Among the many vanities of the self-conscious condition we call Modernity, perhaps the most contested one is the notion that identity as it once existed is no longer possible. Theorists, artists, and philosophers have variously proclaimed identity as an untenable social and psychological construction whose sole purpose was to contain the overflow of human differences into controllable meanings. For women, minorities, and outsiders of many kinds, this proposition has been both enticing and problematic. To rid oneself of the contingencies of an identity might indeed be liberating, while on the other hand availing oneself of its mechanism also has fueled many of the liberation movements, from the nationalism of the nineteenth century to the gender, ethnic and sexual identities of the twentieth century. For feminist artists, the social dynamism of the women’s liberation from the mid-sixties to the mid-seventies not only brought about changes in what women could do, but in how women might think of themselves.

Seeking to displace the notion that Cindy Sherman invented the idea of role-playing in contemporary art in the 1980s, curator Jori Finkel assembles a rich show of earlier feminist work on identity and gender roles. Eleanor Antin’s widely seen work with several characters throughout the seventies is placed beside Lynn Hershman’s four-year inhabitation of her alter ego, Roberta Breitmore, and the far less known photomontage work of American-Canadian artist Suzy Lake. The periods of these works, 1972-1978, coincide with the end of the Vietnam War, the collapse of the Nixon Administration, the mainlining of women’s liberation, and the gradual absorption of sixties values into mainstream culture. There’s a sweetness, a sort of nostalgia in this work, and like much of the feminist work seen this year in Los Angles, it reminds us how little real progress has been made in gender politics.

Eleanor Antin, Portrait of the King, 1972. Silver gelatin photograph, mounted on board, 13 3/4 x 9 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

The very idea that gender was a role, which one might accept or reject, propelled a generation of artists toward work that does neither or work that plays with social roles. Antin, Hershman and Lake seek less to find their identity in their work of the seventies than to experiment with other identities, as though becoming other might be the most direct route for a woman artist entering the art world.

Among the several axes along which this exhibition is deployed is that of the ordinary versus the exceptional. While typological, few of the roles that Eleanor Antin chooses for her characters are ordinary. The King first appears in the 1972 as a peripatetic performance Antin staged throughout the streets, fields and businesses of Solana Beach in San Diego County. He came to Antin as she was experimenting with gluing whiskers to her face, and in her full beard she recognized her resemblance to Anthony Van Dyke’s portrait of Charles I, beheaded in 1649. “We were very much alike,” Antin says. “He was a stubborn hopeless romantic like me. He was a political loser like me.”

Antin seems less concerned with being a man than with being a King, with both his privileges and obligations. He is an idealized male self, reminiscent of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, but with a broader sense of irony. He is seen hitchhiking, waiting on lines in the bank, buying groceries, but also greeting his subjects in Solana Beach, California. A certain kind of noblesse oblige characterizes his postures and misadventures, but he is more Quixote than Henry VIII; while he tries to organize the youth and the elderly subjects of Solana Beach into a resistance against its booming real estate development, he fails. The tragicomic gesture also characterizes Antin’s two other famous characters–the nurse and Antinova, the black ballerina. At points, Antin has characterized these three as Jungian archetypes, but what separates them from Jung is their postmodern insouciance or buoyancy: they are more surface and symbol than traditionally psychological characters.

The ballerina represents Antin’s “idealized female self,” an aesthete, an avant-garde expatriate who dedicates herself to art and artists but whose life is punctuated by failures and misunderstandings. Even her glamorous publicity photographs are achieved by use of wooden props on which to balance her limbs, later inked out of the images. Antinova, narrated here by pages from her autobiography just as the King is revealed in the fanciful ramblings of his journal, springs forth as a great narcissist: a would-be Isadora Duncan whose desire to become a great artist is often foiled by her love and admiration of the great male artists and geniuses of her time. Both idealized and idealistic, Antinova’s “darkness” is also a code for her Jewishness, partially hidden here behind the ethnic mystique of being black, American, and Native American–everything but European. She is impossibly seduced by Europe nonetheless, yearning for its radical, idealistic politics and an avant-garde that fuses aesthetics and politics and refuses to separate one’s life from one’s art.

Eleanor Antin, The Nurse and the Hijackers (installation view), 1977. Video installation: cardboard paper dolls, airplane chairs, cockpit, and cabin dividers, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. Photo credit: David Guilburt.

The nurse begins as a 19th century European but is then recast as a modern American. In her first incarnation she’s a doppelgänger of Florence Nightingale, the saintly, altruistic 19th century founder of nursing, and in her second a modern nurse whose fast-lane soap opera life is almost redeemed when she saves a hijacked jet and nearly alters Middle-Eastern politics. She’s a helper, not a narcissist. She aids and organizes, using her good sense and caretaking capacities to better the world. The highlight of Identity Theft is an installation of Antin’s cardboard set and paper dolls for her 1977 video, The Nurse and the Hijackers. As in its counterpart, The Adventures of a Nurse (1978), the nurse is a kind of puppet master who narrates episodes from the nurse’s life using handmade cardboard dolls and her own voice for all the characters. Both videos are included in the show. Adventures is a hospital melodrama of love, seduction, sex and betrayal, in which the nurse suffers both the death of her beloved patient, a poet, and the Machiavellian seduction of the chief doctor. In The Hijackers, the nurse enters the world of oil politics, religion, revolution and international terrorism. Throwing off melodrama for hard political realities, the nurse negotiates with Arab hijackers and tries to understand their intense, life or death political commitments, so far removed from her own world. She is an ordinary woman with an extraordinary life.

Eleanor Antin, The Nurse and the Hijackers (detail), 1977. Video installation: cardboard paper dolls, airplane chairs, cockpit, and cabin dividers, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. Photo credit: David Guilburt.

Antin’s king, ballerina and nurse are less identities she assumes than allegorical characters she builds through intricate, spirited narratives–an empowerment of girls dressing up and telling stories. They allow Antin to interrogate the history of art and popular culture, the trajectory of European culture into American values, and the political legacy of colonialism, capitalism and the avant-garde. These are in the forefront, but the operations of the narrative move slyly through the lens of gender, a woman artist inserting herself into the ironic center of a discourse which in its own way is not to be mastered.

It is worth noting that a younger friend of Antin’s, Kathy Acker, launched her literary career in San Francisco a year after Antin began working with her performance characters. Re-inventing herself as the Black Tarantula, Acker self-published her first novel in 1973 as a piece of mail art, six installations mailed to the address list from Antin’s just-completed mail art project, 100 Boots. Acker’s Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by the Black Tarantula was published under her assumed name, and the writer cultivated her mystique by among other things having her phone number listed as the Black Tarantula and appearing at public events dressed only in black. Much darker than the work in this show, Acker’s persona is the bad girl to these artists’ essentially good girls, closest in a way to Antinova, who lives only for herself and her art.

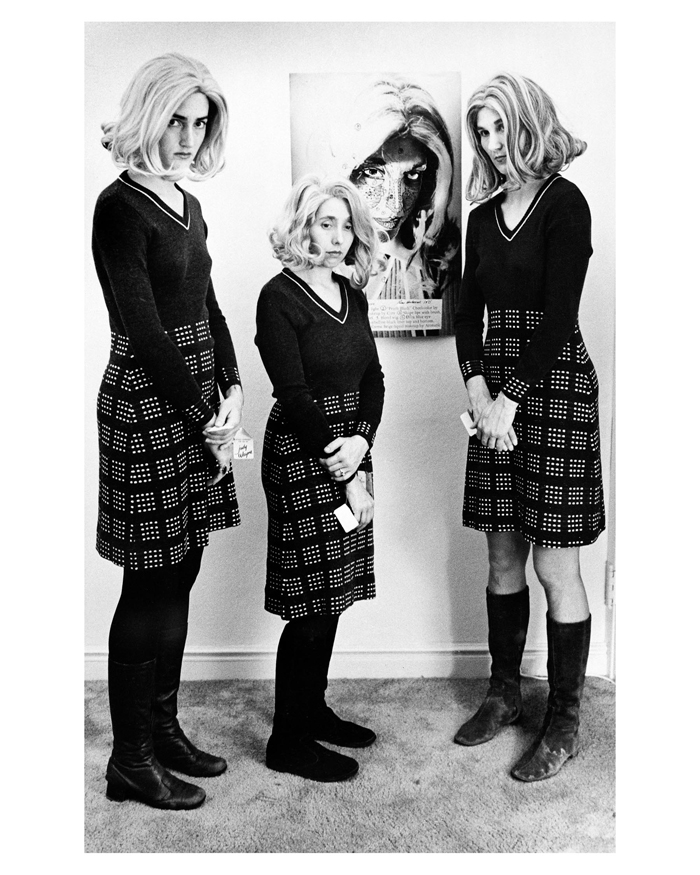

A year later in the same city, Lynn Hershman began her extended performance as Roberta Breitmore. While the Black Tarantula was a pirate and a killer, Roberta Breitmore is a kind of generic Gal Friday, an uncertain young woman who moves to the city to find herself. Her name echoes Marjorie Morningstar and Sylvia Scarlet, two great heroines from ’30s films, but she isn’t “more bright” in the way that they are colorful and energized. Breitmore is Hershman’s counterpart, a regular person, not an artist, a little lost and depressed, looking for a life. Her face looks like a mask because it is mask: Hershman in a blond wig and makeup, often behind sunglasses. Hershman gave Breitmore a set of familiar anxious gestures and her own loopy handwriting. Breitmore took out personal ads and her meetings with two men are documented here with surveillance-style images. Her correspondence with potential lovers and roommates is painstakingly displayed in vitrines, embarrassing somehow in its guilelessness.

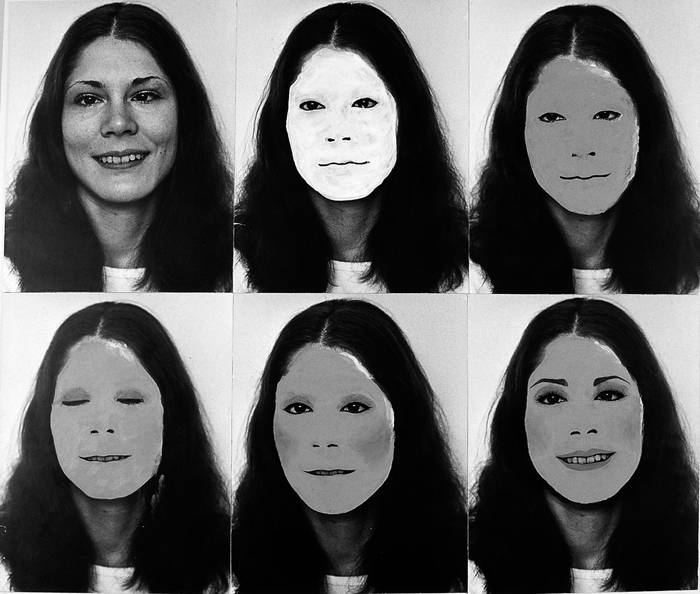

Lynn Hershman, Roberta Construction Chart #1, 1975. Chromogenic photograph of handpainted photograph, 38 5/8 inches x 45 7/8 inches x 1 3/4 inches. Courtesy the Hess Collection; Napa, California and Berne, Switzerland. Photo credit: David Guilburt.

Breitmore is a blank, a cipher who stands in for the masses of women outside the ’70s feminist movement but haunted by many of its issues without knowing it. She is depressed and visits a psychiatrist, whose evaluation of her is framed in the show along with the handwriting sample (an excerpt from her journal) he has requested. She cannot comprehend her disconnect from the world, and the photographs of her, whether in close up, medium distance or long shot, reflect a mask without a body, a person in search of an identity. Her depression worsens and she contemplates suicide. She joins Weight Watchers and despite her effort ends up gaining weight. Her doubles begin to appear everywhere; they are called Roberta Multiples.

Roberta’s relation to the multiples is uncertain. Are they duplicates of her, other aspects of herself, or usurpers taking her identity? The answer can be found, perhaps, in the last of the Breitmore series–Roberta’s exorcism in Italy performed, it seems, not on Hershman but on a multiple. After four years of possession, it appears as if Hershman needed to rid herself of her melancholic other. The most poignant part of Hershman’s work is the many artifacts clinically displayed under glass: Roberta’s sunglasses, her purse, checkbook, diary and driver’s license, a sample of her blood and her urine, her blond wig. A missing button from one of her jackets, which is also on display, is tinged with melancholy. Who collected these artifacts? Hershman, of course. But while Breitmore is a cipher, Hershman is even more so, the ghost behind the character. Where is the artist, and who is she?

Lynn Hershman, Roberta Multiples Gather at de Young Exhibition in front of Construction Chart (left to right: Michelle Larson, Helen Dannenberg, and unidentified Roberta impersonator), 1978. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/4 x 9 1/4 x 1 3/8 inches framed. Courtesy the Hess Collection, Napa, California and Berne, Switzerland.

What lies behind these questions is a subtle commentary on the invisibility of women in the art world, a proposition that the only way a woman artist could enter it would be through the creation of a “her” as a subject of the work. Later in the project, the Roberta Multiples start to appear at galleries and art openings, documented again by a series of surveillance-style photographs. The key here is the Multiples contemplating an earlier image, Roberta’s Construction Chart #1, a diagrammatic examination of Roberta’s face. In the layering of selves and self-images in the gallery context lies a commentary on women as objects of representation versus women as selves.

Roberta’s Construction Chart #1, is part of a group of handpainted photographs entitled Roberta Searches Her Soul. The only “aesthetic” work in this group, these photographs, adorned with watercolor brushstrokes, makeup or magic marker, are more lyrical though also more analytical than anything else in the Breitmore project. In them the artist contemplates the self, Roberta’s face, both revealing and obscuring her features. But who is the artist? Does Roberta have artistic ambitions or is it Lynn Hershman? Probably both and neither. By examining Roberta’s representational status and absenting herself, Hershman keeps a disciplined focus on her questions of self, identity, interiority and the performance of social roles. Hershman says that Roberta was both a “black hole” who sucked in everything around her, and “a mirror held up to the culture around her.” Like Antin’s work, Hershman’s project resists autobiography to hew more closely to issues of the gendered self and its construction.

Suzy Lake’s primarily photographic project is more conventionally image-based, but its importance lies in its prescience, the way in which it anticipates Cindy Sherman’s much lauded photographic impersonations made almost a decade later. From Detroit but working primarily in Montreal, Lake’s work has never been seen to this extent in the United States; her legacy is one of much influence but little recognition.

The core of her work here is three (of eight original) Transformations. With a negative of herself posed similarly to three friends, two of them male, Lake creates series of transformational large-scale black and white images of herself incorporating facial features of her friends. These are placed above prints of the friends with markings over the features she has adapted. Done before the advent of Photoshop, Lake employed two negatives, double exposures and multiple stencils. Each image is 36 x 30 inches, and the groupings of six or ten images dominate their space, anticipating the large-scale photographic portraiture in the decades to follow.

One must see Lake’s photographs through eyes of the time, a woman adopting the facial features of her male and female friends, including glasses and varied facial hair. Lake sees these as tributes to people who influenced her, raising the question of the nature of influence on identity, as well as pondering to what extent we are all a collage of everyone who has mattered to us. The images are confrontational but also strangely mute, perhaps less a statement than an inquiry into who we are to be looking at her, questioning both the nature of identity and the gaze. Perhaps because Sherman’s images are so familiar to us–so closely do they cleave to the archetypal film stills they imitate–they have lost their capacity to unsettle us in the same way. Because Sherman’s work has become such a familiar trope, the relative muteness and almost naive quality of Lake’s photomontages require attentiveness in order not to be misread through her renowned successor’s lens. (Sherman included one of Lake’s Transformations images in an exhibition she co-curated at Hallwalls in Buffalo in 1975, leading the viewer to speculate on Lake’s potential influence on one the most prominent feminist artists of the 1980s.) Rather than work in the studio with lights, set, makeup and costumes, Lake’s self-examinations take place in the darkroom. In this she interrogates photography as much as the nature of identity.

Suzy Lake, A Genuine Simulation of…No. 2, 1974. Six silver gelatin photographs with covergirl eye shadow, eyebrow pencil, eyeliner, rouge and lipstick, framed as one piece, 29 3/4 inches x 34 5/8 inches framed. Courtesy the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, purchase, Saidye and Samuel Bronfman Collection of Canadian Art. Photo: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The use of the photomontage in the European avant-garde gets subtly domesticated here, and its relocation in North America makes it more subtle and less explicitly political. It is hard to interpret the meaning of Lake’s photographs: Are gender and individuality permeable or does their commingling here demonstrate how resistant each force is in identity formation? The obvious conclusion, that all identities are constructions, seems partly true, but just as powerfully Lake’s images resist closure, as if to imply that identity is procedural and not subject to arrest. Unlike Antin and Hershman, the location of identity in Lake’s work is almost purely on the face and the body. It is inhabited almost passively, rather than performed with the vigor of Antin’s characters or the ambivalence of Hershman’s Roberta Breitmore. It is also a double erasure, of both Lake and her subject, so that the very features that constitute identity flow from one to the other. One becomes the other, and not without a certain monstrosity.

Like the ordinary and the exceptional, another axis here is the mask of identity as opposed to the performance of identity. These photographs rely on image rather than narrative, on the text of the face. A Genuine Simulation of…No. 2 is a collection of six photographs of Lake’s face with increasing hand-colored modifications using Covergirl eye shadow, eyebrow pencil, eyeliner, rouge and lipstick. This seems less a critique of makeup in favor of some essential true face than a commentary on the layers of self; under every layer lies another. Identity is truly false. As do her two colleagues, Lake questions the status of photography as a truth-telling form, and instead positions it as part of the armament of identity construction and truth formation. Placed on a line, Antin, whose characters all do something, occupies one end; Hershman is in the middle, and Lake, whose self-character is a canvas or a screen, is located on the other end.

What links these three artists is the sense that in order to escape identity, we invent identities, multiplying ourselves. The women who made this work are all present in it but also absent, and perhaps this is more than just a reflection of how untenable gender was becoming in this period. This absent presence is also the ambiguous presence of women artists in an art world coming out of a decade of conceptualism and relative abstraction into one of the most highly politicized postwar eras. Nothing here is confessional or even declarative, not even confrontational, but still the work asserts itself, asking the viewer to think rather than telling her what it means.

Becoming other was perhaps the most powerful entry into the art world of its time, a strategy used by generations of modernist male artists, such as Marcel Duchamp in Rrose Selavy, the 1921 Man Ray photograph of Duchamp in drag. These projects are not quite as camp, or flagrant, but they exude subtle ironies. In the works of the mostly male conceptual artists so influenced by Duchamp who precede Antin, Hershman and Lake, the ordinary had already become absolute, the thing in itself. But here the ordinary, with its relation to the domestic and thus feminine notions of attractiveness, is a field for interrogating the gendered self. All three of these women distance themselves from conceptual abstraction, but it is the ordinary that they use to fuel their drive for recognition, the ambition to be seen as extraordinary which is taken to be so natural for men.

Matias Viegener is a writer who lives in Los Angeles and teaches at CalArts.