The material of the medium is an electron. Its mass is 1/1835 the mass of the hydrogen atom. Though it moves so swiftly it cannot be perceived by the eyes of man, it is finite. Its effects can be studied upon the surface graphs of oscilloscopes. And these effects are seen as sine curves and waveforms. Synchronization, amplitude, amplification, and modulation are what electronic circuitry is mainly about. It’s also about storage and delay.

But mostly, it’s all about time.1

Television, one version of the story goes, was invented in San Francisco.2 Philo T. Farnsworth, the 14-year old boy genius who diagramed the device in 1920 on the blackboard of his schoolhouse, brought his invention to life seven years later in his Green Street workshop. On September 7, 1927, Farnsworth instantaneously beamed a “minimalist straight line” from one side of the studio to the other.3 The straight line was not a surprising first image for electronic television. It was, in fact, indigenous to the screen, whose images are produced by an electron beam racing back and forth across an invisible raster grid. A year later, Farnsworth’s investors were no longer satisfied simply with his conquering of space and time; they demanded profits from the “gadget.”4 Farnsworth then produced another image on the screen for his backers: a dollar sign.5

Farnsworth’s two early images—the structural line and the dollar sign—neatly sum up the course television would take as a medium. Scientific and artistic experimentation would work at the service of profit. Soon after Farnsworth’s successes, American radio broadcasting corporations would become interested in television technology and its potential to capture new markets with “illustrated” radio programs. By the end of World War II, television would take off as a mass medium and become a regular part of the ambient sights and sounds of the American home. Forty years after Farnsworth’s transmission, the Baby Boomer generation, the first “raised” on television, had come of age. In the United States, this coincided with the Viet Nam war and the protests against it, the Civil Rights and Feminist movements, the 1967–68 marketing of the first portable video camera, Sony’s Porta-Pak, and the Rockefeller Foundation’s somewhat sudden decision to sponsor artists’ programming on public television. Between 1967 and 1977, the Rockefeller Foundation donated more that $3.4 million to public broadcasting stations (primarily WGBH-Boston, KQED-San Francisco, and WNET-New York) to begin experimental artists’ workshops in their television studios.6 With new funding, new equipment, and new generation of experimenters, San Francisco, once again, became the site of a televisual revolution.

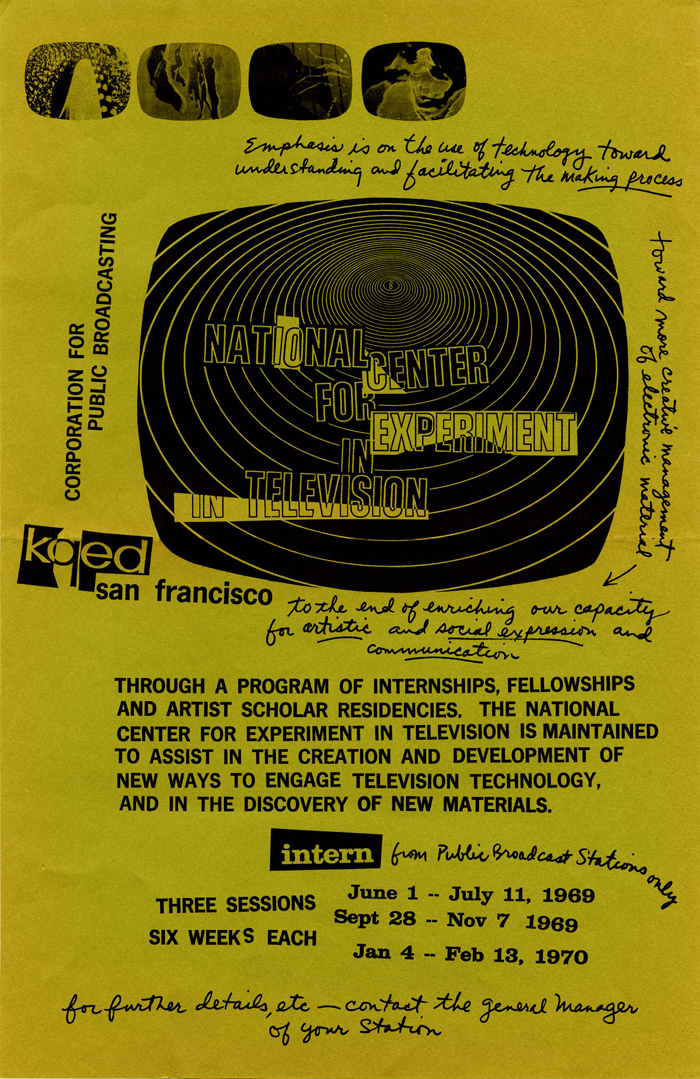

In 1967, in the midst of these conducive circumstances, Brice Howard moved from New York to San Francisco to become the director of KQED-San Francisco’s Rockefeller Foundation-funded artists’ workshop, The National Center for Experiments in Television.7 Under Howard’s leadership, NCET produced some of the most outlandish, innovative, and psychedelic work ever to screen on TV. Howard invited a team of young painters, poets, musicians, and engineers to become video artists in residence at the station’s lab. Among them were filmmaker and physicist Loren Sears, painter William Gwyn, sculptor William Allen, designer Willard Rosenquist, Beat poet Joanne Kyger, and engineer Stephen Beck. Despite the radical appearance of the videos produced by the NCET artists, Howard predominantly framed the group’s work as a formalist investigation into the medium-specific qualities of video and television, which pointed back to Farnsworth’s electron lines, as well as to a contemporaneous legacy of Modernist methodologies in art history and criticism. While it is commonplace to frame the history of video art in the contexts of film, television, and photographic history, Howard and the NCET artists sought to separate the video image from these narratives and explore it as a new, unique artistic medium.

By the early 1970s, this agenda drew critical fire from eminent art-world tastemakers, such as Artforum editor Robert Pincus-Witten, who, for one, criticized their approach as too conservative. Consequently, NCET work has largely been relegated to the footnotes of video history.8 At “Open Circuits: A Conference on the Future of Television,” the Museum of Modern Art’s 1974 conference on the state of the new medium that included abstract, structuralist, experimental video artists and filmmakers, such as Beck, Hollis Frampton, and Stan VanDerBeek, Pincus-Witten described their work and its “deficiencies” as such:

The generation of artists who created the first tools of “tech-art”…refuse to acknowledge the bad art they produced. Their art was deficient precisely because it was linked to and perpetuated the outmoded clichés of Modernist Pictorialism, a vocabulary of Lissajous patterns—swirling oscillations endemic to electronic art—synthesized to the most familiar expressionist color plays and surrealist juxtapositions of deep vista or anatomical disembodiment and discontinuity.9

For Pincus-Witten, video was an inherently “reproductive” and narrative medium. While he does connect this work to Modernist traditions (albeit in their degraded “pictorialist” forms), he neglects to see these investments in formalism as a necessary step in establishing the material properties of video as a medium. The formalist investigations that took place at NCET in the 1960s and 1970s were clearly an attempt to practice a mass medium at the register of a fine art by subjecting it to a formalist reduction in the Greenbergian tradition, that is, to take very seriously the specific formal properties of video that distinguish it from the other arts.10 But the properties that Howard and the NCET artists located as the essential qualities of the medium were at odds with those typically associated with television and video at the time (and since). The Whitney Museum of American Art’s first two major exhibitions of video (David Beinstock’s 1971 show, A Very Special Videotape Show, and Video Films [1972]) were entirely dedicated to abstract work. By 1973, this work had disappeared from TV programming and museum exhibitions, and representation, narrative, and performance-based video art dominated the field, as they have continued to do.

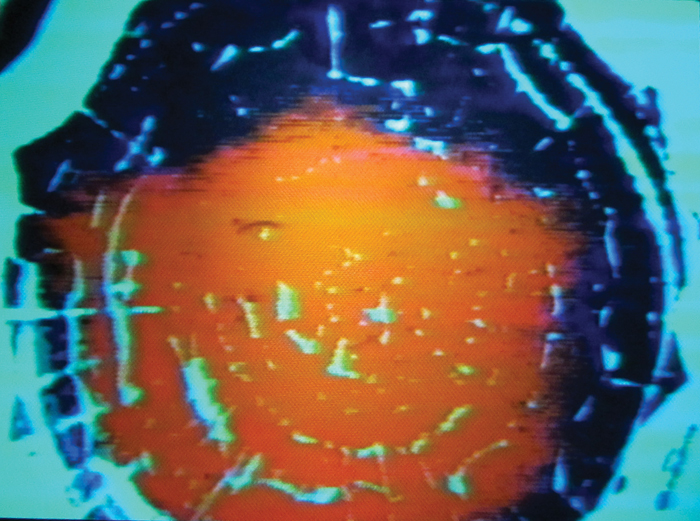

KQED/NCET, “A Visit to the Center,” 1973. David Dowe, Jerry Hunt, and Marvin Druckler discuss live video feedback. Video still. © KQED. Collection of The Pacific Film Archive. Photo courtesy of KQED and The Pacific Film Archive.

KQED/NCET, “A Visit to the Center,” 1973. David Dowe, Jerry Hunt, and Marvin Druckler create live feedback “mandalas.” Video still. © KQED. Collection of the Pacific Film Archive. Photo courtesy of KQED and the Pacific Film Archive.

Pointing at the Center

In 1973, KQED produced a curious program entitled “A Visit to the Center.”11 The segment opens with a blurred image that slowly resolves into a set of shapes. Three men—NCET staffers David Dowe and Jerry Hunt and a young visiting artist—are seated in a horseshoe ring of television sets with cameras pointed at the screens. The camera tracks around the outside of the ring and joins the men in the center, at The Center—one of the NCET production facilities. Their voices begin to be audible amid the electric hum of the room and its many devices. The three men are looking at the monitors. A voice rises above the din and says, “Wow. That’s nice.” Another answers: “Well, what it is, is a thing called feedback.” Looking at a TV image unavailable to the presumed at-home viewer, the young man describes what he sees: “It’s like there are two mirrors right next to each other, and you are looking into one of them and it just keeps going.” As he speaks these words, and without warning, the viewer’s vision is altered: the scene multiplies and stretches into a visual echo corridor of feedback. The broadcast image briefly illustrates their conversation. The men tinker with their cameras, and the scene then slips further into psychedelic swirls—doubled ghost images of the men and brightly colored pinwheels of feedback hover in the empty space of the room. The viewer listens in as the three men talk amongst themselves. The young man is the uninformed viewer’s foil—he does not know what feedback is. Hunt patiently explains the mechanical and mathematical forces that produce video feedback patterns; Dowe translates the technical language for the lay viewer and enacts them with a camera. Like the 1973 home-viewer, the visitor is seeing for the first time an inherent trait of live video.

The camera and its mimetic properties were so inextricably tied up in what it meant to be “television” or “video” that Rosalind Krauss’s famous diagnosis of video art in 1976, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” hinges on the ability of the video camera/monitor system to act like a mirror, and thus short circuit a traditional Modernist examination of the medium, exchanging critical reflexivity for narcissistic reflection. For Krauss, this substitution of reflection for reflexivity complicated the possibility for a formalist project in video. Even so, most video artists, she argues, “intended to disrupt and dispense” with the formalist critical tradition and to “render nonsensical a critical engagement with the formal properties of a work, or indeed, a genre of works—such as ‘video.’”12 Thus when Vito Acconci recorded himself “pointing to the center of the television monitor” in his 1972 tape Centers, Krauss claims he was attacking both the conventional logic of “pointing to the center” that “invoked the formal structure of picture objects” and “the kind of criticism…that takes seriously the formal qualities of a work, or tries to assay the particular logic of a given medium.” However, Krauss will argue that, despite his attacks, Acconci accidentally models and exposes the formal logic of video (as she perceives it) by showing that it is fundamentally a medium of mirroring and narcissism. It is worth noting that while it appears that Acconci is pointing at the center of the viewer’s monitor, the shot was made by pointing into the video camera, not at the monitor as Krauss claims. Krauss’s condemnation of video has to do, I think, with not seeing beyond the representational functions of video. She imagines distortion (i.e. Joan Jonas) and disorientation, but not abstraction or non-objectivity. This subtle oversight points to a need to reexamine her claims about video, especially with regard to the videos created at NCET during the earliest days of video art.

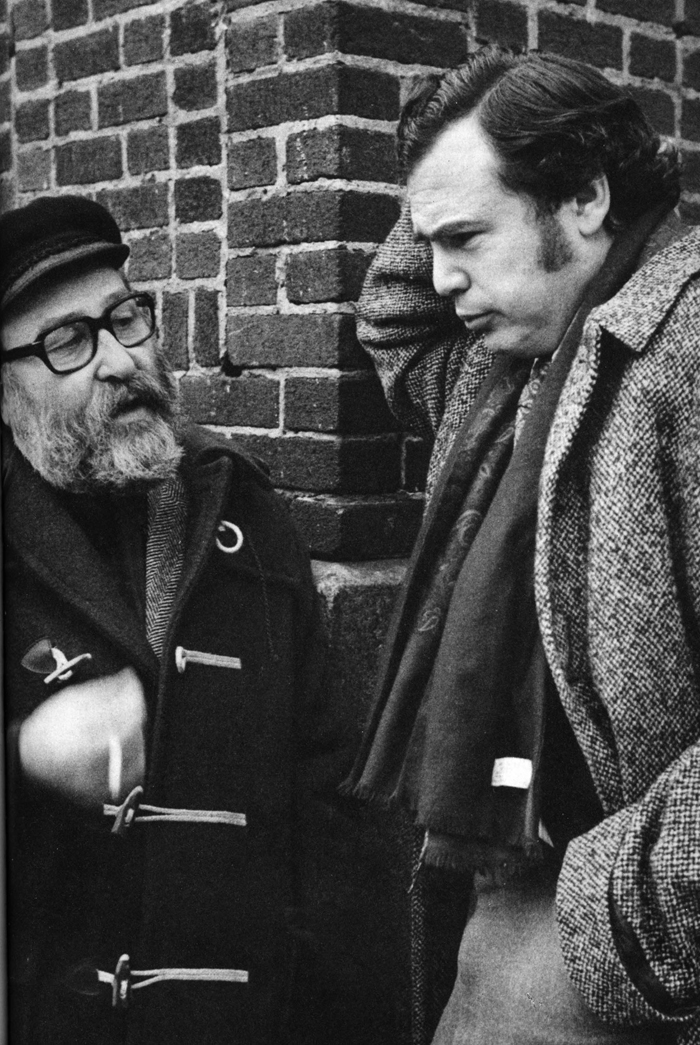

Penny Dhaemers, Brice Howard and Paul Kaufman, c. 1970. Photograph. © Penny Dhaemers. Collection of The Pacific Film Archive. Photo courtesy of The Pacific Film Archive.

Electronic video feedback comes in two forms. One is what Krauss describes: using the camera and monitor as an electronic mirror to respond and react to a live image, but this is not the only way the system functions as a mirror. (As noted above, the crucial difference between video and a mirror is that one needs to be in front of the camera rather than the monitor to use it as a mirror. That is, one needs to be displaced from the “reflective” surface to see one’s reflection.) The second form of feedback is more traditional; a system’s receiver is placed too close to the input, causing distortion. This form of electronic feedback, too, acts as a mirror, but of a different kind. By facing the live camera at its monitor, one can create a visual mise en abyme in which the image of the monitor recedes infinitely into the space of the monitor, just as two mirrors facing each other will. But each repeating image is a slice of time as well as space. Any event captured by the camera will tumble down the reflective corridor as well. Slight changes to the camera—tilting it on its side, adjusting the aperture or focal distance, adding an object—will echo through the image and pulse and distort the image. The representational image will begin to tumble and form the abstract, psychedelic “mandalas.” These “archetypical” forms of the video medium (per Dowe) are a simple means of divorcing the video camera and screen from the iconic and representational codes that usually govern them. In creating these circular, symmetrical patterns, the men self-reflexively and critically “point to the center”: to the NCET as a concrete location for production and to feedback circular structures as the conceptual framework for understanding video’s basic qualities. They point to the very surface of the screen in order to indicate its specific, unique properties, to indicate where one needs to look to see a different kind of televisual experience, and to stake out a case for taking seriously the potential of video’s electronic formalism. Working with feedback and the abstract images that video inherently tends toward is a means carrying out the Modernist self-assessment that Krauss did not think was likely or possible in the medium.

Rather than focusing on the mimetic properties of the camera and its ability to produce and transmit representational images, which dominated discussions of video’s formal character, the NCET artists turned their attention to the abstract, electronic structure of the cathode ray screen. They located the essential properties of video not in the live transmission of a camera image, but in the blinking pulse of the electron beam. By attempting to remove the primacy of the camera and its representational powers, Howard and the NCET artists engaged in an unexpected and provocative rethinking of what video was and could be. They created a genre of video based on the screen rather than the camera.

Beyond opening up a new avenue for what video art might become, Howard also turned television on its ear. While video and television are closely related material forms, they were quite distinct cultural forms in the late 1960s and early 1970s. All television images are video images. (Even programs shot on film must be transposed to video via a camera or tape for broadcast.) Electronic video cameras electronically transmit and reconfigure images on a raster screen for a dispersed mass audience. Video is both the base medium and the recording medium for television. As cultural forms, however, they were quite different. “Video” became known as a private, personal medium as opposed to the corporate broadcast and cable systems of “television.” While video, like television, could instantaneously transmit its live images from camera to monitor, it could only span the distance of the length of its cord. Additionally, the portable home video cameras that popularized the personal medium were not compatible with broadcast standards, and therefore homemade tapes could not be broadcast on the air without expensive transfers to broadcast quality tape or by using a broadcast camera to shoot off of a playback monitor. The artistic medium was, then, largely distinct from the broadcast form of television in terms of distribution and quality, if not in basic technology. NCET, as well as the artist-in-residency programs at WGBH and WNET, gave artists unprecedented access to broadcast quality equipment and to airtime. The Rockefeller-funded research programs extended the nascent field of “video art” into “artists’ television.”

Most discussions of the essential properties of video as a medium hinge on the device’s ability to transmit real-time representational images from one place to another by means of an electronic camera, and television’s ability to do so over long distances to a mass audience.13 NCET artists attempted to drive a wedge between the medium and its representational, cinematic qualities. In their experiments, they also troubled the idea of what it meant for an image to be “live.” Liveness no longer designated the transmission of a recognizable real-time image of people, places, or things from the television studio or scene of an event to the monitor, but referred to the live action of electrons on the surface of the viewer’s screen. By focusing attention on the electronic properties of the screen’s cathode ray tube, the NCET artists accomplished the kind of reflexive formalism that linked itself to classical epistemological investigations into the relationship between vision and reality.

Loren Sears, Loops, 1968. Video still. © Loren Sears. Collection of The Pacific Film Archive. Courtesy of Loren Sears and the Pacific Film Archive.

Willard Rosenquist with William Roarty and Warner Jepson, Lostine, 1974. Video still. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

The Surface of the Screen: Brice Howard’s Videospace

Five years into his tenure as the director of the NCET, Howard published Videospace (1972), a manifesto outlining his ideas for the future of television. Television, he argued, had been misunderstood as a distribution system rather than as a material. Television and video were not mere conduits (medium as translator or “something between”) as Krauss described, but were in fact a “space,” a surface, a material in which one could make, not just send, a work. Videospace was a space of dynamic, unfolding movement, but this movement was not one of “carrying.”14 The further video makers separated themselves from the trappings of theater and cinema, the closer they would come to videospace. While Howard never cited Greenberg’s work, he appropriated the art historian’s rhetoric and project of reductive formalism, even if it did reveal video as an “expanded” medium rather than a rigorously specific one.15 Television had its own “unique characteristics and qualities”; but only recently, Howard claimed, had it been “thought of as a medium independent of other media. To such an extent that it has been thought of this way previously, the histories of theater, journalism, motion pictures, and radio have been essentially influential.”16 Television systems were designed to distribute a commercial product consisting of representational images, but this design choice did not define the medium; it only pointed to how culture had chosen to use it. What had not influenced the standard concept of television was, however, the history of other fine arts and the pursuit of each art’s essential qualities.17 The term “videospace” and the independence it claimed for television and video from other commercial and artistic media allowed Howard to point to the formal properties that make television unique among the arts.

While television was, in Howard’s mind, clearly an artistic medium, its potential had not been realized—or even recognized—by the industry or the general public. The reason for this, he claimed, was that television had been formally and aesthetically crippled by the commercial conventions that governed it. Producers learned to “make television in a certain way in order that the system be maintained.”18 According to Howard, that system was flawed on two counts: it was organized around securing profits by delivering a product (this was the case even for public television, which needed to attract corporate and individual sponsorship), and it understood television’s essential quality to be the instantaneous “transfer of photographed experience from one point to another.”19 To Howard, focusing on television’s capacity for collapsing space and time in an act of representation was missing the point. To understand the medium of video, we must rather “learn to manipulate the materials of the medium, the flow of electrons. We must go with process. And we must infuse this process with our own instantaneous awareness. Our own experiencing.”20

“So many of us in television,” Howard writes,“are simply unaware of the bright mosaic and the swift flow of electronic material passing before our senses. And that the medium itself is other than natural photograph and natural sound.”21 The broadcast television image, typically mediated seamlessly by the camera, is so seductive, its representational powers so convincing, that it blinds viewers and producers alike to the structural basis and logic of the video as a medium. A tiny point of matter, so small one can measure but not fathom its size, races across the screen’s 256 lines at a speed so fast as to be imperceptible, and miraculously appears as a single, coherent, stable image. The viewer might be aware of the fact that there is never a complete image on the screen (as there is in a film), but she can perceive neither the true, partial image nor the electron’s movement. Acknowledging its existence is a matter of logic and of faith. The unity of the photographic image disguises these underlying, material facts. “Until we confront this reality,” Howard argues “those of use who pass so many hours either sending or receiving the moving photographs will care very little whether the cameras are electronic or not. When we realize the immensity of the proposition, however, we may all begin to make ready for a new and inviting possibility.”22

NCET Intern Program Flyer, 1969. Xerox handbill. © KQED. Collection of the Pacific Film Archive. Photo courtesy of KQED and the Pacific Film Archive.

For Howard and the artists at NCET, the new and inviting possibility was not only an open-ended experimental formalist investigation of television that would lay bare its abstract origins, but also a remaking of television, for artists and viewers alike, as an experience of process rather than a consumption of products. The Rockefeller foundation funds insured that Howard’s artists could produce work without the pressure of making popular—or even airable—programs. The foundation’s mandate was for artistic experimentation, not commercial viability or general interest. Unlike the average TV producer, Howard was free to produce tapes that would never air with no financial loss to the station or network. Airing the programs was an added bonus rather than a necessary outcome. Nevertheless, transmitting this experience to viewers fulfilled an important part of NCET’s agenda for changing the public’s idea of what television was and could be. As “A Visit to the Center” demonstrates, NCET’s mission was to show video as a procedural medium, by detailing the means by which an electronic image is continually formed and reformed. The essential nature of video image, then, was one that was continually coming into being through electronic processing. The video image was not a document of capturing, recording and transmitting a camera-based version of reality. Rather, Howard describes it as a responsive and unfolding act of making that happened in real time.

Thus, the NCET programs that did air provoked the viewer to see television images in a new way. She could no longer passively consume narrative images but instead had to see through the image to the screen’s electronic mosaic. Just like the video makers at the center, the viewers, too, had to “go with the process.” The electronic circuitry of the television image, Howard mused, connects everyone in a “giant nervous system being touched and stimulated by each other’s memories, by each other’s probes toward meaning.”23 The NCET projects sought to prepare viewers for this experience of distinctly electronic imagery. Often elaborate narrations and introductions established that the programs were experimental art, at times displaying the SMPTE color bars so that viewers could adjust their televisions to see the work as the artist intended. The video experiments were sometimes paired with jazz or interspersed modern dance to provide both the connection to improvisational forms of art and to provide continuity for the viewer faced with radical abstraction. The viewer had to actively engage with the videospace image and recognize its difference from standard television. The abstract, psychedelic programming that aired in the late evenings between 1968 and 1975 would (re)educate and empower the at-home viewer by delivering videos that laid bare the material structure of the television screen. Despite these efforts, perplexed viewers called into NCET claiming that the station had broken their televisions and even that the video had “given them brain cancer.”24 While NCET’s formalist investigations worked to situate video neatly into the critical discourse of the history of art, educational effects of the broadcasts are harder to ascertain. But even when understood as “breaking” the television, rather than as intentional, educational restructurings of viewer expectations and broadcasting conventions, NCET’s programs signaled to the audience that other ways of making and receiving television lurked just beneath the surface of the screen.

Howard intended Videospace to be both a philosophical treatise on the artistic potentials of television, and a training manual for the center’s intern program, which introduced young artists and engineers to video’s radical potential. The book makes the formalist goals of the center clear. Between the pages of text that encourage an investigation of the base material conditions of television are reproductions of both abstract paintings and circuit diagrams. The aesthetic basis of the video image would be found in the structure of its circuitry. Through this pictorial analogy, Howard places abstraction, the grid, and a rigorous logic of form and structure at the heart of the video, and he maps his desires for television on to the art historical narrative of abstract painting. Both had to follow a path of abstraction and narrative reduction to find their essential forms. Television, however, was not essentially a “painterly” medium or a subgenre of painting. At root it was a multimedia form, both visual and aural, and always dynamic, responsive, and improvisational. While Howard does align his agenda with Greenberg’s via a discussion of the unique and essential forms of the medium and sustained analogies to a formalist trajectory in painting, he simultaneously exposes television as a medium whose specificity is, by nature, multi-modal and multi-sensory. The artists Howard invited to join him at NCET reflect his intuition that video’s medium specificity would be found in multi-media, collaborative practice.

Joanne Kyger, Descartes, 1968. Video stills. © Joanne Kyger. Collection of the Pacific Film Archive. Video stills courtesy of Joanne Kyger and the Pacific Film Archive.

Experiments in Psychedelic Formalism

Two artists working at NCET illustrated Howard’s vision of electronic formalism particularly well: Joanne Kyger and Stephen Beck. Both were working at NCET during its earliest years and broadcast works that mapped psychological awareness on to the formal materiality of the video screen.

While in residence at NCET, Beat poet Kyger made her only video work, Descartes. The eleven-minute, black-and-white tape, completed in 1968 and aired on Friday, November 8, is a video-visualization of her poem “Descartes and the Splendor of. A Real Drama of Everyday Life. In Six Parts.”25 The poem, later published in her 1970 collection, Places to Go, is a contemporary reworking of René Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy. In the 1641 treatise, the French philosopher sets out to prove both the existence of God and of the human soul. The premise of the text is that the philosopher has locked himself in his apartment for six nights to try systematically to understand what is. His musings on each of these fictional nights forms a “meditation.” Following a rigorous program of methodological doubt, Descartes’s six meditations lead him away from the deceptive realm of the senses and the physical world, and toward the internal workings of his own mind.

Kyger’s Descartes, too, has six parts, each forming a meditation on mediated existence. But rather than locating this investigation in the physical world of objects, and then retreating inward to the mind, as Descartes does, Kyger’s video turns the viewer’s attention toward the metaphysics of the screen, transferring Descartes’s epistemological doubt in the senses to the illusionistic, deceiving, representational image of the TV screen.

Descartes opens on an image of Kyger. Her figure, truncated into a bust, floats in the center of a black field. The image shimmers, dissolving into bands and stripes before being quickly doubled, as if reflected in a pool. The kinetic flickering motion at first appears to be a problem with the set’s vertical hold, which makes visible the striped structure of the screen. But the distortion is quite purposeful. It destabilizes the visible body as the origin and container of the voiceover soundtrack of Kyger reading the poem; she becomes merely an image rather than a thing. The video image, like one’s grasp of the world in general, is not stable or sure. In her narration, Kyger states her Cartesian project: “I will delineate my life as if in a picture / so that I may describe the way in which I have / endeavored to conduct my own design and thoughts / in six parts.” Like Descartes, she “resolved to make [her] own self an object of study.” By separating the visible world from her thinking body, she also separates the camera from its strict representational duties. Like the thinking mind, the video image becomes detached from the realm of things. Kyger’s stolid face grows to fill the entire screen and begins to dissolve. It pulls apart at the edges, forming quick moving vapor trails of electronic imagery and then exploding into an extended corridor of visual feedback. While the successive images of her face are stacked, small on top of large, they seem to recede backwards into the deep fictional space of the television screen.

Representational scenes appear between Kyger’s visual meditations on distorting and manipulating the image. The artist appears on a sitcom-style set where she cleans, smokes, makes tea, and acts out the “sweeping” away everything in her mind that might cause her some Cartesian doubt. These moments of pictorial and narrative clarity remind the viewer of how she normally grasps the world and video images—through illusions of wholeness and unstable empirical existence. If her project is to consider herself as an image, “to delineate her life as in a picture,” then the origin of all things in the video is not “Mother God,” as it is in the poem, but the pulse of electronic information. Kyger waves her arms and her body falls to pieces, breaking into dots and bits of electronic feedback that scatter across the raster of the screen. The very stuff that makes up her image and the televisual world—the electron, the raster, the grid—becomes visible. Behind the material, coherent, recognizable structure of her body is not thought, but light. By repeatedly disturbing her own image by allowing the camera to slip into its abstract, self-critical reflexivity, Kyger rends video free from its representational and narrative guises. Video reveals itself as an effect of the camera’s relationship to the screen, rather than the camera’s relationship to an exterior world in general, or the artist’s narcissistic body, in particular.

Stephen Beck, a young electrical engineer, invented an early analog video synthesizer (Video Synthesis Instrument Number Zero, 1969) when he was still an undergraduate at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. In 1970 he packed up his equipment, transferred to the University of California, Berkeley, and became an artist-in-residence at NCET. There he went on to create two other synthesizers, The Beck Direct Video Synthesizer (1970–72), and a digital synthesizer, The Video Weaver (1973). Unlike the other artists working with abstract feedback at NCET, Beck invented devices that allowed him to bypass the camera and its conventional mirroring effects to invest his work specifically in the formal elements of the screen and pure electronic signal and feedback. With his synthesizers, Beck could create video images that had no relationship to the external, visible world, and then feed that image back into the system’s loop. According to Beck, feedback is the television in a “self-meditative state. Input focused on output, its eye focused on its vision.”26 Beck’s video works for NCET extend Kyger’s psychological and psychedelic formalism by eliminating the representational and human elements of the system.

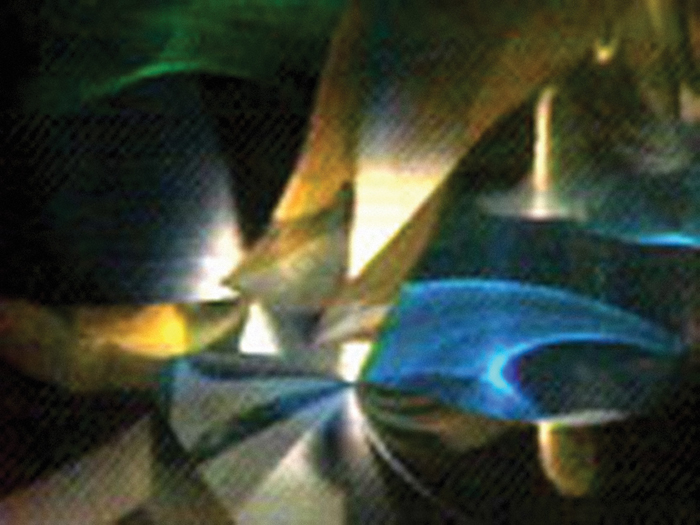

Beck’s synthesizer videos Illuminated Music 2 and Illuminated Music 3, collaborations with composer Warner Jepson, first aired on November 6, 1973. They made up the very first installment of NCET’s series “The Videospace Electronic Notebooks,” a showcase of work made at the center. The broadcast introduces the collaborators, carefully framing what will follow as an experimental artwork. The camera pans across the NCET studio. Beck and Jepson sit at their consoles, hands busy on knobs amid tangles of patch cords and rubberized wires. The announcer analogizes Beck’s unfamiliar machine with the somewhat more familiar Buchla audio synthesizer, which also is an instrument that needs no input other than the electronic signals it produces. As the announcer explains, “It alone generates the forms, textures, and colors you will see, and needs no camera.” The description and the title of the pieces that follow, Illuminated Music, link the video synthesizer to synesthesia, comparing the immaterial origins of its forms to the colorful and mysterious mental images that have no direct origin in the phenomenal, existential world.

The brief introduction, intended to prepare the viewer and to help her appreciate the strange images that will follow, gives way to the performance. A glowing white dot appears on the black monitor. It doubles and then doubles again. The small bits of light skate across the screen, meet, and merge in the center. The dance repeats again and again, each time becoming more complex. The third time around the dots glide in figure-eight patterns around their partners leaving electronic vapor trails of feedback in their paths. The trails lead back to the center point of the screen. Each segment of the trail becomes its own independent dot and the screen becomes a visual field of highly organized static. The shimmering field of light re-condenses into fixed points and the process begins again. The trembling static quickly takes on recognizable shapes—spirals, circles, diamonds, rings, cylinders, mandalas. The shapes move between two- and three-dimensionality: flat graphic shapes change color and shift into subtle shading and shadow, becoming apparently tangible forms before dissolving again into their composite static.

If Kyger’s tape exposes the Cartesian doubt that can (or should) underlie one’s understanding of video images, which appear to be stable images of the world but are merely ungraspable, fleeting points of light, Beck’s work with the synthesizer fully separates video from its representational function so that it can be diagramed in its essence without the distraction of figuration, recognition or narration. His synthesizer performances remap the viewer’s understanding of what a video image is. The Illuminated Music tapes show forms coming into and out of being. While Beck cannot slow down the pulsing electron beam of the CRT so that it might become visible to the viewer, he can show that the video screen is a fluid abstract medium that can give rise to a limitless set of forms, all composed from discrete dots of light. By eliminating the camera’s reproductive images of the external world, Beck makes the formal structure of the screen readily apparent: it is a field of static from which any image might arise. It needs no camera, no connection to the world of objects or to the artist’s body.

Stephen Beck, Illuminated Music series 1-6, 1972–73. Video stills. Images courtesy of Stephen Beck. ©1972–2012 Stephen Beck. All Rights Reserved. www.stevebeck.tv.

Stephen Beck playing the Beck Direct Video Synthesizer live on KQED-TV for the first performance of Illuminated Music I, May 19, 1972. Image courtesy Stephen Beck. ©1972–2012 Stephen Beck. All Rights Reserved. www.stevebeck.tv.

The “True Shape” of Television

The psychedelic, abstract patterns and shifting color fields created and developed by Beck, Kyger, and the other “tool-based” early video makers were endemic to the medium (still only about six years old at the time) because they were essential to it, in the strictest formal sense. Krauss and Pincus-Witten saw video’s nature as grounded in camera-based, representational images and time-based narratives. By investing in the strictly representational (if sometimes distorting) qualities of the video camera, Pincus-Witten and Krauss did not recognize how feedback patterns produced by pointing a camera at its own monitor, and other such strategic explorations such as the NCET projects described above, proposed a self-aware, critical reflexivity rather than a narcissistic reflection. Addressing Pincus-Witten, among others, at the Open Circuits conference, experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton described the structural power of video feedback: “Things find their true shapes most readily when they look at themselves…let video contemplate itself, and it produces, under endless guises not identical avatars of its two-dimensional ‘container’ [as film does], but rather exquisitely specific variations upon its own most typical content.… The feedback mandala confirms the covert circularity, the centripetal nature, of the video image….”27

Under Howard’s direction, the NCET video artists authored an early and nearly forgotten history of video art that, while rooted in the conservative aesthetic agendas of Greenbergian formalism, proposed a radical counter narrative to the performance-based video work that would take critical center stage a few years later.

As Modernist painters had previously indicated to the innate qualities of their medium, the NCET artists “pointed at the center” of the video screen to expose its inherent traits and structures. In doing so, they uncovered a formal logic that separated it from all other media and even from the representational effects of the camera. The specifically electronic properties of video, those that separated it from film and from the established “fine arts,” came to the fore as the flat, gridded, and ceaselessly kinetic surface took precedence over the illusionistic images it had the power to contain and transmit. Looking closely at these tapes, some of the first made by artists, in the context of self-reflexive Modernist logic not only exposes and defines video as a medium, but also shifts the critical reading of the NCET artists’ work and early video in general. Moreover, this experiment in distortionist, psychedelic video did not happen in the gallery or on a closed-circuit feed, but on the air, proposing not just what video could be, but what TV could be as well.

Kris Paulsen is Assistant Professor, Department of History of Art and Program in Film Studies, The Ohio State University.

Note: I’d like to sincerely thank Steve Seid and the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, Stephen Beck, and KQED for their assistance in researching this article, acquiring images, and for filling in the little details.