A breezy pass through the exhibition Landscape Confection at the Orange County Museum of Art elicits a first impression of “confection — yes, landscape — maybe.” Confection, in its various meanings, is an apt title: it can mean something put together from varied material; a fancy and/or sweet food; a medicinal preparation usually made with sugar, syrup or honey; or a piece of fine craftsmanship.1 Confection is evidently closely related to taste, and if this exhibition has a flavor, it is emphatically sweet. The landscape component, however, is unfortunately never qualified and appears throughout the exhibition as simply an arbitrary designation chosen to describe a sundry group of vaguely related artists whose works at times reference landscape traditions. The candy-like aspect of many of the works in the exhibition is often highlighted (dare I say insisted upon) at the expense at the work itself and at the expense of other possibilities within the genre of landscape. This makes for an eagerly attractive yet muddled exhibition.

Conceived and organized by Helen Molesworth, chief curator of exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts (where the show originated before traveling to the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston), the exhibition features about 50 works by 13 international and national artists. The show is undoubtedly pleasing to the eye and, upon closer inspection, a high level of craft is to be found throughout, but the promise of a show that examines or depicts landscape is ultimately tenuous and leaves the viewer hoping for more — and something different. Perhaps most importantly, the question of “Why landscape?” is not addressed. Molesworth, who certainly has a keen eye, seems much more interested in exploring the genre of new decorative painting and, in doing so, ably demonstrates the validity as well as the critical and practical values of contemporary decorative art in her selection of objects and in her catalog essay. Landscape, however, is treated as a “given” when — since it receives equal billing with the far more qualified and comprehensible term “confection”— it warrants explanation. Indeed, in the catalog essay, Molesworth not only dodges the subject of the landscape tradition (with the exception of a discussion of Watteau’s frothy fêtes galantes), but the very word “landscape” does not appear until page three, when it is mentioned only in passing. Perhaps most revealing is a curious statement made by Molesworth in an interview for the Columbus Dispatch, in which she vaguely claims: “We happen to be in a kind of landscape moment.”2

Decorative, within the context of this exhibition, is largely defined by palette and technique; Molesworth shows a predilection for a Rococo palette of pastels and an interesting use and range of materials, particularly those employed to create tactility, delicacy, and dimensionality. The stated goal of blurring the distinction between art and craft is ably achieved by the artists, but the curatorial emphasis on this distinction is, for the most part, unnecessary, as this blurring has already been achieved by earlier artists and commented on by countless critics. The artists are quietly ambitious in their conception of the materials at their disposal and do not engage this variety of materials (wax, plasticine, thread, fabric, silk flowers, etc.) to be simply charming, but instead to be vigorous and playful in their practice. They are much less self-conscious about their materials and less invested in feminine/masculine, craft/art dichotomies than the curator herself.

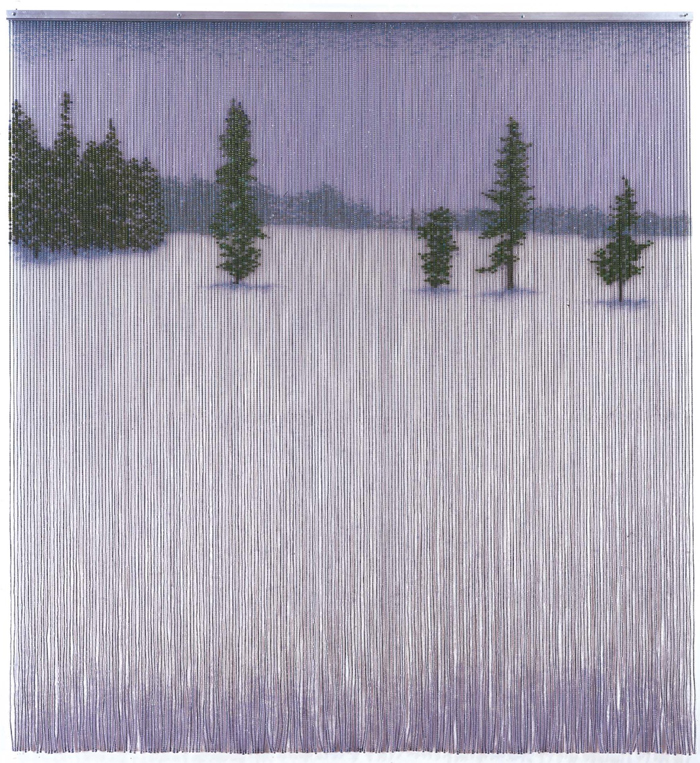

The work of Kori Newkirk is a stand-out in the exhibition with his stunning landscape “curtain paintings” carefully composed of plastic pony beads that hang from sleek, minimal aluminum bars. LK-3 (2004) depicts a deeply foregrounded snowscape, unpopulated but for a few young trees. Another work, Bam Bam (2003), depicts a dark night sky with a cityscape and suspension bridge below. The pixelated quality created by the hanging beads and white gallery wall behind gives the impression of falling rain (or snow in the case of LK-3) and as an image it is evocative of Whistler’s paintings of fireworks over London. Newkirk, selected for this year’s Whitney Biennial, plays dexterously with one’s expectations on many levels, including the viewer’s likely resistance to his chosen medium. Without looking at supplementary information, the viewer would probably not guess that Newkirk is an African-American male. An exploration of racial history and identity, albeit a somewhat tongue-in-cheek one, manifests itself in these pieces in his subtle decision to use thinly woven synthetic hair braids to thread the beads when he could more readily use filament. The hair coupled with the beads references African American hairstyles and hair extensions, and does so somewhat humorously due to the sleek aluminum bar and museum setting. A careful balance between sobriety and smart humor is struck.

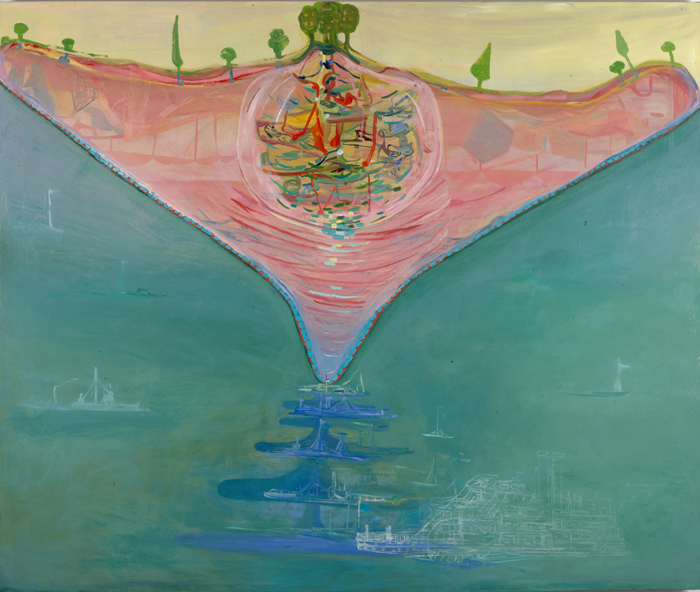

Paintings by Lisa Sanditz and, especially, Amy Sillman, likewise have much to offer. Sanditz’s folksy and bright canvases convey the artist’s sensitivity to and humorous regard for the American landscape and her personal experiences in it. The specificity of place in such paintings as 49th and Clarke Street Park, Oakland, California (2003) and Dolly Parton’s Peaks, Knoxsville, TN (2003), showcase the simultaneous banality and peculiarity of America. Curvaceous brushwork, a sunny, watery range of colors, and a youthful mood are combined in such works by Sillman as The Egyptians (2003), a coastal scene comprised of light-dappled water, surreally formed and costumed figures, and a grouping of sea birds. The circle of action in the painting’s foreground breaks down before your eyes into a series of abstract lines just as it builds back up into something hazily recognizable. One figure appears to ceremoniously proffer a gift, with the gift being a heap of levitating dots of color. Valentine’s Day (2001) similarly reads as hieroglyphics for a personal dreamscape, with its mysterious narrative featuring ghostly ships. Sillman’s apparent penchant for marine subjects recalls the work of such artists as Whitney Bedford and Tony de los Reyes, who have also exhibited what could be called “marine paintings” recently. A reinvigoration by contemporary artists of this “old-fashioned” sub genre of landscape is worth exploration.

Playfulness with materiality is much more of a concern than the creation of a narrative in much of the work in Landscape Confection, with many artists emphasizing the additive nature of their work. Neal Rock builds up pigmented silicon over armatures; Rowena Dring pieces together different colored fabric with emphasized stitches; Jim Hodges threads together silk flowers; and Ranjani Shettar creates an expansive web of colored thread and hundreds of beeswax balls, to describe just a few. The organic nature is especially lush yet delicate in Shettar’s contribution to the show, Vasanta (2004), the title of which means springtime in Hindi. The installation evokes both the spring landscape in its verdant colors as well as the human celebration that welcomes it. Jim Hodges’ similarly spring-minded piece From Our Side (1995), a scrim of silk flowers, is less successful, although related silk flower pieces not included in the exhibition such as This Way In (1999), in which the silk flowers are pinned to the gallery wall, are much more successful. These works using artificial flowers seem more a part of the “vanitas” tradition of painting than landscape.

Palette is seemingly misread in the paintings of Jason Gubbiotti, whose work does not fit comfortably into a landscape tradition. His abstract paintings are reminiscent of topographical maps and his color choices — ocean blue, sunny orange, and variegated green — signal aspects of landscape, but his concerns are more formal in nature. Gubbiotti’s fascination with the “building up” component of art-making is evidenced by the care and creativity put into the support structures for his paintings, with their beveled layers of wood, curving stretchers that wrap around corners, visible staples and canvas edge. The simultaneous rawness and delicacy of his paintings are akin to that of Shettar’s Vasanta, with which a diagrammatic quality is also shared. Gubbiotti’s work is perhaps the least feminine of the assembled artists, another thematic emphasis of Molesworth that goes hand-in-hand for her with the somewhat unusual materials employed by many of the artists. Gubbiotti’s paintings are amongst the strongest works included but due to their cool yet understated machismo, seem shoehorned into the premise of the exhibition. However, his paintings share a decided slickness with the work of Newkirk and especially, if uncannily so, with the fabric pieces of Dring.

Instead of acting as visual cue, the palette for other artists acts as veil. David Korty’s Prendergast-like paintings are incongruous compositions of light pinks and greens depicting such scenes of urban decline as garbage on a hillside and crowded houses and cars. The veil of pastel color mercifully prevents one from being able to penetrate the image but gives the viewer a sense of just how stifling that cotton candy-infused air would be if you could. There are other Rubénistes in the crowd: Katie Pratt and Neal Rock, both of whom show at Kontainer Gallery in Los Angeles, could be described in this manner although the label of “artists concerned with landscape” would not be apropos. Rock’s candy-like wall sculptures — truly confectionary as they are created with the deft use of a pastry bag — are so sickly sweet they make your teeth hurt just from looking at them. Even with the inclusion of flowers or flower-like forms, the sculptures evoke not landscape, but rather function as grotesque hunting trophies of creatures from a pastel lagoon. Technically interesting, they fall flat ultimately, as do Pratt’s paintings. The respectively large number of works included by each of these artists did not help, with eight Pratt paintings and five Rock pieces while most artists had one to three representative works. Pratt’s work, scattered through most rooms of the exhibition, do little more than tie the various predominant colors of a given space together. This natural tendency to arrange the works in a room to “look good” together makes for a cohesive experience in terms of color but ultimately detracts from the seriousness of the work itself and some of the more interesting possibilities of grouping are lost or diminished. The pleasing color coordination tricks you into thinking the chosen artworks go together better than they do and runs the risk of feeling like good interior decoration. Obviously this installation choice riffs on the decorative qualities of the work in the show but this congruence does not permit the distance necessary to view the work. At certain points, the installation becomes a sort of “total environment” and can feel oddly oppressive. The wall text — itself featuring pretty filigree design—seemingly invokes Immanuel Kant’s definition of art when it describes Rock’s sculptures as “beautiful and useless, they flaunt their status as art objects.” Yet Rock’s sculptures are not any less useful than any other included work but are merely striking in their obnoxious immodesty and plenitude.

Molesworth is eager to find evidence of “the melancholic” in the majority of the work and this is occasionally accurate, as in the case of Michael Raedecker’s only included work, Blind Spot (2000), a small gray-hued painting tucked in a corner that could go unnoticed.3 The painting, largely composed of embroidery, depicts a possibly icy body of water, a modest dock, and a rustic building partly obscured by a mysterious fluffy ball of tangled thread. Blind Spot shares its dearth of figures with much of the other work in Landscape Confection. Nevertheless, the melancholy can simultaneously read as peaceful such as in the work of Dring, Newkirk, Gubbiotti, and Shettar. Exhibition wall text references the “isolation and loneliness of contemporary life” but this is a universal and timeless preoccupation. This potential (and ostensible) psychological theme is worthy of exploration, particularly in regards to the landscape tradition and specific legacies of artists like Caspar David Friedrich and Edward Hopper, but it is, like landscape itself, assumed here.

Curatorial choice in the context of group exhibitions is an easy target, especially when an exhibition is clearly the product of interwoven preconceived themes. And so it is a matter of opinion to say that it would have been better to have limited the exhibition to young artists who are more truly engaged in the landscape tradition and to have further limited it to wall works, perhaps even excluding photography. (The two included photography pieces, one by Jim Hodges and another by Janaina Tschäpe, seem out-of- place in this particular exhibition.) Artists such as Daniel Dove and Sandy Litchfield come to mind as worthy candidates for such an exhibition. Molesworth shows herself to be a well-versed and versatile art historian in her catalog essay, but certain received notions from the discipline of art history stand in the way of letting the best work in the show speak for itself. Landscape Confection is simply — and cannily — an evocative confection. However, the most talented artists included in the exhibition succeed in getting away from the decorative as tacit or empty, and ratify Molesworth’s claim that pretty pictures act upon us in complex and unexpected ways.

Jennifer Wulffson Goodell is a senior editor with the Bibliography of the History of Art at the Getty Research Institute.