Introduction by Chon A. Noriega

DOWNTOWN L.A. (7th and Broadway)

A man who wears his hands backwards is selling newspapers. No one buys but I take a closer look at the explicit cover of a sensationalist Mexican magazine that gives weekly pictorial accounts of homicides, suicides, mutations, mutilations, and a column for the who’s who in vital statistics.

“You buying?”

“No, just looking.”

There it was lying naked, severed neatly between two railroad tracks; someone else’s ass. It was a frightening three-quarter-page photograph. In Guadalajara, Jalisco, someone had crossed the path of a speeding night train only to land butt first into a position of prestige: the front page.

“If you’re not buying, why’re you looking so hard?”

“I was wondering whose ass that might be.”

“It’ll be yours if you don’t get the hell away from my stand.”

The newspaper vendor waves good-bye, maybe he’s calling me back.

–Harry Gamboa Jr., “Phobia Friend,” 1977

In “Phobia Friend,” a short story by Harry Gamboa Jr., the narrator is looking at a Mexican tabloid, most likely ¡Alarma!.1 The narrator, the “I” of the narrative, is the unnamed Chicano flaneur that appears in other Gamboa stories. He wanders the streets, describing the absurd and random events that happen around him. He attempts to maintain a critical and safe distance, creating a cognitive map by which to understand and navigate the modern and segregated city, only to learn that he has been looking at himself. For Walter Benjamin, the flaneur is equivalent to the writer or the photographer who “goes to the marketplace, supposedly to take a look at it, but already in reality to find a buyer.”2 In contrast, Gamboa’s flaneur is looking, but is neither seeking a buyer (for his aesthetic observations) nor buying (in a consumer culture). He is not, and cannot be, the detached observer whose presence merely reinforces the boundary between producers and consumers. His class status does not afford the illusion of standing outside the mise en abyme. of modernity. His ass is on the line….

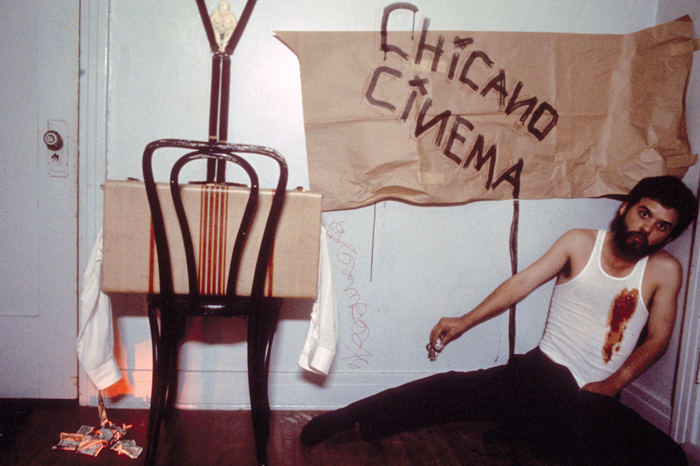

Harry Gamboa Jr., Chicano Cinema, 1976. Pictured: Harry Gamboa Jr. © 1976, Harry Gamboa Jr.

First published in 1963, ¡Alarma! provided a way for Gamboa and other Chicano artists who came of age in the 1960s to understand the “contact zone” within which they lived.3 The Mexican tabloid corresponded to their parents’ linguistic, narrative, and cultural framework, while its sensationalism resonated with the American TV culture, from which Mexican-American children were missing, but that often served as their babysitter. Indeed, the photographic imagery in ¡Alarma! depicted the life-and-death stakes of modern urban life with a Mexican face. It also provided an unusual corollary to the concurrent and gruesome TV news coverage of the Vietnam War—a war in which Chicanos were over-present on the front lines and yet under-represented in the media—a dynamic that played out with deadly force at the Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War on August 29, 1970, in what many called a “police riot.”4 This event constituted a point-of-origin for contrasting approaches to the art of social protest: a “Chicano cinema” working in a realist tradition and aimed at a mass audience; and a Chicano conceptualism that turned to the “cinematic” in order to critique the constructed nature of visible evidence and its publics.5

Harry Gamboa Jr., L.A. County Deputy Sheriffs in East L.A., 1972. © 1972, Harry Gamboa Jr.

Gamboa’s chance encounter during the Moratorium with Francisca Flores, a civil rights activist since the 1940s, would lead to the formation of the conceptual art group Asco with Gronk, Willie Herron III, and Patssi Valdez. Much scholarship has been written about Asco in the last fifteen years, but one point bears repeating: “What one notices most about this body of work (and subsequent staged performances and conceptual video) is the unrelenting expression of violence outside melodramatic and moral discourses—as a cultural logic, an administrative tactic, a familial ritual, and a fact of everyday life.”6 The work draws from the spectacle of U.S. and Mexican mass culture, at the same time hovering between their somewhat different views about death and violence. In the United States, the dead are resurrected as celebrity zombies: Elvis is sighted in a Safeway grocery store, J.F.K.’s brain continues to lead our nation from an underground bunker. In Mexico, the dead are celebrated—or observed—for being dead: it is the fascination of “someone else’s ass” leaving the public stage, and the inevitable acknowledgment that it is also your own. Here is a contact zone, not just for cultural conflict, but also for a politics grounded in the memento mori rather than on resurrection.

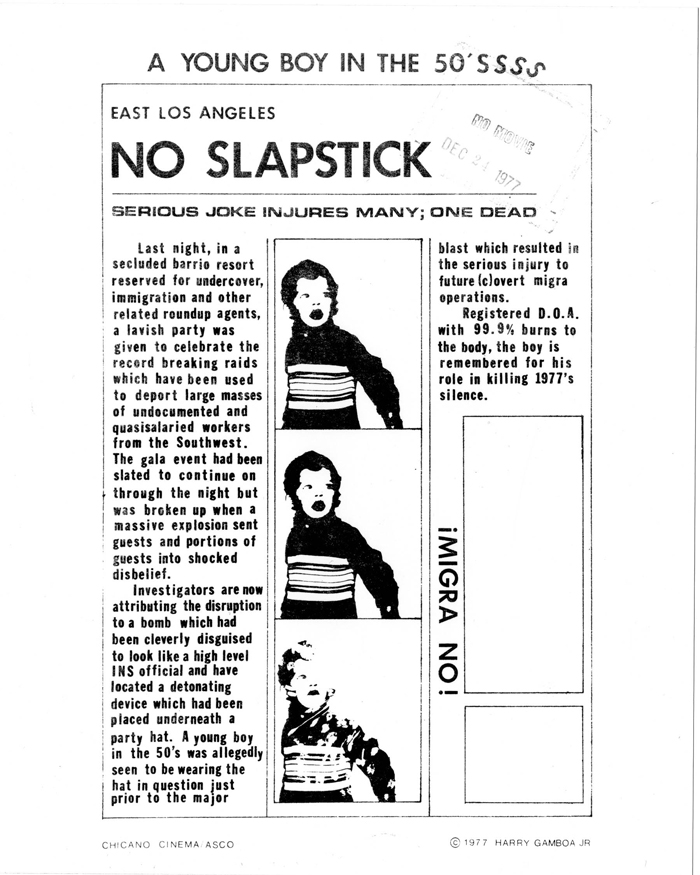

Harry Gamboa Jr., No Slapstick, 1977. © 1977 Harry Gamboa Jr.

If Gamboa’s fiction engages the autobiographical “I” in order to present a subaltern flaneur and a corresponding artistic practice and cultural politics (along the lines of Fredric Jameson’s “aesthetics of cognitive mapping”7, his photography and video cast a conceptual “eye” on Chicanos as a social group of “modern fugitives” within Los Angeles.8 Since 2005, Gamboa has worked with his ensemble performance troupe Virtual Verite in order to produce urban narratives in photography, video, and, to a lesser extent, live performance and audio. Each work involves an observer, modeled on United Nations observers, that witnesses the unscripted, staged events and their impact within the urban environment. The observer is at once an actual witness to the events and a conceptual conceit within Gamboa’s visual and audio documentation: Here, experience is placed above evidence, yet it resides within a body that is not required to speak. In Civillains (2012), Gamboa returns to the contact zone, this time as it is played out within citizenship itself, which he articulates through a pun for “civilian” that overlays “civil” and “villains.”9 For Gamboa, the increasing militarization and criminalization of public space—and not just in such racialized spaces as East L.A.—produces a situation in which the civilian is re-figured as a villain or enemy of the state. Civillains is part of a fotonovela series called Aztlangst. The series title combines the sense of a mythical place of origin (Aztlan) with the dread and self-awareness experienced by the dispossessed in the present moment (angst). As in Gamboa’s other fotonovelas, the performers’ expository statements function as a Greek chorus for an implied dramatic narrative taking place somewhere else (homeland) among other unnamed social actors (civilians). Like “Phobia Friend,” wherein the narrator finds himself at once in Guadalajara and Los Angeles, looking at someone else’s ass and his own, Civillains collapses social spaces, temporalities, and perspectives—the here and now of the civillain, and the somewhere else of the would-be civilian—onto the surfaces of an alienating urban scene. What haunts the image is the thin white ribbon that connects the performers to each other as they navigate, or “occupy,” public space, as they speak, with impersonal precision and abstracted affect, their anguished, hopeful path toward participation in a civil society.

Chon A. Noriega is a professor in the UCLA Department of Film, Television, and Digital Media and Director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. As part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980 initiative, he organized and co-curated L.A. Xicano, four interrelated exhibitions on Chicano art at the Autry National Center, Fowler Museum at UCLA, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art between October 2011 and February 2012.

Since 1972, Harry Gamboa Jr. has been actively creating works in various media/forms that document and interpret the contemporary urban Chicano experience. He cofounded Asco (Spanish for nausea) (1972-87), the East L.A. conceptual performance art group. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and featured in numerous publications. He is a member of the faculty at California Institute of the Arts, School of Art, Program in Photography and Media. www.harrygamboajr.com