Within the second Chicago Architecture Biennial, the exhibition Vertical City revisits the venerable 1922 design competition for the Chicago Tribune Company headquarters. The exhibition is part of the overarching theme of “Make New History” put forward by the biennial curators—Los Angeles architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee. Fifteen towers by 15 architects and firms, including Ensamble Studio, of Madrid and Cambridge, Massachusetts; Basel’s Christ & Gantenbein; and Berlin-based Kuehn Malvezzi, form a gauntlet of model skyscrapers in the Sidney R. Yates Gallery of the Chicago Cultural Center. Each posits a contemporary response to one of the 1922 competitors. The goal of the competition, almost 100 hundred years ago, was to design “the world’s most beautiful office building,”1 and at the time, the publishing and display of the original 263 proposals for Tribune Tower operated much like its own biennial. While the New York architects John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood won with their Gothic Revival beacon, which still stands four blocks up the street from the Cultural Center, Viennese architect Adolf Loos’s gigantic Doric column and Germany’s Ludwig Hilberseimer’s no-nonsense rabbit-eared framework have exerted the greatest influence on architectural discourse today.2 Indeed, models of both appear here, and they bookend the fifteen new and imposing, half-inch-to-a-foot-scale proposals. Didactics on the wall portray a selection of the original 1922 renderings alongside statements of intent by the Vertical City participants. The model towers, each around 16 feet tall, stand tightly clustered in rows like colonnades. One approaches the works at eye-level, then cranes one’s neck up, like a tourist walking through the Chicago Loop.

Vertical City, installation view, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017–January 7, 2018. © Hall Merrick Photographers. Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial and Steve Hall.

The collected models are sketched notions, not resolutions offered for urgent specifics. Because each puts forth an imagined program for a fictional vertical space, the proposals invite viewers to engage through narrative. For example, Other Histories, by London-based Serie Architects, a proposal for the Tribune’s “Far East Asian Headquarters,” is filled with brightly colored tables, chairs, and benches straight out of a miniature Design Within Reach showroom. Looking at Serie’s stacked white pavilions, the viewer envisions the productive activity—breakout sessions, pitch meetings, Skype calls with advertising sponsors, content aggregation, and coffee breaks (mini treadmills are included too)—that might take place within this “tower for a media [conglomerate] with global reach and capital based off-shore,”3 as the firm’s statement describes it, that could be anywhere or nowhere, detached from everything but its readership.

New York’s MOS describes its entry, & Another (Chicago Tribune Tower), as “a ghostly figment.”4 One can picture the underpaid and over-caffeinated Tribune staffer within watching the light at dusk coming through its translucent walls with a sense of foreboding. Surely at night the icy whole of the stacked glass monolith would appear like the gleaming citadel of a comic book villain’s headquarters. Mexico City-based PRODUCTORA’s Two Towers appear as twin gridded volumes of MDF framing densely covered with red and blue cross-hatching, a reference to co-founding architect Carlos Bedoya’s sketches from a previous competition. This viewer wonders, who in the office had the onerous job of coloring the 16-foot model with a ballpoint pen?

Undercurrents of alienated labor swell in Ensamble Studio’s Big Bang Tower: A Column of Columns for the Chicago Tribune. In its statement, the studio observes: “In our contemporary culture working spaces can no longer be understood as the fixed cubicles where the worker spends the entirety of her day immersed in her own particular task, progressively accumulating piles of paper that will require ample amounts of physical storage. A shift of paradigm is happening, enabled by information technologies, that opens new avenues to reimagine the meaning of space.”5 Steel framing studs around the exterior of Big Bang Tower relegate core infrastructural systems, like plumbing stacks and elevators, to the outside of the skyscraper. This move allows the opening up of variable floor plans at different levels. Visually, and paradoxically, the building becomes a sleek and airy cage for the worker described within.

Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, (Not) Another Tower, 2017. Installation view, Vertical City, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017–January 7, 2018. © Tom Harris. Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial.

(Not) Another Tower, by Tatiana Bilbao Estudio of Mexico City, is the one model that targets a specific social concern: the luxury residential high-rises sprouting across the globe, which make up the majority of towers being built today. In her statement, Bilbao observes, “As buildings tower upwards the social fabric of a community is stretched thinner, effectively enclosing people within vertical suburbs.”6 These towers stand detached from the city and encourage alarmingly isolationist tendencies within. Bilbao instead tries to envisage a diverse skyscraper “neighborhood.” (Not) Another Tower is subdivided into 192 different “plots” that are then each designed differently with “fourteen collaborating neighbors,” mimicking the Tetris-like amalgamations that produce cities in the first place.

In her statement, Bilbao poses the important question: “How can space be manipulated and connected [by architects, builders, or residents] to create truly vertical communities?”7 Each parcel in the model contains its own design language—smooth white archways here, angled wood beams there—and hints at the lives to be lived inside. The final result is a pillar of dioramas clinging to a central framework that ruminates on an often-unrealized potential for a complex and layered urbanity within a typology of space that originates and generally endures as a monument to business.8

Interestingly, in the inaugural Chicago Architectural Biennial of 2015, Tatiana Bilbao presented, in this same room, a full-scale prototype responding to housing shortages in Mexico.9 Made of painted concrete blocks and wooden pallets and adaptable to different conditions, the split, pitched-roof house could be built for around $8,000 in its simplest formation. Since then, 3,000 of the houses have been built in the Mexican state of Coahuila.10 Bilbao’s move from a tangible solution to a thought-experiment in 2017 is indicative of a curatorial shift away from crucial applicability and toward navel gazing. As a whole, the models in Vertical City offer formalist meditations on the “tower type.”11 One can add narration to their design elements or note their references to architectural history, but they will never fill a corner of Chicago. They offer choose-your-own-adventure stories within the binding of the historical Tribune Tower competition, not involvement with the complex social world of the built environment.

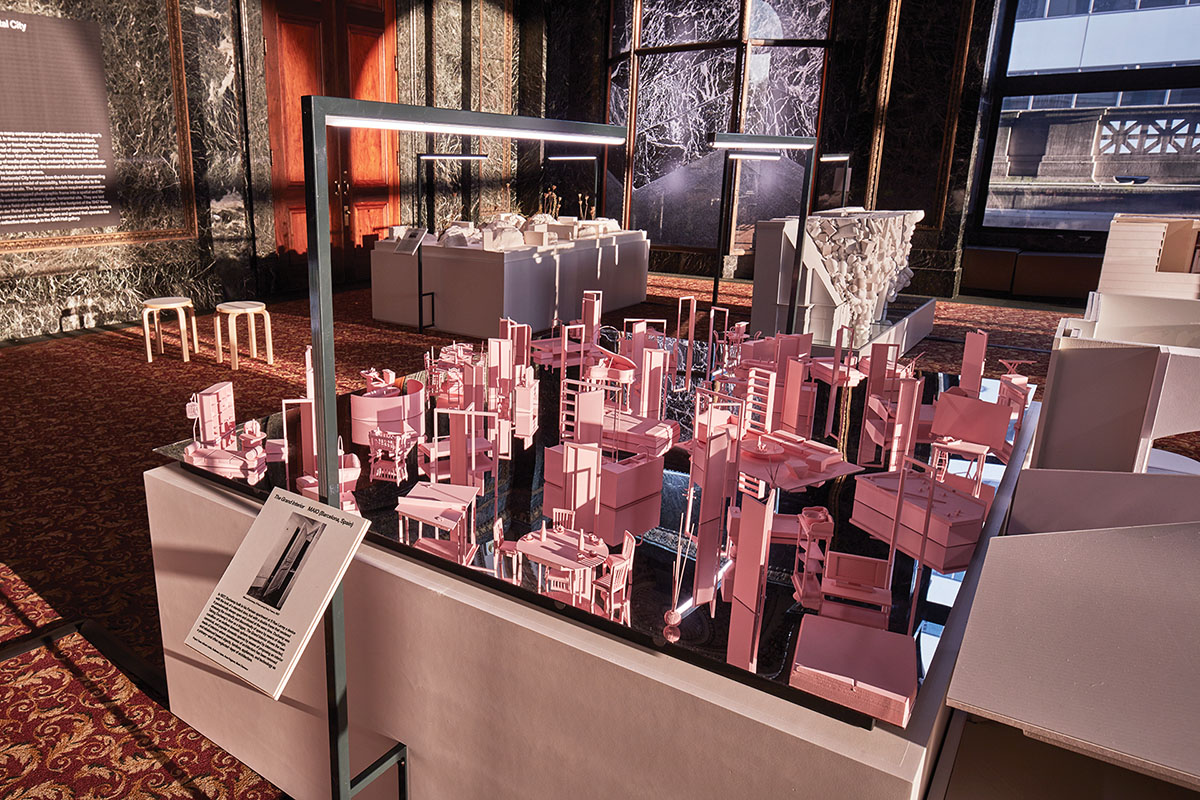

MAIO, The Grand Interior (model), 2017. Installation view, Horizontal City, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017–January 7, 2018. © Tom Harris. Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Chicago’s problems—whether one experiences them firsthand or via Chicago Tribune articles—are spatial problems. A headline such as “8 people shot in Chicago over 24 hours, including man killed by police on South Side,”12 an article from the November 30, 2017, edition of the Tribune, can be diagrammed to reveal decades’ worth of the city’s planning and design manifesting as housing segregation, ghettoization, militant policing, gang culture, cyclical urban renewal, and now rising rents alongside population loss. Moving from Vertical City to Horizontal City—the biennial’s companion exhibition of models riffing on historic images of architectural interiors—only pulls visitors further from the Chicago context and into esoteric fantasy spaces. In its “interior made of interiors,”13 MAIO of Barcelona stockpiles miniature pink sofas, chairs, shelves, tables, and beds atop a mirror that reflects the ornate ceiling of the Cultural Center’s Grand Army of the Republic Hall, in response to a photograph of a door swinging between two frames that Marcel Duchamp once had installed in his Paris apartment. The New York/Berlin firm June14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff invites one to step up to a mirrored bar setting and into Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergére (1862). Viewers are invited to play the imaginary roles of either the female bartender or the top-hatted man soliciting her in that famed painting, and experience Manet’s use of the mirror to define interior space. All 24 such musings are presented on plinths laid out in the original footprint of Mies van der Rohe’s plan for the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). This curatorial conceit visually unifies the scattered works in Horizontal City within the easy reference to one of Chicago’s greatest hits of architectural landmarks, and a specifically horizontal one.

A gigantic white model of the entirety of the IIT campus and the surrounding Bronzeville area stands just outside the Republic Hall. The model, made by IIT College of Architecture students working with Tokyo’s SANAA, is one of a few works in the biennial that reference a real Chicago neighborhood. The objective of the project was to visualize a way to connect the campus to Lake Michigan via the addition of new “mountain-like buildings”14 in the blocks between. The mountains of rubble recently made of Chicago’s past, particularly by the demolition of housing projects such as the Robert Taylor Homes—which stood just south of IIT—are unintended references.

In this context, the biennial’s Make New History signage—inspired by the 2009 Ed Ruscha book of the same name, which contains 624 blank pages15 —begins to feel like a cousin of the “Building a New Chicago” signs that have blanketed the city in promotion of development throughout Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s tenure. Democratic gubernatorial candidate Chris Kennedy has recently called out the mayor’s “strategic gentrification” of areas such as Bronzeville.16 Emanuel supported the school board’s closure of 50 public schools in one fell swoop17 and, under his helm, a surge in violence has earned the city the nickname “Chiraq.” It’s generally assumed that projects on the scale of the Chicago Architecture Biennial will have municipal support and cooperation. Still, the embattled mayor’s proud letter that prefaces the biennial catalog foreshadows that any critique of the city’s political situation may not be easily detected. Instead, the biennial spreads its bets more or less equally between practical design (such as MG&Co. of Houston’s division of the Cultural Center’s bookshop into differently colored quadrants—library, shopping, archive, discussion), friendly spatial alteration (for example, Mexico City’s Frida Escobedo’s skate ramp flattened into interior parklet), and Modernist hero worship (the ghost of Mies van der Rohe haunts throughout).

Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017– January 7, 2018. © Hall Merrick Photographers. Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial and Kendall McCaugherty.

Occasional nods in the direction of political reality can be found in print. Sarah Whiting’s essay in the catalog, “Figuring Modern Urbanism: Chicago’s Near South Side,” places the history of the IIT campus within the modernist urban planning trends that shaped Chicago in the mid-twentieth century and the later societal trends that led to their demise.18 She concludes with a call to recapture the initial hopeful spirit that encouraged such large-scale civic cooperation, though without acknowledging that such energies do exist today—in the form of investors and gentrification, rather than visionary architects. Edward Eigen’s “South Park: Proleptic Notes on the Barack Obama Presidential Center,” also in the catalog, is a swirl of historical quotes and debates that contextualizes the Chicago site selected for the forthcoming institution dedicated to the 44th president.19 It stops short of engaging the ongoing debates that have surrounded the location, such as the alteration of an Olmstead and Vaux-designed park, the awarding of construction contracts, and the possible economic impacts on neighboring residents.

Displayed at the exhibition’s entrance were freshly printed copies of And Now: Architecture Against a Developer Presidency.20 These essays were published by Columbia University’s Avery Review as a response to a letter by American Institute of Architects CEO Robert Ivy, published the day after the 2016 election, in which he made a collective first bid on any of the new president’s infrastructure projects.21 Pushback in the architecture community was immediate, and the sense captured in And Now is that contemporary architects and their students are ready for a wholesale rejection of their industry’s complicities and of the ways in which architecture has become like the Apple corporation: a Janus-faced performance of talking left and acting right.22 Outside of the opening reception, members of a climate action group called Architects Advocate were handing out flyers imploring “Make the Chicago Architecture Biennial Matter.” But once inside the British Petroleum-sponsored biennial, visitors found that spirit of a new architecture underground resistance less than readily apparent.23

Instead, one was left to sift through the three floors of installations searching for relevance, and finding it in unique instances. David Schalliol’s documentation of the dismantling of public housing across the city, Untitled (Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation) (2003–17), brings the city’s ever-present specter of demolition squarely into the 2017 biennial. His photographs capture Stateway Gardens melting into rubble, Cabrini-Green before it was supplanted by market-rate housing and a Target store, and Loomis Courts, one of the properties left standing but turned to private Section 8 housing.24

David Schalliol, Untitled (Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation), 2003–17. Ten prints installed within Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner, Five Rooms, 2017. Installation view, A Love of the World, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017–January 7, 2018. © Tom Harris. Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Part of A Love of the World, curated by Jesús Vassallo, Schalliol’s photographs are mounted in the Cultural Center’s awkward Landmark Gallery. In one of the site-specific commissions for the biennial, the gallery’s narrow space is divided up by an enfilade set of structural tiles, “a material commonly used in train stations, public schools, recreation centers, and other municipal buildings,” as the Chicago architects Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner describe them.25 Side-by-side with images of lone, desolate project buildings and sharing the same utilitarian aesthetic, one cannot shake the feeling of being inside the next building about to be turned to rubble, and then to condos.

The biennial also includes films, for example The Property Drama (2017) by Brandlhuber+ and Christopher Roth, which screens on a loop in a darkened booth. The Property Drama asks probing questions about land and ownership in relation to the commons in Central Europe. The subjects of the film philosophize about the values of and challenges to shared resources and community ownership, ideas that resonate in a city that has eliminated public housing, schools, and outsourced more and more city services to private companies.26 Aires Mateus’s Ruin in Time (2015), which also plays continuously in the Cultural Center, walks viewers through halted construction at two sites in Portugal. These abandoned, unfinished houses now serve only to remind us of their promises and foundering, and to recall similar small-scale boondoggles instantly familiar in debt-ridden Illinois (and elsewhere in the United States).

An installation of drawings and models by ZAO/standardarchitecture of Beijing shares the needed perspective of architects operating in a country that is building and demolishing at speeds and scales that far surpass Chicago’s. Make New Hutong Metabolism charts a way forward in anticipation of further threats to the traditional hutong neighborhood layouts in older sections of the Chinese capital. The architects frankly criticize both the forces that want to wipe out these alleyways and those who would preserve them in vitrines.

The biennial makes efforts to extend beyond the Cultural Center, occupying venues across the city. Photographer Lee Bey’s exhibition Chicago: A Southern Exposure, at the DuSable Museum of African American History in Washington Park, documents the South Side’s architectural classics, placing vernacular works alongside projects by notable designers. The exhibition makes a case for what may need to be fought for in an often-maligned area of the city endangered by future speculation. In a partner program at the Beverly Arts Center on W. 111th Street, Bey, architect James Gorsky, and photographer Rebecca Healy mounted Elevation: The Rise of Beverly/Morgan Park. The exhibition placed the neighborhood’s architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright, H.H. Waterman, Walter Burley Griffin, George Washington Maher, and Edward Dart in a geographic chronology reaching back to the Ice Age glacier that formed Southwest Chicago’s hilly topography. The photographs in both Chicago: A Southern Exposure and Elevation—of buildings in use, buildings being torn down, buildings as stylistic declarations, buildings representing lifestyles—present architecture to a public with the same level of discursivity found in the Cultural Center but without the solipsism, demonstrating a potential direction for future Chicago Architecture Biennials.

What if the next edition skipped the Cultural Center installation and spread the entirety of the Biennial’s energy to the three off-site locations and six collaborating venues in separate sections of the city that were included as only auxiliaries in this version—DuSable and Beverly plus the DePaul Art Museum in Lincoln Park, the Hyde Park Art Center, the National Museum of Mexican Art, and the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture? Dispersing the exhibition entirely throughout the city, like Germany’s decennial Skulptur Projekte Münster, could be a step toward rectifying the sense of aloofness in this biennial’s central hub. If New York-based WORKac’s Power Point-like preservation study of a 1930s art deco building in Beirut were moved from its pop-up installation space in the Cultural Center to a cultural battleground like the Pilsen neighborhood, could its models and renderings find an audience that palpably understands the kinds of real estate development forces that would seek to demolish, and thus necessitate the saving of, a building in Lebanon? And mightn’t they find strategies that could work as well in Chicago?

Make New History is an “argument about architecture’s need to reset itself—and rely on itself,”27 writes architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, paraphrasing the curators. Every discipline takes its moments in the mirror,28 but as contemporary architecture exhibitions proliferate at all scales—from low-budget student shows and architecture-focused galleries to glossy new biennials—it is valuable to question their ability to activate visitors in following and forming their own chains of signification outward from the works shown.

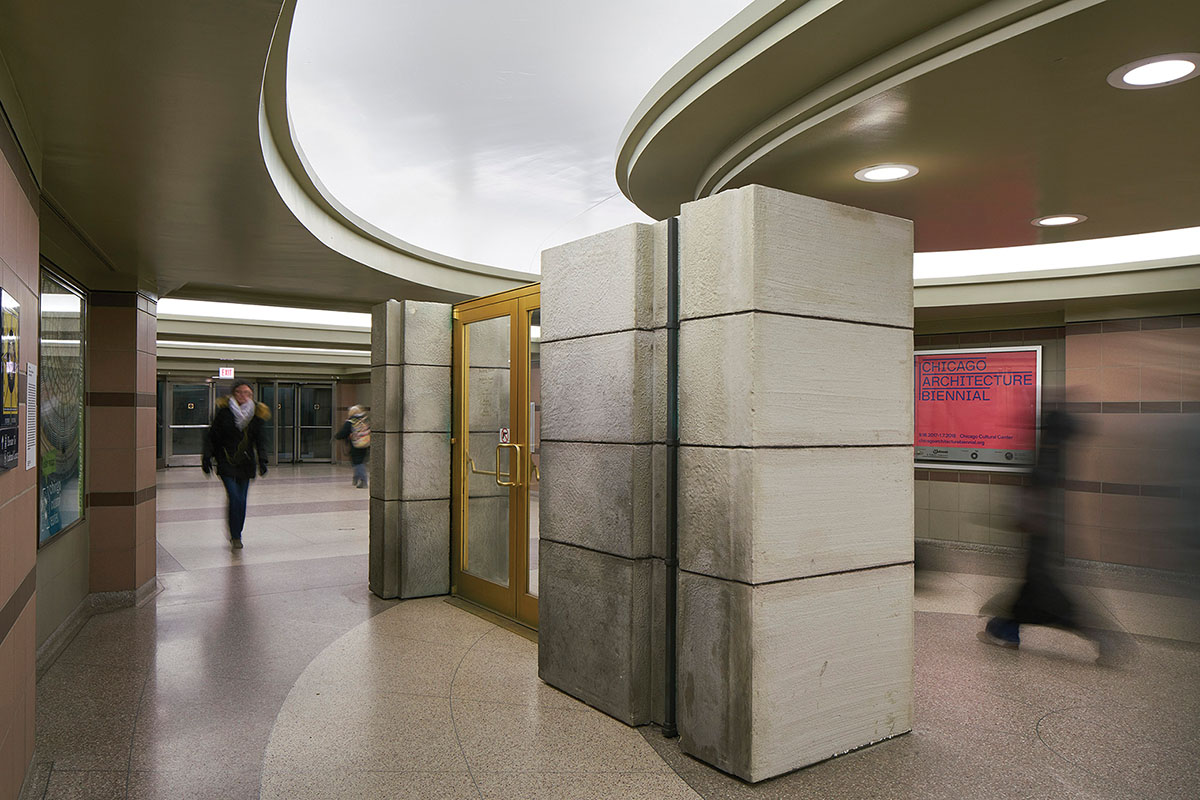

Erin Besler and Fiona Connor’s Front Door (2017), which duplicated the Randolph Street entrance of the Beaux-Arts Cultural Center, offers another example of the capacity of an exhibition to radiate out from its center. The artists reconstructed the heavy stone doorway, with its glass and bronze-anodized aluminum doors, in the underground pedestrian walkway (Pedway) that trails through the Loop from buildings to parking lots to trains. The artists then imitated the Pedway’s fluorescent lighting, bringing the Chicago underground up to street level by installing glowing tubes in the window displays that bracket the original entryway. Commuters in the Pedway navigate past Besler and Connor’s free-standing, 1:1 scale doorway (which sits with doors closed in front of the elevator that takes one to the Cultural Center lobby) much like Romans walking by ruins on their way to work. Pronounced and unobtrusive at once, Front Door becomes another layer of the physical and experiential site of the subterranean city, redirecting one’s attention toward other often overlooked spaces and conditions.

Erin Besler and Fiona Connor, Front Door, Part 2, 2017. Mixed media. Installation view, Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017: Make New History, Chicago Cultural Center, September 16, 2017–January 7, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Chicago Architecture Biennial. Photo: Andrew Bruah.

Bits of the Parthenon, Angkor Wat, the Great Pyramid, Rouen Cathedral, Lincoln’s Tomb, the Great Wall of China, Taj Mahal, and Hagia Sofia stud the neo-Gothic exterior of Tribune Tower at street level.29 Since its construction, these and many other building fragments have been inserted into its base. The first ones were pilfered by Tribune correspondents at the request of then-publisher Col. Robert R. McCormick (1880–1955). The broken off pieces function as a permanent outdoor exhibition and sample platter of global heritage sites. Their operation is magnetic: one is drawn in to read the plaques, then one’s thoughts are catapulted to images of far-away lands, the looted rock’s origin story, or the concept of the American abroad. Their pull offers some advice for the 2019 biennial curator: Viewers will participate more readily in the depths of histories, with their twisted social and political entanglements, than in the insularity and make-believe that marks the 2017 edition.

Is an architecture exhibition under any obligation to empathize with the place in which it is presented? Is an architecture exhibition intended to be an encounter with context or refuge from it? Asking over 130 (mostly) out-of-town practitioners for reflections (likely to be overwrought or underinformed) on Chicago’s specific struggles would carry obvious risks and dismiss 50 years of denunciation of the discipline’s panacea tendency in the early twentieth century, when Modernism was going to save us all. We are no longer clamoring for architects to supply grand “fixes” for the city today, but if the Chicago Architecture Biennial—a highly publicized mega-event of spatial thinking—cannot be a place for analysis of the physical spaces and places of its host city’s conflicts, then the biennial dooms itself to being a tourist in its own town.

Anthony Carfello is the Deputy Director of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House.