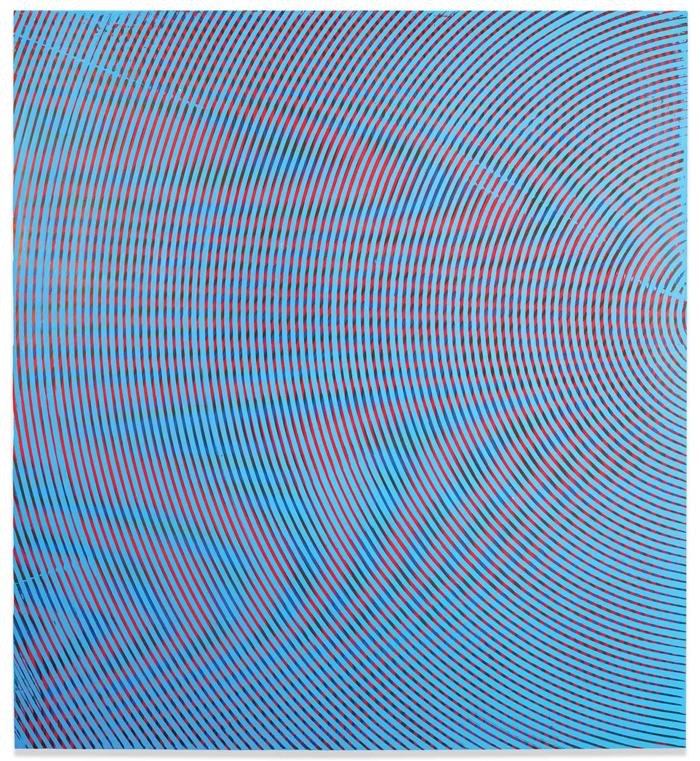

Anoka Faruqee, 2012P-46, 2012. Acrylic on linen on panel, 22½ × 20½ inches.

Liena Vayzman: Your new series of paintings based on moiré patterns is insistently optical, yet making the paintings requires a sustained and physical process, one prone to unpredictability. What does physicality look like for you as a painter?

Anoka Faruqee: Physicality exists in the work, but at a remove. I rake thick wet paint with custom-made notched trowels, like raking sand in a Zen garden. Then I sand down the dry surface. Slips of the hand, drips, uneven pressure on the tools, the paint itself being too thick or too thin in places, these are all key elements. Sanding it down, these slips are reduced to a flattened and graphic image that is the trace of a physical process.

LV: Historians of Op art often regard opticality and physicality as opposites, as if the emphasis on optical illusion needed to mute the physicality of paint as a material.

AF: I want to be an optical painter who affirms the physical in a way that Bridget Riley or Victor Vasarely did not. This physicality comes not just from the materiality of the paint, but also from my intersection with it, from the physical actions of my body in making the gestural pull with the trowel. These physicalities differentiate my paintings from Op art, from magic eye, screensavers, codegenerated fractal patterns. I am seduced by these things—but once I see the trick or the algorithm perform once or twice, I get bored, like eating too much candy. So my work needs to unravel in the moment to stay alive.

LV: The human touch, the tactile qualities of paint application and removal—and the mistakes that happen in that process—inflect your paintings away from something that a machine can make.

AF: A machine, or an overly diligent human, maybe? I don’t want to associate perfection with machines and failure with humans. In my work, the body is trying to be machinelike, but not succeeding. I aim for perfection in order to fail.

LV: The moiré effect, a visual interference resulting from the overlay of two or more patterns in printing or imaging, marks a failure of the machine.

AF: Moiré patterns are a common and unwanted effect of digital and print imagery: when the pixelation or banding in printing misregisters, moirés result. I find them to be beautiful and unpredictable, which is why I’ve been spending much of this year figuring out how to paint them. I create moirés by layering patterns; this superimposition produces an image that is more complex and quite unlike any of the underlying patterns.

LV: The question becomes: What is the relation of the part to the whole, and the process to the product? In the first glance at least, I did not realize that they are not simply made all at once. Because the finished surfaces of these new paintings end up ultra smooth, there is a real sense of mystery about how they were made.

AF: Some clues about the process can be found in the finished works, but yes, I realize now that most viewers have no idea how these objects are made. At a certain point, I stopped taping the sides of the painting, in order to reveal the intense ooze of paint dripping from the gestural pulls, in contradiction to the glass smooth surfaces, as a way to let people into the messiness of the process. The peripheries are becoming more and more significant, because I want my paintings to be read, at least partially, as a residue of the performance of painting it.

LV: You bring up performativity as applied to painting, which has to do with being in a body, in a moment in time. This relates to performance art, but I’m thinking more of finished paintings that tell the story of their own making.

AF: A performative painting invites the viewer to mentally reenact the physical, material, and bodily processes of its making. In my early diptychs and triptychs (2000–2006), where I painted copies of my own paintings, the hand-painted asterisks were marked on predetermined grids. Decisions about color and composition were made ahead of time, so assistants could paint the asterisks by following the grid. When the work became more freehand in the fade paintings (from 2006–11), I began making decisions in the process of painting.

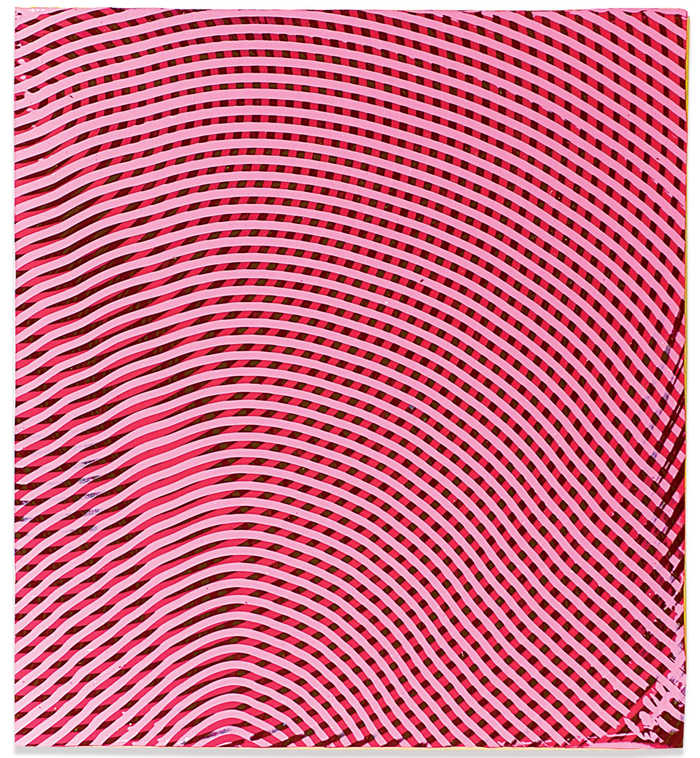

Anoka Faruqee, 2012P-18, 2012. Acrylic on linen on panel, 11¼ × 10¼ inches.

LV: By elongating the shapes as you move across the surface of the canvas, you build the narrative of the painting module by module.

AF: Yes, distorting the size, direction, and shape of each module creates spatial illusions. So then I had to paint everything myself, because those paintings are improvisational, about me creating space with the curves in the moment of painting. These new moiré paintings continue the improvisational aspect through gestural pulls.

LV: We’ve hit upon two themes in your paintings. The first is chance, aleatory processes such as those used by John Cage, and the second is the conceptual decision making of Duchamp and everyone since who follows in a conceptual vein.

AF: What you are talking about is a questioning of subjectivity by using a system, a grid, chance, or accident as “anticompositional” structures. Sol LeWitt wanted to get away from the caprice and arbitrariness of subjectivity, but the systems he used were equally capricious, arbitrary, and subjective.

LV: Still, in painting, there’s an almost mythological connection between the gesture of the hand and authorship.

AF: Peter Halley makes a distinction between painters who build paintings and painters who paint paintings. He put himself in the category of builder and likened himself to a sculptor in that way. I think of painters who build as architects, they do all the design work—and then the execution follows faithfully. Painters who paint make decisions during and through the process of painting. This distinction is related to the contradictions we talked about between the optical and the physical in my work. In all of the moiré paintings, there is some optical plan that is going to be built, yet this plan gets interrupted and augmented as it gets painted.

LV: So are you a builder or a painter?

AF: I was a builder, now I’m a painter. My first major body of work, the diptychs and triptychs, were built. I was critiquing the impossible romanticism of expressionist painting, as was Halley. With the freehand fade paintings, I became a painter. With these moiré paintings, I’ve added a visceral physicality to the process. I’ve accepted the centrality of gesture in painting, because the hand and the body are making conceptual decisions in the moment of the movement of the paint. I am resisting the idea of a fundamental division or distinction between mind and body, idea and movement.

LV: A preconceived optical plan is the modus operandi in both the moiré paintings and the freehand fade paintings, yet you are not simply fulfilling a plan to the letter, since choices inflect the outcome along the way in all your work.

AF: No mark is solely an expressive Pollock mark or a conceptual LeWitt mark. When I heard Sol LeWitt talk, he said that he started out his work to be a critique of mark making as a representation of the artist’s “essence.” He wanted anyone to make his works by following his instructions. But he soon realized that skill, or at least craft, was important, and he had to train and authorize people to make his marks, and many of them became more skilled at making his marks than he was.

LV: I first heard you speak about your mark making in relationship to Buddhist meditation at the Feminist Art Project panel [Artist, Woman, Human, 2012]. In meditation, repetition and seriality are vehicles to cultivate awareness of the present moment.

AF: Recently, I’ve been relating the ideas of Buddhist presence to Roland Barthes’s theories of authorship. In “Death of the Author” [1967], Barthes talks about a rare form, the performative verb, where speech in the first person, present tense, itself fulfills its own action, such as saying, “I apologize.” Speech and action become one and the same thing. In Barthes’s new site of non-authorship, each text comes alive in its making and its reading. Describing this new writing as enunciation, he says: “Every text is eternally rewritten here and now.”

LV: How do you apply this concept to painting? Are your paintings indexes, traces, residues of the performative tense? One of the clear references for me in your earlier fade paintings is breathing, as in paying attention to each breath in meditation. Each module is a breath, and the painting repeats the module over and over, building a world over time. Paying attention to the breath and embodying each one unites mind and body. Each gesture calls your attention in its execution. I also see it in the relation of the part to the whole—each breath or moment metonymically becomes the entire whole: all of the universe, all of time. But in the recent moiré work, the Buddhist influence exists not in the repetition of a module, but in the necessity to be very present in doing the all-atonce trowel pull.

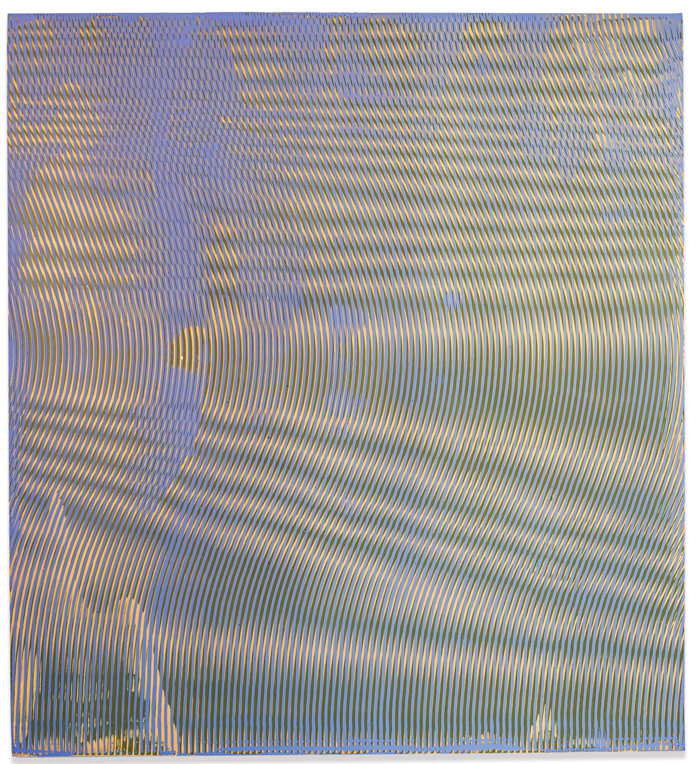

Anoka Faruqee, 2012P-47, 2012. Acrylic on linen on panel, 22½ × 20½ inches.

AF: Yes, exactly. I’m interested in reading more about traditions of Zen painting, and how they bridged control with accident, as a way to talk about mindfulness and acceptance. From what I understand, the preparation through training, repetition, and discipline ultimately makes way for the moment of improvisation. It becomes a way to understand what it means to be in a body in a moment in time.

LV: The last line of a Theodore Roethke poem comes to mind: “I measure time by how a body sways.” In “dematerialized” works, such as conceptual, site-specific and performance art, authorship is removed from the object itself and re-sited within the performativity of the author, thus circling back in the body of the artist. Miwon Kwon calls it the “return of the author,” in her book One Place After Another: Site- Specific Art and Locational Identity [2004]. Your paintings also deal with time.

AF: Painting is one way to make time material or physical, a way to slow down our everyday experience of time, both in the act of making it and in looking at it.

LV: You have spoken about color as being part of pre-planned optical systems, and materiality and gesture as part of a performative process. How do you think about color in perception in relation to this concept of the momentary?

AF: Good question. Color changes so dramatically in context, depending on what’s next to it, or how it’s lit. It’s constantly fluid in perception. I am a huge devotee of Josef Albers. Color is always striving. My work dissects perception, in order to get a fictional hold on it, to lock it down.

LV: But don’t you think color also reads as cultural code?

AF: I did have a painting that I realized was red, white, and blue. I nixed it and changed it to a greenish blue.

LV: It was too patriotic, or too obvious?

AF: I was hoping that the painting would transcend the reference point. But it didn’t.

LV: Certain color combinations are set in people’s minds.

AF: Color is so affecting emotionally, it has been a useful tool for culture to codify it for certain things—like red, white and blue, Christmas colors, or pink as the representation of femininity. Color is both purely phenomenological and iconic in culture. I’ve always thought that these two different ways to read color were at odds with one another. But now I think they function simultaneously. Culture assigns a color to stand for patriotism or femininity, it’s naturalized and internalized in an unconscious way, and that’s why it sticks.

LV: Naturalizing color to trigger emotive reaction is also tied to capitalism’s reliance on consumerism as the engine. So we have marketing to women: a whole pink ribbon campaign, with pink standing for a woman’s issue. Pink of course also codes for homosexuality; the pink triangle was used to persecute gays, and then it was reclaimed by queer activism. Its meaning shifted. Color is not natural, it is cultural!

AF: Yes, but it’s also phenomenological. I love pink, actually. Unlike red, white, and blue, or Christmas, that’s the one that I feel like I can own.

LV: You can own pink?

AF: I’m not afraid to own pink! And now, in thinking about it, there are good reasons I don’t feel I can own U.S.A. or Christmas. So, yes, I’m always trying to make the colors interact with one another in the moment so that they become something else, so that they don’t stay in one easy place. My paintings both affirm pink’s association with femininity and divorce it at the same time.

LV: How does our discussion of the cultural and phenomenological aspects of color relate to shades of skin tones and discussions about people of color and racism in this country? What do you think about the term “person of color,” for instance?

AF: I don’t address the issues of skin color directly, though I have written about how Byron Kim and Glenn Ligon have dealt with the intersection of identity, skin tone, and monochrome painting. For me as a painter, though, the more pertinent issue is seeing color as cultural. My parents emigrated from Bangladesh and we would go back to visit every other year. I remember flying back to the United States on one such trip, getting delayed, and spending the night in New York. I helped translate for a young Bangladeshi woman, a stranger, who had never left her country before. I remember looking at her in JFK, and she had the most intense mustard sweater on. It was the dead of winter: everything around her was black and grey, the airport decor, the other passengers’ clothing, the landscape through the window. She looked outside and asked me what types of tree these were, trees that had no leaves. The color saturation of her sweater was so striking, and it was a metaphor for her being out of place.

LV: Color, then, is in part geographically determined, and relates to your identity as an author.

AF: If you go to South Asia, to India, to Bangladesh, walls will be painted a bright turquoise color. There is no holding back, no fear of saturation. In Bangladesh, the word “gaudy” is a compliment. Women are competing to have the gaudiest sari. My parents decorated their house with rugs and wallpaper. It was full of color and patterns of all kinds, including the psychedelic patterns of the ’70s that had been influenced by South Asia.

LV: In the West there is both skepticism about color and a simultaneous attraction to its perceived decadence and superficiality.

AF: That is something I’ve always been interested in: reaffirming the place of color in painting—fighting the chromophobic impulse. I’ve had a similar feeling about the decorative. Color has always been associated with the decorative, as has pattern, and I hope my work undoes some of these binaries: superficial vs. deep, decorative vs. conceptual, rigor vs. pleasure, etc.

LV: We started out speaking of material and bodily accidents, imperfections that assert the unpredictability of your process and challenge your authority and authorship. Yet your role as an author, your cultural background and biography, have clearly entered the work as well.

AF: You are yourself. But making art both affirms and challenges your origins and your biases.

LV: What is the relation of the present tense performative verb paint, and the finished painting as object? Isn’t there a contradiction?

AF: This contradiction is at the heart of my work. We’ve spoken about the present tense and the momentary, and the connections with chance procedures and dematerialized artworks. Yet I’m giving my viewers finished, seamless, sometimes impenetrable objects! Still, these paintings are a trace or residue of a bodily, material, and momentary act, and I hope they come alive again and again, as a viewer questions and wonders about what he or she is looking at and how it came to be. For me, a painting is finished when it asserts a presence that I can only describe as the right balance of discipline and unruliness, when its structure unravels in the act of looking. That balance might make enough perfection for you to see an enigmatic illusion, and enough imperfection to make it open, approachable and complex: real and material, human.

Anoka Faruqee is a painter who lives and works in New Haven, CT. She has exhibited her work in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, and in Asia. Group and solo exhibitions include Max Protetch, Monya Rowe, Thomas Erben Galleries and Hosfelt Gallery (New York), PS1 Museum (Queens), Albright-Knox Gallery (Buffalo), Angles Gallery (Los Angeles), Chicago Cultural Center, and June Lee (Seoul, Korea). She received her MFA from Tyler School of Art in 1997 and her BA from Yale University in 1994. She attended the Whitney Independent Study Program, the Skowhegan School of Art, and the PS1 National Studio Program. Grants include the Pollock Krasner Foundation and Artadia. Faruqee is curently an associate professor at the Yale School of Art, where she is also acting director of graduate studies of the Painting and Printmaking Department. She has also taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and CalArts, where she was co-director of the Art Program for a number of years.

Liena Vayzman is an art historian, curator, and photographer. Recent publications include “Feminist Film Noir: Sally Potter’s Thriller Unpacks Misogyny” for Dirty Looks: Queer Experimental Film and Video (New York) and “Farm Fresh Art: Food, Art, Politics, and the Blossoming of Social Practice” in Art Practical (San Francisco). In 2012, she curated the Crystal Palace: 1st ArtSpace Experimental Film and Video Festival, based in New Haven, CT, and traveling internationally.