Listen to Leslie Dick reading her text for the X-TRA Online series

Writers Read here.

It is as if the Photograph always carries its referent with itself, both affected by the same amorous or funereal immobility, at the very heart of the moving world: they are glued together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures…

Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see. In short, the referent adheres. And this singular adherence makes it very difficult to focus on Photography.

—Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (1980)1

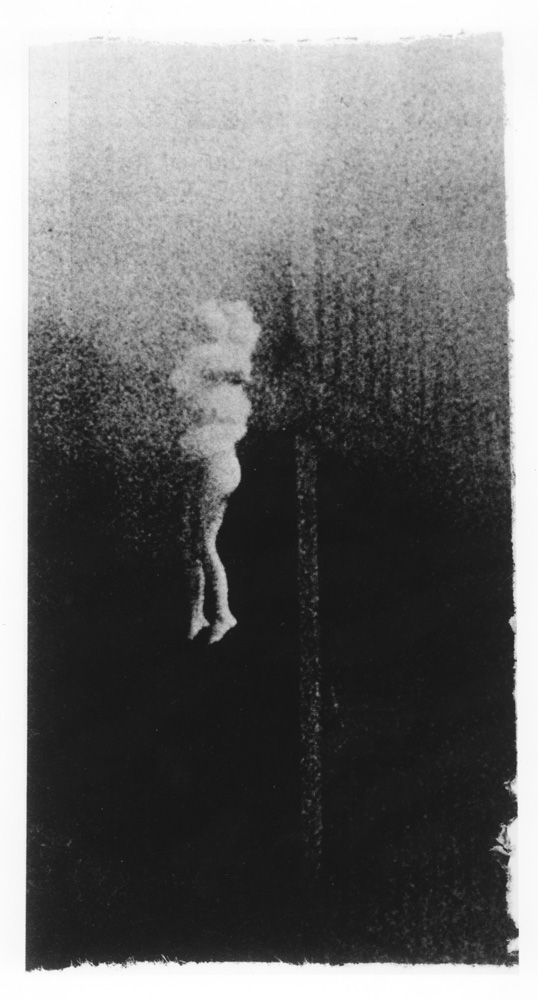

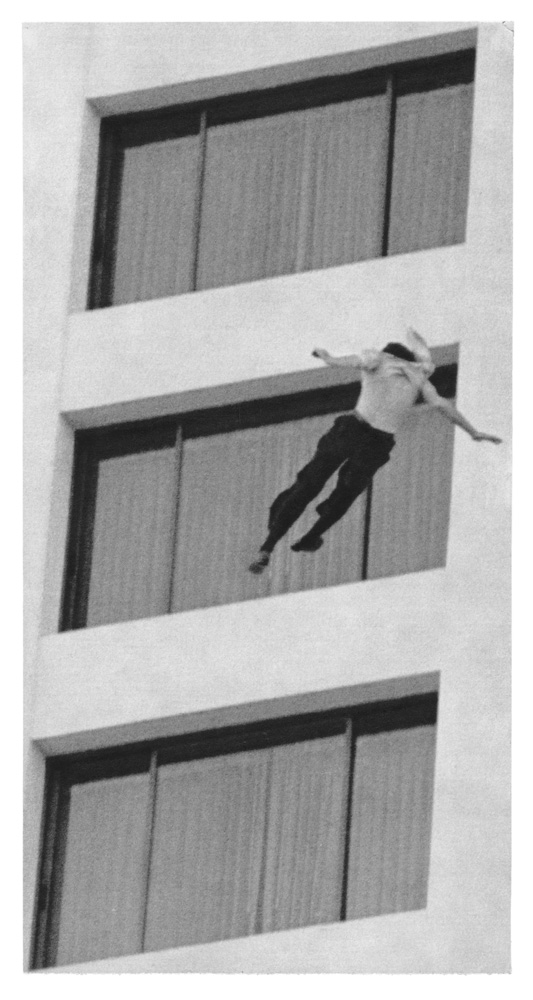

La Chambre Claire, translated as Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, by Roland Barthes, was published in Paris in 1980, the same year that Sarah Charlesworth exhibited her series of large-scale, black-and-white photographs of falling bodies, Stills, at Tony Shafrazi’s Lower East Side gallery/apartment in New York.2 The coincidence marks a transitional history, where the fact of the photograph as an object in the world—a paper thing one might handle and hold, a thing to touch, to place in an album, a folder, or a frame, a thing that might fade or spot or tear—was beginning to erode, eventually to dissolve into something else entirely: a digital image, a thing of light that eludes our grasp. Returning to this conversation, in which the indissoluble connection between photograph and object depicted was rarely questioned, allows that historical moment to resonate, opening up a space for us to consider what was gained and lost, in and on our screens.

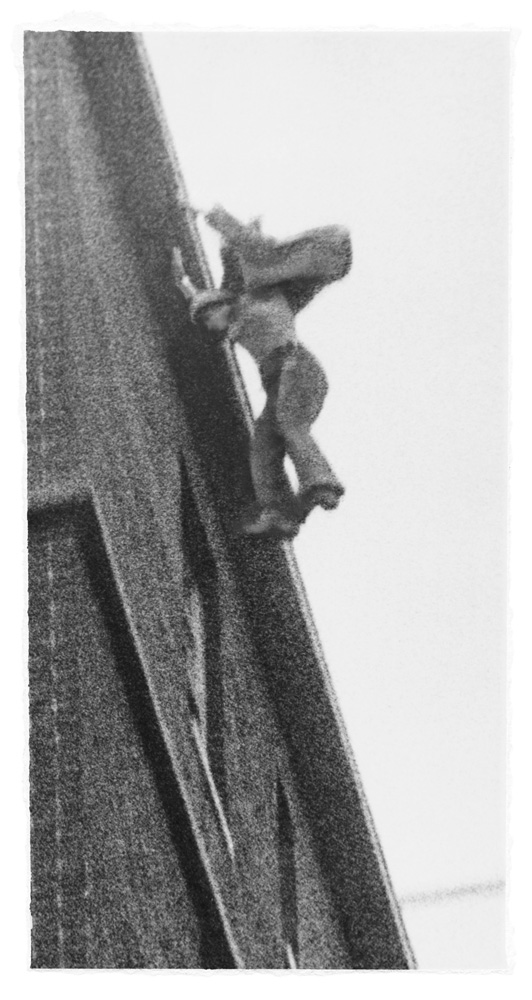

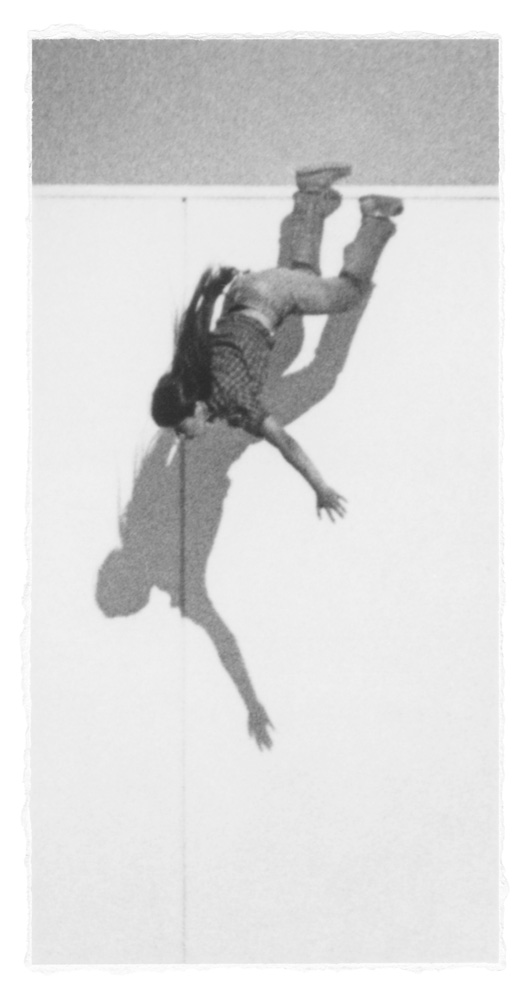

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Woman, Hotel Corona de Aragon, Madrid, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Sarah Charlesworth’s Stills enacts a series of interventions on a set of found photographs, photographs that present moments of dramatic intensity and uncertainty: scenes of people falling. The “referent” here, the thing in the world depicted in the photograph, is a human being in extremis. Perhaps Charlesworth chose these photographs precisely because the referent adheres so extremely. It is almost impossible to enter into a consideration of Photography and its operations while we are transfixed by an image of someone apparently plummeting to a certain death.

Nevertheless, certain elements in the structure and form of the Stills push against these tendencies, insisting on a deeper investigation, not only of photography itself, but also of our unacknowledged wish to sustain the illusion that the photograph is, as Barthes writes, “always invisible.” Charlesworth makes the photograph visible in a number of ways, and in so doing, the work disrupts our responses to those falling bodies. In part, her project is to “unglue” the condemned man and the corpse, in the indelible metaphor that Barthes presented, working to separate, if only momentarily, the depicted scene from the apparatus of depiction. Yet I believe she was interested in these scenes partly because of the resilience of our relation to the falling bodies: no matter how far down the path of analysis we go, the intensity of the image returns, to compel us to look again, to feel something complicated, to experience a state of suspension and uncertainty.

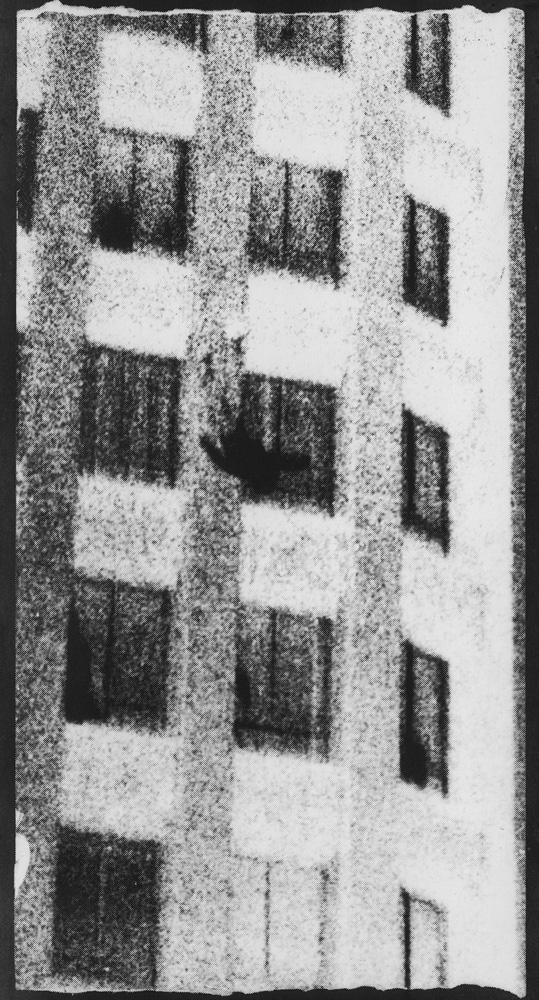

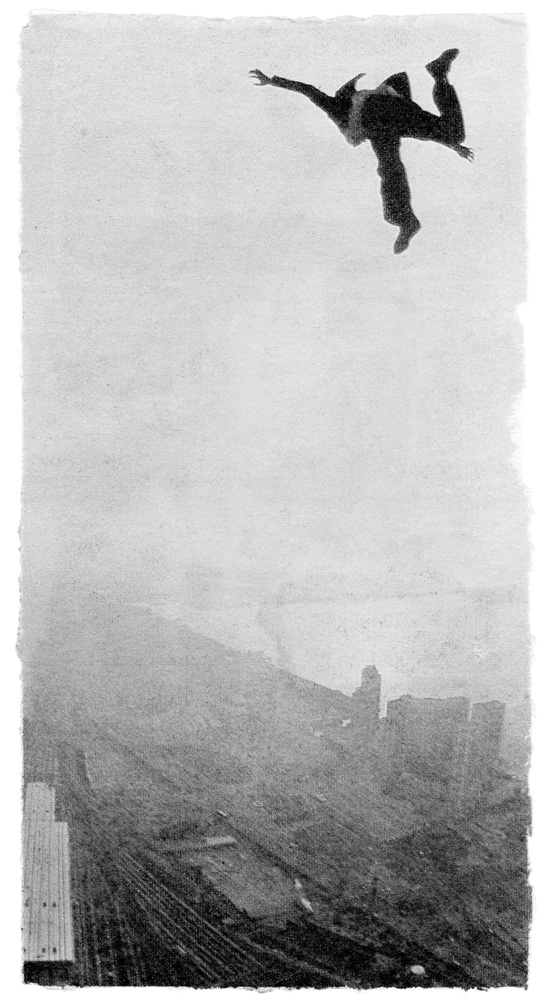

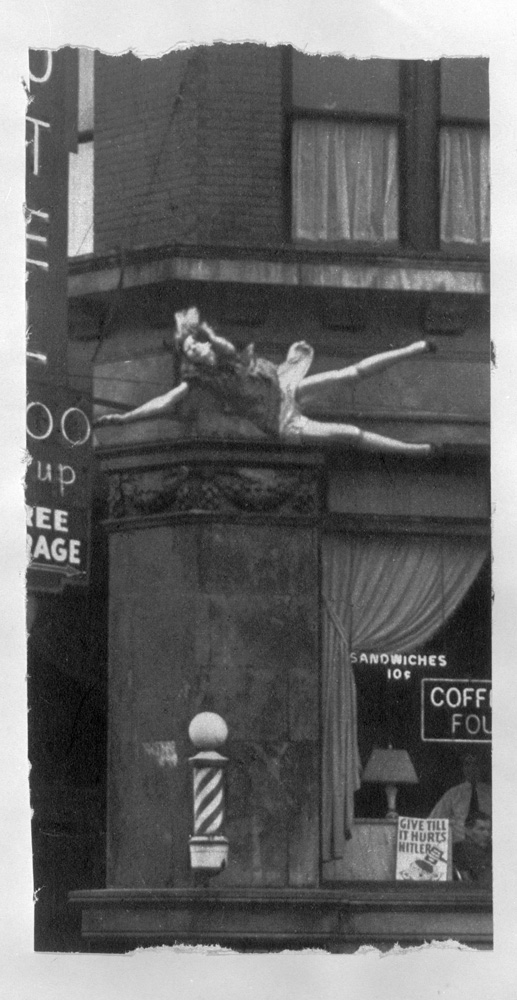

Sarah Charlesworth, Thomas Brooks Simmons, Bunker Hill Towers, Los Angeles, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

A moment, suspended: this is what every photograph presents.3 In Charlesworth’s series of 14 photographs, the moment appears to be suspended between life and death. Bodies fall, and the logic of their falling remains outside the frame, missing from the title. The buildings and structures that provide the occasion for their falling are present, however. (No one is falling from a cliff, a promontory, a waterfall, or a tall tree.) The uncertainty of the possible outcomes of these falls is matched by the uncertainty of the circumstances that precipitated them. We are left with the set of photographs, a space of comparison, in which one illuminates the other. We are left with Charlesworth’s titles, which provide the name of the falling person, when identified, and the location of the fall, when known. The photographs give evidence of an action—in each case, someone falling, their fall suspended in the stasis of the photograph—and by looking carefully at this evidence, a glimmer of something else comes through: a set of propositions regarding the image, life, and death.4

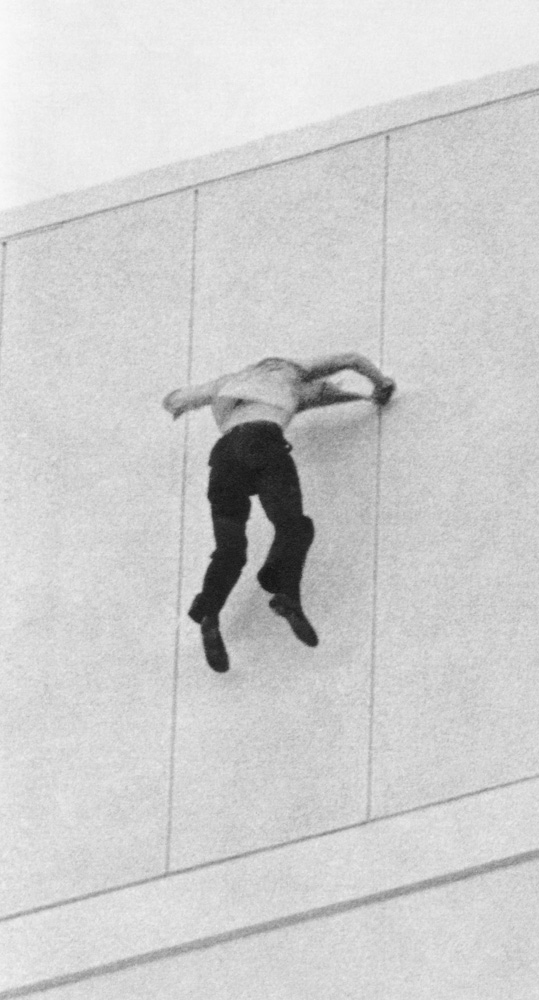

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location (#2), 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Over a period of time in the 1970s, Charlesworth collected more than seventy photographs of people falling; in the original exhibition of Stills, in 1980, seven photographs were presented.5 After the exhibition closed, some were dispersed among different collectors and, as each work was unique, the dispersal was final.6 In 2009, she produced an eighth work, for Musée d’art moderne et d’art contemporain (MAMAC) in Nice, France, using a photograph “pasted up” but not printed in 1980, Unidentified Woman (Vera Atwool, Trinity Towers, Louisville, Ky.). In 2012, Charlesworth made a complete and unique artist’s proof edition, for acquisition by the Art Institute of Chicago. In thinking through the process of reconstructing her work from 1980, Charlesworth recognized that the project had never been completed. Other photographs from her personal archive had been selected in 1980, but considerations of space and financial limitations had prevented her from printing and framing them at that time. In 2012, she printed 14 unique works, titled Stills and dated 1980; she regarded this as a resolution of the project rather than an addition to it. Stills (1980) was exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago from September 2014 to January 2015, and more recently at the New Museum, as part of her retrospective Doubleworld, from June to September 2015. Each work in the series of 14 black-and-white framed photographs is 78 × 42 inches, and all are derived from source images collected before 1980.7

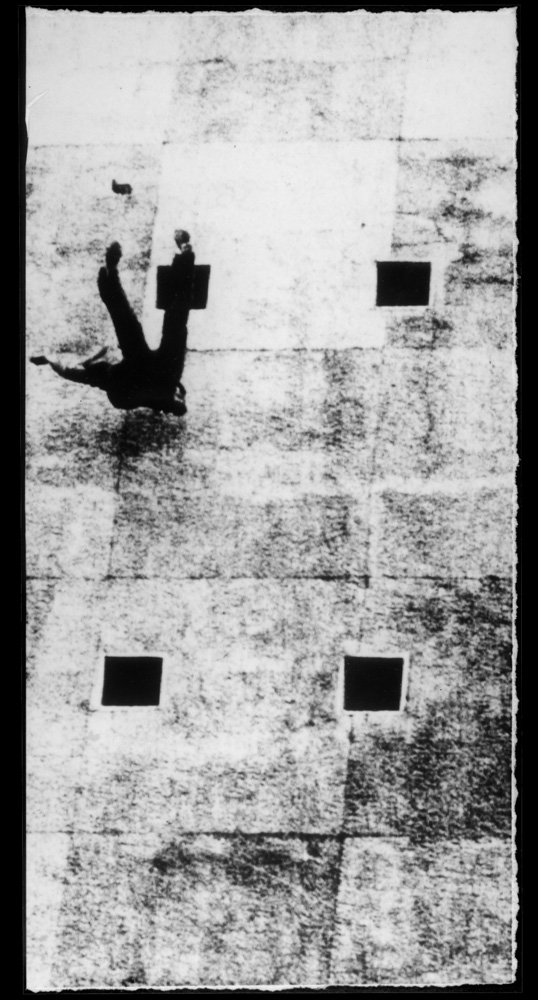

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Ankara, Turkey, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Each photograph presents a photograph of a falling body. At first, that doubling is overlooked, like a typographical error: the work seems merely to be an image, a tremendously powerful and compelling image of a falling body. But certain elements resist this fall into the image, reminding us that we are looking not at a person, falling, but at a photograph of a photograph. The layering and repetition become meaningful, pressing, as questions of mediation and translation emerge.8

The work presents a photograph, and therefore, we imagine, there was once a photographer. We quickly recognize that this hypothetical yet necessary agent does not coincide with the artist.9 This first photographer “caught” a body in motion; was this capture incidental or planned? A falling body might be a suicide, and certainly for me this was the first and most pressing interpretation of the scenes presented; I had to be reminded that there might be other reasons for people to fall from buildings. Despite this uncertainty, the emotional power of the work is in part generated by the apprehension that the image presents a moment just before death. Is it conceivable that someone would arrange to have her suicide leap recorded photographically? More likely this is a press photograph. Like something out of a now ancient mythology of the intrepid reporter (Weegee?), I picture the newshound listening in on the police radio, racing the cops to the scene of the crime, where the suicidal person refuses to be talked down, and the photographer raises the camera just in time to catch the body in flight.

Sarah Charlesworth, Vivienne Revere, New York, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

This scenario seems more plausible and indeed tolerable than the truly terrifying thought of a photographer looking up, by chance, to see and then take the picture of a falling body.10 (As all of these photos were taken before 1980, the familiar fluidity and ease of merely raising one’s phone to capture the scene was out of the question.)

Or is it a different scene entirely? The firefighters have a net, the woman jumps, falling for another purpose: to save her life? The sudden horror of seeing someone falling to her death, or leaping into a net, did not prevent the photographer from taking the picture. It’s a professional photographer, then, someone “on automatic” who has made a decision to postpone ethical considerations until after the critical moment, to consider meaning in the darkroom, rather than on the street.

Yet another kind of photographer is called to mind, the 1970s art photographer—described as “deluded romantic flaneurs with cameras,” operating in a blurry territory between “art” and “documentary.” These artists fetishized Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” and moved through the moving world with eyes wide open for the perfect coincidence of camera and event. In eschewing both explanatory captions and the conventional distribution networks of journalism, they struggled to preserve an idealized version of photography as a way to represent reality.11

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location (#3), 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Another possibility: some of these falling ones are stunt people. It’s a staged fall, then, and while the risk of death may be real (stunt people do die doing stunts), it would be an unintended outcome of the fall. The photographer, in such a case, would be positioned in advance, poised for the leap.12 Our perception of the agency of the people falling shifts with each scenario: a desperate decision, an accident, a display of the stunt person’s skill. Somehow the most distressing version is the thought that the falling body is falling accidentally (leaning out the window, reckless, tipping into a point of no return) only to coincide with a photographer who aimed the camera incidentally and happened upon this sight.

These multiple, imaginary photographers and their motivations belong to the viewer, urgently supplementing the bare fact of a set of pictures of falling bodies. Each photographer remains nameless, though the names of the falling people are given in Charlesworth’s titles, when they could be identified. Of the fourteen works, nine are designated “unidentified man” or “unidentified woman,” and four are simply named. The odd one out is Unidentified Woman (Vera Atwool, Trinity Towers, Louisville, Ky.), as if she had initially been unidentified, then subsequently recognized and named. The location of the fall is also included in the titles of 11 works, though not the date. The remaining three bear the title Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location.

The work opens up a series of unanswered questions: who is falling, and why? The accident of the photograph: a question of speed (bodies fall fast), proximity, the photographer’s readiness. The fact of the architecture in the photograph: this is not a natural fact, but a built environment as a self-chosen weapon. As a small child, my earliest encounter with the idea of suicide came from my grandparents’ albums of old New Yorker cartoons, where jokes from the 1930s about bankers on the window ledges of skyscrapers were abundant. The first actual suicide that pierced my consciousness was Marilyn Monroe’s in 1962. I was seven years old, and I lived in New York, a city of tall buildings. Hearing that she’d killed herself, I imagined her falling from one of those buildings.

In Stills, the dimensions of the fourteen framed prints (six and a half feet tall, three and a half feet wide) produce a roomful of elongated rectangles that open up to a human scale (our bodies fit into that shape, like a coffin or a single bed) at the same time as invoking the façade of a building.13 At the New Museum, the work was tightly hung, and a complex relationship was set up between the depicted bodies in relation to my body, and the depicted architecture in relation to the architectural forms that surrounded me. The falling bodies are never cropped by the edge of the image; they may be blurry or silhouetted, but they are whole. By contrast, the buildings and other built structures in these photographs are always cropped and incomplete, as if connecting invisibly to a continuous, ongoing space and time. That invisible connection extended outward, to the architectural space in which I found myself. In this city, New York, the boundaries of my body are defined in relation to a built environment. Looking at the Stills, the potential violence implicit in the form of a building itself, in the concrete sidewalk, was activated.14

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Corpus Christi, Texas, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Still, we can’t figure out what is happening from looking at these photographs or, indeed, when it happened; we can’t derive a narrative that holds up for more than a moment.15 The photographs point to their titles, which tell us very little. The titles point back to the image, irresistible and indecipherable.16 We recognize that this photograph, like all photographs, is divorced from its context, both spatially and temporally. The boundary of the photograph removes it from the infinite space of the moving world, and the temporal limit of the photograph (each photograph involves speed, timing, duration) removes it from the flow of time. In this work, the arbitrary cut of the edge of the photograph, like the excruciating limit of the timing of the exposure, unfolds into the vast unknowable of everything that is left out.

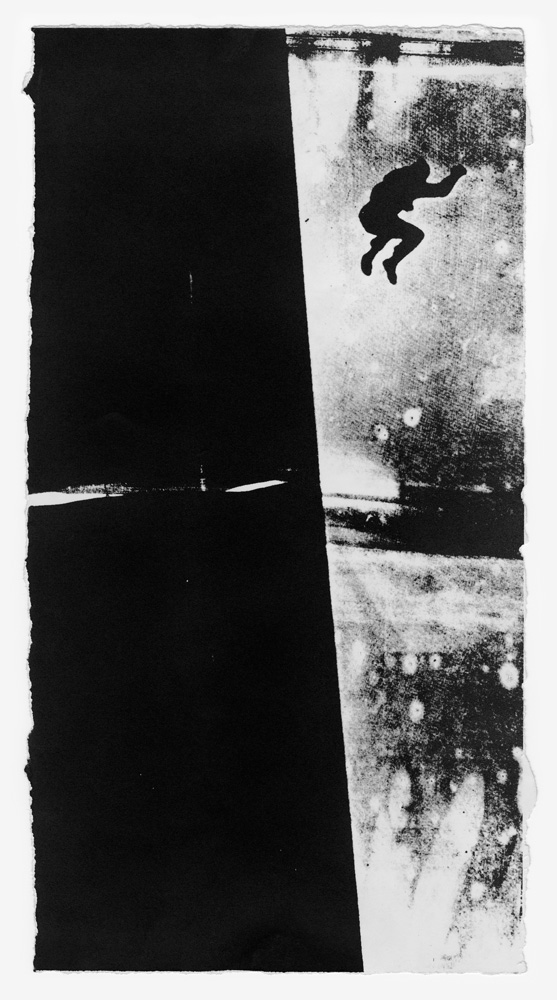

Each of these photographs compels our attention, but one from the set of seven prints exhibited in 1980 stands out for another reason. It was a familiar image, particularly in the context of the New York art world, for the simple reason that it had already been appropriated and incorporated into an artwork by Andy Warhol. Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location is a photograph of a work by Warhol titled Suicide (1962), an early silkscreen that itself used a news photo of someone jumping from a building. It shows a divided field, the rectangle bisected by the edge of a building, the body silhouetted against a bubbling, mottled sky. Charlesworth did not seek out the original news photo; instead she rephotographed the Warhol silkscreen from an art book and redeployed it to make her own artwork.17

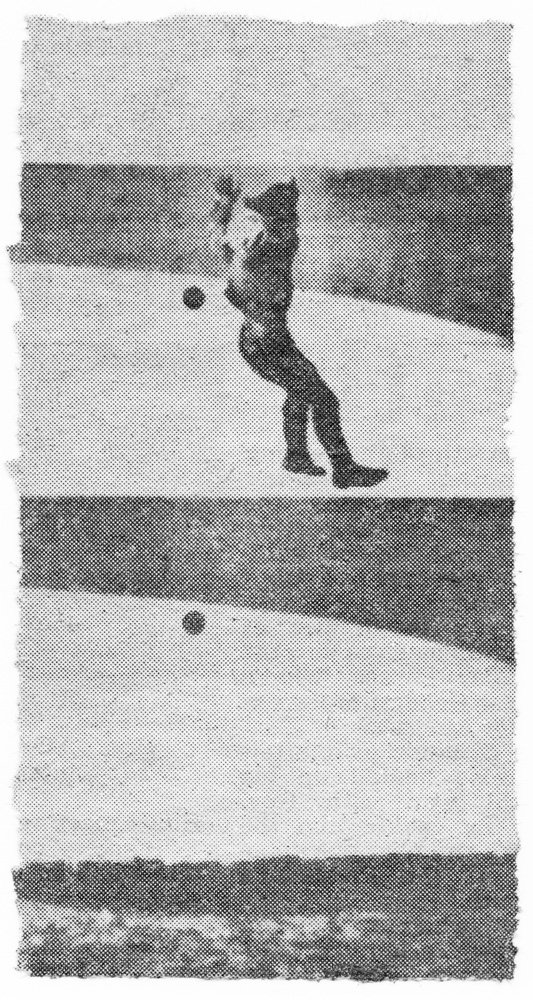

,strong>Sarah Charlesworth, Dar Robinson, Toronto, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

By including the Warhol, Charlesworth radically intensified the intervention of appropriation. For an artist to reach into the image archives, to select and shape and represent an already existing photograph, is still to reserve an authority and originality for the artist in that selection and shaping. When the image set Charlesworth dips into emphatically includes a well-known work by another living artist, who himself almost twenty years before reached into the image archive to select and shape and re-present, she sets up a mise en abyme of reproduction. This strategy of echoing repetition works to undo the remaining aura associated with the appropriator’s act of selection—to undermine the hierarchy that validates that artistic act of selection and re-presentation, which always involves moving something out of context and creating a temporary yet resilient boundary around it. Already in 1980, when these strategies were just beginning to emerge in New York, Charlesworth’s double appropriation (appropriating an already appropriated image) pushed questions of value to the limit.18

Rephotographing the Warhol reenacted Warhol’s original procedure of collecting a news photo, enlarging it, and transposing it from the print medium, held in one’s hands, to a larger scale (40 x 30 inches) on the wall. Charlesworth enlarged it further and changed the proportions of the image: her format of 78 x 42 inches crops the Warhol image, reframing it to emphasize the tilt of the building, a tilt that makes evident the angle of the camera that captured this leap. Warhol made multiple screen prints using this image: they show the windows of the building, distorted perspectivally, as if the building itself is aghast and leaning away from the sight of the suicide. In Charlesworth’s version, the copy of a copy, the building’s windows disappear: detail and definition are eroded, becoming a shadow.

Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location is a half-joke—it’s a Warhol, all too easy to identify! Its inclusion in the set of Stills begins a process of unraveling the emotional intensity of the images, raising questions about the artist’s authenticity, as well as our own. It was a joke that many people didn’t get, it seems, as if the critics were unable to follow the critical clues and cues that pointed viewers toward the pleasures of what Laura Mulvey called “passionate detachment.”19

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Along with her deployment of the Warhol, Charlesworth used a number of other devices to disrupt the flow of emotional engagement and raise our awareness of the nuances of selection, enlargement, and framing. The most obvious move is one of displacement: these photographs derive from pictures cut out of newspapers and magazines. The usual “scene of viewing” would be in the context of a mass-produced newspaper or a magazine, like Life, which was an inexpensive and ubiquitous weekly publication that contained multiple photographic essays as well as individual photographs. 20 We are invited to imagine the artist spending time in the image libraries, leafing through publications or poring over open drawers of metal filing cabinets full of 8 x 10 inch black-and-white glossies, and purchasing copies of these press photos, or duplicate copies of a specific edition of a newspaper or magazine. Another kind of time is woven into the work, the time of researching and collecting and archiving the images, folded into the historical elsewhere that the photographs record.

To transpose the image from the print mass medium to the gallery wall is a move that is so ordinary now as to be almost imperceptible. Yet it reconfigures our embodied relation to the image: we look at it in a different way, as the scale and the vertical orientation together refocus our attention, and the power of the photograph to immobilize and fascinate is released.21 Enlargement is a key part of this move from publication to wall: traces of the original dimensions and image quality are evident in the texture and grain of the blown-up photos. In some cases, the perceptible halftone dots emphasize the sources of these photos in newsprint or magazines. The different materialities of their surfaces point to the scale of their original printing, as well as to the type of film and the exposure of the original photograph. Where the halftone dots are evident, it’s clear the printed source image was quite small, and both the often-overlooked miniaturization of the news photo and the hyperbolic blow up of the artwork become visible.

Crucially, the scale of these photographs connects the viewer’s body to the image substrate, as opposed to the falling body itself. One element of the viewer’s embodied experience when seeing these works in real life is, in a sense, to become (in imagination) a kind of conduit or bridge between the falling body and the actual architecture of the space in which we stand. This spatial phenomenon works against identification as such, to produce another kind of relationship to the pictured event.22 Sometimes it is described as entering or stepping into the photographic space.23 It could be described otherwise: the potential of falling enters the shared architectural space of viewing, shifting our embodied relation to it.

Sarah Charlesworth, Patricia Cawlings, Los Angeles, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

In addition to the question of scale, another intervention demands interpretation: the tear of the edge of the photograph. (Of the 14 images, 12 have visibly torn edges.) This tear exposes the paper fibers of the printed photo, and the roughness of the tear provides further evidence as to the scale of the source photograph Charlesworth was working with. At first glance, one might mistake these tears for a deckle edge, as if the enlarged photographic images were printed on some kind of handmade paper, and then mounted on a mat (white or black) and framed. A closer look reveals that each work has an embossed seal on the lower right corner, which is placed partly on the image and partly on the white or black background. The circular studio seal, three inches in diameter, reads: “Sarah Charlesworth New York.” It is not inked, and is only perceptible through the raised surface of the circle and letters.24 However, this seal performs a crucial function by verifying the continuity of the surface of the image and its support, insisting that this is not a picture mounted on mat board, but on the contrary, the entire work (image and background) is one photograph.25

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Woman, Genessee Hotel, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

The embossed seal shows that the work consists of a photograph of the torn edge, rather than a photo printed on paper with a torn edge. And the tear points us toward the cutting, the missing context of a specific newspaper or magazine where the photograph might be found, as well as the cropping within the image that took place.

Further, this cropping within the image is mirrored in the temporal dimension of the fall: each photograph in Stills presents a body stilled, in the middle of the act of falling. The photograph’s edges point to the event as without beginning or end, in medias res, cut out of the surrounding space and time, but the moment depicted is also, so to speak, cropped out of the event itself, which is always in the middle, indeterminate, and never concludes.26

The torn edge offers us more: it evokes a paper object, a thing in the world, and the substance, texture, and weight of that paper thing can be sensed in the tactile qualities of the tear itself. Considering the tear, we experience the Stills as objects, paper things in the world, and we witness their transition, as these traces of Charlesworth’s own cutting and cropping merge into the new photograph, dissolving into a smoothly continuous surface, itself marked by the embossing stamp. The interruption of the embossed mark, like the visual traces of the tear, prove the ontological status of the image as an object with weight and heft, a thing you can hold and touch and cut into: a thing that the artist held and touched and cut.27

Sarah Charlesworth, Jerry Hollins, Chicago Federal Courthouse, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

It becomes clear that a series of cuts and transpositions lies within the work. The original scene (what used to be called the “pro-filmic event”) was framed in the camera by the photographer, who then developed the film. In making the original print, the photographer most likely adjusted the framing of the negative, allowing a greater proximity to the scene, or a different composition of the relation of the falling body to the building or the street. The photo was distributed and later the print newspaper or magazine that purchased the photograph may have reframed the image once more, to emphasize its dramatic or informational aspects.

Charlesworth collected such images from various sources: newspapers, the New York Public Library, press photo archives. She determined what part of the original print (or its newsprint version) interested her, she determined the proportions of the final work, and she then cut or tore the photograph, reframing the scene, using a ruler to steady her hand. (Alternatively, it’s possible that occasionally she rephotographed the press photo, and then tore her own photograph, making yet another cut into the field of vision that the image purports to open out to the viewer.)28

She glued the torn paper photo onto a mat board (white or black) to create the “paste up,” and this camera-ready artwork was taken to a commercial “repro house,” where an 8 x 10 inch negative was shot. This was taken to a photo lab, where a gelatin silver print was produced, to a scale of 78 × 42 inches. The final print was then marked with the embossed studio seal and framed in a narrow black frame.29

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Woman (Vera Atwool, Trinity Towers, Louisville, KY), 1980. Black-and- white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

In 2011 and 2012, when Charlesworth was producing the artist’s proof of Stills for the Art Institute of Chicago, she was concerned to complete the project as she would have done in 1980, without altering her intention and without the perspective of all the years of working and thinking that had ensued. As a result, she found herself in the strange predicament of being obliged to reenact a tear. Each of the photographs had been selected before 1980; some had been pasted up and, in some instances, she had to re-tear the edges, in order to adjust the proportions of the image. She described it as wanting to make these tears as she would have done in 1980, over thirty years before. In a sense, she had to time-travel back into her own body, her 1980 body, a body that went out dancing at the Mudd Club, a body that didn’t yet know what would happen next.30

There’s a bodily gesture registered in these tears, the tears from 1980 and the tears from 2012: a single, sudden move, like a slap or a leap, with its own distinct sound.31 Does the embodied quality of the tear return us to those falling bodies? Does the singular instance of the physical tear deconstruct the relay of mechanical and technological mediations and framings that accumulate almost imperceptibly between the event and the viewer of Stills?

I would argue that part of the power of the spectacle resides in its capacity to both show and conceal the event, to recontextualize it in ways that replace and displace its meanings. Within the spectacle, the event is apparently brought close and simultaneously held at a distance, through the structural mediation of a series of representational technologies.

We may look at a picture in a magazine and remain comfortably unaware that, somewhere behind and within the magazine’s presentation, lie the camera, the various technological devices for developing and printing the photograph, the Associated Press wire service that distributed the image, and the editors, designers, and layout artists—not to mention the paper mills, the printing presses that manufactured the magazines, the trucks that delivered them to the newsstand. At each translation of the image, human interventions took place, reflecting different value systems regarding scale, positioning on the printed page, and context. In the gallery, we are held by the image, almost unaware of this technological relay and the various sites where the image was re-framed, put to work, and divorced from the event and its context, in a series of apparently seamless transformations.

The singularity of the torn edge functions as a punctum, to use Barthes’s term.32 The tear interrupts the echoing relay of the spectacle, to return us to a body, a gesture, a single moment. The tear is indexical, bearing traces of a singular action, analogous to the photograph itself, which functions as a material residue of the event. It would be easy to speculate that these torn traces of her embodied gesture constitute a form of resistance to the technological spectacle, yet Charlesworth chose not to present the torn photo itself. Instead she rephotographed it, calling into question any idealism that might propose the immediate body as simply working to unravel the spectacle. Her work breaks the photograph open, as the living being who made that specific, inimitable tear in the fabric of the paper literally forces her way into the image, invoking the reality of the fall. And at the same time the image closes up again, erasing her, to propose a distance and an interruption, to make a space of detachment.

On some level, Stills enacts an interrogation of the terms of a mass media that regularly presents such images as a form of commercial entertainment. The technological spectacle dehumanizes the people who jumped, fell, or leaped into the void. I would argue that the torn edge of the picture demonstrates the reality that photographs are cut out of their contexts, even as they cut whatever they show or depict out of their contexts. (In other words, photographs decontextualize and they are continually decontextualized.) The gesture appears to be a strategy for undoing the spectacle, if that were possible, using the sudden tear to bring us back to a specific body, a human being, in free fall. At the same time, in photographing the torn edge and presenting that photograph, Charlesworth re-performs the very operation of that spectacle, building the relay of reframing and rephotography into the fundamental structure of the work.

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Ontani Hotel, Los Angeles, 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

These images are uncertain: in many of the photographs, the body is blurred, the features unclear, the locations imprecise, the motivation for the fall always out of reach. It would be ludicrous to suggest that the viewer can in any sense share the different experiences of these individuals falling. Despite that fact, we identify with them. And through that identification, paradoxically, the images return us to an ontological fact of our own uncertain being, suspended as we are between life and death.

It goes without saying that our relationship to technology and images has changed since 1980. Our multiple screens allow access to apparently unlimited images, and within our digital applications, we can do whatever we like with them. These pictures flow seamlessly, held in suspension by the smooth and shiny surfaces of our screens. The illusion of control is endlessly rehearsed in our swipes and pinches; there’s a kind of horizontal access to simply everything, as if the impulse to hold something in our hands, to dig into a physical archive, or to store paper photographs in a filing cabinet, is both archaic and anachronistic. Still, we cannot make a tear in the Internet.33

In her essay “In Defense of the Poor Image,” Hito Steyerl reminded us that digital photographs are in fact material things, and the apparent mobility, instantaneity, and immateriality of the digital realm are illusory.34 Our websites rely on gigantic air-conditioned warehouses full of servers; every time a digital photo is compressed and decompressed, visual information is distorted or lost. Disks degrade; glitches proliferate. It turns out that paper may be the best way to preserve photographs and other information: that same paper that can fade, spot, or tear.35

In Camera Lucida, Barthes spends time with Alexander Gardner’s 1865 Portrait of Lewis Payne, a young man who is about to be executed. He writes of this photograph: “I read at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake… In front of the photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die: I shudder, like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.”36

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location (detail), 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 x 42 inches. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

Sarah Charlesworth’s Stills dives into the moment of catastrophe itself, enacting the paradox that, in preserving the final moments of life, the photograph can only point towards death. Like a still life, a nature morte, the photographic image speaks of loss, time passing, and the ephemeral being. Few human experiences are as brief and intense as a fall from a building: we imagine an incommunicable intensification of the sensation of being alive that comes when risking or seeking death. These photographs of falling bodies connect the existential foundations of being in the world to the apparatus of the photograph: indexical, immediate, and uncertain. At the same time, Charlesworth’s work insists that without the surrounding context of the moving world, the photograph cannot tell us the rest of the story. One might be persuaded that what it can speak of is the most important stuff: that everything passes, and it’s all over in a second. On the other hand, the fascination and pleasure we find in the spectacle of the suffering of another is something we (and the tabloids and reality TV) take for granted, to the point where that fact, too, becomes almost imperceptible.

Charlesworth’s demonstration of the workings of the photographic apparatus brings us to an ethical point where we can only question our motivations, our identifications, and our delights. Through the tear in the photograph, we identify with the gesture of the artist, sensing the resistance and give of the paper, the unique form of its edge, which itself points to the singular gesture of the fall, the click, and the tear between life and death.

Artworks are the site of an intersection of agency and chance. In every instance, the artist’s intention encounters the materiality of her medium (language, paint, a news photograph) and, in that material encounter, her idea is translated and transformed. Looking at Stills, the idea of agency is always in play: how much of what we are looking at is an accident? Charlesworth’s formal structures have a conceptual clarity that tightly contains the uncertainty of the image. Nevertheless there is always an element that resists interpretation, marking the limit of meaning. The tear through the paper photograph makes a new edge, a limit, and that tear is deliberate and decisive. Yet, in its invocation of the artist’s embodied gesture, in its manifestation of the unpredictable materiality of the torn paper, the element of chance, of something outside our control, is revealed.

The tear, like the fall, is a unique event, cutting through the image to bring us to a momentary glimpse of the real. Our contemporary historical predicament idealizes the endless images on the glowing screen, their slippery mobility, their apparent immateriality. They seem to cheat death, decay, and all the other problems that belong to the vulnerable object, or the body. Sarah Charlesworth’s Stills invites us to consider the task of finding ways to cut into and through these slippery surfaces, tearing them open, excavating and revealing the rough fibers that constitute us, and the image, as things in the world.

Leslie Dick is a writer who lives in Los Angeles.