunstein found in studies of web activity has also been demonstrated in newspaper media. In 2004, University of Chicago economists took a measure of bias in 377 newspapers accounting for seventy percent of U .S. daily circulation. Liberal or conservative “slant” correlated strongly to the 2004 political affiliations of readers in their zipcodes.12 Sunstein’s larger point is apropos here, too: the unprecedented power of the individual to filter—to avoid engagement with disagreeable content or contrary points of view—jeopardizes democratic culture.

I am not nostalgic for fewer media options. Today’s access to information and opportunities via digital, networked media should be democracy’s dream fulfilled. Indeed, it sometimes is. But I recognize that filtering, in combination with tailoring, yields stagnation and complacency—gated communities and ghettos of the mind.

In effect, we are afflicted with the rise of an antidemocratic culture of interactivity. An unconstrained yet relentlessly manipulated free choice corrodes our potential for citizen deliberation. Contemporary market and media segmentation both force our hand and help us help ourselves to become more and more like ourselves and dismissive of those not like us. In an ironic historical wrinkle, participation itself—so vital to democracy and interactive art alike—is the friendly face of democracy’s new foe.

ARTISTIC COUNTER-INTERACTIVITY

If we really believe, and I do, that art can be an agent of democratic deliberation, we owe it to art and democracy to revisit art’s methodological readiness for this challenge. The population in any given locale is far less random and ideologically diverse today than artists of a former generation could assume. In their efforts to mitigate social segmentation, how artists select audiences for participation in artworks is paramount. Also of utmost importance will be whether or not artists devise terms of interaction that are likely to prick social bubbles.

Several stratagems that have already been in development over the now several decades long history of interactive art should be salvaged for today’s counter-segmentation needs. To illustrate them, I highlight two exemplars of these methods. The first, by Piper, is from an era that pre-dates the deluge of data mining and tracking, but continues to be methodologically instructive; the other is a more recent work by Rakowitz. Their examples have wide-ranging implications for interactive art because together they straddle the spectrum of interactive art developed so far. They encompass its commonly recognized range of categories: the “interventionist” mode that favors surprising unsuspecting audiences and what Grant Kester has dubbed the “dialogical” type, which relies upon cooperative relations with its audiences. They span both confrontational and collaborative practices, single-audience and multiple-audience works, and the short-lived and long-term artwork.13

A set of critical criteria is needed for producing audience-participatory projects. I propose the following rubric, which I have devised to apply to any attempt on the part of interactive artists to resist balkanization.

1. Choose audiences that are likely to be surprised by the points of view or insights represented in or by the work.

Situate the work in physical or media sites where desired audiences are likely to congregate but will not expect to encounter opposition.

Adrian Piper’s My Calling (Card) #1 offers one model of savvy contextualization. As soon as one or more participants at a social gathering made a racist remark—mistakenly assuming that he or she was amongst likeminded individuals—Piper would hand the offender a small card showing a typed, paragraph-long statement making them aware that Piper is black. The card proceeds to explain with acerbic wit why Piper has resorted to handing out a card in situations such as these: “In the past, I have attempted to alert white people to my racial identity in advance. Unfortunately, this invariably causes them to react to me as pushy, manipulative, or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are no black people present, and to distribute this card when they do.” Impeccable timing and a captive audience maximized the impact of her gesture.

A very different but equally effective approach to audience selection is exemplified by Rakowitz’s paraSITE. This complex work involves targeting several audiences to play differing roles in the work. The practical goal of paraSITE is to craft easily made and readily transportable shelters for distribution to homeless people. Although the shelters take a variety of shapes, sizes, and interior architectures, all are built with tubular extensions for easy attachment to the air vents found on the exteriors of buildings. This crucial piece of the design, which explains the work’s title, allows the impromptu shelters to be heated by an otherwise unused resource, the output of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

To design these shelters, Rakowitz sought the input of some of the homeless people who would be using them. At a municipal center over several months in 1998, he met with several homeless men, including Bill Stone, George Livingston, and Freddie Flynn, whom he approached after noticing them on his way to his graduate studies at MIT. Rakowitz’s various modifications over time to the shelter designs reflect their feedback and that of other collaborators. According to Rakowitz, the men saw these shelters as a form of protest—a way to make themselves and their plight more visible.14

The work guarantees surprise among each of its several audiences, and, at every turn, uses it pointedly as a catalyst for cross-niche awareness or exchange. The homeless men must have been initially wary of Rakowitz’s approach, though the shock surely abated as they entered into collaboration. The “hosts” are surprised to find their passive but crucial role in sustaining the homeless men via their unwitting donation of HVAC waste. Finally, passersby are taken aback by the shelters’ theatrical disruption of the routine streetscape, and may be compelled to consider their own privilege.

2. Avoid requiring specialized knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, or tastes to apprehend the work if doing so prevents audiences’ exposure to information or viewpoints outside their social niche.

Piper’s art avoids this impetus toward segregation by making reference only to the racist remark and doing so with pinpoint timing. Her audience is thus guaranteed to perceive Piper’s reference to the offensive speech as a disruption to their false sense of community. Taking a different tack, Rakowitz’s work requires no specialized frame of reference for anyone familiar with the presence of homeless populations on urban streets, even if interpretations of the work may vary.

Komar and Melamid, America’s Most Wanted, 1994. Oil and acrylic on canvas, dishwasher size. Photo: D. James Dee. Copyright Komar and Melamid. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Many works that are otherwise thoughtful about audiences do not crack any ideological cocoons because they do not challenge the sociologically meaningful audiences. A prime case is People’s Choice (1995) by the well-known, U .S.-based Russian duo Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid. For the project, Komar & Melamid hired a market research firm to survey diverse audiences in the U .S. to find out what were the most and least desirable characteristics in a painting. (For related projects, they surveyed citizens of other countries.) The results—recreations of the “most” and “least wanted” paintings—comprised People’s Choice. According to the project website, Komar & Melamid were asking their audience to consider, “What kind of culture is produced by a society that lives and is governed by opinion polls?” And, “What would art look like if it were to please the greatest number of people?” I agree that these are worthwhile questions. However, the problem is that the work can be perceived as critique only by audiences already socialized to find the resulting pictures mediocre clichés. The many contributors to the survey, who may have answered earnestly that their favorite color in a painting is blue and their favorite subject a landscape, are not invited to ponder the deeper questions at stake because their participation is limited to the survey. Thus the work’s payoff is at their expense, not for their benefit.

3. Construct scenarios and terms of interaction that encourage people to adopt, accept, or simply become aware of a viewpoint outside of their social niche.

The key is to disarm audiences’ tendencies to ignore or dismiss dissonant information or viewpoints. Piper did so by taking advantage of her audience’s captivity in an intimate social situation. The offenders could not easily deny the actions for which she held them accountable. Piper also appealed to the offender’s sympathy by making the victim—herself—literally present.

Rakowitz compels us by other means. The ingenuity of the shelter designs and the artist’s sense of humor, as well as visual drama, inspire his audiences to imagine alternatives to normative realities. One is pressed to consider not just instances of temporary housing for the homeless participants but alternative ways of thinking about housing, homelessness, and our interdependence in the world. In addition, the mutual edification of artist and homeless men during the collaborative process installed a basis for trust, empathy, and receptiveness among people normally outside of each other’s social circles. Furthermore, the work’s provocative design and the homeless men’s participation in it as designers and performers allow audiences to envision the homeless men in a different role: as empowered rhetoricians on their own behalf. By combining all of these aspects, Rakowitz employs the best of the two main approaches to interactive art today: the dramatic flair of Situationist-style “interventionist” works and the opportunity for lasting mutual transformations found in the sustained, “dialogical” collaborations between artists and non-artists.

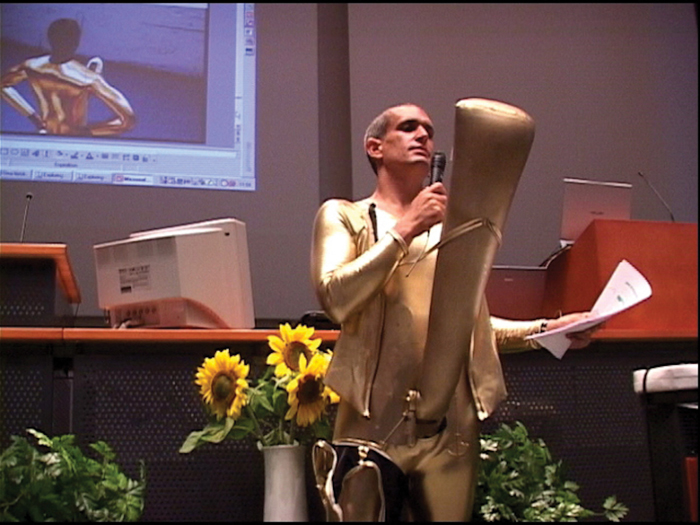

The Yes Men, The Management Leisure Suit, 2001. Performance/intervention at the conference Textiles of the Future, Tampere, Finland. Courtesy of The Yes Men.

Many otherwise democratizing works that do well at audience targeting, and are even skilled at creating socially significant confrontation, still are unable to penetrate audiences’ defenses, and therefore wind up entrenching niches. A case in point is the work of the collective the Yes Men. On a mission to counter the excessive influence and abuses of corporate power within public life, they specialize in forms of counter-propaganda that they term “identity correction.” Typically, these involve sabotage of targeted organizations and individuals via impersonation of their websites—most famously that of George W. Bush and the World Trade Organization. Yes Men members Mike Bonnano and Andy Bichlbaum have also pretended to be representatives of the organizations their websites have convincingly mimicked, attending international conferences and presenting parodic PowerPoints to unsuspecting audiences.

In one infamous case in 2001 at a conference in Tampere, Finland, Bichlbaum lectured on the textile industry as WTO representative “Hank Hardy Unruh.” After punctuating his talk with outrageous claims, including that the abolition of slavery had been pointless in light of the evolution of today’s slave-like sweatshop labor, Unruh augmented the farce by snapping off his business suit to reveal the gold-leotard glory of his “Management Leisure Suit.” Sporting an inflatable three-foot phallus tipped with a video interface system, Unruh demonstrated innovative management techniques. For example, managers could monitor and deliver electric shocks to unproductive workers from a safe and convenient distance.

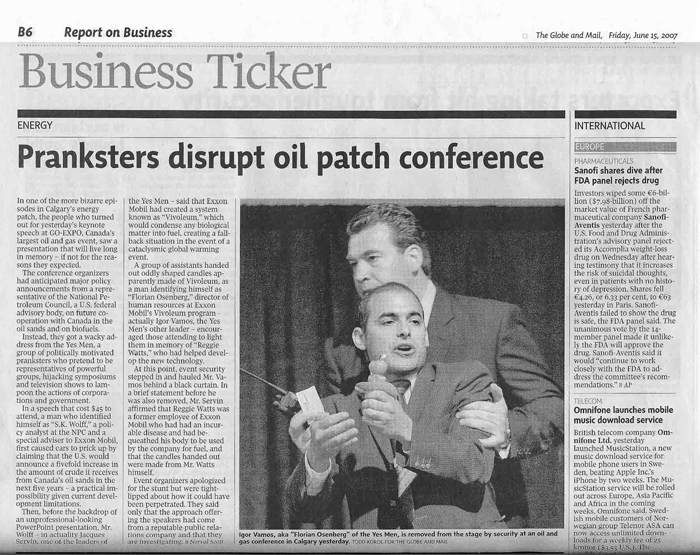

More recently, in 2007 the Yes Men posed as representatives of ExxonMobil and the National Petroleum Council before an audience at GO-EXPO, the main oil industry conference in Canada. Addressing environmental problems produced by oil and coal development, Bichlbaum as “Shephard Wolff” gave deadpan assurances that the oil industry could solve the problem by creating “Vivoleum,” the conversion of human corpses into oil. Again utilizing a theatrical gimmick, the Yes Men passed out candles to audience members. As the lecture wore on, “Wolff” told the audience that the candles they held derived from the willing self-donation of an Exxon janitor who had died while cleaning up toxic waste.

“Pranksters Disrupt Oil Patch Conference,” The Globe and Mail (Toronto), June 15, 2007. Courtesy of The Yes Men.

The Yes Men have few art-world rivals in the realm of comic theater and sheer guts. For these reasons, I admit I am a fan. But social bridges the Yes Men’s antics are not. Audiences’ reactions have been telling. The documentary film The Yes Men (2005) featured footage of the 2001 performance in which, much to the Yes Men’s chagrin, the conferees sat there, even after the phallic management revelation, roundly nonplussed.15 In the case of the ExxonMobil/NPC conference, the artists’ website reveals that the audience reacted the opposite way; they caught on to the parody and became aggressive. The Yes Men were promptly removed from the stage by security guards and briefly detained by the police. The problem with these results is that neither indifference nor hostility opens minds. On the contrary, what they do best is affirm the underlying conflict. The likeminded admire the cunning, courage, and comic skill of the Yes Men’s stunt and appreciate the seditiousness of the intervention. But while the work successfully dramatizes social barriers, it does little to transcend them because it lacks a substantially persuasive aspect. Without an attractive alternative vision, it is too easy for the opposition to dismiss. Removed from the ambiguity of the performance itself and labeled as a prank in the subsequent press coverage that is the Yes Men’s ulterior goal, there is still no motivation for their ideological opponents to consider the substance of the Yes Men’s critique.

4. At least one aspect or phase of the work must be non-voluntary.

The unfettered free choice of information and opinion, as well as purely voluntary participation, is a major source of our current predicament. Voluntary encounters reinforce existing inclinations by definition. In Piper’s case, the offender’s confrontation would not function as such an efficient ethical mousetrap if that encounter were voluntary. The entire work is predicated on surprise. Rakowitz’s work entails both voluntary and non-voluntary parts, but the non-voluntary have crucial significance. The initial approach by the artist to the group of homeless men crossed a class barrier to create an opportunity for dialogue with them. The startling of passersby with the curious sight of the shelters is practically guaranteed to upset the routine of ignoring the homeless on the street in all but the most hardened individuals. Finally, the host’s unwitting contribution to the shelter—a forced, if passive, generosity—crosses a class barrier and makes homeowners or tenants aware of a potential relationship between their consumption and others’ survival. The artist could bring the socially inequitable situation to their attention by asking for their voluntary participation, but the shelters are designed to be mounted and nomadically carried about by the homeless independently—in order to empower them. Should the homeless ask for homeowners’ or tenants’ participation? This too is problematic. Not only might the tenants or homeowners most resistant to empathy under normal conditions be the least receptive to the homeless men’s appeal, but also such an approach would put the homeless in an all-too-familiar submissive position.

The problem volunteerism brings to an art that seeks to transcend social barriers is amply demonstrated by a recent genre of interactive Net art. Its creators tend to see themselves in a pro-democratic vein, for they cast themselves as catalysts of infinite connectivity and universal inclusiveness by their active identification with a similar ethos and practice derived from the Open Source Movement. Such artists make the source code used to construct their Net projects available to users, who are then free to download, disseminate, modify, and create other works from that code—provided that they, in turn, share their work to an equal extent with others. Artists who operate in this communitarian vein see the global scale of the Internet as an opportunity to build utopian communities free from the exclusionary rules of the normal commercial economy that thwart equal access to cultural, human, and technological resources.

Creators of such works tend to imagine a potentially infinite population of participants. To my knowledge, none overtly claims a desire to transcend social divisions, but their talk of social liberation via increasing access to resources and circumventing limitations imposed by commercial forces implies that their liberating goal would only be enhanced by its unceasing spread. One established example, OPUS (Open Platform for Unlimited Signification), at http:www.opuscommons.net since 2001, hints at this self-conception in its very title. The Delhi-based group Raqs Media Collective created this work in order to foster “unlimited” creative collaborations. The site also tracks and diagrams each collaborative tangent and its genealogy from the various “source” works that are freely shared and modified by participants.

But just how “open” and “unlimited” are worlds such as these? If nothing is done to publicize the work or lure those beyond the populations already in the grapevine to hear about it or those accessing it through voluntary searches, then works in the vein of OPUS just reinforce the given social organization. The trans-disciplinary field of network theory—which studies the structural and behavioral patterns in everything from social networks to the Internet web to biological phenomena that have a networked character—supports my suspicion. There is little argument among network theorists that even networked structures such as the web, which make infinite expansion and universal connectivity a technological possibility, reveal in practice a biased character. It is as if the “open” rhetoric accompanying such experiments in collectivist art falls prey to a myth of infinite connectivity—akin to the “six degrees of separation” proposition that everyone can be linked to everyone else in the world in just a few steps. While unlimited connectivity is a theoretical possibility, suggested by the evolving technology of the Internet, it is not a sociological likelihood. In cases such as OPUS, the likely linkages will be determined in large part by the “clustering” dynamics of social networks.16

Michael Rakowitz, Joe Heywood’s paraSITE Shelter, 2000. Plastic bags, polyethylene tubing, hooks, tape. Battery Park City, Manhattan. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

5. The non-voluntary aspect or phase of the work must not be so imposing that it in turn becomes anti-democratic, undermining the civility required for democracy.

This means that the artwork should be kept brief and humane, as with Piper’s work of only minutes. Or, if the work has an extended time frame, as with Rakowitz’s collaborations, its non-voluntary phase—in his case, the initial approach to the homeless men or the duration of one host’s HVAC usage—should remain brief and humane. The guerrilla tactics of the anonymous international activist organization Biotic Baking Brigade is (literally) a striking counter-example. Their so-called agents have thrown pies in the faces of their political enemies. At media events, Bill Gates and Mayor Willie Brown, among others, have been “pied.” This terroristic approach to interactive performance art not only serves to entrench social niches, it is also personally violating. The dismissal of the BBB’s social message is not only likely but, in my opinion, justified.

In the end, the difference between successfully luring audiences across a cultural boundary and further compounding segmentation comes down to effective targeting and persuasion—precisely the areas in which marketing has excelled. The fact is, marketers are far better funded and technologically advantaged than most artists, and will undoubtedly maintain their dominant reach in the persuasion business. But I picture artists in the role of Rakowitz’s homeless shelters: imaginative and unexpected, siphoning power from the marketing host while building common ground in spite of it.

Alison Pearlman (www.alisonpearlman.com) is the author of Unpackaging Art of the 1980s (University of Chicago, 2003) and essays on art and consumer culture that have appeared in art, cultural-studies, and literary journals, including Afterimage, Popular Culture Review, and Southwest Review. She lives in Los Angeles and teaches modern and contemporary art and design history at Cal Poly Pomona.