In An Icelandic Saga, a series of 48 black ink drawings on Bristol board that fluidly wed image and text, Dorothy Iannone recounts the story of her 1967 voyage to Iceland. It was there she met the artist Dieter Roth, who greeted Iannone, her then husband James Upham, and their friend, Fluxus artist and poet Emmet Williams, as their freighter docked, “WITH A VERY FRESH FISH, WRAPPED IN NEWSPAPER UNDER HIS ARM.”1 Anyone familiar with Iannone’s work, in which erotic depictions of Roth often appear, knows the auspiciousness of this encounter: within days the pair had pledged their love for one another. A week later, on the morning of her return home to New York with Upham, she confessed and bought a one-way ticket back to Reykjavik for the following day. In 1978, the same year she composed the first part of the Saga, Iannone completed another set of autobiographical drawings, L’Adorable Trixie, a timeline of personal evolution. Describing again her meeting with Roth, she writes that it was the moment when she “LEFT FOREVER THE IDEA OF HOME AND STARTED THAT LONG DESIRED JOURNEY WHICH WAS HER OWN LIFE.”2

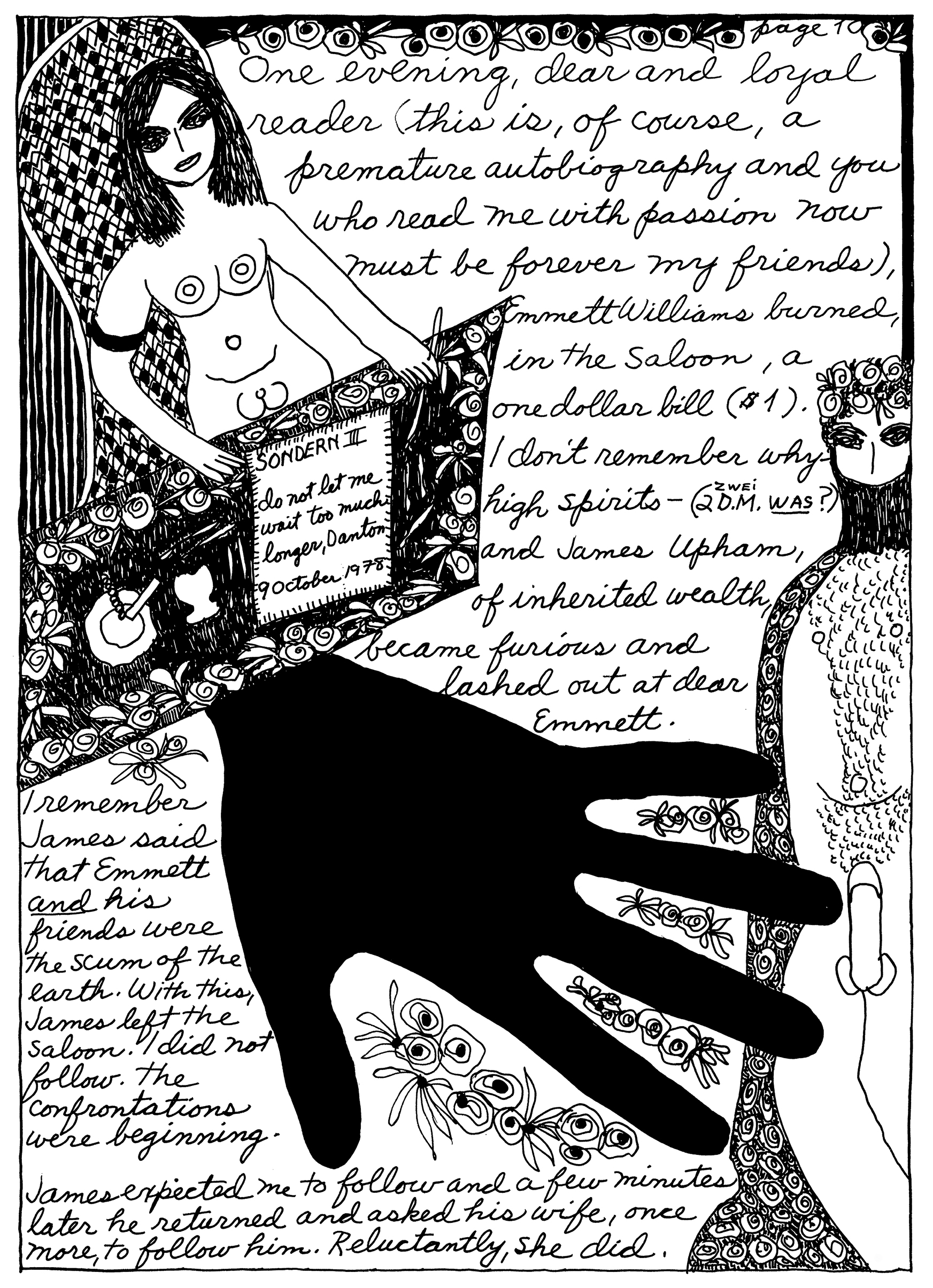

Dorothy Iannone, An Icelandic Saga, Part One (excerpt), 1978. Ink on Bristol board; 48 drawings, 15¾ × 11¾ inches each. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris.

Such a tumultuous turn of events—the dramatic break from both husband and homeland—would naturally change anyone’s life, but here the rupture is also tied to Iannone’s artistic development. She was born in Boston in 1933 and self-trained as an artist. Prior to the trip to Iceland, she had been making abstract paintings and collages in New York for more than half a decade and had transitioned to figuration shortly before leaving the United States. Most notable was an exhibition in 1967 at the Stryke Gallery, a downtown exhibition space she ran for four years with Upham, in which she showed small wood cutouts of popular figures, such as Bob Dylan, Norman Mailer, and the Kennedy family, with exposed genitals drawn on the outside of their clothes. But Iannone maintains that something powerful coalesced when she began her relationship with Roth, who was the first and most prominent of a number of muses. The work that followed—much of it portraying graphic amatory acts, with declarations of erotic devotion and happiness, as well as registers of pain and doubt often written directly onto figures’ bodies—is positioned as coming out of the revelation of a profound and liberating Eros or, as she later calls it (in a nod to mystical and Eastern philosophy), “ecstatic unity.” Even after her departure from Roth seven years later, the tenet of becoming one with another through erotic love as a form of deep spirituality, or as the meaning of art itself, would remain one of Iannone’s central themes.

An evangelist for sexual pleasure and unmitigated female sexuality, Iannone’s bold embrace of sex and love in her work is matched by an equally if not more robust drive toward narrative construction and inventive forms of autobiography. The notion of unity extends beyond pictorial representations of the fusing of lovers’ bodies to a yoking together of disparate points in time and place, truth and fiction, people and identities, as well as a compositional cohesion. One could be excused for occasionally confusing her art and her life, because at times she seems to purposely collide the two. At the same time, she consciously plays with persona, elision, pun, and self-reference, always asserting her role (often with humor) as the interlocutor between her experience and its application.

An Icelandic Saga—which opens Siglio Press’s recent volume of selections from 40 years’ worth of Iannone’s drawings, paintings, artist books, etchings, and writings, and is organized in two parts around a loose chronology of Iannone’s life with Roth and after—quickly becomes a mise-en-abyme. A two-page interlude deposited early in the work locates the artist in her Berlin apartment long after her trip, writing and drawing the text and image that her “dear and loyal” reader is now viewing. The interjection introduces another layer of time to the story being told. Afterwards, Iannone periodically alternates between past and present, as well as different points of view. This shifting occurs in both image and language, as in one drawing, where in a rounded, even cursive she describes a night of drinking on the freighter when Emmet Williams impishly burned a dollar bill, which enraged the wealthy Upham. Everything is written in first person, until the last line, where she describes resignedly following Upham out of the ship’s bar after he’s returned for her a second time: “James expected me to follow and a few minutes later he returned and asked his wife, once more, to follow him. Reluctantly she did.”3

While she often writes about herself as a character, the sudden change in perspective foregrounds this construction, concisely expressing the gap between her role as the dutiful wife and the liberated woman crafting her experience into art. This sense is given dimension and echoed by the drawings that border and break up the text. Iannone depicts herself sitting nude at a desk, perhaps completing or beginning another artwork: a page bearing the name of the German journal where An Icelandic Saga was first published, Sondern, rests on the table with a message inscribed to a new lover, “Danton,” dated to the present year of 1978. A large, shadowy hand bridges the distance to a masked male nude with an erect penis across the page wearing a cape and a crown of rosettes, which also border the desk and appear in between the fingers of the hand; they morph to become the pattern on the cape, cling to the top of the black outline framing the drawing and reappear many times again as a motif throughout the work.

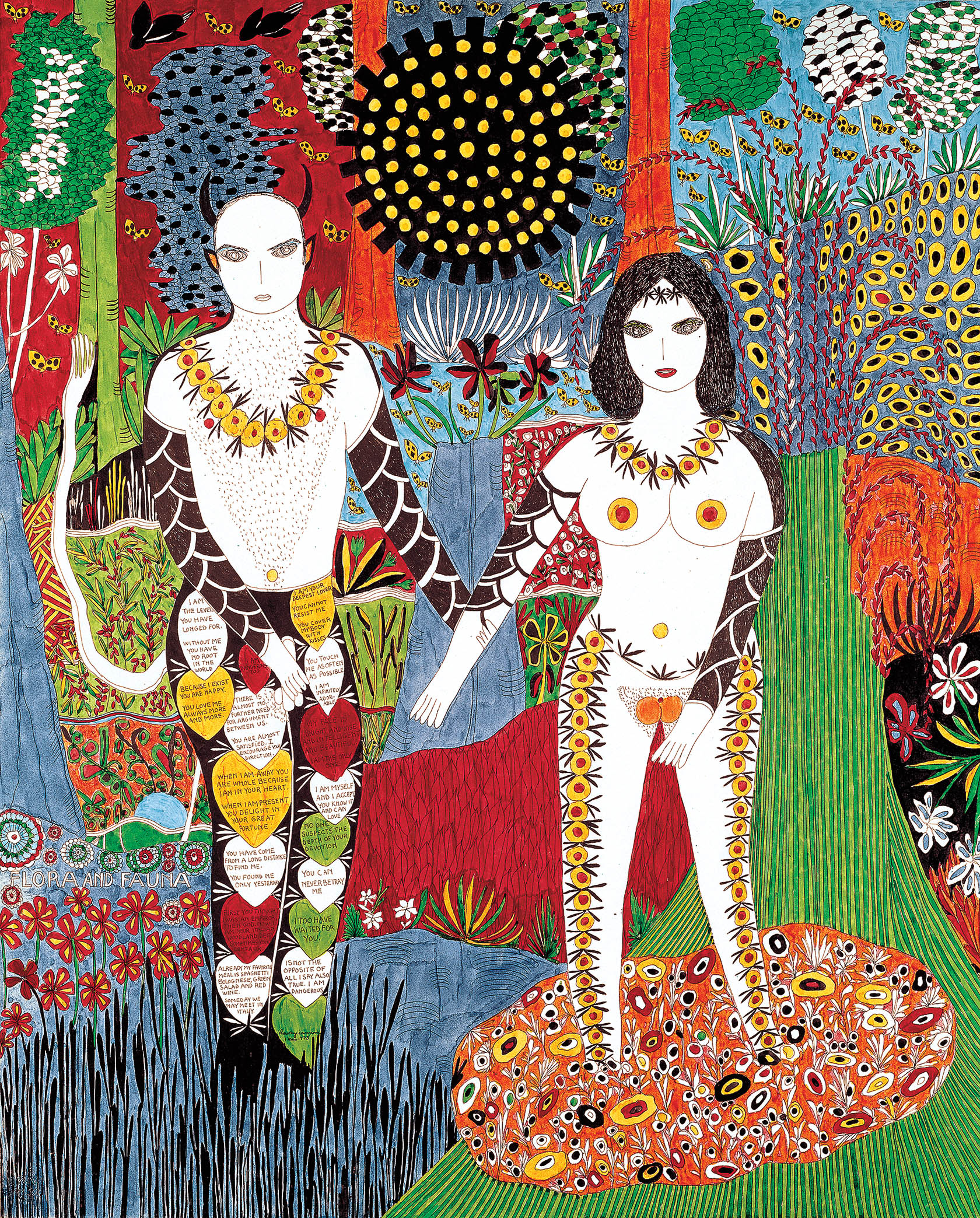

Dorothy Iannone, Flora and Fauna, 1973. Felt pen on Bristol board, 23½ x 28½ inches. Courtesy of the artists and Air de Paris, Paris. Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

Like the handling of the rosettes, the blurring or interchangeability of ornament, object, figure, pattern, and abstraction is a definitive aspect of Iannone’s style, one that results, in part, from her work’s relative flatness. Dialogues 1 and Dialogues IV (both 1967) are two series of six drawings each that progress sequentially and portray intimate, sometimes shape-shifting moments of domestic exchange between her and Roth. In the series, a square colored border decorated with flowers becomes, in various turns, the ground of a drawing, the floor of the space depicted, and a scrim-like curtain that the lovers appear against. Household furniture, such as Ankh-form beds, cushions that resemble wings or palm fans, tables, rugs, and tapestries, offers an occasion for brilliant fields of multicolor patterning. Iannone similarly adorns her figures, as with a later set of Dialogue drawings from 1968, where a momentary lapse or dismissal of her identity (after comparing herself to Marilyn Monroe) transforms “D.” into a mythical Grecian creature; the patterned wing forms now sprout from her back. In Ten Scenes, a silkscreen from 1969, two lovers take turns assuming varying positions of dominance and submission. Perhaps as a mirror of this evolving power relationship, Iannone noticeably shifts the figures’ physical appearance with each new configuration, rhythmically alternating color, pattern, and design in each scene.

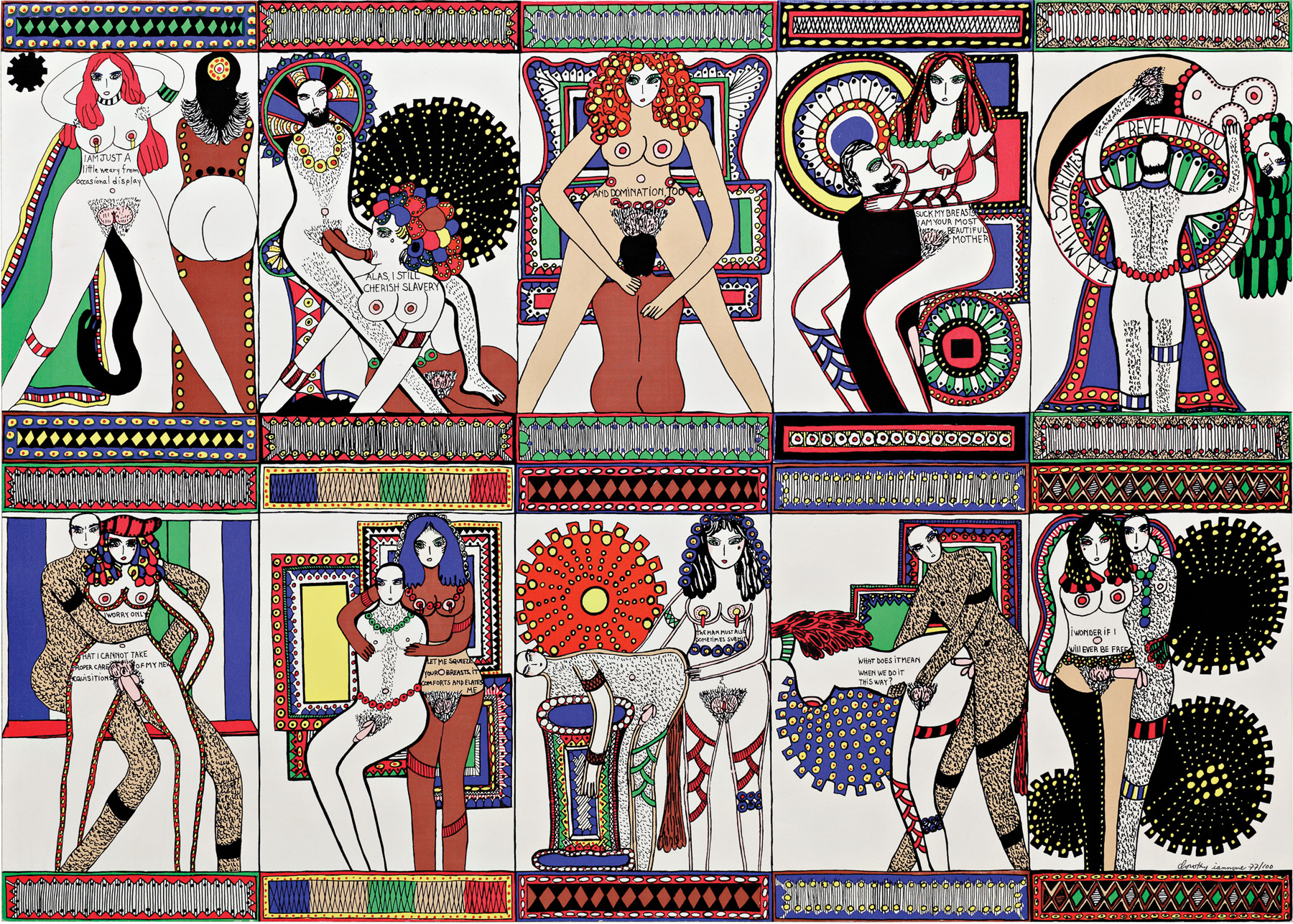

Dorothy Iannone, Ten Scenes, 1969. Color silkscreen on paper, 26¾ × 37½ inches. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul.

Such sumptuous and symphonic works conjure a wide range of possible influences. Writing about Iannone, critics have mentioned Egyptian painting, Byzantine mosaics, Japanese wood block prints, illuminated manuscripts, Medieval stained glass, fertility sculpture, Persian Miniatures, and Tantric art. (Author and critic Trinnie Dalton thoughtfully considers the artist’s connection to the latter in the book’s accompanying essay.) One could go on—Russian Icons, Art Nouveau, underground comics—but looking at a large selection of Iannone’s output together, what’s striking is the manner in which story imbues image, resulting in a visual world that feels both familiar and unique. Certain repeating designs—particularly birds, snakes, asses missing bodies, and, as Dalton writes, “the distinctive and various rendering of sexual organs, which are clearly characters in themselves”4—almost take on the role of musical leitmotivs. And since autobiography, at least in this collection, is so often invoked (a series of drawings is subtitled Notes For An Autobiography Part III [1979], for example, followed by a piece of writing the next year, Pieces In Autumn, A Continuation Of That Cunningly Titled Notes For An Autobiography Part IV) one also has the sense of a continuous, unified project that binds Iannone’s oeuvre together as one long story told and retold in a multitude of ways.

Indeed, this sturdy volume, which resembles a thick graphic novel, places emphasis on Iannone’s work as something to be read as closely as viewed. For the most part, Lisa Pearson, the book’s editor and publisher, takes pains to keep text and image on the same footing. She chooses extensively from the small-scale drawings and artist books Iannone began to make more regularly in the late 1970s (after multiple encounters with censorship over her painting and sculpture) and often supplies transcriptions of text from works that might otherwise prove difficult to read. The result is a focused look at a particular element of Iannone’s practice, not an exhaustive compendium of it.

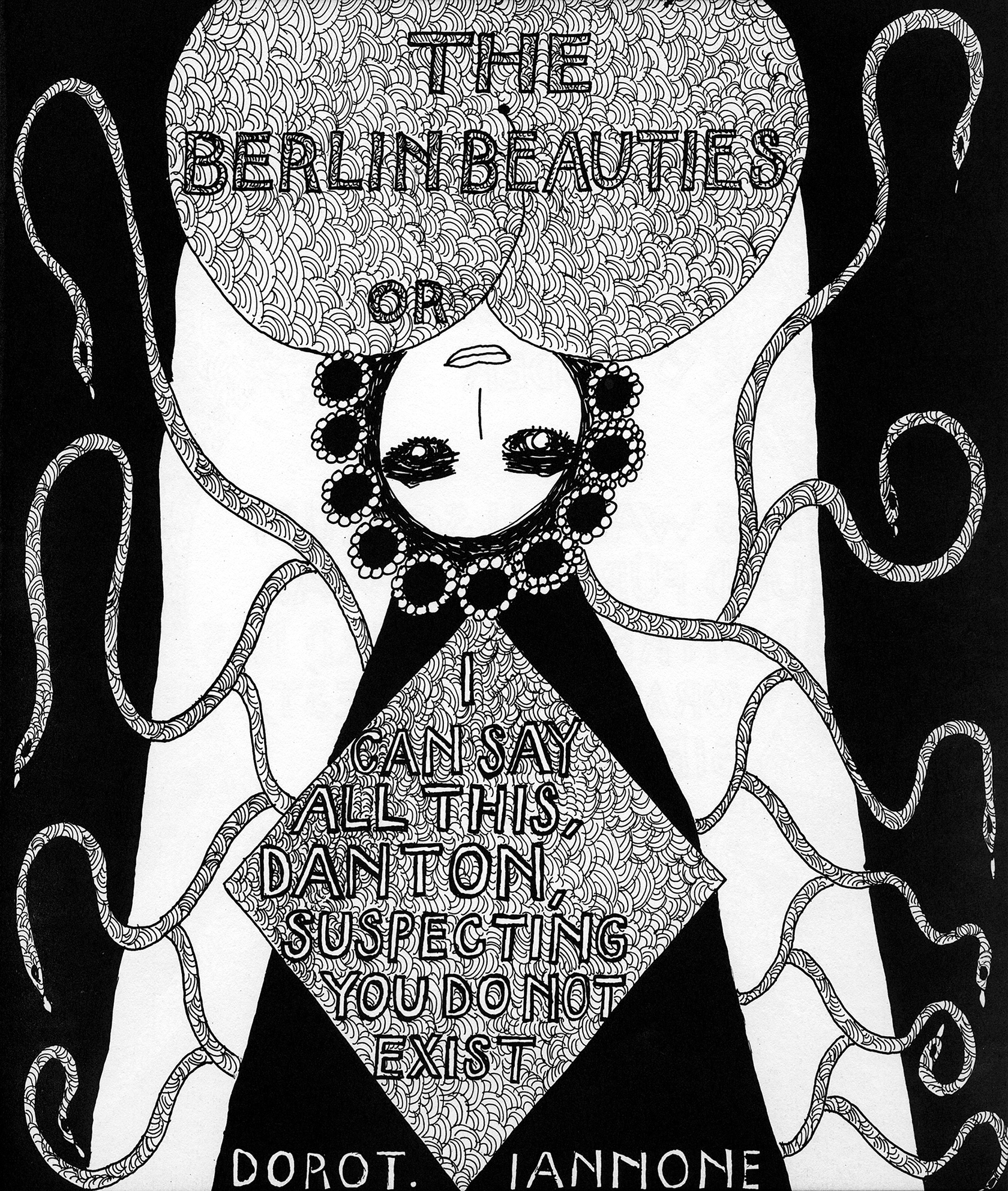

Which is not to say the book doesn’t contain variety. Pearson has a good eye for Iannone’s more oblique forms of self-narration and includes a diverse selection: lists, personalized tarot cards, recipes, a series of compliments and “uncompliments,” each with a germ of anecdote: “I love you because you almost gave me everything you had”; “You have a primeval vagina”; “Didn’t I scare the shit out of you when I told you I would try to become a better artist that you.”5 Iannone also writes poems, incantations, a dark fairy tale in the artist book Danger In Dusseldorf (1973) that picks up her life with Roth after her move to Reykjavik, recasting the couple as “Anna” and “Otto,” involved in a case of intrigue with the mysterious Hinter Soap family dynasty. The Berlin Beauties (1978), another artist book conjoining text and image with the addition of photography, is addressed to the fictional “Danton,” and takes the form of a series of riffs on its title using the conjunction “or,” continuously recasting itself, perpetually beginning, never resolving: “THE BERLIN BEAUTIES OR THE THING YOU FEAR AND DREAD, THAT WHICH WILL SAVE YOU AND FOR WHICH YOU WAIT, DOES NOT EXIST.”6 On one of its pages, Iannone depicts herself holding a paper divided by the words RADAR on top and LASER on the bottom. Radar, perhaps as in a means of perception, in this diagram is joined by the words “Heart/soul”; laser, perhaps as in a focused emission, by “Mind/Cunt.”

Dorothy Iannone, The Berlin Beauties (excerpt), 1978. Artist’s book, offset; 69 pages and cover, 8 × 9½ inches. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris.

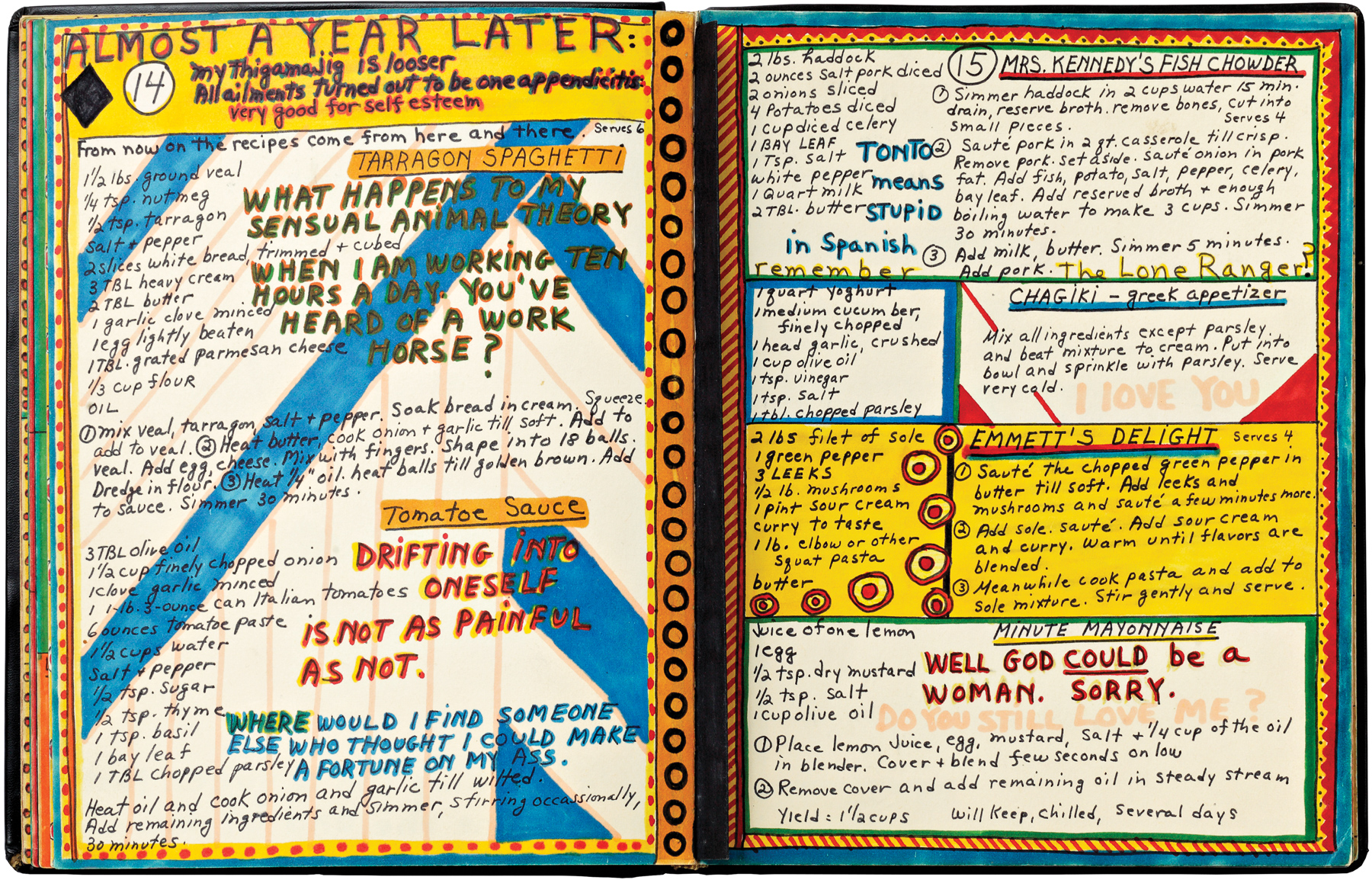

A Cookbook (1969), a collection of hand-written recipes with textual digressions, jokes, and aphorisms cut through, is another interesting case of oblique autobiography as well as a display of Iannone’s particular relationship to feminism. While she is clearly women-focused, “cunt”-focused, proclaims herself weary of patriarchy (in the etching, Lions for Dieter Rot The Present Lion Master, 1971, for instance) and by today’s standards appears rather explicitly feminist, she was not involved in the Feminist Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and her work has generally not found its way into contemporary, feminist-focused survey shows or histories. “I never considered myself a feminist,” she has said, “because I go my own way all the time.”7 One could imagine that part of her reticence might have also had to do with the fact that so much of what she made was in dialogue with men. Even the cookbook, which would seem an almost archetypal site for a feminist artwork, is prefaced with a message—one infers to Roth—that in part reads: “I NEVER WOULD HAVE STARTED THIS RECIPE BOOK IF I DIDN’T HAVE THE PLEASURE OF COOKING FOR YOU HERE AND THERE.”8 This comes after comparing him to God, who, Iannone, born a Catholic, writes, she knows is a man. Still, the work is dialectical. A few pages later, amidst a recipe for “Minute Mayonnaise,” she reconsiders: “WELL GOD COULD be a WOMAN. SORRY.”9

Dorothy Iannone, A Cookbook (excerpt), 1969. Artist’s book, felt pen on Bristol board; 69 pages and cover, 11¾ x 9½ inches. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul.

As a proponent of “ecstatic unity” and now as a practicing Tibetan Buddhist, Iannone’s spiritual leanings seem to direct her to a position of humanism more than anything else. Yet her work from the same period contends directly with the kind of feminism described by the critic Ellen Willis in 1977:

For me feminism meant confronting men and male power and demanding that women be free to be themselves everywhere, not just in a voluntary ghetto. Separatists argued that a consistent feminist had to break all sexual and emotional ties with men, yet it seemed to me that not to need men for sex or love could as easily blunt one’s rage and pain and therefore one’s militance; I also had the feeling that there was a lot of denial floating around the separatist community—denial that breaking with men did not solve everything, that even between women love had its inescapable problems.10

Iannone is now in her eighties and has lived in Berlin since 1976. Only in the last decade or so has she become recognized in the United States. She appeared in the 2006 Whitney Biennial and received her first American retrospective in 2009 at the New Museum. In the end, she might agree that love has its own “inescapable problems.” Her later work in this book moves away from equating erotic love with divinity, instead finding that great union or yoking within oneself. “I began to look for you in my own heart,” reads a line of text from her painting My Caravan (Or) Going On With The Journey Towards Ultimate Union (1990). The cynic might say, anyone could have told you as much. But in the same instance, in a secular-based culture of contemporary art, how transgressive to have once believed anything else.

Kate Wolf is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles.