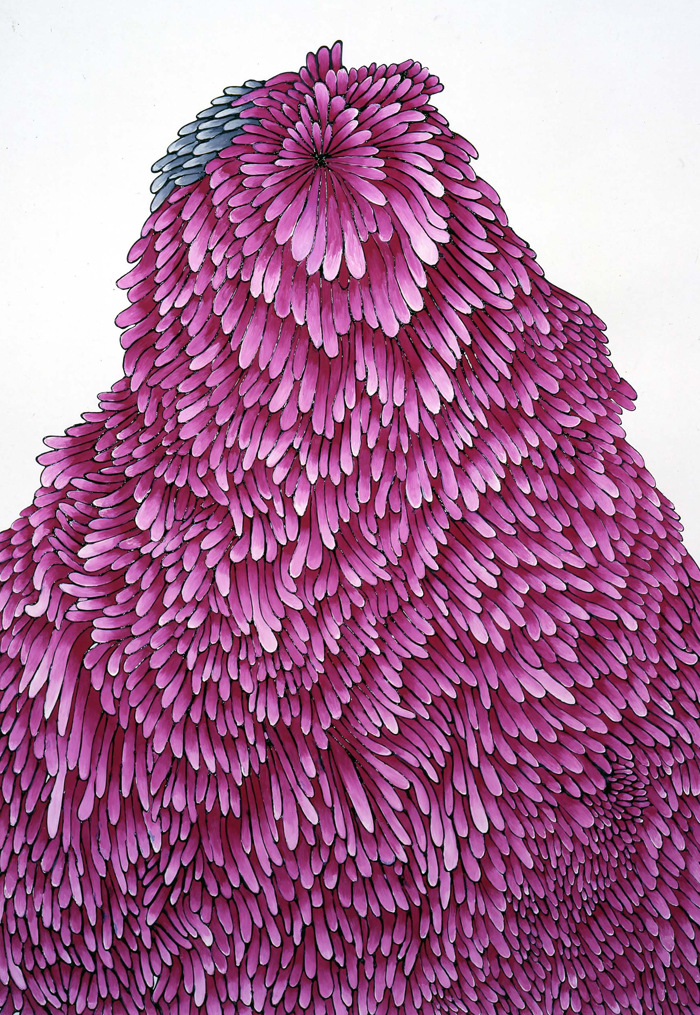

I first encountered Mindy Shapero’s works in the context of emerging LA art at the UCLA Hammer’s Thing exhibition in 2005, where her organically shaped, breezily-textured, richly colorful lump of a sculpture, Orb (2003) was an eye catcher. Soft-shaped and fleshy, it was Surrealism reinvented, evoking, but not representing, a plump torso hiding under an attractive layer of scales made from cut paper. It looked very simple and playful– just a thing – but was obsessively built, complicated, alluring, and a bit intimidating at the same time.

Since her graduation from University of Southern California in 2003, Shapero has amassed an impressive list of exhibitions both collective and solo. The present exhibition at Anna Helwing Gallery is entitled Inside the circletraps (in a zombie state walking around in tight circles from looking too deep into the blinded by the light; some get out and some don’t.), in reference to the ‘zine she offers to complement the show. Her second solo outing features paintings as well as sculptures, the former hanging on the walls at eye-level, the latter placed on the floor as if they were growing out of it. The paintings depict metallic, shiny, hollow faces that let out a numb scream through open mouths. The sculptures, as Shapero writes in a leaflet accompanying the show, both “come from the drawings and become three-dimensional drawings.”

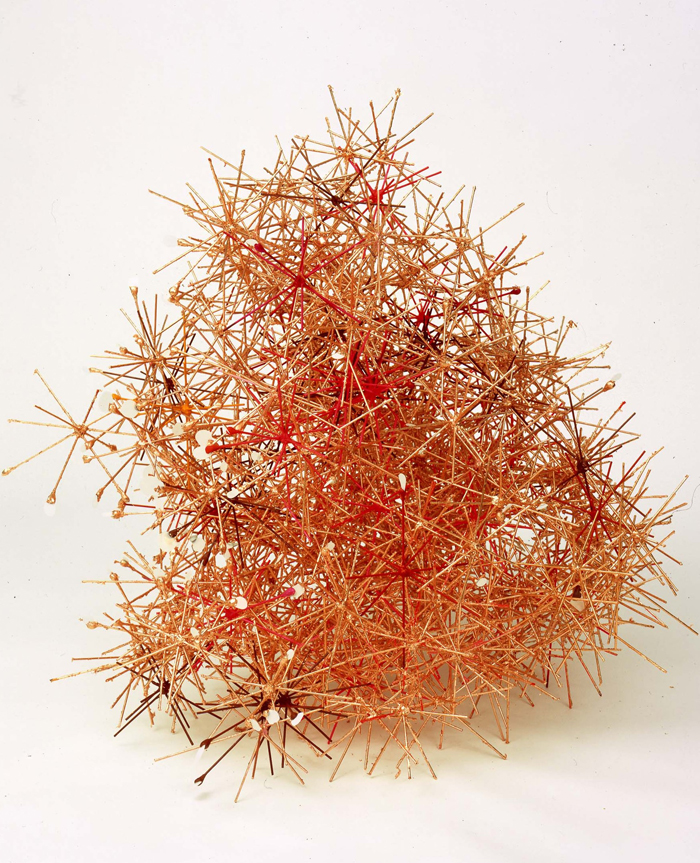

Seductive and threatening at the same time, Mindy Shapero’s works make a strong visual and visceral impression. Most are built of tiny particles that add up to suggestive sculptural fantasies. Whether body-like or transparent structures, they strike one as systems of incessant, unstoppable, compulsive growth from the inside out. A richly colored, twisting, snake-like form enters a muff of sorts, which looks soft and hairy covered with layers of black paper blossoms; thorny structures are growing into space. In another work two open-mouthed faces stare at each other from under thick layers of colorful or striped scales. Shapero’s usage of concentric circles, rainbow colors, and dense layering drive the viewer into strange territory where the palpable presence of something hidden lingers.

Her objects can be read both as benign play and monstrosity. On the one hand, the crowds of little blossoms and the random shapes they form are blithely exuberant. The sense of growth they evoke is also satisfying to the viewer: more is better. Taking many small things, such as thousands of colorful little paper pieces, and making something big out of them is a truly rewarding experience that harkens back to childhood: you work with little elements to achieve something beyond your own dimensions. On the other hand, the whole process of building and growing can get out of hand. In a Sorcerer’s Apprentice fashion, what start out as loving constructions can morph into scary overgrown creatures and there is no stopping them. Because Shapero’s imagery is vaguely biological, it can exude as much discomfort as coziness. Layers of scales begin to appear as if they multiply like cancerous cells, whence their beauty doubles as a dark joke or menace.

Shapero walks the thin line between spelling out existential angst and playing it down, or, more exactly, dressing it up in visually intriguing forms and colors. Her actual subject is the perplexity of what is hidden and dangerous, which she veils with fascinating textures. Nothingness, threatening to trap and engulf the living, is shrouded by organic growth, which, as it were, turns out to be complicit in disguising the void by making it appear attractive.

The process by which she creates intimacy is authentic and genuinely childlike. It leads back to familiar early fantasies and nightmares. “The mind which plunges into Surrealism relives with glowing excitement the best part of its childhood,” André Breton said in 1924, because it is in childhood that everything “conspires to bring about the effective, risk-free possession of oneself.”1 ‘Risk-free’ might be the key phrase to describe Shapero’s longings while she is inventing a universe of high risks and threats. Her titles sound like hastily whispered childhood secrets: Yellow and copper Ghosthead guide that will bring you to the Ghosthead god, you can only visualize the guidewhenyouhaveenteredtheMonsterhead, and first you have to be serene enough to be able to even see the Monsterheads before you can wear one (2005-06). Such charming confessions are more elaborate, for example, than Yves Tanguy’s alarming 1927 title Mama! Papa is wounded! but function similarly by adding an epic dimension to the visual.

Shapero’s present-day epic is a self-invented version of the classic fairy tale that bespeaks and relieves anxiety. It is also about fear of monstrosity and our own potential to engender it. Her narrative starts out with a cute little patch of fur that has always been around, sitting “like anthrax does in the middle of a place seldom traveled by humans or animals,” when suddenly it becomes activated. Driven by a yearning to be loved, it steals the eyes of everyone in a village, and, discovering that “these eyes could advance its progression and growth,” engulfs even more eyes. Learning to see with eyes that it has stolen enables it to steal even more eyes. Growing to the size of a large sack, it becomes like King Ubu, the fantastical character imagined by French teenager Alfred Jarry more than a century ago who would later become a fixation in Surrealist practice. Although Shapero’s sack threatens to engulf everything in the world, ceding to the economy of fairy tales its very growth is ultimately turned against it. Once it becomes visible and threatening, people protect themselves.

Shapero’s archetypal story of the all-devouring thing is a transparent combination of the unconscious as it manifests in fairy tales with early French Dada/Surrealist farce and our chilling present-day anthrax-anxiety. The motif of fur recalls Meret Oppenheim’s 1936 Fur Tea Cup. Its usage in Shapero’s convoluted story is similarly sexually charged, alluding to the hidden parts of the body and conveying the horror of becoming as well as the loss or lack of one’s control over the process. A talisman invoked to protect one from the monster may in fact cause more harm than defense: “Little did they know that they created another monster,” Shapero says, hinting at the potentially endless repetition of monster-breeding. Following the dream-logic of Surrealism, Shapero finds a way out of the vicious circle: escape is made possible via a regimen of relaxation and meditation in order to achieve a state when, as she puts it in the ‘zine, “all sound becomes visual and silent.” Importantly, in this state “everything slows down.” To bring this mythology full circle, she introduces Circletrap Monsterheads — empty shells that lead out of the trap those who have found peace.

Shapero also presented another work in the exhibit that operated outside of the above narrative. Called The reversible time changer, upside down and inside out, explaining the rules of the infinite truths of the world, hardly translatable (2005), this compact object shaped like an irregular piece of marble streaked with veins of color stands on four pegs, each planted in the center of a system of painted concentric circles. In this artwork, her desire to reverse time reveals, once again, the straightforwardly childlike fantasy of magically retrieving what has been lost. A spellbinding gem in psychedelic shapes and colors, it could serve an illustration to a story of Borges, whose “temporal twisting” Shapero refers to as an important influence on her work. Its endlessly repetitive circles also suggest it can be an object of meditation.

During the 1960s the usage of psychedelic colors presented a formula for illustrating newfound freedom, drug experimentation, and a general breaking loose from the norms and rules of society. While efforts to fathom the unknown implied revolt half a century ago, over time the basis for such pursuits has been challenged. In Shapero’s works, a hallucinatory palette stands in for mystery rather than making the expected anti-establishment statement. Through dizzying concentric circles and visionary colors she extends perception, glimpses magic, and pursues insight. Like Alice in Wonderland, Shapero is bound to explore multi-dimensional realities, gaping holes and inside-out time behind the looking-glass, scripting the adventure as it is happening.

Éva Forgács is a critic, art historian, and curator living in Los Angeles. She teaches at Art Center College of Design.