Trajal Harrell’s eight-part series, Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church, revolves around a central question: “What would have happened in 1963 if someone from the voguing dance tradition would have come downtown to Judson Church to perform alongside the early postmoderns?”1 Harrell began working with this question in 2009, and has since initiated several unrelated projects, most recently involving the pioneering Butoh choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata. Yet Twenty Looks has strongly shaped Harrell’s identity as a contemporary choreographer concerned with the re-interpretation of historical sources. The penultimate episode in Harrell’s series—Judson Church Is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure)/Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at The Judson Church (M2M)—premiered in 2012 and continues to tour widely; it has been presented recently in Canada, Portugal, Switzerland, and Greece, in addition to Los Angeles. It is the only dance in the series that reverses Harrell’s guiding question, rephrasing it to send the imagined postmodern dancer uptown.

Harrell’s guiding question alludes, on the one hand, to New York’s ongoing ball scene, where virtuosic performance and fierce competition belie resilient social bonds. While ball culture can be traced to 1960s Harlem (with evident precursors even earlier), balls are now found in “almost every major city in the United States and Canada,” drawing mostly, if not exclusively, Black and Latino participants.2 On the other hand, Harrell references the Judson Church, an institution standing at the south end of Manhattan’s Washington Square Park that still serves as a place of worship and a performance venue. In 1963, the church was at the height of its association with mid-century vanguardism, hosting a concert series that has been deemed the “seedbed for post-modern dance.”3 The 1962–64 concert series set several monumental dance careers into motion, including those of Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, and Deborah Hay. It also drew contributions from visual artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Robert Rauschenberg, and Robert Morris, which explains the interest that Judson has long garnered from art historians in addition to dance historians.

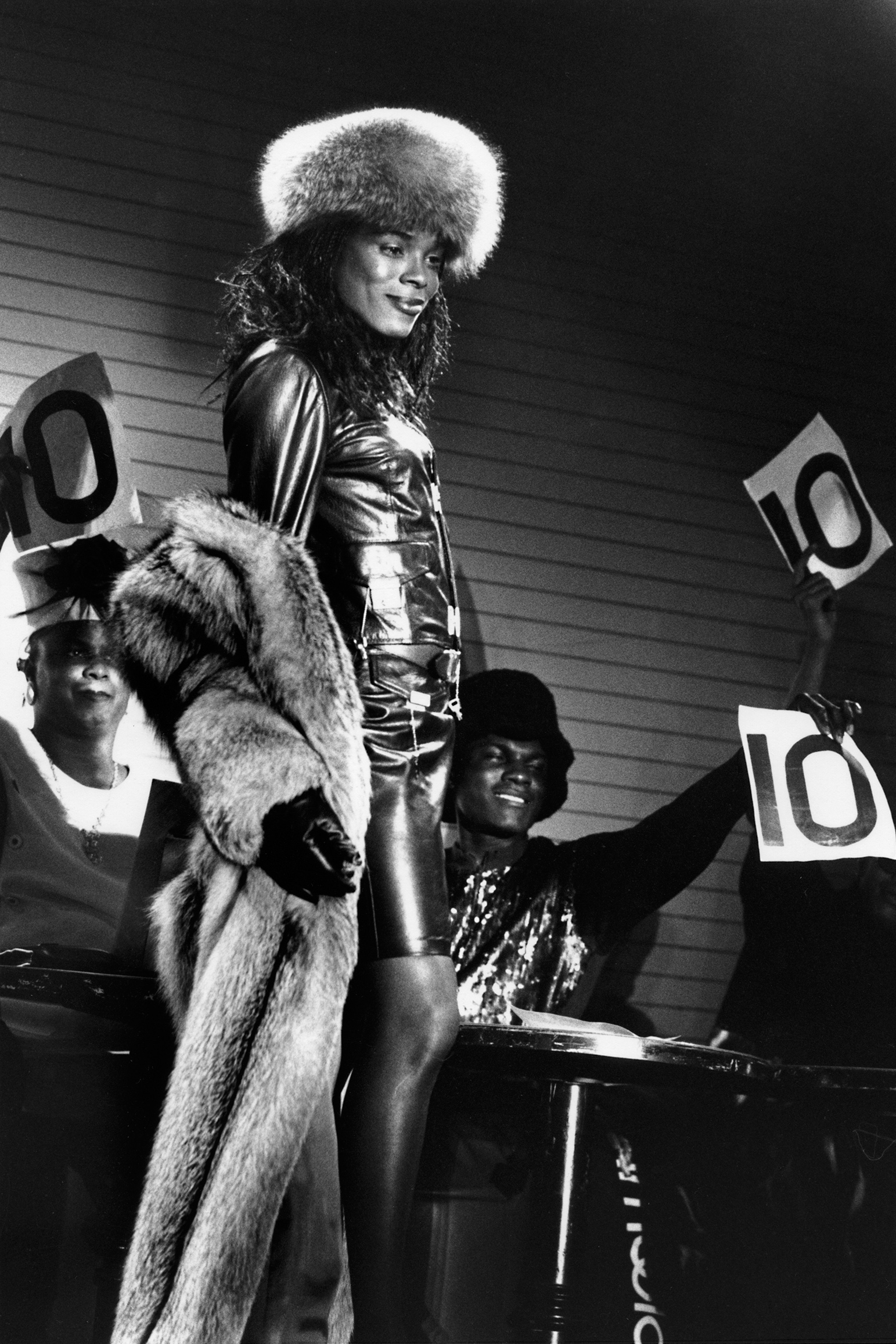

Chantal Regnault, Tina Montana, Avis Pendavis Ball, Red Zone, NYC, 1990. Published in Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City, 1989–1992 (London: Soul Jazz Books, 2011). © Chantal Regnault.

Investing in the “historical impossibility” of his proposed cross-cultural exchange, Harrell leverages a presumed polarity between Greenwich Village and Harlem; between the activities of a white cultural elite and those of a marginalized Black and Latino subculture; between an aesthetic of minimalism and neutrality versus one of flamboyant theatricality.4 Harrell has been drawing out the productive potential of this impossibility for years, but the longer Twenty Looks circulates in theater, festival, and museum contexts, and the more his “what if” question surfaces in promotional language, reviews, and academic scholarship, the more these signifiers—“voguing” and “Judson”—threaten to collapse under their own weight. When did Judson-era aesthetics become synonymous with a rejection of theatricality, with a “neutral” performance aesthetic winning out over the play of identity signifiers along axes of race, gender, class, and sexuality? And with respect to the ball scene, recent research has made clear that serious appraisals must contend with the discursive and cultural labor that undergirds participation, especially the familial bonds between “house mothers” and their “children.”5

To imagine a collision between these two cultures, then, must mean going beyond the aesthetic features of performance styles (even if a diversity among individual artists is aptly acknowledged). It must mean taking into account the way in which physical practices give rise to complex ecosystems of social practice. The Judson concerts benefitted from a famously “democratic” collective energy, with participants moving in and out of the loosely organized group at will, contributing when and as much as they liked.6 Within the social structure of the balls, however, membership revolves around an entirely different, and much more urgent, sense of belonging, one that actively redresses, through sustained community support systems, the acute vulnerability of queer subjects of color.

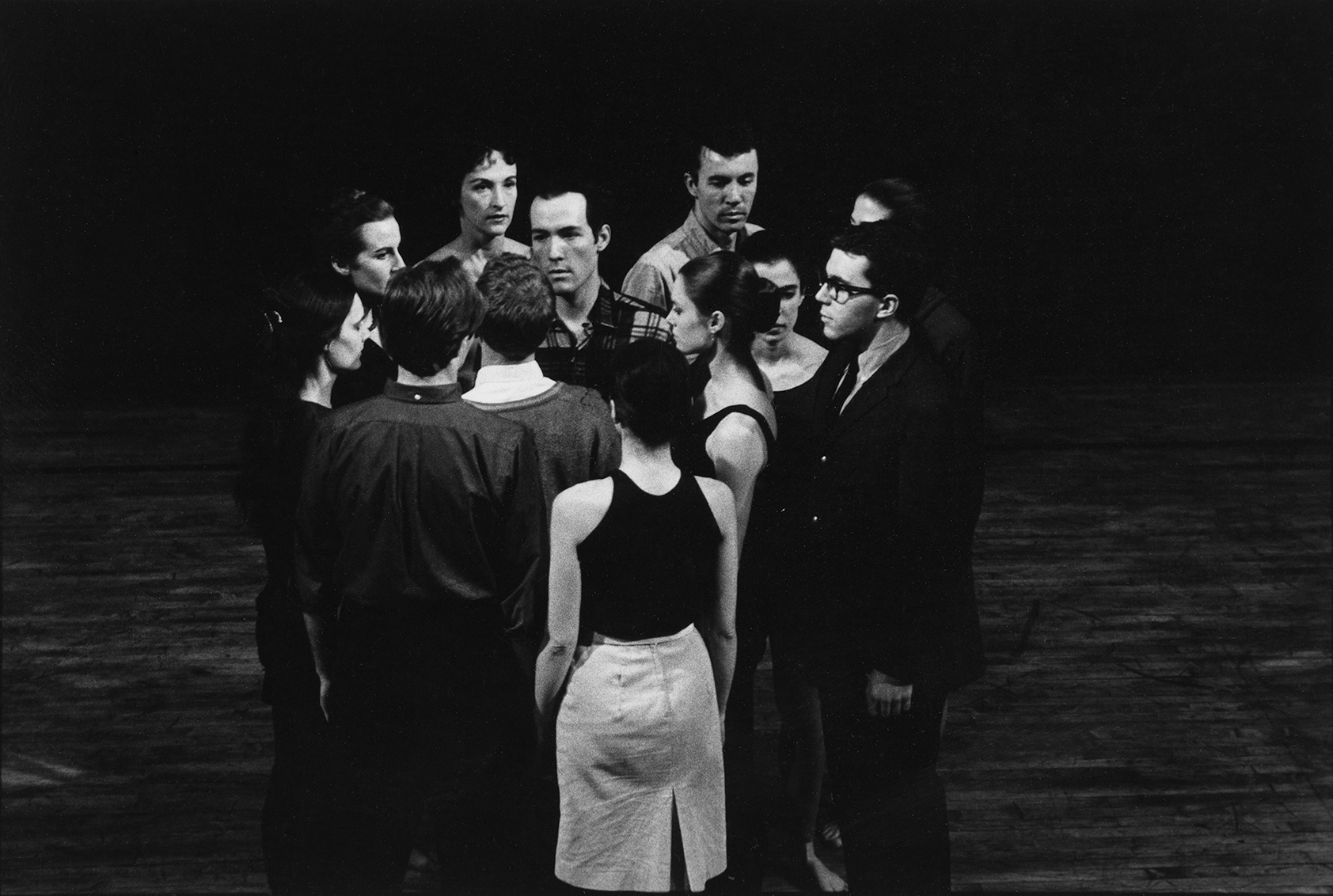

Yvonne Rainer, We Shall Run, 1963. Performance as part of A Concert of Dance #3 at Judson Memorial Church, and featuring Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Philip Corner, June Ekmna, Malcolm Goldstein, Sally Gross, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Tony Holder, John Mordan, Yvonne Rainer and Carol Scothorn. Courtesy of Fales Library. New York University. Photo: Al Giese.

In Twenty Looks, Harrell does go beyond aesthetics; across the work’s eight iterations, he contends with multiple points of intersection between Judsonite and voguing cultures. The full range of this research is not necessarily visible from all vantage points, however. At 50 minutes, M2M is one of the shorter dances in the series, a spare trio for three male-bodied performers: Harrell, Ondrej Vidlar, and Thibault Lac. While they wear long, sheer tunic dresses for much of the piece, there is little variation or play in gender performance; nothing, certainly, that comes near direct citation of the ball scene’s famously well-developed “six-part” gender system.7 Harrell approaches additional reference points with a light touch as well, eschewing some of the subject matter that crops up elsewhere in his series, for instance, the Greek tragedy, Antigone. The resonance between ball houses and the fraught lines of filiation in the Greek narrative are most fully developed in Antigone Sr./Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (L)—a dance for five performers running nearly three hours.

I saw Antigone Sr. (L) at Los Angeles’s REDCAT Theater in 2014, and I remember it as an explosion of sound and light, with the cast wrapping themselves in amazingly bizarre approximations of high couture, strutting amid Harrell’s scathing (but charming) house-mother-style exhortations. There were quieter notes as well, hinting at the melancholy of historical recuperation. As Clare Croft notes, in a dual review of Antigone Sr. (L) and M2M for the 2013 American Realness Festival: “If Antigone, Sr. (L) felt touched by loss, then M2M was overwhelmed by grief. It embodied a person fighting to avoid coming undone.”8 I agree with Croft regarding Antigone, Sr. (L); the dance-party pinnacle there felt communally, inclusively cathartic. Regarding M2M, though, I didn’t see the fight. The extended high-energy dance sequence near the end seemed literally to exhaust its performers, with the trio coming up against the impossibility of historical re-embodiment with resignation.

Trajal Harrell, Antigone Sr./ Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (L), 2012. Performance at New York Live Arts, New York, NY, April 25–28, 2012. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Miana Jun.

While Antigone, Sr. (L) makes full use of the theatrical proscenium, M2M is Harrell’s “custom-made” iteration. The relative bareness of its mise en scène makes the dance amenable to a range of contexts. At the Hammer, audience members were directed to the museum courtyard, site of much of the series, In Real Life: 100 Days of Film and Performance, where M2M was positioned as the most high-profile live performance.9 A square of white flooring identified the performance space and plenty of white folding chairs were lined up along one of its longer sides. I arrived early and watched these fill up, with spectators crowding into standing room at the back and sides. The sun was curiously muted that day, and without being cold it was breezy. The air stirred a portable rack of those sheer black costumes, placed in one corner of the performance space; they were further animated by a low fan, which was whirring even before the performers came into view.

At one point Vidlar appeared, walked over to the rack, and fussed a bit with the dresses. But it was Lac who emerged to perform an official introduction, or what André Lepecki calls a signature Harrell “pre-beginning.”10 Lac spoke into a handheld microphone, welcoming us and elaborating the voguing/Judson provocation and making special mention of M2M ’s unique reversal. As Lepecki suggests, the pre-beginning “announces the supposedly actual beginning…which does not start but already continues.”11 Indeed, Harrell held off revealing himself, using surrogates to set things going and stepping into a dance already in motion. Even so, motion was de-emphasized for the bulk of the first half, with a spectator’s focus drawn to the mere presence of the three performers. They sat in loose triangulation on chairs or benches, lost in the plenitude of near-stillness. Harrell was soon singing, face contorting to produce a deeply resonant sound. Vidlar sat closer to the audience, gazing placidly outward and gently, maddeningly repeating: “Don’t stop. Don’t stop. Don’t stop. Don’t stop.” In addition to vocalization, Harrell also introduced recorded sound as if making a mix tape, letting a Gillian Welch song (wholly ahistorical and obscurely personal) play all the way through, letting us watch him and the other performers listen.

Judson Church Is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) / Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church, 2017, documentation image, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 14, 2017. Photo: Justin Sullivan.

The opening section went on and on, slowly accruing tension, inextricably linking the trio though they never exchanged glances or touched. I found it brave for Harrell to reveal the un-spectacular and gradual coalescing of his ensemble. Dance audiences, and certainly dance audiences in the museum context, should be familiar with encountering minimalist movement. I’m thinking of Maria Hassabi’s recent exhibition at the Hammer (Plastic, 2015), where dancers slid so slowly down the central staircase as to make their movement nearly imperceptible.12 Yet I could feel the tension building amongst spectators throughout this section: When would they do something? Harrell eventually rewards his M2M audience with an unhinged battery of tippy-toed catwalking, riotous house-dancing, face- serving, and even a hint of those recognizable voguer arms (delivered by Lac). Yet he enshrouds that action with meaning by holding the commotion at bay, working his way slowly into a mixed-up corporeal history that never was, until now.

If you stumbled into the Hammer by chance that day, and didn’t read the provided program, you would likely not even register the dance’s references to Judson and voguing. Harrell has been utterly explicit regarding his disinterest in historical re-enactment, or anything that might betray a sense of nostalgia. In an interview with dance historian Thomas DeFrantz, Harrell explains that the project is aimed at historical “omissions” and at addressing such omissions by uncovering “future possibilities.”13 By conflating voguing and postmodern dance, Harrell does not correct the historical record by according the same importance to early-1960s voguers as has been accorded to the Judson artists. Nor does he establish historical coherency by dwelling on the discovery of mutual aesthetic concerns, although he does acknowledge overlapping concerns, most notably a shared obsession with walking.14 Rather, he seeks productivity from within the gaps, failures, and exclusions of the historical record: “I think that there are always omissions,” he reflects. “We know that about history. We know that history is a kind of fiction.”15 The essential narrativity of history is not a new assertion. Yet the question remains how one addresses or constructs narrative in and through the body, how one manifests future possibilities through the specific mechanisms of choreographic research.

Judson Church Is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) / Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church, 2017, documentation image, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 14, 2017. Photo: Justin Sullivan.

Harrell’s antagonistic relationship with re-enactment (and, implicitly, appropriation) is informed by his refusal to participate in “or draw creatively from any personal relationship to the community.”16 Though he began attending balls as a spectator in 1999, he came to them as an experimental choreographer with training in theater and visual art as well as an undergraduate degree in American Studies from Yale University.17 Harrell refuses to be the downtown experimentalist learning to vogue and then abstracting that physical language from its cultural context. In M2M, the ball culture references may be explicit, but he does not let them cohere into a recognizable facsimile, especially framed as they are by the unnervingly still introductory invocation. Yet Harrell’s avoidance of literal approximations of voguing also troubles entrenched assumptions about dance’s perpetuation. While it is important to remember the prominence of body-to-body transmission for those who uphold and build upon stores of embodied knowledge, it is also important to take into account the many strains of contemporary choreographic research that do not revolve around direct transmission.

In an essay addressing the historical re-imaginings of a French choreographic collective, the Albrecht Knust Quartet, Isabelle Launay puzzles over the “many instances where a contemporary dance has insistently undertaken—as a condition of its own renewal—a critique of past works that have been transmitted through the oral tradition.”18 She cites Hannah Arendt citing Walter Benjamin, who champions a “modern” way of relating to the past that replaces person-to-person (or in Launay’s formulation, oral) transmission with “citationality.”19 The Knust Quartet, which includes collaborators Dominique Brun, Anne Collod, Simon Hecquet, and Christophe Wavelet, restaged iconic dance works throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, including Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un Faune, as well as postmodern exemplars, such as Paxton’s Satisfyin’ Lover and Rainer’s Continuous Project/Altered Daily. For Launay, the text-centric concept of citationality reveals how artists discover points of departure by working with historical fragments rather than seeking a stable totality. In addition to drawing upon established sources, such as movement scores, the collaborators allowed themselves an open-ended relationship to history, affirming “themselves as the contemporary subjects of that narrative.”20 They drew upon official archives while also welcoming information derived from their own histories of rehearsal, production, and performance. Like the Knust Quartet, Harrell works with a keen awareness of his position relative to historical sources, allowing the research process to spin fragments into new centers of gravity— the incorporation of contemporary recorded music, the evident intimacy between performers, and the addition of Antigone references, for example.

Trajal Harrell, Antigone Sr. / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (L), 2012. Performance at Dansens Hus, Stockholm, April 4, 2012. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bengt Gustafsson.

While choreographic citation allows historical fragments to take on a life of their own inside of the creative process, it does become important to question how such fragments might then produce new totalities, not only within the work but also across the discursive landscape surrounding it. This includes promotional language, where presenters (including the Hammer) crystallize an opposition between the “formalism and minimalism” of the “Judson Church-period” and the “flamboyant and performative” voguer who “appropriates fashion vocabulary.”21 Or in the realm of criticism, as exemplified by a 2012 The New York Times review, in which Claudia La Rocco writes, “You can almost imagine a trio of Judsonite performers as artsy wallflowers, holding the line for their avant-garde principles…as ravishingly costumed voguers swirl around them.”22Even when the Judson/voguing juxtaposition is not thought in purely oppositional terms—La Rocco reminds us that “the Judson folks liked to party, too” and mentions some of the aesthetic overlap between Judson and voguing explored by Harrell—an opposition nonetheless tends to calcify.23 Likewise, in scholarly discourse: Madison Moore elaborates on the “Judson aesthetic” by citing Rainer’s “antispectacle propositions” as articulated in the NO Manifesto, and then quotes Harrell, who states that voguing allowed him to “turn all those ‘nos’ in the manifesto into ‘maybes.’”24 From this vantage point, citational fragments actually reduce complexity, narrowing the range of meaning derived from social and historical formations. When circumscribed so neatly, signifiers like “Judson” and “voguing” give spectators a leg to stand on as they parse the strands of meaning in Harrell’s deeply nuanced dances, but they also give rise to new exclusions and omissions.

For example, consider a reading of Twenty Looks that takes the figure of Fred Herko as representative of Judson-era aesthetics, rather than Yvonne Rainer (especially the narrow glimpse of Rainer that we get when considering her NO Manifesto in isolation). Herko was 27 years old in 1963, immersing himself in the world of downtown dance after a four-year scholarship program at American Ballet Theater. In Democracy’s Body, Judson Dance Theatre 1962–1964, Sally Banes references multiple firsthand accounts of Herko’s contribution to A Concert of Dance #1, a solo called Once or Twice a Week I Put on Sneakers to Go Uptown. Reviewers Jill Johnston and Allan Hughes describe Herko dancing barefoot in an elaborate headdress designed by Remy Charlip and modeled after an “African design.”Hughes praised Herko’s “sense of theatrical structure” and “charisma,” while Steve Paxton dismissed him as “campy and self-conscious…a collagist with an arch performance manner.”25 Only a year later, Herko leapt to his death from a fifth floor window on Cordelia Street in an amphetamine- induced haze. Particularly in light of the tragic brevity of his career, it is easy to see why he, like many of the Judson-affiliated artists, didn’t rise to Rainer’s level of visibility.

Herko’s association with Judson may likewise be tempered by his participation in Andy Warhol’s Factory, evident in films such as Rollerskate/Dance Movie (1963). Paisid Aramphongphan teases out many of the underreported threads connecting Warhol’s circle and the Judson artists, including another 1963 film called Haircut #1 that features Herko, Billy Linich (who was the eponymous haircut-giver in the film, as well as a frequent lighting designer at Judson), and James Waring (choreographic mentor to many of the Judson artists).26 Aramphongphan also discusses Jill and Freddy Dancing (1963), a four-minute film capturing Herko and Jill Johnston, who was an exhaustive chronicler of the Judson concerts romantically linked to the prominent choreographer Lucinda Childs. Aramphongphan identifies in these films a performance aesthetic emerging “partly out of camp sensibility and the queer subculture of which Herko (and Warhol) were part,” an aesthetic that was “rejected, if not openly denounced in homophobic terms, by the more art-world-connected side of Judson that has since dominated its history.”27 Aramphongphan is right to highlight the fact that it may only be parts of the Judson legacy that the “art-world” has found palatable, a concern worth echoing when Judson is invoked, via Twenty Looks, in museum contexts such as the Hammer and MoMA PS1, where the dance was commissioned.

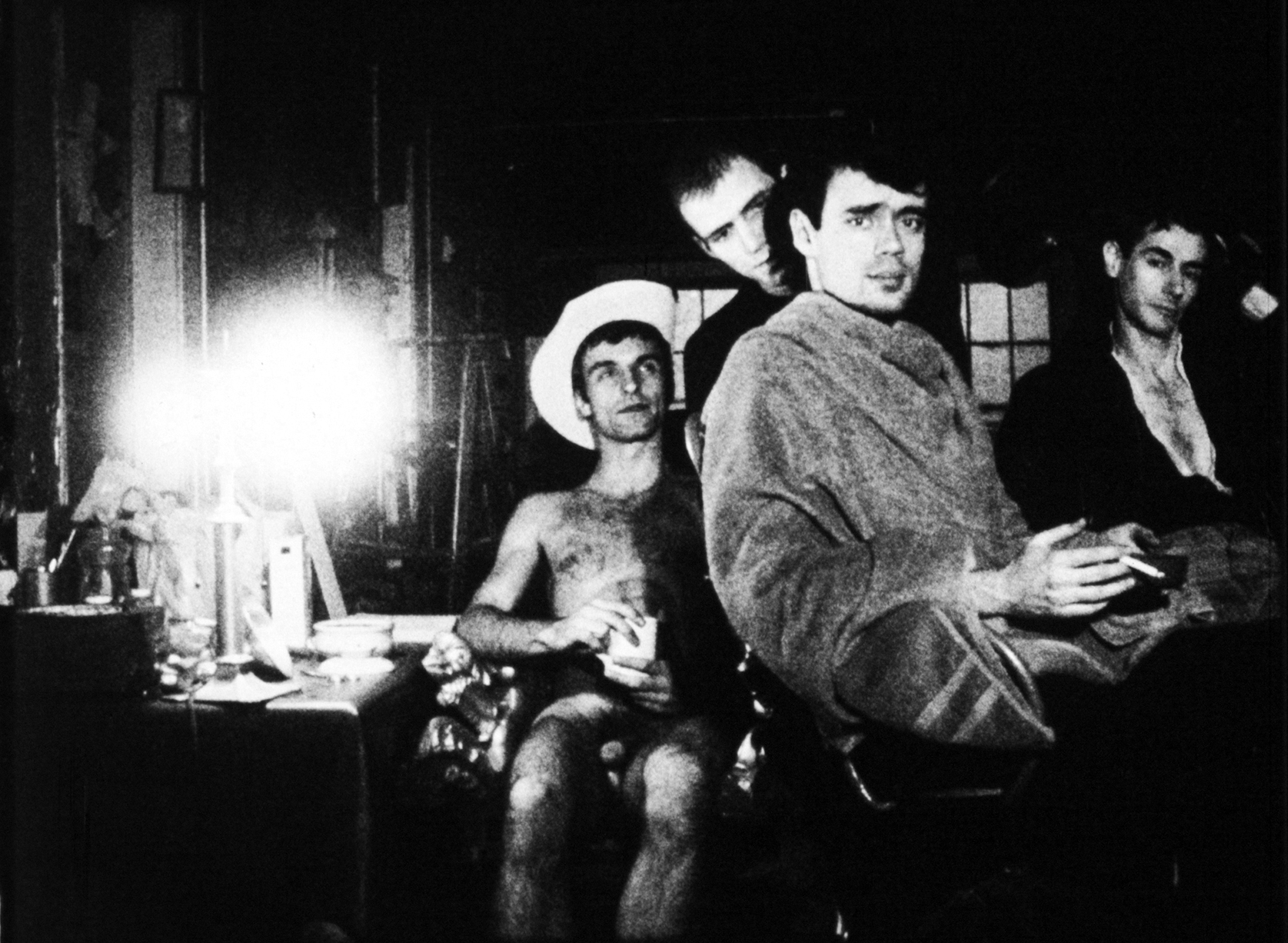

Andy Warhol, Haircut (No.1), 1963. 16mm film, black and white, silent, 27 min. at 16 fps. ©2017 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved.

Along these lines, many have pointed out the relative absence of people of color involved in the Judson concerts; this is important to acknowledge. Yet rather than merely remarking on it, why not leverage such assessments to confer visibility on a Judson-affiliated artist like Rudy Perez? In 1963, Perez was a young Puerto Rican from the Bronx who had studied with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham before initiating his choreographic career in the concert series. His breakout work was a 1963 dance called Take Your Alligator with You, a duet for himself an Elaine Summers in which the two performers struck poses “halfway between a bourgeois couple and a vaudeville team, their bodies stiff and mannered.”28 While Perez eventually moved to Los Angeles and enjoyed success as a choreographer and teacher, his contributions are routinely eclipsed in historical narratives that emphasize the “more art-world-connected side of Judson.” I mention Perez not to argue for a re-examination of Judson’s inclusivity, but rather to emphasize the connection between historical narrative and the intelligibility of subjects of color.

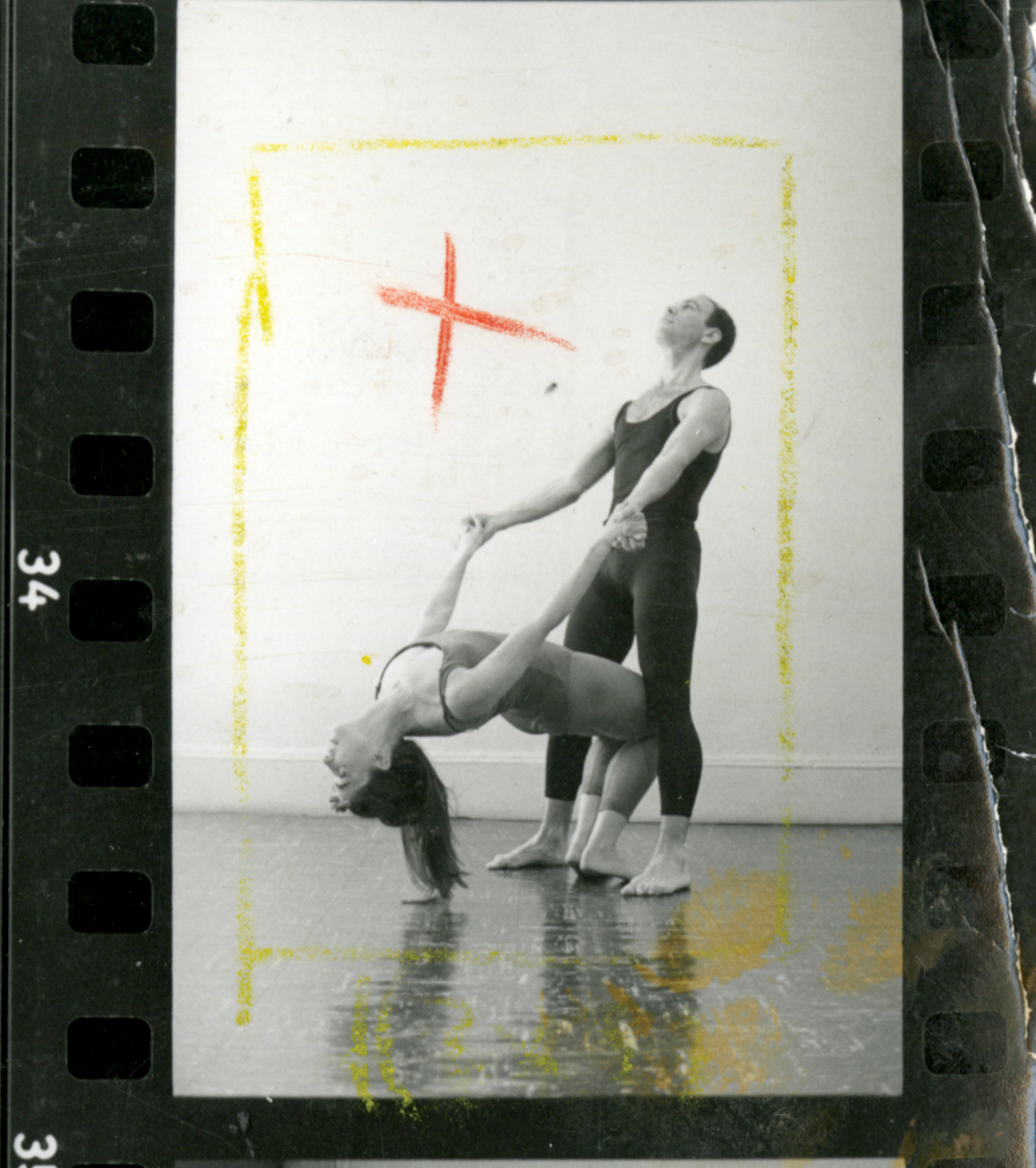

Rudy Perez and Elaine Summers rehearsing Take Your Alligator with You, 1962. Black-and-white contact sheet, dimensions unknown. Courtesy of Rudy Perez.

Indeed, many celebrate ball culture as a platform affirming the presence, and the artistry, of queer subjects of color. Here though, too, the fragment threatens to spawn totality, with Jennie Livingston’s 1991 film Paris Is Burning giving rise to an “academic cottage industry” unto itself. Theorists such as bell hooks, for example, argue that Livingston served up ball performers to be mocked by white audiences, and that performers themselves uncritically privilege white femininity.29 The prominence of and controversy surrounding Livingston’s film thrust a particular generation of ball performers into the spotlight, including luminaries of the late 1980s scene, such as Paris Dupree, Pepper LaBeija, and Willi Ninja. Lucas Hildebrand traces a pre-Paris history of the balls, from the nineteenth-century exploration of drag as “privileged straights’ transgression” to the popular Harlem events of the 1920s, where “white tourists ventured” to partake of the spectacle.30 By the 1960s, we arrive at the “modern ball circuit,” fully dedicated to the exclusive self-representation of queer communities of color. But even in the context of Paris Is Burning, as Hildebrand points out, LaBeija and another performer, Dorian Corey, remark on the dynamic evolution of drag aesthetics, where performers were apt to emulate Las Vegas showgirls, in the 1960s, and film actresses, in the 1970s; supermodels (and therefore publications like Vogue) did not become a prime focus until the 1980s.

Analyzing participant-observation from the late 1990s until the early 2000s, Jonathan David Jackson produces a useful choreographic analysis of ball culture’s multiple “ritual traditions.”31[[31]]Jonathon David Jackson,”Social World of Voguing,” Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement 12, no. 2 (2002), 27.[31]] Of the six categories he formulates, he notes that voguing was the only competitive style of the time that emphasized whole-bodied improvisation, while the other categories (including “runway,” “labels,” “body,” “face,” and “realness”) necessitate extraordinarily minimal movement patterns. Of the “face” category, for example, he reports that “competitors walk very simply toward judges and present their faces for inspection.”32 Such analysis challenges designations of ball culture’s essential flamboyance. Harrell’s work complicates it too, as he clearly mines a tension between theatricality and minimalism. He has uncovered intensely interesting links, for example between Judson-era investigations into the body’s actuality and ball performers’ expert play on illusion-as-realness. Such links reveal choreographic postmodernism and ball performance aesthetics to be in dialogue rather than in opposition. And again, fixating on voguing’s artifice leads one to overlook the highly developed, vitally important social bonds that underpin its aesthetics.

Jackson highlights this “ethic for kinship,” as does recent scholarship by Marlon M. Bailey, which focuses on the cultural and discursive labor at the heart of ball-scene social praxis.33 As Bailey argues, much of the popular and scholarly attention the ballroom community has received “underemphasizes both the conditions under which its members live and their use of performance as a way of surviving violence.”34 Bailey’s work demonstrates how ball children use the resources of the houses in concrete ways, with elders offering important advice on financial security, housing, and health care, especially related to gender transitioning.35 They also quite literally protect each other from attacks outside of the balls, where, as Bailey argues, “queer gender and sexualities signal to a would-be assailant that queers can be robbed and beaten, even murdered, with impunity.”36 So in addition to balls constituting a platform wherein marginalized subjects attain visibility, the social structure of the houses offers support and protection for participants as they navigate a hostile world outside. Harrell sees the formation of “intense communities” as another link between postmodern dance culture and that of the ball scene.37 Yet this link may offer clues about another important disconnect at the heart of Harrell’s “historical impossibility”: the incommensurability of two worlds with such different stakes around the enactment of community.

Trajal Harrell, Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (XL)/The Publication, 2017. Digital publication, downloadable at: https://hammer.ucla.edu/fileadmin/media/programs/2017/Winter_ Spring_2017/Trajal_Harrell-Twenty_Looks__XL__FINALE.pdf.

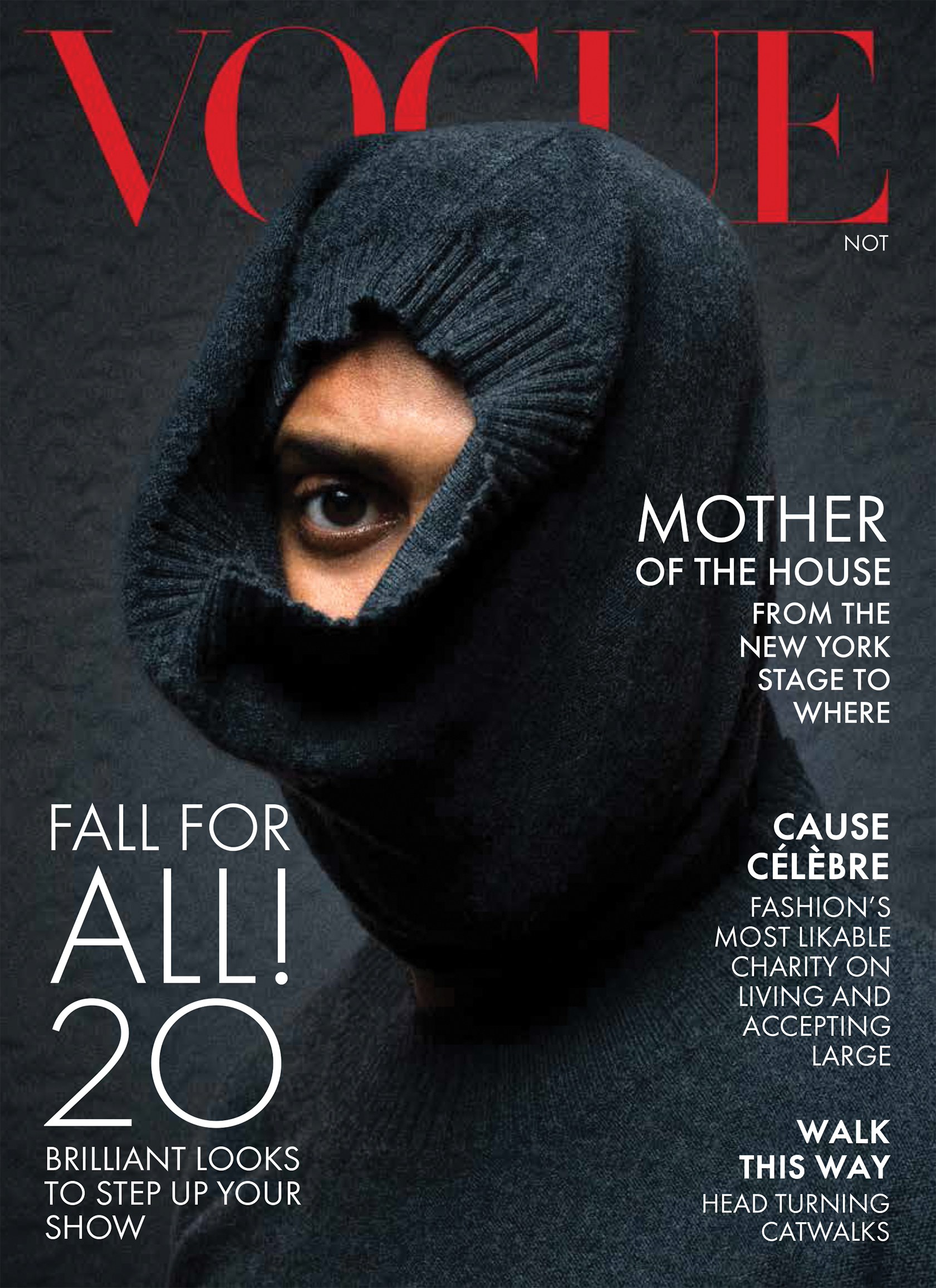

In January 2017, at the American Realness festival in New York, Harrell celebrated the release of Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (XL)/The Publication. This digital document is widely available;I downloaded it for free via a link on the Hammer event page. It’s a tongue- in-cheek play on Vogue magazine, Harrell’s effort to “vogue the magazine Vogue.”38 There are photos, letters from audience members, commentary in multiple languages, and in-depth critical writings by well-known performance scholars. It should be required reading for all of Harrell’s spectators but, at 322 pages, that seems unlikely. Like the series as a whole, it is messy, sprawling, complex, and often brilliant. It allows historical and conceptual fragments to proliferate, boldly frustrating attempts to fashion a totality. It signals the end of Harrell’s research process, but for those seeking to take stock of what, over the last several years, Twenty Looks has produced, it’s a nice point of departure, an occasion for imagining what was, or what never could have been.

Alison D’Amato is a researcher, choreographer, and performer based in Los Angeles. She has lectured in the Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at UCLA and the School of Dance at CalArts; she currently teaches dance history, theory and practice at USC’s Glorya Kaufman School of Dance. She holds a PhD from UCLA, an MA in Dance Theater Practice from Trinity Laban (London), and a BA in Philosophy from Haverford College. Her dances and scores have been presented widely in Los Angeles, most recently at PAM Residencies, Pieter Performance Space, and HomeLA. For more, visit http://alisondamatodance.com.