Georganne Deen, Super Mirror (detail), 1996. Oil and collage on linen 72” x 108 inches. Collection of Tom Patchett.

The paintings of Georganne Deen collectively present the narrative of a young American girl becoming a woman in the second half of the 20th century. The privileged figures in this tale are a family group headed by a “bitch mother” whose only nurturing consists in throwing a spotlight on the rivalry between her offspring—the artist and her sister—and an absent father, who is mostly represented by visual synecdoches, as in 1995’s The Divine Anti-Comedy where an oil field acts as his stand-in.1 Like the tale of Christ, Deen’s narrative represents both the life-story of one unique individual and a psycho-socially embodied “myth” that many of us either act out ourselves—consciously or unconsciously—or use to help make sense of others.

Thru the Super Mirror (1996) is typical of Deen’s work. A wide-angled, black and white image yellowed with age, like a still from a ‘50s melodrama, depicts a typical girls’ bedroom—two single beds with frilled covers, with a nightstand and lamp in between. Don’t be fooled; this is a war room, the chamber where a horrid battle was fought. Laid over the surface of this quasi-photographic image, as if a child were working on it, are a series of cutouts, scribbles, painted objects, and writings. The cutouts, of eyes from women’s magazines, are arranged in two vertical columns framing what is presumably the future artist’s bed. Between these all-seeing protrusions in the surface, chains of pearls and other decorative doodles weave a protective net, not unlike an Inuit spirit-catcher. At the modal point of this figure where it holds together, Deen has painted a large pop-art flower. Falling from its petals are three pairs of drops. Though they too at first look like pearls, the painted lines actually form the words “no no no no no no.” “This multi-layered creation represents my guardian spirit/friend/psychic-mother (possibly a higher form of consciousness I chose to make into another being) whom I believed to be my real mother, and always referred to her as such. This was one of the great sources of conflict with my sister who thought I was making the whole thing up.”2

On the far side of the room, in front of the sister’s bed, in the center of a painted paper doily, stands the artist herself, hastily scribbled in the guise of a Victorian nursery rhyme morality figure, the one who never, ever brushes her hair or files her nails. Needless to say, she will come to a bad end. Above the child’s head a thought-bubble presents a young woman shooting up, all by herself. Between her and the all-seeing, pearl- weeping, flower-headed guardian, a coffee stain soils the image. Above and below, a poem scurries across the surface:

Above: I taste acid, angel dust + speed. I’m driven by greed. I’m gutless + horny.

Below: Shhhhh…Breathe…exhale a spring collection of butterflies heading for Aruanda where nobody worries, hurries or begs. Light upon a dinner plate dahlia… you never have to work again. Go ahead + gush some snap dragons + unicorns. Tune into some kettle drums by Shiaparelli. You’re springing eternal. You’re the heart of a new god.

Painted over the lower portion of this text is a label reading, “PARIS NEW YORK,” emblem of covetous desire, like a high fashion ad.

Elaborate, allegorical, decorative and highly figurative, Deen’s work is sometimes seen as too self-expressive (read: narcissistic, uncritical, indulgent and feminine) to be taken seriously as contemporary art. In anticipation of the upcoming “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution,” exhibition at MOCA, I would like to argue that self- exploration—when undertaken, as does Deen, with a ruthless critical eye—is a profoundly important and necessary activity.

In Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, one of modern literature’s seminal texts, the protagonist is trapped by his inability to live up to the Romantic ideals to which he aspires.3 (The term “romantic” is used in its literal sense, as the ideal derived from reading Romances, i.e., novels.) Though this underground man is in no sense a hero—he is a sniveling chaotic contradictory being whose only interest is in the vibrations of his own hypersensitive nerves—Dostoyevsky’s approach to his portrayal is one of the most admired and emulated strategies in all of modern literature. Dostoyevsky’s unflinching honesty about the abject realities of the modern subject is mind-blowing and helps us all to better face up to the truth about ourselves. But while modern literature has been dominated by exploration of the abject self—Dostoyevsky, Samuel Beckett, Elfriede Jelinek—with the exception of certain “expressive” moments, examination of the personal self is seen as anathema in certain parts of the visual arts world. Indeed, overt self-exploration, especially in a figurative style, is often seen as the opposite of art, that is, as kitsch. And when personal emotion has been allowed, it is often as raw, gestural outpourings signifying verbally inexpressible rage, rather than in a figurative form that may be used as a tool for a critically distanced self-examination. Mary Kelly’s Post Partum Document is interesting in this context, for it is both non-figurative and ruthlessly self-exploratory.

Georganne Deen, Super Mirror, 1996. Oil and collage on linen, 72 x 108 inches.

Collection of Tom Patchett.

Just as some strands of Modern Art have aimed to distinguish themselves from non- art by privileging form, i.e., the parameters of their medium — flatness, surface, paint-on- canvas — over illusion and figuration , some art has sought its contemporary identity in a rejection of the authorial subject. This can be done in many ways, such as by using found materials, mechanical methods of production, and documentary techniques borrowed from the museum and archive. Another way is to keep the style figurative, but to reject personal memoir in favor of such topics as the politics of the art world or some other social sphere.

Perhaps one reason for this rejection of the confessional mode is its ubiquity in contemporary life. Though this mode of expression might seem to arise from the emphasis placed on individuality in “free” societies, according to the social theorist Michel Foucault, it is nothing but the effect of a specifically modern form of power that enslaves us precisely by demanding that we reveal (to It?) our innermost secrets.4 This demand, which manifests in psychiatry, opinion polls, and chat shows, as well as literature and film, is a unique feature of western culture, and shows that while God may be dead, Catholic practice is not. Some anti-subjective, anti-expressive and anti-confessional art is an understandable rejection of this demand, a reaction against this particular form of power. However, we should be careful not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. On the one hand, the confessional is still a place where tremendous power resides, albeit now located in the box in the living room, not the one in the church. On the other, examining oneself honestly has long been regarded as the hallmark of an “enlightened” but humble humanity. According to Foucault, the specifically bourgeois form of power does not oppose or repress pleasure — it positively feeds off it. Following Foucault, Slavoj Zizek has argued that the principal command in the (post)modern world is not “thou shalt not,” but “thou must.” “Have a nice day,” is not a profession of hope, but an order. “You will enjoy yourself, whether you like it or not.” Watch American television, especially the ads, and it is hard to deny the logic of this argument. The command to enjoy is an invasion of privacy that actually evacuates the self, turning people into mindless automata. Disneyland, where people enjoy themselves, no matter what, is the epitome of this operation, and the idea that this might become the model for all society is deeply problematic.

However, bourgeois power works not just by commanding (mindless) enjoyment. To function, it must extract our pleasure from us, and it does this by coupling pleasure with guilt, then making us unload that guilt by talking about it. In Foucault’s words, discourses about pleasure are ways of turning pleasure itself into a form of social capital that can be accumulated. From this perspective, no form of self-confession can possibly be considered “transgressive;” all revelation, no matter how shocking, is just another sop to the machine, whether it comes from Oprah or de Sade. The anti-confessional attitude of contemporary visual art is one of the few ways to circumvent the (bourgeois) power game when it is viewed from this Foucauldian perspective. But there is more to this matter than meets the eye. For just as Foucault can argue that the guilty pleasure of spilling all about one’s joy is the essence of modern subjectivity, many other thinkers, including Dostoyevsky, claim that the core of the (post)modern subject is not joy, but paranoia. For such thinkers, the desire to “tell” is not so much driven by the needs of a Capital conceived as a pleasure-sucking machine, but rather by the subject’s horribly self-enclosed fascination with its own relationship to fear and inadequacy.

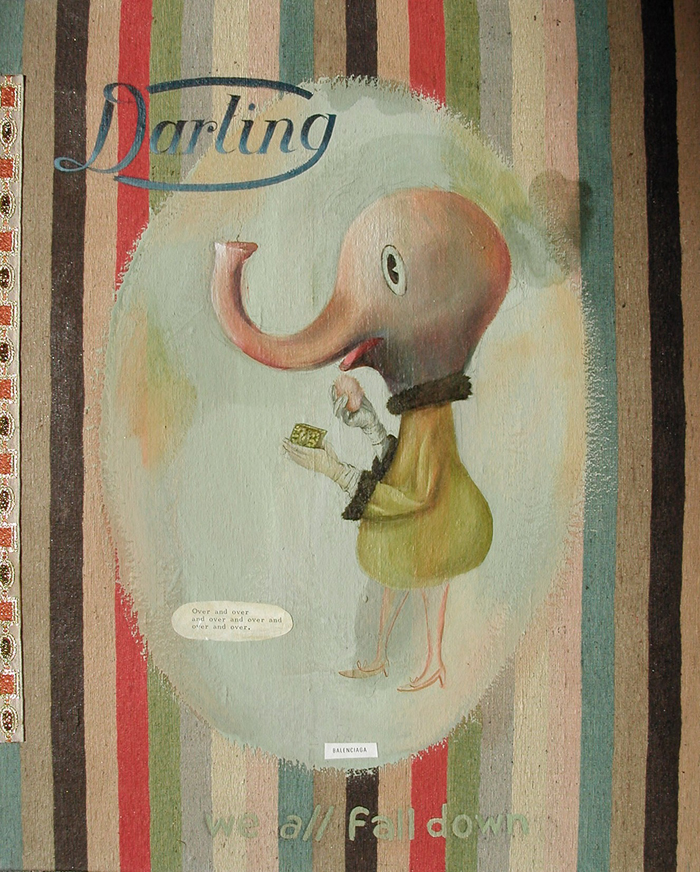

Georganne Deen, Darling, 1995. Oil on silk, 20 x 16 inches. Private collection.

What has been called paranoid knowledge is widely seen as one of the major epistemes of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In a slew of works, from Fredric Jameson’s The Geopolitical Aesthetic to Timothy Melley’s Empire of Conspiracy, paranoia is conceived as the affective force behind a new kind of epistemology, and a new kind of thinking- being. This conspiratorial slant in the contemporary imagination owes its existence to modern man’s perception that his inability to grasp the totality of relations within which he is enmeshed makes him a failure. Of course, the notions of both a totality and the system are persecutory abstractions, arising not from man’s inability to (mentally and imaginatively) master his environment, but from his unwillingness to acknowledge that totality itself is a conceptual tool that may help in the struggle towards a different society—an ideal—not an objective fact of the external world.

The paranoid and quintessentially (post)modern subject is seen, by Jameson and others, as most powerfully embodied in the figure of the conspiracy theorist—a belated, redundant persona who is subject to a seemingly impossible array of coincidences. The literary critic and feminist Sianne Ngai argues that this figure only represents the perspective of dominant subjects, subjects habituated to mastery.5 For these people the loss of (total) control comes as a shock, causing a traumatic reversal in their perception of the subject-world relation. From being the controllers (if only in their imaginations) of the (post)modern world, dominant subjects suddenly experience themselves as totally controlled. As Ngai points out, such subjects only see the totality of the system as if from the outside, failing to recognize their own complicity within it, hence their sense of persecution, the sense that their own subjectivity and desires are being squeezed out.

On the other hand, Ngai suggests, having never felt the omnipotence of mastery, subordinate and minority subjects, including women, have quite a different experience of (post)modern trauma. Though such subjects also feel persecuted and paranoid, in their case, the persecutory agent is not seen as entirely external, but is experienced as partially internal. In other words, unlike dominant subjects, subordinate subjects do not project all responsibility for the sense of oppression onto some amorphous persecutory Other, but acknowledge their own complicity in the constraint. (Indeed, the partial internalization of responsibility for an oppressive situation may be the defining quality of subordinate subjectivity.) This sense of one’s own complicity in the (post)modern “system” is the “unnamed component” that pushes the subject beyond a simple state of persecution, into a more paradoxical state where she is simultaneously both the oppressed and the oppressor—the object and the agent of persecution. Ngai argues that this paradoxical state with its characteristic excess of affect opens a space for subordinate subjects to develop a different relation to fear, and another kind of paranoid knowledge. An acknowledgement of her own complicity in a world that repels her is what makes Georganne Deen’s self-exploratory artwork of such fundamental significance today.

Georganne Deen, A Great Wounding, 2005. Oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches. Collection Tom Patchett.

Though Deen’s paintings constitute a rigorous self-analysis, they do not conclude that all the bad comes from others—siblings, parents, or “society.” Quite the opposite, the heroine, the good- bad-lovely-dangerous-intoxicant is none other than little Georganne herself. “The painting [Thru the Super Mirror] depicts the psychic battle that took place between my psychic mother’s (the spirit figure–author) attempts to calm me down, and me, as I grew meaner and more self-destructive (hateful side versus the kind compassionate loving side of me that wanted to believe I was good). The poem explains the two sides of myself at war.”6 The trauma discovered here is not so much the affect of a battle between self and others as the outcome of a struggle between two opposing sides of the artist’s self. “As if navigating between Scylla and Charybdis, the drug-fractured consciousness of the adolescent vacillates between the reality given at the top of the painting–‘I taste acid…[etc.]’–and the fantasy played across the bottom–‘Go ahead + gush some snap dragons + unicorns…’”7 What Deen articulates through her work, what is so difficult for her, and so difficult for us, if we truly confront it, is that she is not merely the victim of her circumstances, but is also their perpetuator; she herself is complicit in her misery. As Monk so pertinently asks in his catalog essay for Deen’s solo exhibition at the Powerplant, “Who says that teenage consciousness cannot partake of the same splendor and excess of destructive impulses [as Delacroix]?”8 Confronting this duplicity in oneself, and working through, or with it, is I believe crucial to changing our world, both personally and politically. And for me, the paintings of Georganne Deen offer an inspiring example of how we might go about it.

Christine Wertheim writes poetics and aesthetic criticism. Her book +|’me’S-pace, will be published in 2007 by Les Figues Press. Other work has appeared in La Petite Zine, Five Fingers Review, Cabinet, Open Letter, Art History vs Aesthetics, and X-TRA. She co-organizes an annual writing conference whose publications are Séance (2006) and The Noulipian Analects (2007), and co-directs The Institute For Figuring, www.theiff.org. She teaches in the school of Critical Studies at CalArts.