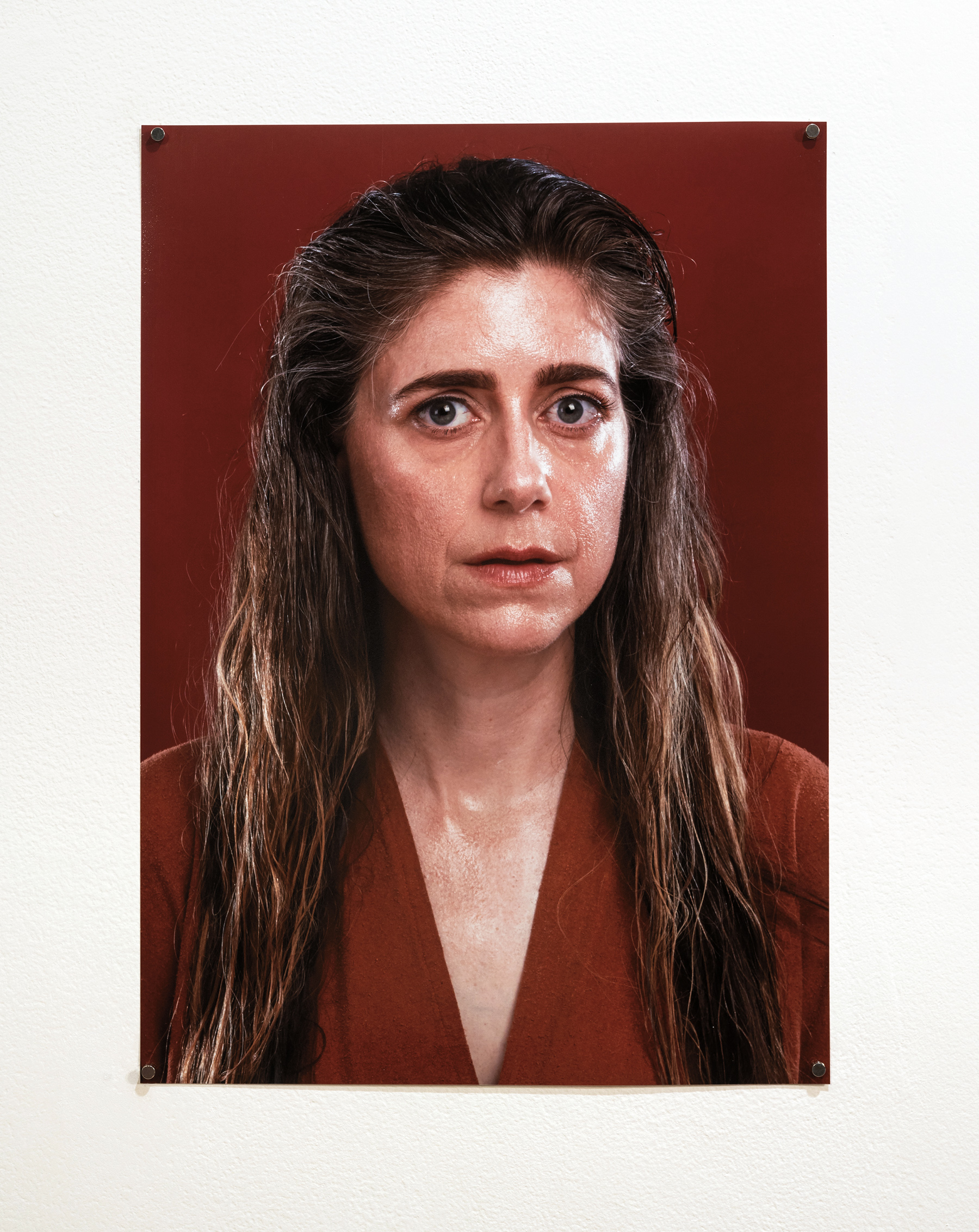

Anna Mayer, Retort (Glint), 2018. Inkjet photograph, 12 × 18 in. Courtesy of the artist and Adjunct Positions. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

On December 1, 2018, Poppy Coles and Candice Lin accompanied artist Anna Mayer to the burn areas of the Woolsey Fire in Malibu, California, looking for the sculptures Mayer placed there ten years earlier as part of her ongoing project, Fireful of Fear. On December 21, 2018, the three met again to discuss this project, in the context of Mayer’s recent exhibition Admit, Emit at Adjunct Positions, Los Angeles. The conversation that follows has been edited for print.

CANDICE LIN: Anna, I want to start by describing and responding to your exhibition Admit, Emit, at Adjunct Positions, before beginning our conversation about the recent changes to your ongoing work, Fireful of Fear.1 In the gallery’s garage space, two cylindrical sculptures occupied the center of the site; they were portable kilns made of ceramic fiber and sheet metal with patterns of leaves and insects cut out of them. In our correspondence, you mentioned that these designs were not, as I supposed, stylized images of nature, but are a reference to the patterns of textiles that were associated with Victorian mourning wear. As people who were grieving started to transition out of all-black garments, they would introduce small flecks of white or gray into the black. The delicate patterns indicated the slow transition out of mourning. Two ceramic sculptures hung on nearby walls. They were intricate systems of tubing, resembling a prehistoric armature for the bottom of stools or an apparatus for artificial breathing. Their surface was patterned in tendrils and rivulets, almost lichen-like in appearance. I read on the accompanying list of works that those pieces were fired using an Eastern European process called obvara, in which the molten ceramic is pulled from the kiln at 1650 Fahrenheit and dunked in a living, fermenting slurry of yeast, sugar, flour, and water, creating chance organic patterns. I thought about how a small amount of starter, or mother, is often used to accelerate the fermentation process, or to share or pass down a strain of fermented culture through a circle of friends or generations of family. Up the stairs, in the garden above the garage, I passed a hole dug into the earth. This, I was told, was where one of the tubular ceramic sculptures would be buried at the end of the show. On another part of the property, a hole for the second sculpture awaited. The hollow interiors of these sculptures were coated in lime that would gradually seep into the earth, making it barren “indefinitely,” according to the press release.2 The other exhibition site, inside the house, featured a wall-sized photo of a house and street (similar to the house I was in) that was covered by a mudslide. Across from this image were self-portrait photographs of you, sweating and glowing in one, and cold and pallid in the other.

Your exhibition haunted me for weeks after I saw it. I kept thinking about the ways that you engage ceramic processes that point to larger geological processes and scales of time: the fire of the kiln like the wildfires of California, unleashing mudslides and piles of clay to be formed into new shapes and sedimentary bodies, and the implication of your own body in all of this. I kept thinking about the strangeness of your portraits: your body, another kind of clay, put through transformations of heat and coldness, passion and melancholy, bearing witness to that same process occurring on a macro level in the environment that surrounds us.

David Prince, the artist who runs Adjunct Positions, said that you fired the ceramics on site, on the sidewalk of the Highland Park neighborhood. He told me that, as you dunked each molten piece of clay into the yeast slurry, the whole street smelled faintly like bread, and some people came by out of curiosity. I thought about the time you created a pit fire in my backyard, filled it with ceramics, and hosted a group of people who circled the fire in communion. You brought us together around fire, and we became, like the ceramics, transformed through this meeting.

You play with this potential for transformation in another work—the decadelong, ongoing project Fireful of Fear. Could you describe that project?

ANNA MAYER: Fireful of Fear started in 2008, when I placed 12 ceramic sculptures—torso-sized slabs inscribed with text—in the landscape around the canyons of Malibu, California. The idea was that they would remain there, where I placed them, until they were fired by wildfire. I send a yearly email to a group of people where I update them on whether any of the sculptures have been fired yet. The emails are also an update on my psyche. They feel a bit like a diary entry or holiday letter, where I’m indicating my current state of mind, which is inevitably some combination of hopeful and totally despairing.

I also send a postcard each year to a much smaller group of 12 people. Well, it’s 11 people now because two of the people on the original list have passed away. Michael Asher was the first person to pass away, and I chose someone else to get the mailing each year in his place. But when my father passed away, in 2016, I didn’t choose anyone new. So, it’s 11 people. On the annual postcards, there’s an image of one of the slabs in its unfired state.

Admit, Emit, installation view, Adjunct Positions, Los Angeles, September 23–November 10, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Adjunct Positions. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

A sculpture in the process of being buried on the grounds of Adjunct Positions gallery. The lime plaster on the ceramic will further alkalize the local soil, effectively preventing any growth above it indefinitely. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Anna Mayer.

None of the works were fired until the Woolsey Fire in Malibu in November 2018. It was a major event that burned the majority of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and destroyed hundreds of structures in the area. Three people died. It looks like six of the twelve slabs were placed in the Woolsey Fire burn areas. We retrieved two of them on December 1.3 Everything has shifted a lot, just in the last couple of months, around the project because it was a decade of waiting and tracking the fires in the area. And, because of the project, I’ve remained attuned to the phenomenon of wildfires in the West, which has definitely been ramping up in the last several years.

POPPY COLES: Can I ask a question about the postcards? The images of the slabs, did you go out into the landscape to photograph them each year, or were they pictures that you had taken before you placed them?

MAYER: They were pictures that I took before I placed them. People often ask me when they learn about the project, “How do you keep track of the works? How often do you check on them?” And the answer is, “Not very often.” It’s never really been about that. It hasn’t really been about caretaking the objects. The work has lived as a proposition, as a conceptual gesture. Prior to November 2018, the only images that existed were the 12 images of the slabs before they were fired. The first formalized check that I did was in 2016. That was eight years in. The process of the piece isn’t results-oriented, where I’m moving them around to optimize their chances of getting fired. I put them out there, and they’ve stayed put, experiencing whatever happens to their environment. It might be fire, or the groundcover growing over them. Or they might get moved by some other event.

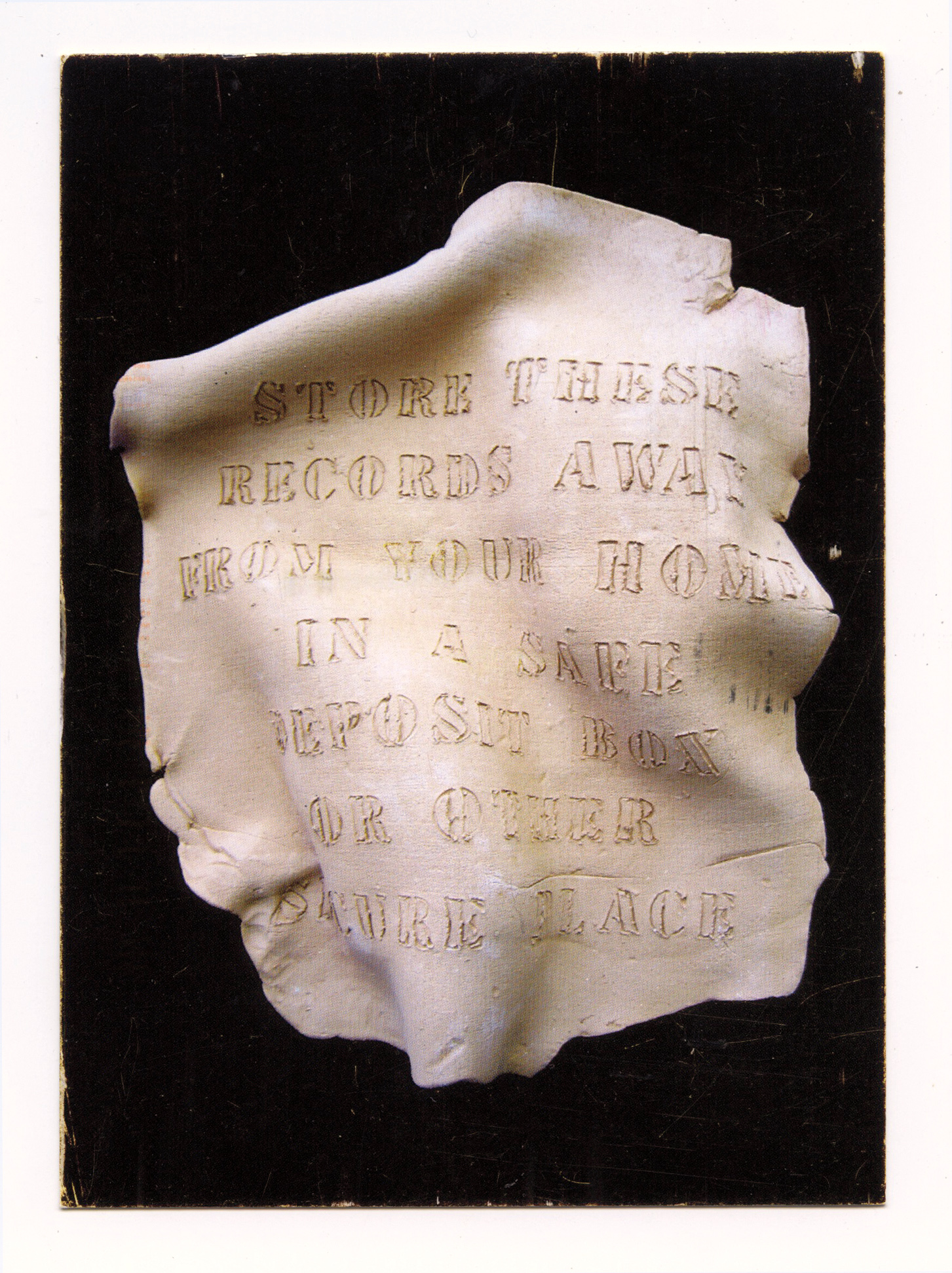

Anna Mayer, second anniversary postcard for the Fireful of Fear project, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

LIN: You described the ceramic sculptures as text slabs. Can you just describe how they look a little more? I believe some of them are kind of organic and rumpled in shape. What texts are written on them?

MAYER: The text is carved in. It’s a font like the M*A*S*H font. I can’t remember what it’s called.

LIN: The stencil font, right?

MAYER: The stencil font. That’s right.

LIN: Is that an important reference? I just thought it was a stencil font.

MAYER: I guess I always think of that font as having this army reference. There might be some loose connection there because my dad was in the Korean War and M*A*S*H was filmed in the Santa Monica Mountains, I think.4

The long, long history of ceramics is a major area of research for me. I’m interested in it as much as I’m interested in the history of art. Before paper was invented, daily accounting records in, for example, Assyria, would be kept on slabs of clay. The slabs wouldn’t be fired, so they could be reused indefinitely. Water would be added to erase the slab and allow a different day’s inventory to be recorded. When the villages would get plundered and burned, these slabs would harden and the accounting of how much grain, or whatever there was, would be preserved for posterity. I was really interested in that. We have all of these artifacts of really mundane information because of war, basically.

The text in my work is from different sources. Some of it I wrote, and some of it is found. There are a couple of statements that are somewhere in between. There’s a line from a lecture I saw by Alain Badiou, the philosopher. There’s a lyric from a Simon and Garfunkel song. One slab has a line from a Vietnam era poster, with the question: “Would you burn a child?” and the answer: “When necessary.” And then, there are some texts that I wrote. One of those is “A perfect country would have more of me.” Another is “Fuck the horizon.” Some of the text deals with the preservation of culture and of property. “Fuck the horizon” is in reference to Western expansion and imperialism. It’s a wide range of topics.

COLES: Did you figure out what the one that was broken said? Can you talk about the two that we found so far?

MAYER: Yes. The one we found off of Kanan Dume Road has text taken from a property insurance document. It says, “Store these records away from your home in a safe deposit box or other secure place.” The one that was in Solstice Canyon says, “There are territories beyond your conceptual and perceptual limits.” That was the one we were trying to put together and make sure we had all the pieces for. I was amazed that it was that particular slab that we had to reassemble.

LIN: That was the one that was buried under the dirt.

MAYER: Yes. I still haven’t figured out what happened. I don’t understand. I don’t know if it had been partially buried for a while.

Anna Mayer, Fireful of Fear: There Are Territories Beyond Your Conceptual and Perceptual Limits (Tropical Terrace), placed in 2008 and fired in 2018. Wildfire-fired ceramic, 19 3⁄4 × 15 1⁄2 × 3 in. Photo: Poppy Coles.

Candice Lin digging for Anna Mayer’s wildfire-fired ceramic sculpture in Solstice Canyon, Malibu, December 1, 2018. Photo: Poppy Coles.

Anna Mayer searches for one of her wildfire-fired sculptures in the scorched landscape of the Backbone Trail, Malibu, January 1, 2019. Photo: Poppy Coles.

Anna Mayer, Fireful of Fear: A Perfect Country Would Have More of Me (Escondido Canyon), placed in 2008 and fired in 2018. Wildfire-fired ceramic, 18 × 15 × 3 in. Photo: Poppy Coles.

LIN: Do you remember, when you went back in 2016, if you found it, or was it buried already and lost?

MAYER: I don’t think I found that one. I remember being confused about the location. And I felt confused again when we got to that site a few weeks ago. The 2016 check was me making sure that the general area of each slab hadn’t burned yet, rather than laying eyes on the actual ceramic. It was clear that Solstice Canyon hadn’t burned then and, so, I think I stopped looking.

LIN: It’s amazing to think about how much the landscape has changed during those ten years. When you were looking for them, you were talking about things you remembered from the landscape, like, “There were Manzanita bushes.” And you held your hand up chest high. Then I said, “Maybe these burned things were Manzanita bushes?” But they were over our heads, about eight or ten feet high. Can you describe how you feel now, several weeks after we were there?

COLES: Yes, what was it like to wait for something to happen and not know whether it would? I see that act of waiting, a long time, ten years, as becoming more important than the firing that occurred. This feels especially true, from what I understand, of the letters you wrote each year. Your updates on the slabs became a framework in which to think about other things and process other experiences happening in your life. Things that happened while waiting, but not the thing itself. You said that over time the slabs began to feel like they weren’t real anymore. Or, at least, their materiality became less important. How does it feel now that some are actually fired, and their object-ness has become present in your life again?

MAYER: While the fires were happening, I felt really sick about it all. When you live in Southern California, you track these fires and are affected by them, at the very least by the smoke that they create, and sometimes from knowing people whose lives or homes are directly affected. So, that was very real for me. Also, I’m currently living in Houston, having arrived there right before Hurricane Harvey hit. These catastrophes are devastating.

By the time we went to look for the slabs, it was established how much damage had been done, and how much loss of life had occurred. The Woolsey Fire in Malibu was so affecting in part because it was happening at the same time as the Camp Fire up north. There was huge loss of life in Paradise, California. An entire town was pretty much wiped off the map. These were major fires. By the time we got to Malibu, all of that was known, so I wasn’t as actively upset. When we found the slabs, I just felt really surprised. I wasn’t expecting it. I think I’d always conditioned myself to understand that they might not be there when I went to find them. The work is outside of me, because I’ve had to take my hands out of it so much. And, then there was the extreme change in the landscape in Malibu, since I’d last been there. That kind of shift is fundamentally shocking.

Now I find myself thinking fairly clinically about what it means, now that there is an object for viewers to see. It’s much more of a closed loop. I’m wondering whether it shifts the focus away from the proposition of the work and the politics of it? Can the open-ended gesture of the piece still be active?

Regarding the larger question about waiting: the way the work has existed for the past decade is that people hear the sound bite of the project and then they go through a process of thinking about the landscape, then thinking about me in the landscape placing all the slabs. Then they think about the sculptures. And then, I feel like, what is left to think about is me and my desire. People have to think about me waiting.

On the day that we were out looking, we talked about how the project was a critique of the overdevelopment of an area where wildfires are inevitable and even necessary for a healthy ecosystem. I was inspired by Mike Davis’s writing about this.5 Because of how valuable the land in Malibu is as real estate, there’s been a huge amount of building on land that burns regularly. Fire suppression doesn’t work, and then a lot of resources are put into saving the homes there, as well as rebuilding them once they burn. So, the project came out of all of that initially, along with my desire to respond to the history of West Coast ceramics. I also wanted to make a piece of Land art on a human scale. But because of how it’s all unfolded, and because of this really long time period, the piece is also about desire, and the act of waiting. Do you know Faith Wilding’s piece, Waiting (1972)?

COLES: I don’t.

MAYER: It’s a monologue written by Wilding that she recites while rocking back and forth. She performed it in the 1970s, and it’s about all the things that a woman waits for.6 Faith is on my mailing list for the yearly updates, and she actually pointed out that I was talking about waiting. This was maybe five or six years ago.

LIN: I think it’s interesting because it brings me to the question I had around the politics of your work. Because it’s not only about waiting but also about witnessing. Right? You’re not waiting in a vacuum. You’re waiting with people watching you wait. And so, then it becomes more about a kind of vigil. Or, a wake.

Something that’s always struck me about your work is that it’s political in this way that doesn’t feel like it has a clear didactic or resolved message that it’s conveying. But, with Fireful of Fear, there’s this sense of the inevitability of ecological devastation that you know has no easy solution. So, when you’re talking about the fact that some of these ceramic slabs have been fired, and you were asking if it shifts the focus from the political proposition of the work to a false sense of resolution, I feel like it doesn’t, because it seems like one piece of this idea of witnessing. I’m wondering about the act of witnessing in your work, because it’s something you’ve written about in some of the letters. Your work seems to ask the question, “What can one do to affect some kind of political stance or change when catastrophe is inevitable?” In this sense, your work feels realistic, but not nihilistic or resigned.

Anna Mayer with Fireful of Fear: A Perfect Country Would Have More of Me (Escondido Canyon), placed in 2008 and fired in 2018. Wildfire-fired ceramic, 18 × 15 × 3 in. Photo: Poppy Coles.

MAYER: Fireful of Fear aligns itself with the idea that wildfires are inevitable. Fires become catastrophic because we build in their paths. So, Fireful is on the side of fire being generative. It still is about that. But, I think it’s also about modeling, or rehearsing, or experimenting with refusing to do anything. Just waiting. It’s an extremely conservative strategy, as an artist.

COLES: Instead of taking some action, you’re allowing something to be acted upon.

MAYER: Part of what I’m doing is grieving. Grieving the devastation of global warming while refusing to make it a spectacle.

LIN: And maybe you’re refusing as an individual to take some kind of action, because it’s a problem that can’t be solved by one individual’s action. Yet you are taking an action by creating this community of people who are waiting and witnessing the fire in this intimate way through your project. I might not have felt as intimately about the wildfires when I heard about them on the news, but because I have this relationship through you and these ceramic slabs, it shifts my emotional relationship.

MAYER: Right.

LIN: It does exist as a kind of collective action, but it’s not action in the usual sense. Maybe that’s why I brought up the idea of the vigil, because I feel like a vigil is a way of having collective action, but it’s not spectacularized.

COLES: It’s interesting because there is both an intimacy and a distance present in the work. You talk about the witnessing of something. But, it’s not a direct witnessing, in that, it’s not people witnessing the fire in real time. They are witnessing at a distance, through you. The people that you’ve been writing to have a connection to the work and to the fire through you, and now through these objects, which bear all of the signs and traces of fire. The smell, and the texture, and the color, there’s an intimacy in being in contact with them, and then, there’s an intimacy in their relationship to you and how they have provided a frame in which to reflect on your life. But, neither you nor this group of people have witnessed the fire itself, or at least, the firing of the slabs. So, there’s a distance there too.

LIN: In this idea of scale and intimacy, I was thinking about the work in relationship to mourning. You spoke about how, during the ten years of this project, you lost several people you knew: Michael Asher, then your mother and your father. I know you’ve been making a lot of work that is about a deeply personal experience of mourning and grieving. But that seems tied, I think, to this kind of larger, planetary ecological mourning. This seems to be related to what Poppy is saying around intimacy and distance— these different personal and global scales of grieving.

MAYER: One of the texts on the slabs says, “It would be one thing if I weren’t doing this with you,” which is a quote from a yoga instructor, in a class I attended in 2007. We were doing something really difficult, and he was instructing and explaining, and correcting, and cheerleading, and doing all the stuff yoga teachers do, all while he was doing the sequence of poses with us. I guess he must have registered someone in the class making a face like, “Oh, man. This is the worst.” That was when he said, “It’d be one thing if I weren’t doing it with you.” I was so struck by that at the time. It’s continued to be a kind of touchstone for my interest in enactment and relational strategies. A lot of my work is attempting to produce embodiment. Initially, it was through using optically exciting graphics and trying to engage or implicate the body through visual tricks like trompe l’oeil. Once I started working in ceramics, I was able to work in these ways pretty fluidly, as well as with the bodily aspects of the material, the way that it can be plastic and then go through all of these different states of being. There is a strong connection between ceramics and ritual in many regions and cultures. Ceramics is so social.

My pairing of language with ceramics is about that sociality. The sculptures slow down the act of apprehending an idea. Reading words carved into clay is different than taking in those printed on a piece of paper, or hearing them spoken in conversation. I think I’m a little bit off track. Can you get me back?

Screenshot of Anna Mayer’s seventh anniversary email for the Fireful of Fear project, September 26, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

LIN: I think the question was more around the scales of relationship to the world, or to each other, or to the work. We’re both struck by how, on the one hand, there’s such a tactile intimacy with the object, or with these letters your friends receive and the emotional content that you share. And on the other hand, the fires are on the evening news.

MAYER: The work has been unfolding over ten years, and all these life events have happened in that time, as they do. The work is so open that it’s enveloped all these other things. So, I don’t know, I’m not sure how to answer that.

COLES: It reminds me of what you alluded to, Candice, about grieving, or mourning, or death in general. There is both this intimacy with death, but there is distance also, because you can’t follow the person to wherever they go. It is the most intimate of things and the most distant and hard to reckon with. I don’t know if that resonates with you, but there seems to be a connection between these huge events, whether it be a wildfire, global warming, or somebody in your life dying. They are each about trying to grapple with the inconceivable.

Anna Mayer, Fireful of Fear: Old Epic Stories Handed Down Into the Hands of Storytellers (Charmlee Wilderness), placed in 2008 and fired in 2018. Wildfire-fired ceramic, 18 × 15 × 3 in. In situ, Charmlee Wilderness Park, Malibu, January 1, 2019. Photo: Poppy Coles.

LIN: It’s something that strikes me about the work too. That it really tries to take on these things that are not graspable, that are so overwhelming and extend over scale and time. You had talked to me when we were walking around about being influenced politically from an Ecofeminist lens. When you were just mentioning wanting to contribute to West Coast ceramics, or wanting to make a piece of Land art that was on a human scale, I was wondering if that Ecofeminist politic is something you are activating to intervene in those more, maybe, macho lineages.

MAYER: I was referring to the way that the slabs were dispersed across the landscape and I had to walk them out there. It was a very modest scale. The dispersal was about not making a monolithic statement. There is an Ecofeminist perspective that it’s harmful to present nature as something totalized or apprehensible. In alignment with this, I was very conscious about making something that was diffused and dispersed.

There’s also the issue of scale, for instance, Michael Heizer and the myth of the mad man in the desert making this massive monumental work. His rock, Levitated Mass, wasn’t installed at Los Angeles County Museum of Art until 2012, but my work is definitely critical of that lineage of Land art!

LIN: How do you see your work engaging the history of West Coast ceramics?

MAYER: I hope the work is sensitive to the very long history of ceramics in California; there were Native American people working here long before the well-known twentieth-century movements. The more recent history, which is often told as a dynamic between the Northern and Southern California movements (Funk vs. Abstract Expressionism), has given me lots to think about over the years. There’s a lesser-known Bay Area figure, John Roloff, who made these largescale, site-specific sculptural kilns in the early 1980s. The kilns were empty, except for the ground they sat on. So, the focus was on fire, and harnessing fire in relationship to geology. His work was very influential for me. I’ve done several works where the firing of ceramics is theatricalized and the social aspects of the material are emphasized. Obviously, Fireful is in that trajectory.

LIN: Thinking about the long lineage of ceramics, I’m wondering if there’s a connection between the history of ceramic slabs being used as records of accounting, and something you had written about in one of your annual updates. You wrote about a word that you coined—encount— and how you found yourself mistakenly repeating the word as incant. I was wondering if there was a relationship for you between encounting, being accountable, and incantatory practice?

MAYER: I came up with that word for the title of a series of fiber works that ended up being called Can Encount (2015). I made these large-scale photographic images through latch hooking. The images are made up of thousands and thousands of pieces of knotted yarn.

LIN: Oh, that’s similar to the ceramic slabs as receipts of purchases or records of debts owed, tying knots in a rope was another kind of receipt.

Anna Mayer, Can Encount (Deirdre), 2015. 24-color hooked rug, 34 × 41 × 1 in. Courtesy of the artist.

MAYER: Oh, yeah! Well, for me it was about sitting in one place doing this meditative thing. It was self-soothing. Making those textile pieces took hundreds of hours. I did a lot of the work at home, and at some point my partner Jake Dotson observed that, during those hours of making (over weeks and months), I wasn’t out doing harm. I wasn’t consuming resources or making plastic trash, or otherwise committing violent acts. I guess you’re getting a glimpse at the quality of our household conversations! I think it goes back to the idea of refusal. I don’t know if it is refusal exactly, but it’s marking time in a way that’s not about a certain kind of production.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about the idea of refusal because of the work at Adjunct Positions, specifically the ceramic pieces that were buried on the grounds of the gallery. They hold lime plaster, which shifts the pH of the soil so that nothing will grow above the sculptures, indefinitely. It’s a gesture towards what that landscape will become eventually, whether that’s through fire, or the end of humankind, or whatever. This really high stakes real estate [of the Highland Park neighborhood in Los Angeles] will become devoid of human-tended gardens.

LIN: I was thinking about incantation as a kind of repeated action, like tying knots, that gathers energy and repetition into the material it is focused on, through circling around it either through words or thread. But, what I’m hearing you say is that when you’re repeating these gestures, or putting these objects out into the world, your intention is an anti-intention. It’s a critique of the mandate to be productive that our capitalist culture emphasizes.

MAYER: Mm-hmm.

LIN: But, I guess I always thought about ritual incantation in my own work as being the way to make something matter, to put something into being. You know, using a method that isn’t a product-oriented one, but is another modality.

MAYER: Right.

LIN: So, even though there’s a kind of anti-productivity with your sculptures that makes the soil barren, it is still a spell for the future.

Anna Mayer, No End of Channels 3 (Astonishment Rather than Compassion), 2012. Underglazed ceramic, sealant, 19 x 22 x 2 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist.

MAYER: Well, those knotted fiber works, I made those, in part, in response to my No End of Channels (2012–ongoing) series, which are hollow pipes shaped into knots. Each one is modeled after a diagram taken from topology. I had been making those for a while before I had some pieces break at really inopportune times, and I became unsettled by the fact that the ceramic knots were not fully knotted or fully undone. This is a problem in the terms of knot magic, where tying a knot makes something happen and untying a knot reverses it. I was making these things that were frozen, in between. In contrast, every single one of the fiber knots in the Can Encount series could theoretically be undone. And then done again.

LIN: It’s also interesting that each of those individual knots, when together, become an image, right? And is this the series that is based on of your mother’s drawings, or wall hangings, that she designed based on Paul Klee’s work?

MAYER: It’s the same process. But Can Encount came before the Paul Klee-based series, Pale Clay (2016–ongoing). To make Can Encount, I gathered together objects in the studio or at a specific site. The images are based on photos of these groupings of objects.

COLES: It’s similar to what we were pointing to before in the Fireful work—that there’s this gap, an in-between-ness. The space between placing the objects and them being fired and a space between the knots being tied or untied. A space of potential. You talked before about not wanting to take action, to allow something to happen of its own accord. It feels like you are posing big questions, about history, and the environment, and life. And instead of giving an answer you are interested in the space left between question and answer.

MAYER: I think so. With something like global warming, I’m still, like a lot of people, clinging to the possibility that we can reverse these processes. You know? World leadership isn’t yet making that happen. I want it so much, in the deepest part of my being. With ceramics, up to a certain point, you can reverse the process. More so than with a lot of materials, you can undo your work until you fire it. It can be reclaimed indefinitely. And then there is this point, the point of firing, after which it’s going to be around for, likely, thousands of years.

COLES: The point of no return.

LIN: I keep thinking about how these non-gestures accumulate but perhaps take more than one lifespan to see the effect. But, they do become something. Like, all those knots add up into an image. And in the case of the ones that were your mother’s patterns, weren’t they designs she didn’t have time to make in her lifetime?

MAYER: Yes. She isolated these parts of Paul Klee paintings and she was knitting them. They were going to become part of some kind of larger whole. I don’t really know what it was going to be, maybe a blanket or something. She finished knitting about half of them. So, I’ve been following her patterns to make the Pale Clay textile works.

LIN: I’m thinking about the generational aspect of this Pale Clay work in relationship to you placing the twelve Fireful of Fear sculptures in Malibu. You might find some of them after the wildfires, but you also might not. Some of the slabs might be buried by displaced earth or be moved by humans and might not be found until generations later. And then, thinking about the obvara-fired sculptures in Admit, Emit that slowly leak lime and make the soil barren, it’s an action of infertility for future generations, right? So, there’s this timespan or genealogy in your work—it is dismal and hopeful at the same time, because it makes me remember to think beyond the scale of my own individual life.

MAYER: My awareness of this has increased as I’ve lost people. In an earlier conversation, you asked me about the “fog of consciousness.” I think it relates to what you’re saying about the vigil being a kind of collective action. I mean, brain fog is a medical phenomenon that can be brought on by trauma, or fatigue. I have experienced that. I think I’ve always wanted my work to engage more senses than just sight, and I feel like the fog is this moment when you can’t see, but it’s sublime in these other ways. It’s also a moment where consciousness can envelop you. This idea of being enveloped and working towards having a more collective consciousness is about the destabilizing of a fixed subject position. That can be so confusing. Or can feel like you’re losing sight of something. But it’s a necessary thing.

Anna Mayer’s practice is sculptural and social, with an emphasis on hand-built ceramics. Her methodology emerges from enacting formative site-specific projects in Southern California and her interest in the relationship between speech and consciousness. She is an Assistant Professor of Sculpture at the University of Houston.

Poppy Coles is an artist and the Managing Editor of X-TRA.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at Portikus, Frankfurt; Bétonsalon, Paris; and Gasworks, London. Lin is a member of the X-TRA Editorial Board.