The first representation, according to the Bible, was affirmed by its appearance—God looked at the man He made in His own image, and said it was “very good.”1 The first subject was thus an object, subject to an objective standard of being. This looping fusion of subject and object is also the animus of art, an animating spirit that Adorno said was “bound up with, performed, and mediated by,” all artwork.2 As animus is one definition of genius, Gillian Wearing’s Pin-Ups project is genius.

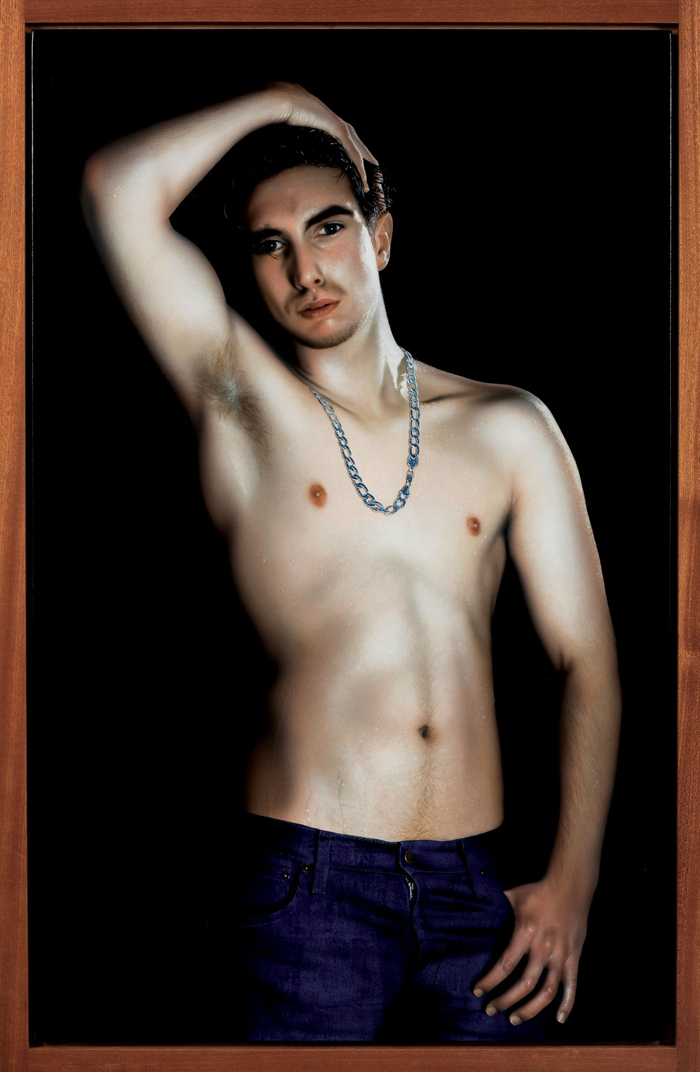

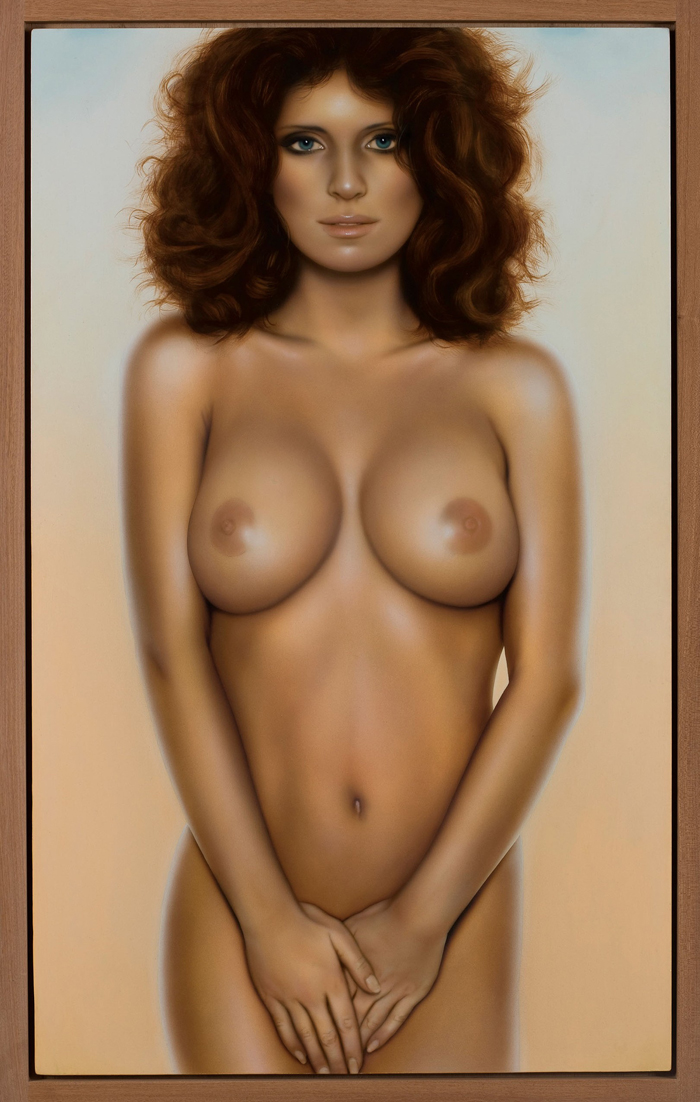

The project features seven paintings framed in pale wood. The paintings are kitsch, glamour portraits of pin-up subjects based on Photoshopped photographs. Each frame proves to be a box, opened with white cotton gloves to reveal a handwritten letter and several small, snapshot self-portraits of the person painted. The project began when Wearing posted an online call for people to apply to become a glamour model. From these written applications, Wearing selected individuals to be auditioned. In the audition, Wearing explained the project and probed the applicant’s interest, looking for those “who were enthusiastic, who had real aspirations.” She picked five women and two men, who then worked with science-fiction-book-cover artist Jim Burns to create the final look of their portraits. Wearing has said that she wanted to create paintings, not photos, images, or illustrations, because “with painting there is a seductiveness that enhances the transformations of the models.” She also wanted the paintings airbrushed and done in acrylic “as it has a more Photoshopped look.” Paradoxically, she notes: “The realism of the final image was important.”3

The genius of Pin-Ups is that there is no contradiction—the project is a perfect argument. There is the art object, whose subject is an objectified image of itself as subject. There is the subject, whose object is a subjectified image of itself as object. The subject is literally contextualized by his/her handwritten application to Wearing; the object literally objectified by the fabrication of an image, not an illustration. Illustration denotes, image connotes. In 1964, when Barthes wrote his pivotal essay that differentiated between connotation and denotation, photographs were considered representational, paintings illusionary. Barthes was arguing for reading photos critically, a critical chore we now take for granted. In the age of Photoshop, photos contain arguably less truth-quotient than paintings, and paintings have arguably more validity by way of overt artifice—a painting is a painting. Thus, the photo acts as an illustration, denoting the properties of the thing represented, while a painted image has multiple connotations, including the literary. In Wearing’s project, the original snapshots are illustrations of the subject’s cellulite-rich and canker-sored self. The final paintings are subjectively and objectively perfected images of a firm, unblemished “itself,” just as man made God in his own airbrushed image. This new subject/object, this “sobject,” is man’s own imago: the man created of man by man. God is dead, but we have Wearing.

In this sense, Pin-Ups is Wearing’s post-Lacanian answer to the Freudian riposte of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915-23). Duchamp’s box was glass, his bride and her bachelors tinny tinker-toys, frozen in frustration of the many men for the one true Woman. Wearing’s men and women are fully realized because they are fully fantasized: they contain their own happy self-recognition, fulfilling that desire which is itself the cause of desire. The promise and problem of a century’s worth of conceptual art is here in a nutshell: whether it is nobler to suffer the nothing than to not suffer suffering at all. Duchamp allegorically mechanized desire’s grinding and thwarted appetites, including the cracked box they came in; Wearing falsifies flesh as flesh is really falsified—plumped and plucked and Photoshopped, primped for the short sale. There is no body that cannot be altered for commodification, and no body that cannot be commodified.4 Duchamp’s Snow White bride was a wanker’s nightmare and delight; Wearing’s imagos are denuded semi-nudes, erotic as a Bacardi ad. The only boner here is a self-reflective joke, the gag of the self-made man.

With one exception, each of the applications written by Gillian’s sobjects attests to a radical mind-body makeover, for example the fat girl gains confidence and loses weight and the oddball boy realizes that weird is wonderful. Their stories are tales of private and public humiliations (the boy whose “sexy” snaps were plastered all over school by the girl he loved; the fat girl whose shame triggered epileptic fits), writ small and banal and terrible in their tiny tortures. Salvation comes by way of equally public redemption: to “prove everyone that I ‘can’ look sexy and pass as a model!” (Dominik, 2008). Or, simply: “to be envied by others.” (Anne-Marie, 2008)

Literary critic Sianne Ngai has noted that “it is through envy that a subject asserts the goodness and desirability of precisely that which he or she does not have, and explicitly at the cost of surrendering any claim to moral high-mindedness or superiority.”5 In his 1972 book Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes about glamour: “Publicity [advertising] is never a celebration of a pleasure-in-itself. Publicity is always about the future buyer. It offers him an image of himself made glamorous by the product or opportunity it is trying to sell. The image then makes him envious of himself as he might be. Yet what makes this self-which-he-might-be enviable? The envy of others. Publicity is about social relations, not objects. Its promise is not of pleasure, but of happiness: happiness as judged from the outside by others. The happiness of being envied is glamour.”6 But Wearing’s glamorous sobjects have incorporated the projected envy of others into an even deeper happiness: the envy of oneself by oneself. In Pin-Ups, the sobject articulates the desirability of that which it now possesses, confirming that the experience of the objective world is also a universally subjective characteristic. It is important here that the sobject speak, because it is this tendering of self as self-made that plugs the gap between what is imagined and what is real. Unlike the Freudian folly that Duchamp put under glass, there is no longer any sublimation of desire once desire has been directly inscribed in the Self as Thing As it turns out, in response to Freud’s query “What do women want?,” “what” is what women (and men) want.7 It is also important that this speech be handwritten, signaling how language will be written into a picture that has been itself rewritten. Rewritten into a photo that has been turned into a painting that looks Photoshopped. The one false note in Wearing’s project is the fact that the letters and snapshots are inside the box and the imago is on the outside. But there is no inside and outside, simply a hinge, the shutter that snaps open and closed. To be envied by oneself as an other, and as a self by others—to become that which is desired by way of desire and to live to tell the tale—is our post-Lacanian wet dream.

The arguments I’ve gotten into over this exhibit are disagreements about exploitation and objectification, about gender and class, false consciousness and the artificial “I.” These fights prove and reprove the argumentative genius of Pin-Ups, as the work consistently defers resolution, posing instead another point of contention. There is no escaping the loop. For every argument that Wearing exploited the small dreams of small people, there is the counterargument that the models were full agents in their representation, and thereby existentially realized to an unblemished fault. The choice of a science-fiction-bookcover artist is another bit of brilliance in this regard, as the genre invokes a cerebral sort of popular fantasy, a thinking-man’s romance with romance. For every gallery-goer who would sneer at the pitiable yearn to become a pin-up, there’s Rowena, the formerly fat epileptic, painted lying on her now-thin and lingerie’d back, who says, “I still have issues with my body, but don’t we all?” Or Ziyona’s liberating, “I’ve always been portrayed as a good girl & I want to rebel a little.” And Anne-Marie’s plain-wrap truth, “I pictured myself.”

The archival inclusion of the snapshots taken by the subjects of themselves underscores this self-imaging, emphasized most directly in Ziyona (2008), where the University-educated model (“don’t you think in today’s society were [sic] fabricated through illusions of how a woman should look”) is engrossed in posing for her cell phone camera. It’s Narcissus, but Narcissus with Echo crooning sweetly below the reflective surface. It isn’t that fantasy and reality are “inextricably entwined,” as Wearing has described, but that image is gladly enfleshed in the dual materiality of paint and text.8 The pale frames serve as pine coffins for the immanent self, and the viewer/reader is the vehicle for the sobject’s tendered transcendence.

The second body of work is Wearing’s Family History (2006), a commissioned film installation based on a 1974 BBC documentary, The Family, itself based on the PBS show, An American Family (1973). Wearing’s first piece is a video featuring two sets, made to look like a split screen.9 On the left, a child playing Wearing at the age of ten sits in her family’s reconstructed beige-and-taupe living room, watching The Family. On the television, 19-year-old Heather Wilkins is being encouraged to stay in school by a career counselor. On the right, the now middle-aged Wilkins is interviewed by popular BBC talk show host Trisha Goddard in a boldly colored faux TV studio. (A large-screen version of the staged Goddard-Wilkins interview plays in another gallery room.) They talk about the television show, about events that happened on camera, including the career counseling scene (Wilkins was infuriated by what she felt was classist condescension), and about how having been on the show continued to affect the lives of family members. Again, subject becomes object becomes sobject. The frame of the set, like the frame of the television and the frame of the painting,10 is the box in which we come into our being.

In Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape (1958), the constipated Krapp spends his ungentle decline eating bananas and reviewing his masterwork: boxes of self-made audiotapes, narrations of his life, from childhood to the interminable today. Directing the play in 1977, Beckett explained, “[Krapp] escapes from the trap of the other only to be trapped in self.”11 As he drops banana peels to the floor, Krapp dreams of artistic glory, foreshadowing his inevitable Icarustic pratfall. Wearing is not so ironic, for there is nothing outside the box that contains the history and image of us. Pin-Ups is prefaced by a large black and white photo of Wearing by Wearing, titled “Me as Arbus” (2008). In his discussion of representation, Adorno wrote that as much as art has meaning, art “is endowed with sadness,” and the more successful the invocation of meaning, the sadder the art. Tristesse is “heightened by the feeling of ‘Oh, were it only so.’”12 In this work, it is so. As Wearing shows us and herself, to be not is also to be. For as genius would have it, “I” am the Lord our God.

Vanessa Place is a writer and lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press.