Featuring Catherine Chalmers, Beatriz da Costa, John Divola, Sean Dockray, Sam Easterson, Carlee Fernandez, Jill Greenberg, Fritz Haeg, Kathy High, Desirée Holman, Natalie Jeremijenko, Lisa Jevbratt, Nina Katchadourian, Hilja Keading, Rachel Mayeri, M.A. Peers, Nicolas Primat & Patrick Munck, Alison Ruttan, Corinna Schnitt, and Jim Trainor

The Revolutionary Promise

They were here before us—the animals— and we were once them. […] They know we are different and their eyes tell us to keep our promise.

–Geoffrey Lehmann1

When I heard that Intelligent Design: Interspecies Art featured international artists collaborating with animals, I was eager for the revolution. With this salvo “Intelligent Design will be the first exhibition in the U.S. to explore interspecies art,” curators Tyler Stallings and Rachel Mayeri prime us for a barrage of artists teaming up with a wide range of animals, from cockroaches to trout, as a way for art to challenge anthropocentrism. The exhibition includes thoughtful pieces in which humans gave up some authorship, where animals had agency, thus contributing to the meaning and sense of the work. But Interspecies Art, with its lack of guiding framework and its diffuse selection of work, does not rally strongly for the necessity of animal-human collaboration today. Much less did the artists’ largely Californian provenance, including several UC faculty members, support the exhibition’s claim to being international. If the exhibition leaves a lot unfulfilled, individual artworks raise compelling questions about our contemporary desire for an alliance with animals and the elusiveness of meaningful artistic collaboration.

Although René Descartes’s valorization of humans embedded in his Je pense donc je suis finds his sympathizers in Georges Bataille and Martin Heidegger,2 it is more common in the academy these days to combat the anthropocentric world-view, which we blame for many social and ecological ills facing us. If earlier the difference between animal and human helped to define ourselves as human, now the exclusion of the animal—on the basis of that same difference—has impoverished and dehumanized us.3 To reverse that, animal-centered discourses are proliferating.4 Humanism or post-humanism, depending on whom you listen to, is pitted against anthropocentrism and its playmates anthropomorphism and zoomorphism. Mercifully, artists are not so hung up on academic questions about the correctness of a scientific or post-humanistic approach to animals.

Upon entering the Sweeney exhibition space, down the main hall one sees a buffalo head paired with a portrait of a bear. On the left are dog pictures. Swing right for a row of tiny photographs of animals and a room with multiple video works, all with animals, from the humble ant to a placid cow. What’s missing is the animal we call human. Or is it?

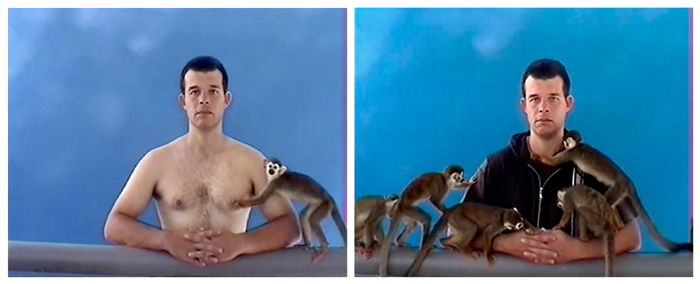

Nicolas Primat with Patrick Munck, stills from Portrait de Famille (Family Portrait), 2004. DVD, single-channel, 2 mins. Courtesy of Patrick Munck.

Interspecies Art becomes more interesting when we think about how and why we, animals as we are, think with animals. In the absence of the animal’s active contribution in many of the works, this is the only sense in which one can justly claim the artists to be collaborating with animals. A sensitive recalibration would recognize that the human point of view compulsively and inescapably permeates any viewing, conjuring, or reading of the animal, whether real, representational, symbolic, or rhetorical.

Catherine Chalmers, still from Safari, 2007. DVD, single-channel, 7:18 mins. Courtesy of the artist.

The Art in Ethnography and Ethology

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.

–Ludwig Wittgenstein5

If we could talk to the animals, just imagine it

Chatting to a chimp in chimpanzee […]

If we could walk with the animals, talk with the animals,

Grunt and squeak and squawk with the animals,

And they could squeak and squawk and speak and talk to us.

–Doctor Dolittle6

The two formulations quoted above create a tension between reality and desire, between the reasonableness of philosophy or science and the aspirations of art. Interspecies Art works both sides of the communication gap. Artworks shed light on these questions: Have we expanded our conceptions of art to the point of making animals true collaborators? Do they squeak and squawk and speak and talk with us? Animals have now joined children and primitives as subjects of the avant-garde artist’s cynosure. All present what philosophers call the problem of the other mind. An anthropologist’s solution is participant observation, whereby one immerses oneself in the lives of the people under study. How do artists answer the experience of otherness and the desire for belonging?

Nicolas Primat took the participant- observer model to heart; he spent long periods of time with a tribe of squirrel monkeys in order to gain acceptance before filming Portrait de Famille (Family Portrait) (2004). This video instantly refreshes the genre of the family portrait and bonds the pictured Primat to the squirrel monkeys as family. Traditional hierarchy affords the eldest and most respected member centrality, with children arrayed around parental figures. But don’t primates come before us in evolution, not after? Or are we the grown-ups to the child-like primitives? Ideas of the representation of self, inherent in the genre of portrait, proliferate with such questions. In contrast to the importunate scamperings and proddings of the spider monkeys—who are considerably smaller, more active, and more curious about him than he seems to be about them—Primat sticks to his pose as the impervious head of family, frontal, unsmiling, and still. The monkeys, of course, don’t and won’t. In the end neither can he maintain the convention—he sneezes and then laughs at his slip up. His animality shows through in the end. From the opening moment, when the monkeys first turn their curiosity to the video camera, we are aware that Primat’s act of curiosity is reciprocal, thus cleverly and humorously questioning the assumption that there is no true partnership between a researcher and his subject. It is a lovely and expanded idea of family and portraiture enabled by two short minutes of videotape.

Anthropology and ethnography, which offered a model of participation for Primat, often demand a narrative of objective analysis.7 Ethnographers immerse themselves to learn and to gain trust, to obtain an insider’s point of view, but they also remain detached, thus objectifying the “object.” Retooling this subject-constructed objectivity, Rachel Mayeri translates primate social dramas for human audiences in a series of videos collectively labeled Primate Cinema. Indeed, Wittgenstein’s above-referenced concern is a problem for which anthropomorphism is both “the symptom and the attempted remedy.”8 In Baboons as Friends (2007), a clip of seemingly ordinary baboon interaction is paired with a reenactment of the same as a barroom scene involving a single woman with multiple male suitors. The latter is shot in black and white, film-noir style, perhaps to emphasize the tense animal drives underlying both clips. A rather uninflected voiceover relates monkey behavior to its staged human correlates, or is it vice versa? The anthropomorphic metaphor has been cleverly reversed. By flagrantly and humorously dodging the risk of anthropomorphic projection, while constructing sentimental fantasies of cross-species identification, Mayeri fulfills the cultural historian Clifford Geertz’s contention that ethnographies are as much or more about their authors as they are about cultural subjects.9 Primat and Mayeri’s works cause us to wonder, what if we were a “continuous species?”10 They invite us to recognize that self or family is a social and historically contingent identity.

Elsewhere, this impulse to identify with the Other—the animal, the creature—draws a straight if thorny path from anthropomorphism to zoomorphism. We are tempted to seek identification with the animal for all manner of reasons: ritual, aesthetic, psychological, sexual, escapist, or political.11 In Interspecies Art, the works that tried to embody the animal, by performing the physical posture and movements of the animal under consideration, were prickly in their directness of method and message in embracing zoomorphism. As a side-show to his Animal Estates (2008), Fritz Haeg engaged a largely unclothed male model to assume the poses of a dozen local animals, as choreographed by a dozen dancers, and turned them into postcards, which are displayed here as artworks.12 Without recourse to text there are few obvious ways to identify the animal being depicted and surely we are free to imagine anything or nothing at all. The postcards and the associated dance call to mind the problem introduced in a seminal paper titled, “What is it like to be a bat?,”13 which argues there is something that it is like to be a bat, but which is inaccessible to us scientifically in absence of being a bat. An attractive response to the problem is the deeply empathetic and affective approach of Elizabeth Costello, a character in J.M. Coetzee’s Tanner lectures. Costello asks, “If we are capable of thinking our own death, why on earth should we not be capable of thinking our way into the life of a bat?” She next declares, “There are no bounds to the sympathetic imagination.”14 It was difficult to see the sympathetic imagination at work in Haeg’s stagings. Instead of being a positive act of understanding, his reads as one that serves to render the animal further “inscrutable and invisible.”15 Similarly,Alison Ruttan’s dual-monitor piece Impersonator (2005) depicts an underwear-clad young human mimicking (on one screen) a cat’s simultaneous pauses and prowlings (on the facing screen) in a spare space more evocative of scientific neutrality than contextualizing habitat. The title, much like the video itself, draws attention to the person assuming a persona. The cat remains forgotten in favor of the cat-like. Our hubris and inability in “becoming-cat,” in attempting an imitation, are doubly magnified.

If these two works faintly bring to mind children pretending to be animals or Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of movement as a form of self-education or performed science, Desirée Holman’s music video, replete with loud visual effects and artless choreography, presents humans playing at “monkeyface.” Troglodytes (2005) records the actions of a troupe of humans in stagey chimpanzee suits who dance in front of a freeze-framed waterfall, smoke cigarettes, and make love in a park. In this scene of touchingly wishful fantasy, the animals are just like us. Too bad the monkeys can’t protest. In these works, animalizing the human has never looked so problematic.16 Merely imitating prevents a real transformation from taking place and at best these works provide an inscrutable translation of pre-existing models of thinking and being.17 It is left to our imagination to what extent the participants in these artworks achieve the feeling and experience of “being there,” as Clifford Geertz puts it.18 If zoomorphism is unavoidable and positively desirable, as Costello would have it, I wish we were better practitioners of it. Would that we rose to Nagel’s challenge with keener efforts.

Oculocentrism

[A] line of sight can just as easily slice through the separation between subject and object as it can define it.

–Bill Viola19

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.

–Marcel Proust20

Thomas Nagel’s query, “What is it like to be a bat?” challenges cognitive ethology. In response the method of hetero-phenomenology is used to make substantial progress towards giving us insight into animal behavior, even if we cannot hope for perfect, total description. In their works, Sam Easterson and Catherine Chalmers undertook to see the world from an animal’s point of view. While Easterson mounted custom-made cameras on various animals and largely let them record until they fell off, Chalmers inserted a macroscopic lens into an insect-sized world, to offer a generic cockroach’s viewpoint.21 These two artists have devoted considerable energy and thought to work that involves animals, and I want to linger narrowly on the operation of their scopic effects.

Easterson’s Animal Cams series (1998-2006) show us the point of view of a whole range of animals, such as an Armadillo Running in Desert or a Sheep Trying to Join Flock, but the works exchange depth for breadth. Although each activates our view of the environment with the unexpected swerves, twitches, and slithers of the animals, the brevity of each catalogued activity and its presentation on a 21-inch monitor prevent both understanding of an individual animal and an immersive experience of its environment. Frustratingly short narrative length does not aid the artist’s stated ambition that “If you’re able to see from the perspective of these animals, you’re far less likely to harm them or their habitats.”22 The commitment to capturing in-depth the experience of each animal was sacrificed in favor of variety. It remains to wonder how the cine-eye23—which aligns, however unevenly, our gaze with the animal’s—assists us in becoming-animal.24 Does looking through rather than into an animal’s eyes transform the conditions of our relationship in a shared world?

In Chalmer’s video Safari (2007), a humble cockroach embarks on its journey, swimming away from our camera to another shore, which offers it a jaunt through a spectacular microcosm filled with delicate plants and colorful exotic creatures, so different from the roach and us. Usually a hunter on safari brings home his trophy-head; here ironically the cockroach meets her “natural” fate—to become a meal for a frog in the “wild.” Instead of collecting naturalia and stuffed specimens as for a Wunderkammer, Chalmers collected live plants and animals to create this fantasy miniscape, her object of wonder. Like the Animal Cams, Safari also aims for a kind of breadth—the marvels of Wunderkammern and the delicacy of the contents of a jewelry box. We never learn the names of the flora and fauna of this improvised realm: it has been set up not for science, nor for the honor of any species, but for pure delectation. All concerns are subordinate to visual pleasure, paradoxically the attraction and the difficulty of the piece. Safari unselfconsciously takes one back to an era of adventure and discovery that preceded classifying and colonizing.25 We are suddenly blessed with innocent pre-Baconian26 eyes and placed in a parallel moment when, as cultural historian Celeste Olalquiaga writes,

[T]he West perceived the world as an object of contemplation and spectatorial delight. …For what distinguishes the age of wonder is precisely that naturalia shifted from being vital elements of an everyday life imbued with spirituality to becoming isolated and commodified as objects and compulsively collected in a “colonization of wonder.”27

In the “Age of Wonder” quartet that is Safari, Chalmers collects; the camera records; the cockroach gazes; and the microcosmic denizens unwittingly participate. Olalquiaga makes very pertinent observations about the Wunderkammern that apply nicely to Safari’s optical emphasis and the resulting fusion of fantasy and reality:

As such, they confirm looking as the fore-most mode of intellectual apprehension and retention, …formally establishing the eye as that “organ of marvelousness” …It is the “ocularis imaginationis,” the eye of the imagination, that is at work here, impassive to anything that does not immediately attract it, dilating its pupils and sending emergency messages to the brain and heart. Encyclopedic collections live for this moment, blissfully ignoring the difference between fantasy and reality…28

Both Safari and Animal Cams are encyclopedic collections of this order and hence are necessarily incomplete. Our examination of them cannot justly reveal what and how a cockroach or an armadillo visualizes and processes an optical experience. In both projects, oculocentrism maps human over animal optics, as if we could share in experiencing their environment through a conflated optical apparatus.

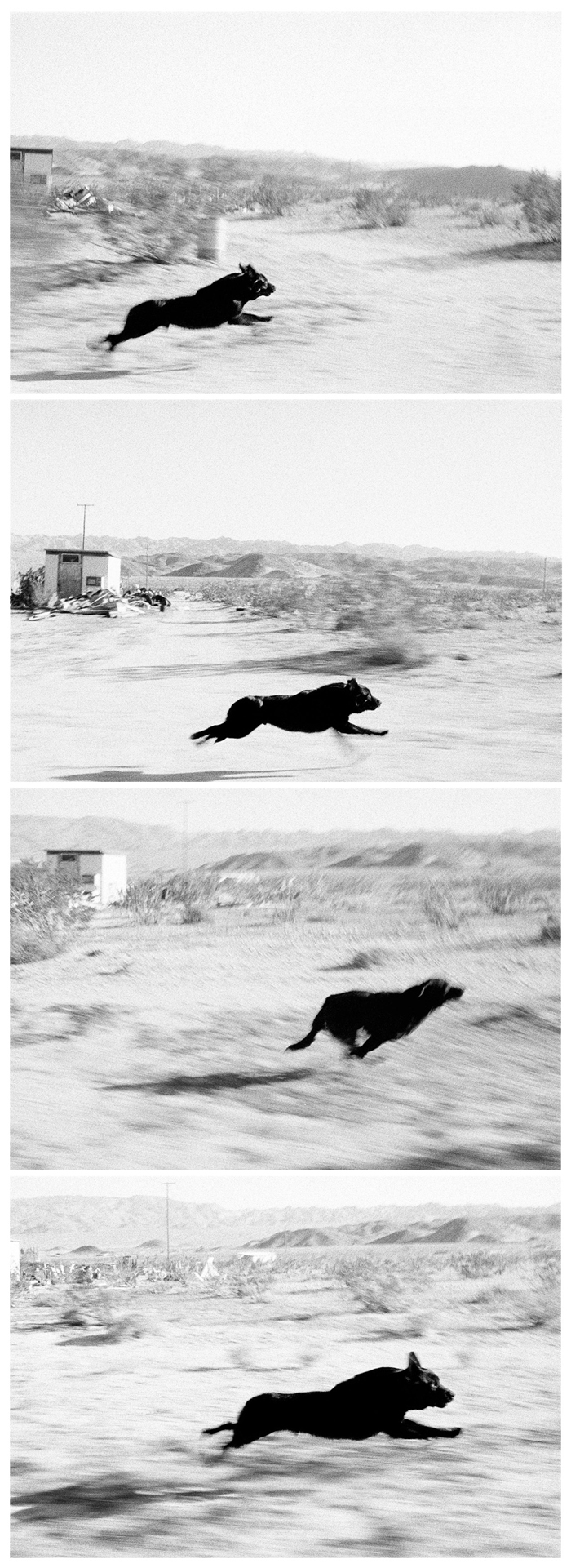

John Divola, images from Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert, D29 Run Sequence, 1996-2001. Ultrachrome pigment on ultrasmooth fine art paper. Four images, 36 x 52 inches each. Courtesy of the artist.

John Divola’s photographic series Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert, D29 Run Sequence (1996-2001) underlines the limits of sharedness; one can share the environment without sharing an understanding of mind. In grainy black and white photographs, both the dog and the desert landscape around it are a-twirl in motion: Divola took the pictures while driving alongside a dog giving full chase. A series of actions and reactions are condensed: in the economy of looking, the dog’s unbounded but bounding curiosity is immediately returned. The ethogram, of a sportive moment, is made together in perplexed animal consciousness.29

Hilja Keading, The Bonkers Devotional (Installation view), 2007. Multi-channel video installation; 13:00 mins. Courtesy of the artist.

Pure Imagination

Horses are and horses do. The rest is the product of our imagination.

–Andrea Tarsia30

If our cave-dwelling ancestors feared, revered, and exorcised the animal spirit by making drawings on cave-walls, today we seem to desire closeness to the spirit, if not the creature.31 Animals seem to promise a short-circuit access to the quick of life, to something authentic. Working from the tension between our fear and desire, Hilja Keading’s multi-channel The Bonkers Devotional (2007) records a live black bear and the artist coming to terms with each other inside a green-walled cabin. Quick shifts of perspective afforded by the handheld camera make overwhelmingly present the bulk of the bear, breathing loudly, as if it were squeezed into a dollhouse. Even in tight quarters we sense the initial distance between the two, symbolized in their occupation of different screens. Paradoxically our visit to the dual-screen dollhouse is sheltered by camouflage netting above our heads, as if in a bear’s lair. The internal drama of this dreamlike sequence is abruptly interrupted with close ups of quivering aspen leaves. We are firmly placed in the space of the mind, where the bear and Keading symbolically reflect and refract each other.32 The unexpected presence of the bear in a cabin intercut with that of the artist suggests aspects of her self emerging in unanticipated ways and places. We do not know if she is culture inviting nature in, or if nature has barged in. The animality we dread and crave is externalized in Bonkers, the aptly named bear; and as if to undo the dehumanizing dislocation of the animal spirit from our world, the artist has arranged this short devotional service to it. We are encouraged to have faith in a world where art can show us the way to becoming respectful roommates.

Corinna Schnitt, still from Once Upon a Time, 2006. DVD, single-channel, 25 mins. Edition of 7, 1 A.P. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Olaf Stuber, Berlin.

Primat and Keading interact with animals in person, in their own worlds, more or less on their own terms. Delightfully, the animals in Corinna Schnitt’s video Once Upon a Time (2006) are let into a suburban house without anyone home to hold them to scripted activity. It brings to mind Karen Knorr’s photographs from the Fables series, started in 2003, for which she staged taxidermic wild animals in palatial rooms reconstructed at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. Knorr said: “I like the disruption of animals in this pristine museum where they don’t belong. If they were real they would pee and crap on the furniture, they would annihilate the space.”33 In Schnitt’s fairy tale opening, no story gets told and our conventions are gently trashed. The motorized revolving camera offers a continuous panorama of a suburban living room from an unusually low vantage point. Then the menagerie enters, one by one.34 Think of the work as a repurposed merry-go- round, steadily rotating. The ducks circle past the coffee table with a sense of entitlement. The goats munch on a plant pulled down with its pot. A cow slurps from the goldfish-bowl. One curious kitten even looks straight at the camera. Fables famously have morals and explore human vanity. Once Upon a Time does not seem to enforce one, leaving the work generously open. Instead of animals in their proper place and behavior, we enjoy a lyrical overlay of two close impulses, to make a home and to domesticate animals. Here the respectful roommate fantasy is quietly modified. Normally these animals are allowed into the home as meal or pet; when instead we let them in too close, they do not behave like you and me.

Humans might tolerate animals disturbing their home, but such domestic disorder does not suit a spider. In Gift/ Gift (1998), we see Nina Katchadourian’s embroidered insertion into a web, the letters G-I-F-T in red thread, being undone and rejected by the spider, keen to restore his demesne to its silky glory. It is an ironical trick on the spider, whose ability to read is questionable. The doubling of the word “Gift” in the title conveys our balancing act with nature, a doubled performance of giving and expelling the G-I-F-T. As part of a series called Uninvited collaborations with nature, this work confronts human inadequacy even when we have the best intentions. Unlike our attempts to mend a bird’s broken wing, our gifts to such an alien creature lack understanding and are therefore a nuisance. To paraphrase the quotation above: the spider is and the spider does. The rest is the product of our imagination.

The Utilitarian Gaze

A number of commemorative projects honor animals for their occupation—as lab rats, space-dogs, and Hollywood performers. Although this work is not pictured in the artworks, they felt out of place in an exhibition about interspecies art. Furthermore, several projects did not take into any account the specific animals that were being used in the works’ execution and were more about human or scientific use-value and point of view. In some cases, that was the point. In Carlee Fernandez’s 7200-Buffalo and 7100-Goat (both 1999), a neatly sliced buffalo head gazes up from either side of a coat bag and a goat is refashioned as a rolling piece of luggage, complete with horns, as if to protect packed belongings. Fernandez lays naked the horror of homo utilis, in a neat embodiment of humanity’s baggage. By contrast, in Beatriz da Costa’s PigeonBlog (2006), pigeons were blithely yoked to radio transmitters that kept real-time track of local pollution levels. The work’s most perplexing aspect was the presentation of three taxidermic pigeons with the radio transmitters; the birds will never fly, the transmitters will never function. These memorial portraits betray a lack of confidence in the artistic status of the project and the credibility of the scientific work the birds perform. As a work of science the project justifies itself, but it is important to ask: how does it enrich us to call this either art or collaboration?

Collaborating Needs and Desires

We need animals. Animals don’t need us, but we need them. We constantly look for any kind of connection we can possibly get to them.

–Britta Jaschinski35

With the wholesale valorization of relational aesthetics by artists and critics, the social dimension of participatory work is predominantly seen as an unqualified good. So, collective creativity is embraced and individual authorship relinquished.36 In that spirit, the curators of Interspecies Art have adopted an inclusive spirit to quiz power relations between humans and animals by extending the notion of community to animals. In a way, the exhibition Interspecies Art itself is science fiction: forward-looking and hopeful in its belief that artists can collaborate with animals.

Two projects did take the idea—if not the issues—of collaboration literally, although their presentation was text-dependent and at a remove from the viewer’s experience. Natalie Jeremijenko’s OOZ project (2009) takes care in how it addresses and involves bats, among the denizens of OOZ (conceptualized as a zoo without cages). Bat motion detectors and a human/bat light interface are installed on the High Line in Manhattan. The interface consists of light switches that people can toggle to illuminate the bats for viewing and likewise bats can toggle to illuminate people for viewing. Instead of investigating a site of bat expertise, say echolocation, once again human expertise in visuality is privileged. The text and video in the Sweeney presentation explain how the umbrella-shaped robotic bat prototype emits bat-like utterances with which to communicate with the bats on their terms. But in the Sweeney installation the prototype lies mute, unused by human or bat, hung from the ceiling as a sculptural artifact.

Lisa Jevbratt, Interspecies Collaboration (installation detail), 2009. Image from project by Masha Lifshin and her cat, Mixture. Submitted through online, interactive component of installation. Courtesy of Lisa Jevrbratt and Masha Lifshin.

Lisa Jevbratt collects the work of her students under the rubric of Interspecies Collaboration (2006 to present). The students’ projects directly tackle the impulse at the heart of this exhibition. There is not space here to fully discuss a show within a show, but in questioning why art should be the exclusive province of homo sapiens, these works had promise. The creation of interspecies artifacts and behavior provides a potential space for interspecies communication; Masha Lifshin and her cat Mixture’s collaboration to create and use “Scratching play post construction” provides exhibit A. Cori Arnold’s experience running with her dog in circles and inducing vultures to circle with her, and later her husband’s similar experience, provides exhibit B. As she notes, “This was by far the most astonishing thing I have experienced in a long time. To see the non-human animals using a play-like flight motion and following the pattern of my dog and husband was what I felt a collaboration accomplishment.”37 In Interspecies Art, Jevbratt presents her work as the relational task of encouraging her students to collaborate with animals. And yet, she alone gets credited in the exhibition’s program. Is this an oversight, or does this assert a particular power hierarchy of collaboration in art, with authority decreasing from professor down to student down to animal?

Lisa Jevbratt, Interspecies Collaboration (detail), 2009. Image from The Turkey Vulture Project by Cori Arnold. Submitted through online, interactive component of installation. Courtesy of Lisa Jevrbratt and Cori Arnold.

The curators of Interspecies Art have put together an exhibition wherein we are encouraged to wonder how far the animals might come into our communities. The artworks do not speak in a single voice, being sampled from a field that is enormous and complex. But the collection of works does not present a unified argument either. A consideration of the works in the exhibition points to a dilemma facing any artist or curator of interspecies art: you want to give animals their due, however you are unable to give animals their due when the human point of view interferes every time. As the animal theorist Cary Wolfe says: Theory, if done “well enough,” will eventually discover that other animals are not other in the sense of belonging to some wholly foreign “outside,” but rather constitute a radical difference and alterity that structures “the human” in its very core.38 Why do we care about the categorical differences that persist in the world—art, science, animal, human? How can we best address them, how can we redress them? The Intelligent Design: Interspecies Art exhibition does not blow the divide wide open, but just might trace early, anticipatory cracks.

Neha Choksi is an artist. She lives and works in Los Angeles and Mumbai.