Kim Dingle, The Lost Supper (general maintenance), 2006. Oil on mylar, fifteen panels; 90 x 72 in. (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

The French word précaire indicates a socioeconomic insecurity that is not as evident in the English term precarious; indeed, précarité is used to describe the condition of a vast number of laborers in neoliberal capitalism for whom employment (let alone health care, insurance, or pension) is anything but guaranteed.

—Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency

There are two alarms in Los Angeles: short, pulsating screeches for an earthquake and long hoots for a fire. I have never heard the former—a blessing that verges on pathology, a hanging fruit gone overly ripe. Over time, the threat of disaster constitutes the disaster itself. It’s been 25 years since the San Andreas Fault’s last major movement, a 6.7 on the Richter scale that hit the San Fernando Valley in the middle of the night in 1994. My childhood home, they told me, smelled like barbecue sauce. Like notches on a ruler, or a bedpost, periods of time lacerate themselves against the Californian. One precarious metronome often births another: like the sound of a skateboard on a sidewalk, a year without another earthquake shoves the Angeleno into the ever-greater probability of the next Big One. I hear a skater go by outside, dreading the misstep. Ka-dunk, ka-dunk. He stops, and my temporal matrix lurches.

My dreams have gotten worse since I started hostessing at a literally “high-end” restaurant downtown—the one at the top of the tallest building in Los Angeles. If you’re from a fault line, you know the ritual: What building would you least like to be in when it happens? We know how to look above us for power lines, telephone poles, eucalyptus trees. Recently, I have begun to feel like working at the 1,000-foot-high restaurant is akin to being inside God’s Jenga. The collapse, be it mental or physical, is unquestionably imminent—if not already upon us. One night in my sleep, a party of eight showed up unannounced. In another, my manager asked me, what are you thinking?, and I stared back blankly, unable to tell him that my legs had turned into a sludge the color and weight of our mushroom entrée. Working in a restaurant is to live on the edge of emergency, a breed of which no one can understand until they’ve walked in a large circle for six hours handling the requests of the gluten-free. Or, more realistically, working in a restaurant is to live inside a disaster of both personal and political proportions—a disaster that has happened, is happening, and will continue to happen. Artist and former restaurant owner Kim Dingle captures something of the deep end of precarity: the service industry.

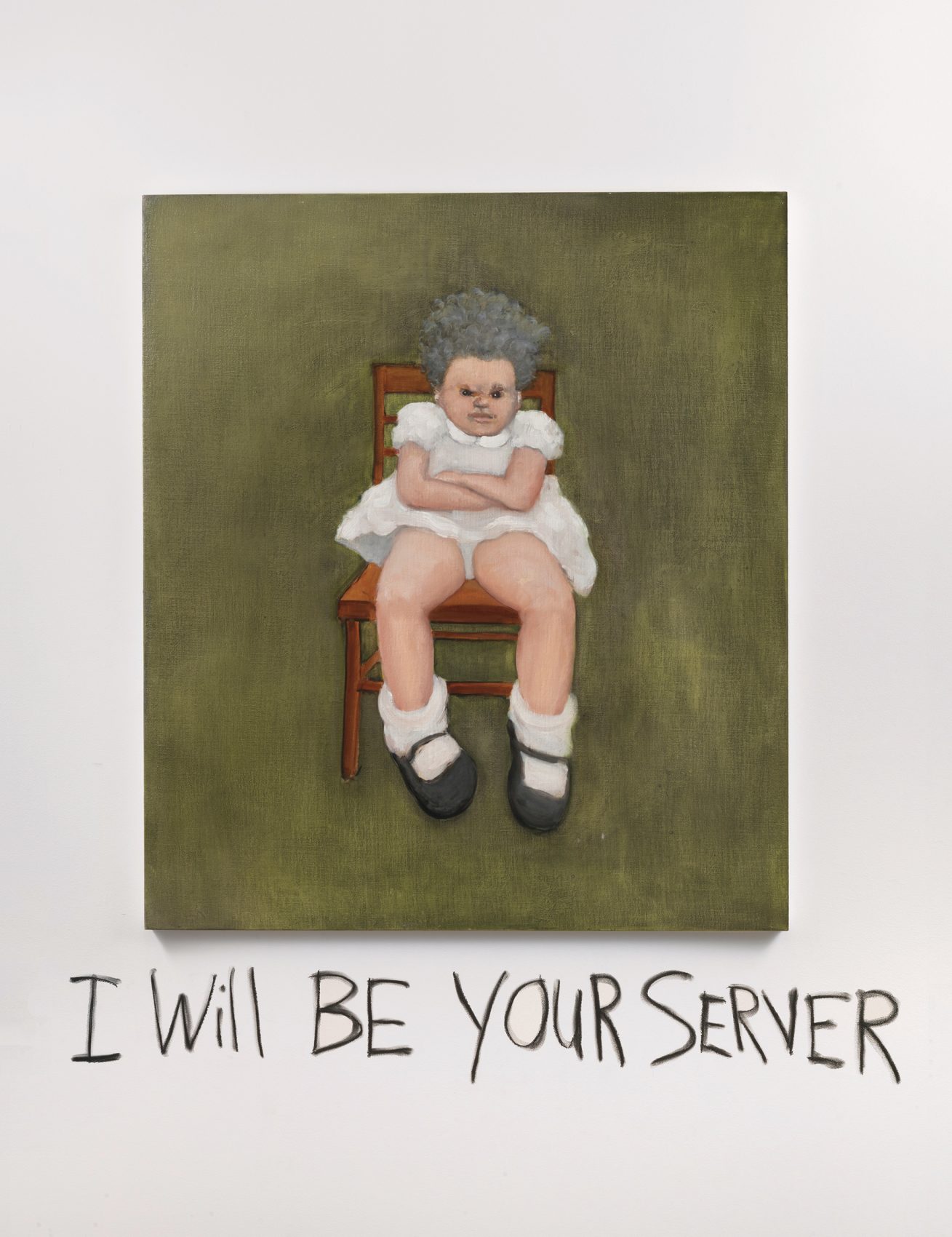

I Will Be Your Server (The Lost Supper Paintings), installation view, Vielmetter Los Angeles, Culver City, California, March 2-May 4, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Dingle’s 2019 show at Vielmetter Los Angeles, I Will Be Your Server (The Lost Supper Paintings), is an extension of an earlier undertaking that began while Dingle was still running a restaurant called Fatty’s in Eagle Rock—the establishment closed its doors in 2013. She began producing work inspired by the “urgency, drama, and brutal stress of Fine Dining” for a 2007 show, Studies for the Last Supper at Fatty’s, at New York gal- lery Sperone Westwater.1 Dingle weaves a captivating web around the origin of the paintings at Vielmetter. The work, she says, was “lost” after being stored in pizza boxes following the close of the restaurant. (The large-scale paintings are comprised of smaller squares of vellum seemingly taped together, each square roughly the size of a pizza box.) Over ten years later, Dingle’s paintings were unearthed from storage and put on view. This whimsical narrative sets the tone for the exhibition, which is both Seussian in its playfulness and indicative of the self-compromising onslaught of work in the service sector.

What circumstances led an established artist to “lose” her paintings? The answer may lie in Dingle’s furious depictions of her “fat white-frocked everygirls” in a fancy dining establishment. Whirls of white socks and tumbleweeds of hair fill each canvas as the girls vault between positions as servers and as customers, destroying (and getting destroyed by) everything around them. In Watermelon Martini (2006), girls line up along a dinner table, some in chairs, some falling off of them. Blooming white dresses stand in contrast with the brown skin of some of the girls—it’s a self-consciously diverse group—but many of them are also headless, their faces replaced by more carefully painted green glass bottles and a single pink martini glass. It’s like a bomb went off in a Catholic day school and our truants broke into the Vin Santo. Dingle revels in ambiguity, but not ambivalence—her girls are violent, playful, overwhelmed, servile, cute, and raucous. Though her work’s subject matter lives in a politically rife, underrepresented, and overpopulated corner of the socioeconomic world—the hospitality industry—its message is far from didactic and resists easy summation. Dingle’s girls were raised on the clock and under the whip, and their reactions to the omnipresence of control are satisfying (f*ck you, I’ll do what I want!) while still suggesting a kind of looming, powerful darkness that dictates their every move. Dingle’s young girls play as they work and work as they play, pushing the paintings towards a terrifying and gleeful realization of the précarité of contemporary life.

I Will Be Your Server (The Lost Supper Paintings), installation view, Vielmetter Los Angeles, Culver City, California, March 2-May 4, 2019. Background left: Studies for the Last Supper at Fatty’s (Wine Bar for Children II), 2007. Vellum framed in powder coated welded aluminum, diptych; forty panels total, 77 1/4 x 243 1/2 in. (overall). Background right: Watermelon Martini, 2006. Oil on vellum, sixteen framed panels; 77 1/4 x 96 1/2 x 1 in. (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

One of the paradoxes of Dingle’s work lies in her relation to her subject matter—as a restaurant owner, she is the de facto capitalist, possessing enough surplus to start a business and employ members of the wage-earning class. Writing for Yale’s Post45 on the “painful repetition” of service work, John Macintosh speculates that “those in a position to represent their experience are atypical not only of the restaurant industry, but the service sector as a whole.”2 Surely Dingle occupies this “atypical” category as an artist who, as she says, “accidentally opened a full service restaurant in the middle of my studio in Eagle Rock.”3 Dingle’s small operation demanded of her a plethora of tasks that would normally fall to non-stake-holding employees: the artist says she was responsible for “wine and janitorial.”4 Small business owners like Dingle take financial risks in order to get their establishments off the ground—a kind of risk that strictly binary assumptions of capitalist v. proletarian often fail to acknowledge.5 Dingle’s young girls offer a similarly loaded ambiguity; they are both privileged, messy customers and waitresses driven to the brink. Her figures are anti-work and anti-play, compelled by an un-fun desire for workaday destruction. While Dingle remains a member of an exclusive class of individuals who can employ others, she still manages to capture much of the truth of restaurant work. Her efforts to evoke the mania of the hospitality industry through anarchic female toddlers suggest that waitress, owner, and even customer may be possessed by the same impulse to blow it up, all of it—the time clock and the payroll, the entrée and the appetizer.

Kim Dingle, Table Tipping, 2005. Oil on mylar, fifteen panels total; 90 x 72 in. (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Upon entrance to the gallery, a scowling, gray-haired girl peers down at the viewer (I WILL BE YOUR SERVER, 2005). The titular phrase is scrawled in a ghoulish, horror-movie typeface directly on the wall. The text is an inextricable (and presumably un-monetizable) part of the show: it cloaks the gallery, a shrouded declaration that infuses every work in the exhibition. The gray-haired “server,” complete with Dingle’s characteristic white frock, matching visible underpants, and black Mary Janes, replicates and dissipates across the paintings—she never appears again with such clarity. In Studies for the Last Supper at Fatty’s (Wine Bar For Children II) (2005), a crowd of girls sits at a dinner table with their backs to us. Their faces are depicted with strikes of black paint, their dresses gashes of white. It is no longer clear if these girls are indulging or assisting in dinner service: one figure appears to bend over a chair as though to push it in for a guest, while another bearing her same uniform sits propped on a stool, drinking from a martini glass. The girls’ ambiguous actions indicate a comic confusion of play and work, an aesthetic category dubbed the “zany” by critical theorist Sianne Ngai. Typified by characters like Lucy Ricardo of I Love Lucy (1951–57) and Jim Carrey’s role in The Cable Guy (1996), the zany suggests the “exhausting and precarious situation” demanded of workers in post-Fordist capitalism, where “the concomitant casualization and intensification of labor” results in a “paradoxically entertaining failure to be joyful.”6 Dingle’s Wine Bar For Children (also the name of her 2013 exhibition at Coagula Curatorial) turns a space for working adults with dispensable income into one for children. The “casualization” of labor means that working looks a lot like playing, and vice-versa. Yesterday, a friend told me that at IBM the term work/life balance has fallen out of favor. In its place is the almost too-perfect Ngai-ian work/life integration.7 Think team-building exercises, “emailing,” work lunches, and board retreats. Work has transcended the now desirable 9-to-5; we are 24/7, 365. Even the epitome of un-work—the child—finds herself getting a glass of fifteen-dollar Pinot with the girls. In Dingle’s world, everybody needs a drink—even toddlers.

Kim Dingle, The Lost Supper (cherry rickey), 2007. Oil on mylar on panel, nine panels total; 54 x 72 in. (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Ngai’s aesthetic of zaniness refers to a rising archetypal figure in late capitalism as well as a stylistic or formal quality in works of art. If the zany contests “the stability of any formal representation of personhood by defining personhood itself as an unremitting succession of activities,” then Dingle’s furious brushstrokes leave her girl right where she should be: unrealized and caught in the flurry of constant event.8 In Table Tipping (2005), a brown table and glasses are painted starkly, while billows of white, black, and brown are all that remains to suggest our familiar girls. The Lost Supper (cherry rickey) (2007) shows five figures facing the viewer. The exact position of each girl is unclear, as they appear to be in the midst of movement; one figure stands on her chair, her dress flung behind her, while her arm appears to merge with the appendage of the toddler sitting by her side. Their brown hair and skin seem to bleed into the canvas, creating brackish clouds over the dinner table. Dingle’s diverse casting is sometimes unrealistically utopian, conjuring a world where non-white and white girls suffer the exact same punishments for public misbehavior: self-destruction. The roughly hewn, activity-centered paintings emphasize the effects of late capitalist zaniness on every figure at the expense of distinguishing the different (and more fatal) ways service work affects women of color.9 It is as though the near-deadly bacchanal of their workplace/playground—what’s the difference?—has deteriorated the outlines of their faces and bodies, be they what Dingle calls “Van Dyke brown” or “pinky white.”10 Constant work and event seem to overtake and ultimately define each girl, a process that seems to apply not only to Dingle’s characters but also to Dingle herself. The rushed, motion-oriented paintings manifest the movement of the body demanded by restaurant work. Dingle’s brushstrokes imply the artist’s gesticulations as immediately as they evoke the girls she depicts; I can imagine Dingle handing menus to customers or explaining a dish with the same actions she performs with a paintbrush in hand. The loose and frantic brushwork that typifies Dingle’s style is emblematic of a larger condition within contemporary life, where “unremitting activity” is increasingly concomitant to the self.

Kim Dingle, The Lost Supper (janitorials), 2006. Oil on mylar, twelve panels total; 72 x 72 in. (overall). Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

The collapse of personhood under the work-or-play regime persists throughout Dingle’s work, where objects of the restaurant interpolate the girl until she crumples into the easel. On first glance, the paintings appear to be fun, expressive romps through the gardens of consumption—before we realize that whoever led us to our table is near-dead, her face mottled and her dress askew. In Chocolate Batter (2005), a figure pours black liquid out of a large blue bowl that obscures her face and body—all we see are her bare, chubby white legs. Here, objects of food service swell with precision and clarity while the girls are obliterated, their faces flicks of paint on canvas. This is true across the exhibition: bowls, cakes, bottles, and wine glasses are painted starkly when compared to the evocative gestural style used to depict Dingle’s young girls. In the last room of the exhibition, we are greeted with the refuse of a dinner service, girls absent—save one. In The Lost Supper (janitorials) (2006), a girl collapses into a yellow mop bucket, either stuck or too exhausted to move. Soap suds cover her body, their color mingling with the white of her dress. The effect is haunting: as much as we want to dismiss the girls as playful and uninhibited, here she is literally drowning in work, covered in it, becoming it. Yet almost more striking are the paintings where she is absent. Untitled (Dinner Plate) (2005) features three tall stacks of white plates, which appear to extend beyond the canvas in all directions. The painting is surprisingly stark and minimal for Dingle: each plate is confined within its own clear margins, piled neatly on top of another. The Lost Supper (general maintenance) (2006) is messier, showing tubs of frothy water and food-covered plates spilling over the edge of a dish pit and into three trash cans. While the workers are almost absent, the work is not: the seemingly endless clean-up of the dinner implies a staff that does not need to be actually imagined in order to be present. The metonymy is complete: Dingle’s girl is interchangeable with stacks of plates and murky water—her toddler face and body become one oversized blue bowl.

Kim Dingle, Untitled (Dinner Plate), 2005. Oil on canvas, 72 x 60 x 1 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Dingle’s work lets us imagine a skintight precarity that hinges on a type of self-obliteration in an environment defined by constant work, work that increasingly looks like the most desperate, vicious form of play. In psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s 1965 theory of psychosis, the psychotic “breakdown” is defined by “a failure of a defense organization”—the “defense organization” being the formulation of the ego and the self, an organization that is infantile and shapeless in the moment of crisis.11 Looking at The Lost Supper Paintings, Dingle’s girls seem more and more akin to working women who wear their girlishness like a mask, compelled into childhood by a hospitality mandated of dinner guests and waitresses alike. Dingle’s dangerous girls are always women, already women—women because they work, not in spite of it. Their occupation of a myriad of roles—server, janitor, drinker, eater—suggests the collapse of any environment free of what is demanded by the workplace. Dingle’s paintings show us Winnicottian psychosis in brackets, figuring the restaurant as a place that reduces adults to an “infantile and unformed” state.12 Her infants are made to work like adults—to “happy-hour” like adults—and in turn her presumably legal employees act out infancy for the tipping populace. In this way Dingle shows us, finally, that precarity is democratic in its subjection: nobody is left unscathed. In fact, nobody is even left alive.

John Macintosh argues that repetition is the quality of service work that makes it so hard—even boring—to render, leading to a strange dearth of imagery for an experience so common to the young American worker. He proposes “service as a holding pattern,” a place cordoned off from the world, outside of which life happens.13 He’s right. Dingle’s paintings feel, sometimes, strangely niche. The exhibition at Vielmetter mimics the plot of a three-course dinner: we meet the girls (appetizer), we see their violence (entrée), and we see its effects (dessert). The consequence of this is to leave the gallery with the notion that the story has ended, fin. Perhaps this is Dingle’s lavish cruelty: to imagine service work as a pattern that withholds the promise of a future to its participants. This is what makes precarity so unspeakably difficult to represent: it is life lived in the cul-de-sac of meaning, propelled by the mandates of living (joy, work, children, food) but without the security and stability necessary for flourishing. It’s also what makes Dingle’s work so fascinating; paradoxically fun and fatal, her paintings evoke girlish frivolity while imagining genuine brutality and total anarchic destruction. If words like precarity imply a level of balance or on-the-edge suffering, Dingle’s work explores the real world of precarity that is already a disaster—disaster in the everyday, disaster in the how can I help you and the have a good night. Say thank you, I remind myself as a party of four gets into the elevator. I say it, and then I say it again. The “animated suspension” of a working life is experienced as a genre of mounting emergency and, in Dingle’s paintings, it is depicted as such.14 The Lost Supper Paintings are a nightmarish trip down reality lane.

Claudia Ross is a hostess from the San Fernando Valley.